Introduction: Setting the Stage and Roadmap of the Article

Throughout human history, ideas and ideologies have shaped the course of political systems and international relations. Every era has witnessed the rise of philosophies born from its unique struggles, conflicts, and aspirations. Among the most influential of these are Realism and Liberalism — two contrasting yet complementary schools of thought that continue to define the global political landscape today.

Realism is grounded in the belief that the world operates in a state of anarchy where power, security, and self-interest dominate. It argues that states act primarily to ensure their survival and enhance their strength, often at the expense of cooperation or morality. In contrast, Liberalism challenges this pessimistic worldview. It emphasizes the potential for peace, progress, and cooperation through dialogue, institutions, and shared values. Where Realism focuses on power, Liberalism focuses on principles.

In the modern world — marked by climate change, economic inequality, technological rivalry, and geopolitical tension — the balance between these two ideas has become more crucial than ever. Nations today face a constant dilemma: should they adopt a realist approach to safeguard their interests, or a liberal one to foster cooperation and long-term stability? The answer is neither simple nor absolute; it lies in understanding when and how to apply each philosophy effectively.

This article aims to explore the philosophical foundations, historical evolution, and major proponents of both Realism and Liberalism. It will then examine their influence on contemporary politics and international relations, highlighting real-world examples that demonstrate how these ideas manifest in global decision-making. Finally, through personal reflections and lived experiences, the article will attempt to answer a deeper question — how can individuals and societies balance idealism with practicality in today’s complex world?

If you are a student of politics, international relations, or simply someone curious about how ideas shape our world, this piece will serve as both a guide and a reflection. It is not merely a theoretical discussion but a journey into understanding how Realism and Liberalism coexist, clash, and complement each other — and what lessons we can draw from them in our personal and collective lives.

Why This Discussion Matters

In today’s world, where nations are deeply engaged in safeguarding their borders, security, and strategic interests, global challenges such as climate change, human rights crises, and economic inequality demand collective action. This raises a crucial question — should the world continue to follow the power-centric path of Realism or embrace the cooperation and ethical values of Liberalism?

This discussion extends far beyond international politics; it resonates with our personal lives as well. Each day, we face choices between being practical or staying true to our ideals. Understanding the balance between Realism and Liberalism, therefore, is not just a theoretical exercise — it is a reflection of human nature, ethical reasoning, and the constant search for harmony between self-interest and collective good.

Realism: Core Ideas, History, and Major Thinkers

Realism is one of the most influential schools of thought in political science and international relations. Its core premise is that human nature is inherently self-interested, and power is the central force driving politics. Realists believe that the international system is anarchic — meaning there is no central authority to govern or enforce rules among states. In such a world, every nation’s primary goal is to ensure its security and national interest.

Realism argues that morality and idealism play a limited role in politics, as decisions are ultimately driven by the balance of power and self-interest. States are viewed as rational actors that act strategically to survive and protect their sovereignty in an uncertain global environment.

The roots of Realism can be traced back to the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, who, in his account of the Peloponnesian War, emphasized that human conflict arises from fear, honor, and self-interest. Later, Niccolò Machiavelli, in his seminal work The Prince, asserted that political success depends on pragmatism and outcomes rather than moral intentions. In the 17th century, Thomas Hobbes in his work Leviathan described the state of nature as “a war of all against all,” arguing that only a powerful authority can maintain order.

In the 20th century, Realism was redefined by thinkers like Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. Morgenthau developed the idea of “Political Realism,” emphasizing power as the main currency of international relations. Waltz later advanced the theory of Structural Realism or Neorealism, suggesting that the behavior of states is shaped more by the structure of the international system than by individual leaders’ intentions.

Thus, Realism is not merely a theory but a pragmatic worldview that explains why nations often prioritize competition over cooperation and why “power” remains the central element of global politics even today.

English/European Perspective

The emergence and evolution of Realism are deeply rooted in the European historical context, shaped by centuries of wars, imperial ambitions, and the constant struggle for power. From the 17th to the 19th century, nations like England, France, and Germany practiced power politics, where maintaining a Balance of Power became essential to prevent any single nation from dominating Europe.

British thinkers and diplomats refined this principle into a guiding doctrine for international stability. The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) — which ended the Thirty Years’ War — marked the birth of the modern nation-state system, enshrining the concept of sovereignty and non-interference. This treaty became a cornerstone of Realist political thought, asserting that states are independent and must rely on their own power to survive.

Throughout European history, the Realist mindset prevailed — moral or religious ideals were often set aside in favor of pragmatic decision-making. Power, not virtue, became the measure of success. This perspective laid the intellectual foundation for modern diplomacy, geopolitics, and international security policies that still dominate global relations today.

Practical Examples (Wars and Power Politics)

Several historical events demonstrate the practical application of Realist principles. The Second World War is a prime example — nations acted according to their security interests rather than moral concerns. Britain and France initially pursued appeasement with Germany to maintain peace, but when Hitler’s power grew uncontrollable, they were forced into war — a clear reflection of the Balance of Power principle.

The Cold War further solidified Realism’s dominance. The rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union was not merely ideological but rooted in the pursuit of global influence and security. The nuclear arms race, formation of alliances such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and numerous proxy wars all stemmed from Realist logic — the relentless quest for power and deterrence.

Even today, when nations increase their defense budgets, engage in strategic alliances, or assert dominance in regional disputes, they are operating under Realist principles. Realism, therefore, remains not just a theory of the past but a living reality shaping global politics in the 21st century.

Liberalism: Theory, Development, and Key Arguments

Liberalism is an intellectual and political tradition that emphasizes the potential for cooperation, rule-based order, and progress through institutions, norms, and individual rights. At its core, liberalism argues that human beings are capable of mutual benefit, and that states — if embedded in supportive domestic and international institutions — can transcend zero-sum competition. Rather than treating international politics as driven solely by power, liberalism highlights how democracy, economic interdependence, legal frameworks, and transnational networks reduce incentives for conflict and create pathways for collective problem-solving.

The historical roots of liberal thought reach back to the Enlightenment. Thinkers such as John Locke articulated ideas of individual rights, consent of the governed, and limited government, while Immanuel Kant proposed a cosmopolitan vision where republican constitutions and a global federation of laws could produce durable peace. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, liberalism influenced movements for constitutionalism, free trade, and the rule of law — all seen as foundations for more peaceful international relations.

In the twentieth century, liberal ideas informed the post-Second World War architecture: institutions like the United Nations, Bretton Woods organizations, and multilateral treaties reflected a belief that formal rules and organizations could manage inter-state relations and channel competition into stable, predictable forms. Scholars developed several strands of liberal thought — institutional, normative, and commercial — each stressing different mechanisms through which liberalism reduces conflict.

Key arguments in favor of liberalism include: first, that institutions matter, because they reduce uncertainty through rules, transparency, and repeated interactions; second, that democratic states are less likely to go to war with one another (the democratic peace thesis); third, that economic interdependence raises the costs of conflict and creates mutual stakes in stability; and fourth, that transnational actors — from NGOs to multinational corporations — shape state preferences and broaden the sphere of cooperation beyond narrow security concerns.

Critics correctly point out that liberalism can be overly optimistic: institutions sometimes fail, democracies may still engage in coercive behavior, and economic ties do not automatically prevent rivalry. Yet, empirical cases — from trade-driven rapprochement to cooperative responses to transnational threats — suggest that liberal mechanisms often make cooperation more feasible and sustainable than a purely power-centric view predicts. Thus, liberalism offers both normative reasons (justice, rights, dignity) and pragmatic tools (treaties, courts, intergovernmental organizations) for managing global problems.

Ultimately, liberalism frames international politics not as a single story of conflict but as a plural story in which rules, values, and shared interests create enduring possibilities for collective action. It does not deny power's role; rather, it argues that power can be harnessed more productively when embedded in institutions and guided by norms that elevate cooperation over perpetual antagonism.

Institutional Liberalism vs. Ideational (Normative) Liberalism

Institutional Liberalism emphasizes the role of formal structures — treaties, international organizations, dispute-resolution mechanisms, and legal regimes — in shaping state behavior. From this perspective, institutions reduce transaction costs, provide information that mitigates mistrust, and create enforcement or reputational incentives that make cooperation durable. For example, trade agreements with dispute-settlement provisions lower the risk that economic tensions will escalate into political conflict. Institutional liberals therefore focus on design features: repetition, monitoring, verification, and sanctions.

By contrast, Ideational or Normative Liberalism stresses the power of ideas, identities, and moral commitments. This strand argues that values such as human rights, democratization, and shared norms transform state preferences themselves — not just the context in which choices are made. According to ideational liberals, normative shifts (for instance, the delegitimization of colonialism or apartheid) can create lasting changes in international behavior because states internalize new standards and domestic constituencies demand different policies.

While institutional liberals highlight structures and incentive systems, ideational liberals highlight belief systems and identity formation. In practice, the two are complementary: institutions can help spread and consolidate norms, and norms can strengthen the legitimacy and effectiveness of institutions. Together they explain how rules and values work in tandem to produce more cooperative international outcomes.

Examples of Global Institutions and Cooperation

There are many concrete instances where liberal mechanisms have facilitated cooperation. The United Nations provides a forum for diplomacy, peacekeeping mandates, and humanitarian coordination, helping states manage disputes without resorting to force. The World Trade Organization (WTO) established binding dispute settlement procedures that have, in many cases, resolved trade conflicts through legal means rather than unilateral measures.

Climate governance illustrates institutional cooperation: the Paris Agreement created a common framework for nationally determined contributions, transparency, and reporting — encouraging states to coordinate mitigation and adaptation policies. In public health, institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO) play a central role in disease surveillance, information-sharing, and technical assistance during pandemics.

Finally, regional bodies like the European Union demonstrate the depth of integration possible when economic interdependence, legal harmonization, and supranational institutions combine to lock in peace and cooperation among erstwhile rivals. These examples show how institutions and shared norms can convert potential conflict into sustained collaboration, illustrating the practical power of liberalism in today’s interconnected world.

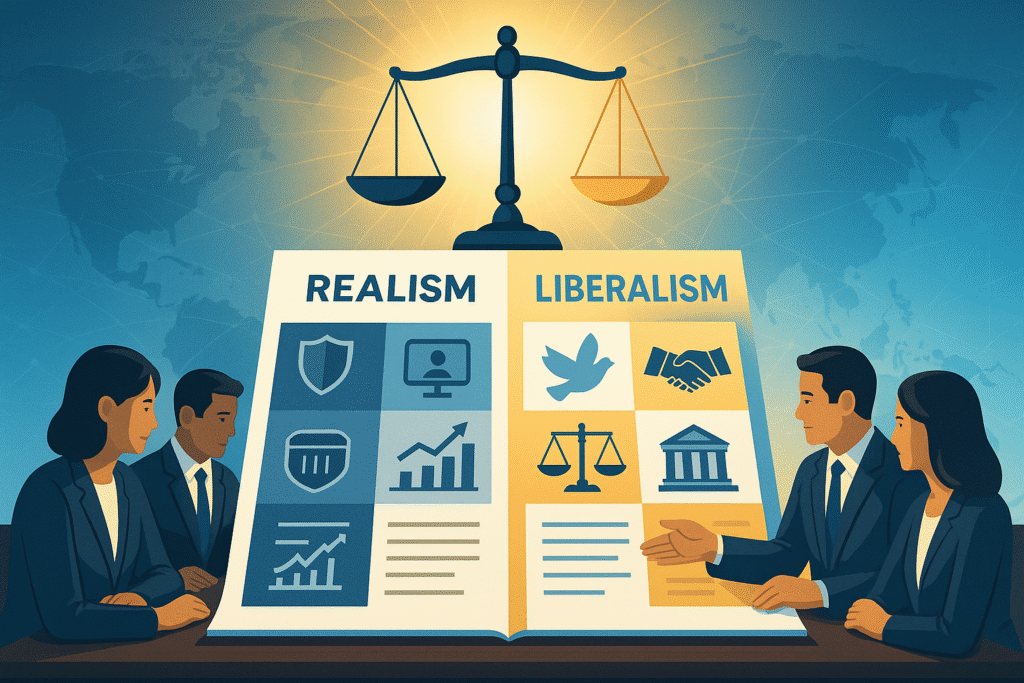

Realism vs. Liberalism: Comparison and Contestation

The debate between Realism and Liberalism forms the core of much scholarship and policymaking in international relations. While Realism emphasizes power, survival, and the competitive nature of states operating in an anarchic international system, Liberalism highlights institutions, norms, and interdependence as pathways to cooperation and peace. This tension is not merely academic: it shapes defense budgets, treaty design, diplomatic posture, economic policy, and public rhetoric. In practice, states and policymakers oscillate between these logics depending on perceived threats, domestic politics, and historical context. Understanding where the two theories converge and diverge helps clarify why some crises escalate into conflict while others are resolved through negotiation, and why some leaders prioritize short-term security gains whereas others invest in long-term institutional solutions.

Theoretical Differences

At a foundational level, Realism answers the question “what is” — it describes an international order defined by anarchy, where the absence of a central authority compels states to rely on self-help. Realists see states as unitary, rational actors whose primary objective is survival; this leads to familiar concepts such as balance-of-power politics, deterrence, and security competition. Morality and law are, in the realist view, subordinate to interest: ethical considerations matter only insofar as they coincide with national survival or advantage. By contrast, Liberalism is more prescriptive about “what can be.” Liberals contend that domestic institutions, economic linkages, and transnational ideas can transform state behavior. Where Realism focuses on material capabilities and structural constraints, Liberalism emphasizes how rules, repeated interactions, and norms reduce uncertainty and create incentives for cooperation. Democratic peace theory, the role of international organizations, and the stabilizing effects of commerce are all core liberal propositions. Conceptually, Realism is parsimonious and sceptical about ameliorative change; Liberalism is pluralistic and optimistic about the transformative potential of institutions and ideas.

Impact on Policy-Making

The influence of these theories manifests distinctly in policy design. A realist-informed policymaker prioritizes military readiness, strategic alliances, and sometimes unilateral measures to secure national interests. Policies derived from Realism often emphasize deterrence, force projection, and the cultivation of credible capabilities that dissuade adversaries. For example, states may expand their naval presence to protect sea lanes or form security pacts to prevent regional hegemony. Conversely, policymakers guided by Liberalism invest in international institutions, legal frameworks, and economic integration to lower the costs of cooperation and build mutual trust. They are more likely to pursue treaties, multilateral sanctions regimes, and cooperative frameworks for issues that cross borders — climate agreements, trade regimes, or arms control verification mechanisms. In practice, most governments blend both approaches: they maintain robust defense postures while participating in international institutions. The balance a government strikes often reflects strategic culture, threat perceptions, domestic political pressures, and the issue-area in question. Misalignment—such as relying exclusively on military tools in domains better suited to institutional cooperation—can produce policy failures; likewise, overreliance on institutions when immediate threats demand decisive action can leave a state vulnerable.

Example: Geopolitical Contestation

Geopolitical rivalries vividly illustrate the tug-of-war between Realist and Liberal prescriptions. Consider disputes over strategic waterways or contested maritime zones: a realist response typically emphasizes hard power—naval deployments, military bases, and defense partnerships—to secure access and deter competitors. A liberal response would stress legal claims, arbitration, confidence-building measures, and multilateral governance mechanisms to manage rival claims and reduce the risk of escalation. Similarly, when economic coercion (sanctions, trade restrictions) is used, Realists view these tools as instruments of statecraft to weaken adversaries, while Liberals worry that such measures can fracture interdependence and undermine institutions that foster cooperation. In many regional crises, the resolution path depends on which logic predominates: if Realist dynamics dominate, the result may be a frozen rivalry or military standoff; if Liberal mechanisms hold sway, negotiated settlements, institutional oversight, and joint management arrangements become more likely. Ultimately, the real world rarely offers pure theory—successful states and policies tend to combine credible deterrence with institutional engagement to manage risk while preserving opportunities for cooperation.

My Experience: A Personal Struggle Between Realism and Liberalism—and What I Learned

Over the course of my professional and community work, I have repeatedly confronted the gap between theory and practice — between what political philosophies promise and what real people will accept. On more than one occasion I found myself oscillating between two instincts: a realist instinct to secure immediate order and safety, and a liberal instinct to build institutions, encourage dialogue, and cultivate shared values. One particular episode taught me that neither approach alone is sufficient; the most durable results come from a pragmatic combination of both.

Several years ago I was asked to lead a local economic-recovery initiative in a region riven by longstanding mistrust and sporadic violence. The goal seemed straightforward: revive trade links, restore small-scale markets, and reconnect producers with buyers across fractured communities. My initial plan was informed by liberal assumptions — if we could create inclusive forums, offer training, and set up shared market infrastructure, trust would slowly rebuild and commerce would follow.

At first, the liberal approach showed promise. We organized stakeholder meetings, hosted joint training workshops, and launched a public information campaign that emphasized mutual benefits. Local media covered our efforts positively; a few small cooperation agreements were signed; and for a while the atmosphere felt hopeful. People spoke of partnership, and elders who had once been distant began to attend community gatherings again.

However, when we moved from symbolic gestures to practical implementation — addressing concrete issues like cross-border transport permits, security for goods in transit, and land-use disputes — dormant fears resurfaced. Some groups pulled back, citing safety concerns; others expressed suspicion that any cooperation would favor certain factions. Several meetings ended in heated exchanges, and a few participants stopped attending altogether. It became clear that goodwill and dialogue, while necessary, were not sufficient to overcome entrenched security anxieties.

Faced with stalled progress, I shifted tactics and introduced more realist, short-term measures to reduce uncertainty. We established a small monitoring team to provide guarantees of safe passage for traders, implemented limited checkpoints staffed by neutral observers, and negotiated time-bound operational protocols that clarified responsibilities. We also created an interim compensation scheme to offset immediate losses for businesses willing to participate in pilot exchanges. These concrete steps reduced fear and brought many stakeholders back to the table.

Yet even these realist measures had limits. Some community members felt constrained by surveillance and rules; they argued that constant oversight eroded trust rather than built it. Others feared that a security-first approach would cement unequal power relations. Recognizing this, we deliberately combined the immediate, realist measures with renewed investment in institutional, liberal-building processes: transparent grievance mechanisms, rotating leadership in local committees, and capacity-building programs that empowered marginalized groups to take leadership roles in trade governance.

Within months the hybrid approach began to produce measurable results. Small trade flows resumed, dispute incidents declined, and local entrepreneurs reported incremental increases in income. More importantly, relationships began to shift: where fear had once driven behavior, repeated positive interactions slowly created new expectations of reciprocity. The realist interventions had created the space for liberal institutions to take root; the institutions, in turn, helped to reduce the long-term costs of maintaining heavy security measures.

- Context matters: No single theory fits every situation. Effective decisions require careful reading of history, stakeholders, and incentives.

- Small, practical wins matter: Early, tangible improvements (safety guarantees, pilot programs) build momentum that ideals alone cannot generate.

- Institutions and norms are mutually reinforcing: Rules and transparency enable cooperation, but they need material support and enforcement mechanisms to be credible.

One additional insight stands out: morality and practicality are not necessarily opposed. In our case, liberal commitments to inclusion and fairness eventually reduced the need for coercive measures, while realist protections made inclusion feasible in the short term. In other words, pragmatic security measures can create the breathing room necessary for normative, institutional solutions to mature — and those normative solutions, once established, can reduce the long-term burden of force.

From a policy perspective, the episode taught me to design strategies that are sequenced and adaptive. Start with measures that reduce immediate risk and create incentives to participate; follow with institutional investments that lock in gains and broaden participation; and continuously solicit feedback so that policies evolve with changing realities. From a personal standpoint, the experience has made me more comfortable with complexity and less wedded to ideological purity. Theory is a compass, not a map; it helps orient action, but it must be tested and adjusted on the ground.

Ultimately, the smartest path — whether in international relations or community development — is one that recognizes the limits of pure theory and embraces a situational, hybrid approach. Realism supplies urgency and a focus on security; liberalism supplies vision and mechanisms for durable cooperation. When deployed together, prudently and ethically, they can produce outcomes that are both effective and just.

Practical Policy Takeaways

Balancing Realism and Liberalism in policy design requires clarity, sequencing, and adaptability. Effective policies address immediate security or stability concerns while also investing in longer-term institutional capacity—rules, transparency, and inclusive governance—that reduce future risks. Below are pragmatic recommendations for policymakers and implementers who want to harness the strengths of both approaches while minimizing their weaknesses.

- Sequencing: Begin with time-bound measures that reduce immediate risks and create space for dialogue. Follow up with institution-building, legal frameworks, and trust-building measures that lock in gains.

- Hybrid policy design: Combine hard measures (deterrence, monitoring, contingency plans) with soft measures (treaties, economic incentives, dispute-resolution mechanisms) so that security and cooperation reinforce each other.

- Local participation and subsidiarity: Avoid purely top-down solutions. Engage local stakeholders early to ensure policies are context-sensitive, legitimate, and more likely to be sustained.

- Clear metrics and monitoring: Define measurable indicators for short-term and long-term objectives. Regular evaluation allows for course correction and builds public confidence in the chosen approach.

- Proportionality and exit strategies: Design realist instruments (e.g., temporary safeguards, monitoring teams) with sunset clauses and clear exit criteria so they do not become permanent sources of resentment.

- Inclusive institutions: Invest in grievance mechanisms, transparency tools, and capacity-building so that liberal frameworks are credible and enforceable.

- Policy adaptability: Maintain feedback loops to adapt to changing circumstances—threat perception, economic shocks, or social dynamics—rather than relying on one static doctrine.

- Communication and narrative: Explain to publics why a mixed approach is necessary: short-term protections enable long-term cooperation, and institutional investments reduce the need for coercion.

In short, policymakers should view Realism and Liberalism as complementary toolkits. Use Realist measures to stabilize and protect, and Liberal instruments to build durable institutions that reduce the future need for force. Thoughtful sequencing, measurable targets, local legitimacy, and adaptive learning turn theory into effective practice.

When to Adopt a Realist Stance

Adopt a Realist posture when immediate threats to security, territorial integrity, or economic stability are present and delay would produce unacceptable harm. Typical scenarios include armed conflict, sudden cross-border incursions, major disruptions to critical supply chains, or abrupt economic shocks that threaten social order. In these situations, decisive, often unilateral or coalition-based, measures—such as targeted military deployments, emergency sanctions, temporary border controls, or rapid stabilization funds—can prevent escalation and protect civilians.

Realist measures are most effective when they are narrowly tailored, have clear objectives, and include exit criteria. They should be accompanied by transparency about goals and timeframes to avoid creating a sense that force or coercion will become permanent. Importantly, realist steps should be paired with a roadmap toward institutional solutions so that short-term security does not ossify into long-term repression or exclusion.

When Liberal Values and Instruments Are Most Useful

Liberal approaches are best suited for long-term, transnational, and structural problems where collective action and rule-based coordination produce returns that unilateral force cannot. Examples include climate change, pandemic preparedness, cross-border pollution, trade governance, and development challenges. In these domains, institutions, legal frameworks, transparency mechanisms, and economic interdependence create sustained incentives for cooperation and lower the costs of compliance.

Upholding liberal values—rule of law, human rights, inclusive participation—tends to be most effective when domestic institutions are sufficiently robust to implement international commitments and when stakeholders perceive institutions as legitimate. Investments in education, local governance capacity, judicial independence, and civil society strengthen the foundation upon which international agreements can succeed. Ultimately, liberal instruments reduce the long-run demand for coercive measures by addressing root causes and building resilient, cooperative systems.

Major Criticisms and Challenges

Both Realism and Liberalism have deeply influenced international relations, yet each faces substantive criticisms that expose their limits in an increasingly complex world. Realism is often attacked for its narrow focus on power and security, which can marginalize ethical concerns such as human rights, humanitarian protection, and democratic principles. By prioritizing state survival and strategic advantage, Realist policies risk normalizing coercive measures and overlooking the long-term social costs of repression, displacement, or economic isolation.

Liberalism, by contrast, is frequently criticized for its optimism about institutions and normative change. Critics argue that institutions can be weak, capture-prone, or ineffectual—especially when major powers decide to flout rules for strategic gain. Economic interdependence does not automatically prevent conflict, and democratic norms do not always translate into peaceful foreign policies. Moreover, the reliance on multilateral frameworks can create implementation gaps when domestic political will or administrative capacity is lacking.

Beyond these tradition-specific critiques, both paradigms encounter shared, contemporary challenges. Globalization, technological disruption, and transnational threats—cybersecurity, climate change, pandemics, and non-state violence—complicate policy tools that were developed primarily for great-power, territorially bound competition. The rise of asymmetric warfare, information operations, and economic coercion blurs the line between security and economic policy, making old categories less decisive.

Another problem is theoretical incompleteness: neither framework fully accounts for identity politics, domestic polarization, or the role of non-state actors whose influence often transcends state boundaries. Finally, there is the risk of doctrinal rigidity—when policymakers lean too heavily on a single paradigm, they may overlook context-specific hybrid strategies that combine deterrence, diplomacy, institutions, and norms.

In practice, resolving these criticisms requires intellectual and policy pluralism: adopting flexible, context-sensitive approaches that draw on the strengths of both Realism and Liberalism while remaining responsive to novel threats, technological shifts, and the moral demands of contemporary politics.

Conclusion & Next Steps

Realism and Liberalism each offer powerful lenses for interpreting world affairs: Realism underscores the importance of security, power, and pragmatic constraints, while Liberalism highlights institutions, norms, and the possibilities of cooperation. The most effective strategies often combine both — using short-term, targeted measures to manage immediate risks and investing in institutions and shared norms to reduce future conflicts. Context, sequencing, and adaptability are the real tools of wise policy-making.

FAQ — Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the main difference between Realism and Liberalism?

In short: Realism emphasizes power, security, and state interests in an anarchic international system; Liberalism emphasizes institutions, norms, and interdependence as pathways to cooperation. Realism describes “what is”; Liberalism suggests “what can be.”

2. Is it ever safe to rely entirely on one theory?

No. Relying solely on Realism risks neglecting long-term cooperation and humanitarian costs, while relying only on Liberalism can leave states vulnerable to immediate threats. Most effective strategies combine elements of both, adapted to context.

3. Does the democratic peace theory prove Liberalism is correct?

Democratic peace theory shows that stable democracies are less likely to fight one another, which supports a core liberal claim. However, it is not universal—context, leadership, and external pressures also shape outcomes.

4. How do these theories matter in everyday life?

At the personal level, the debate mirrors choices between pragmatism and principle. Practically, it advises whether to prioritize immediate, security-oriented measures or invest in longer-term, institution-building solutions—and often both in sequence.

5. Which approach works better for modern challenges like climate change or cyber threats?

Transnational problems generally require liberal instruments—treaties, institutions, and cooperative frameworks—but they also often need immediate realist-style measures (rapid emergency responses, sanctions, or defensive capabilities). A hybrid, situational approach is typically most effective.

References

Note: The references below are sample entries — update publication years, translations, and URLs as per your use. Always include rel="noopener noreferrer" in external links for security and open them in a new tab with target="_blank".

- Thucydides. — The History of the Peloponnesian War. (Classical Text).

- Niccolò Machiavelli. — The Prince. (Translation and publication details).

- Thomas Hobbes. — Leviathan. (1651).

- Hans Morgenthau. — Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. (Publication year, Publisher).

- Kenneth Waltz. — Theory of International Politics. (Publication year, Publisher).

- Immanuel Kant. — Perpetual Peace. (Essay).

- John Locke. — Two Treatises of Government. (For philosophical reference and analysis).

- United Nations (UN). — UN Charter. (1945). Read the UN Charter

- Paris Agreement. — UNFCCC, 2015. Official Paris Agreement Source

- World Health Organization (WHO). — Reports and global health policy frameworks (e.g., pandemic preparedness plans). WHO Official Website

- World Trade Organization (WTO). — Dispute settlement reports and trade governance documents. WTO Official Source

- Additional contemporary sources: — Include academic journal articles, policy briefs, and verified online publications used for analysis; cite them here in APA, MLA, or Chicago style as required.

Reference Style Tip: For academic or professional use, follow a consistent format (APA, Chicago, or MLA). When referencing websites, always include the publication date and the date accessed.