Introduction — Exploring the Urban Genius of the Indus Valley Civilization

When we look at the challenges of modern cities—traffic congestion, unplanned construction, water scarcity, polluted drains, and chaotic urban expansion—we often assume that urban planning is a modern invention. Yet the truth is far more fascinating. Thousands of years ago, when most regions of the world were limited to small agricultural settlements, a remarkable civilization was flourishing on the Indian subcontinent. This civilization not only built advanced city structures but created an exemplary model of urban design. This was the Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization.

What makes this civilization extraordinary is the fact that its cities were not merely places to live—they were carefully planned, well-organized, and based on highly scientific principles. The grid-patterned streets, private bathing areas within homes, underground drainage systems, rainwater harvesting structures, massive reservoirs, and public buildings were not just remarkable for their time—they were more advanced than many urban centers that appeared thousands of years later across the world.

As we study the urban planning of the Indus Valley Civilization in the context of today’s urban challenges, it becomes clear that they had conceptualized the essence of a “smart city” long before the term existed. Their construction approach not only focused on structural efficiency and aesthetics but also gave prime importance to health, sanitation, environmental sustainability, public convenience, and community living. Such features reveal that the people of that era were not just skilled builders but visionary planners who understood the deeper needs of urban life.

In this article, we will explore the core features of the Indus Valley urban planning system— including its technical aspects, water management strategies, drainage networks, street layouts, residential architectures, and the unique characteristics of major sites such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira. Along with this, I will share insights from my own learning journey, highlighting what modern cities and planners can adopt from this ancient civilization. It is not just a study of the past—it's a gateway to rethinking the future of sustainable urban development.

My Personal Journey — How an Ancient Civilization Changed My Modern Perspective

A few years ago, I was wandering through a small local museum in my city. The hall was filled with artifacts—potsherds, tools, coins, and sculptures. But among all those objects, my attention was captured by a single, rectangular brick displayed inside a glass box. It had come from the excavations of Harappa. At first glance, it looked like an ordinary brick, but its proportions were so precise, so mathematically balanced, that it made me pause. A simple question arose in my mind: “Could people thousands of years ago really be this advanced?” That moment silently pulled me toward the world of the Indus Valley Civilization and its extraordinary urban planning.

As I continued reading and researching, my curiosity turned into fascination. The more I learned, the more I realized how sophisticated their cities truly were. I still remember the first time I saw an image of the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro. My immediate reaction was disbelief—“How can a 4500-year-old structure look more refined and functional than many modern water systems?” That thought stayed with me, and it marked the beginning of my deeper exploration into their planning genius.

I soon decided that I would not study the Indus Valley Civilization merely as a historical subject, but as a blueprint for understanding modern development. When I examined their grid-pattern streets, uniform brick ratios, underground drainage, carefully aligned residential blocks, rainwater harvesting practices, and public spaces, a vivid picture slowly formed in my mind. It felt as if I was walking through one of their ancient cities—imagining the sound of footsteps on those straight streets, the flow of water through the covered drains, and the everyday life of people who valued order, hygiene, and community living.

Another moment that deeply moved me came while watching a documentary on Dholavira’s water management system. The film showed how the settlers of that region used natural slopes and terrain to channel every drop of rainfall into massive interconnected reservoirs. The ingenuity of that design struck me. At a time when today’s cities struggle with both water scarcity and flooding, here was a civilization that had solved the problem with astonishing scientific understanding—thousands of years earlier. It made me feel a strange connection, as if their wisdom was silently speaking to us across time.

Gradually, I realized that the Indus Valley Civilization is more than an archaeological chapter. It is a living testament to human intelligence, planning, and collective responsibility. These people did not just build cities—they built communities that prioritized cleanliness, water conservation, public convenience, and social harmony. Their urban planning was not just technical; it was deeply humane. And that realization changed something within me.

Even today, whenever I see the unplanned colonies, overflowing drains, or chaotic water supply systems of modern cities, my mind instinctively goes back to Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira. I wonder how a civilization so ancient could be so advanced, and how our era—despite all technological progress—still struggles with issues they had already solved. That contrast inspires me to look deeper into their planning approach.

This personal journey was not just an academic exploration; it was a transformative experience. It taught me that ancient knowledge is not merely meant to be admired in museums—it is meant to guide the present and inspire the future. And with that sense of purpose, I now take you into the remarkable world of the Indus Valley Civilization, where every brick, every street, and every drain holds a lesson for the modern world.

Indus Valley Civilization — A Brief Historical Background

The Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, is regarded as one of the world’s earliest and most advanced urban cultures. Flourishing roughly between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE, this civilization spread across a vast region that includes present-day Pakistan, northwest India, and parts of western India. At a time when Egypt and Mesopotamia were developing their own urban centers, the Indus Valley people had already mastered the art of planned city-building, technological innovation, and organized social life.

The civilization extended over nearly 1.2 million square kilometers, making it one of the largest Bronze Age civilizations in the world. Major sites such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Kalibangan, Lothal, Rakhigarhi, and Banawali showcase a remarkable uniformity in planning and construction. Grid-patterned streets, standardized brick ratios, advanced water management systems, and carefully designed residential structures reflect a highly systematic and scientific approach to urban development.

Archaeological discoveries reveal that the Indus people excelled in agriculture, trade, metallurgy, bead-making, pottery, and craft specialization. The presence of Lothal’s dockyard indicates their proficiency in maritime trade. Structures like granaries, private bathing areas in homes, and large public buildings at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro suggest a well-organized socio-economic system that valued hygiene, storage efficiency, and community welfare.

The script of the Indus Valley Civilization—still undeciphered—adds an aura of mystery to this ancient culture. Symbols preserved on seals, pottery, and metal objects hint at a structured administrative and economic order. Although scholars have not been able to fully understand the language, the uniform patterns in symbols and inscriptions suggest a highly sophisticated communication system.

Various theories attempt to explain the decline of this civilization, including climate change, shifting river courses, resource depletion, floods, and the gradual breakdown of long-distance trade. No single theory has been universally accepted, but archaeologists generally agree that the decline was not sudden. Instead, it occurred over several centuries as environmental and socio-economic changes slowly weakened the urban system.

In summary, the Indus Valley Civilization is far more than an ancient chapter in history. It stands as a remarkable example of human intelligence, collective organization, and sustainable urban planning. Long before modern cities began to address issues like sanitation, water management, and civic infrastructure, the people of the Indus Valley had already developed practical and effective solutions. In today’s world—struggling with rapid urbanization, environmental crises, and infrastructure challenges—this civilization reminds us that even thousands of years ago, human societies understood the value of planning, structure, and harmony with nature.

Urban Planning — Key Elements of the Indus Valley Civilization

Grid and Planning Pattern

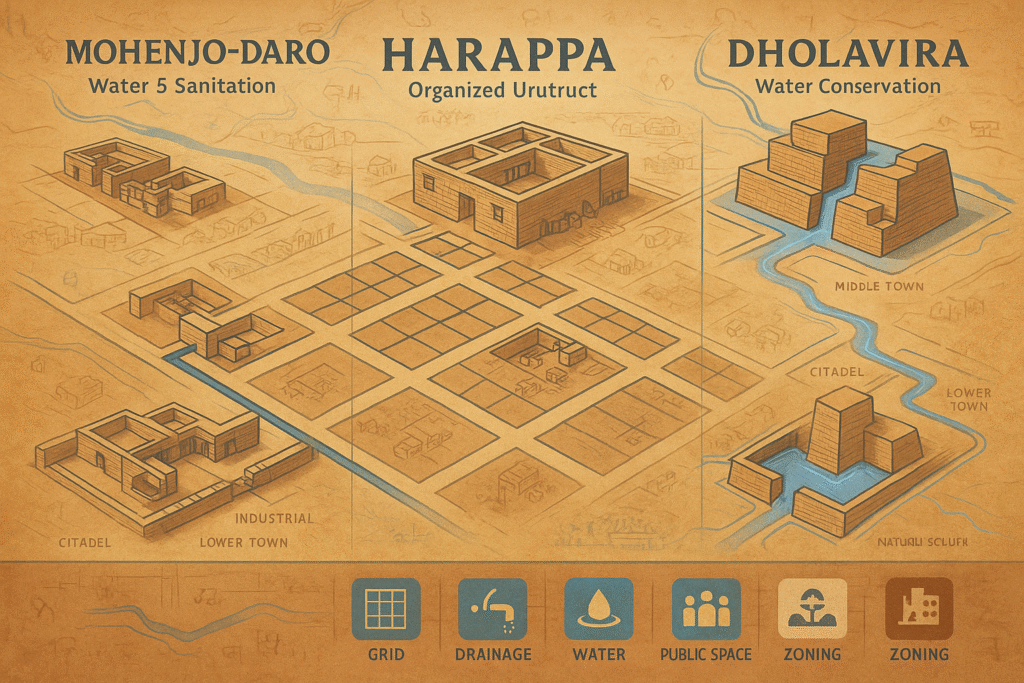

One of the most striking features of Indus urbanism is the regular grid pattern that structures its major cities. Streets often ran at right angles, dividing settlements into neat blocks and lanes. This orthogonal layout is evident at Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and Dholavira, where planners designed broad main avenues for circulation and narrower side streets for residential access. The grid not only created an orderly aesthetic but served multiple practical functions — it simplified land allocation, enabled efficient movement, and made public services such as drainage and water distribution easier to implement along predictable routes.

Standardised brick sizes and modular building practices complemented the street grid. Houses, workshops and public structures followed proportional layouts that fit into the larger block geometry, creating visual and functional harmony across the settlement. The repetitive block arrangement also allowed townspeople to expand or reorganise neighbourhoods without disrupting the whole city’s fabric — a resilient trait for an urban system.

The grid approach further reflects an implicit concern for climate and comfort. Straight, north–south and east–west streets channelled prevailing winds and provided better daylighting for houses and courtyards. In emergencies like fires, the regular street network facilitated faster evacuation. Overall, the Indus grid demonstrates a level of urban foresight that balances administrative control, public health, and everyday usability.

Modern relevance

Contemporary planners still praise grid systems for their legibility and adaptability. The Indus example reminds modern cities that clear street hierarchies, modular lots and standardised construction norms contribute to long-term manageability and incremental growth.

Drainage and Sewage System

The Indus cities developed one of the earliest and most comprehensive urban sanitation systems known in antiquity. Covered brick drains lined many streets and connected household outlets to larger public channels. These drains were often built with stone or baked-brick covers, forming enclosed conduits that reduced odour, limited disease vectors, and kept pathways clean and usable. Regularly spaced manholes or inspection chambers enabled maintenance — a sign of practical, long-term engineering thinking.

Inside many homes archaeologists have found private bathing areas and latrine outlets that fed into the municipal network. The presence of household-level plumbing indicates that sanitation was not merely civic infrastructure but woven into domestic life. The system’s gradient and careful alignment ensured flow without stagnation, demonstrating knowledge of hydraulics and urban hygiene uncommon for the era.

In addition to sanitation, the drainage network managed stormwater. By separating waste flow from surface runoff in many locations, the Indus planners reduced flood risk and preserved water quality in storage tanks and wells. This combination of drainage, waste disposal and stormwater control represents a holistic approach to urban water management.

Modern relevance

The Indus model highlights the value of integrated, maintainable sanitation systems. Today’s cities can learn from its emphasis on household connections, covered drains, and planned access points for cleaning and repair.

Water Management and the Use of Tanks and Wells

Water stewardship was central to Indus urban life. Cities incorporated wells, reservoirs, and engineered tanks to secure reliable supplies and to store monsoon runoff. Dholavira’s series of meticulously constructed reservoirs and channels is a hallmark example: planners used natural contours to collect rainwater into stepped tanks and earthen cisterns, enabling year-round access in an otherwise arid zone.

In many settlements, houses had private wells or shared neighbourhood wells. These sources were connected, directly or indirectly, to household water usage and local drainage, creating an integrated water economy. Granaries and public baths — such as Mohenjo-daro’s Great Bath — also testify to large-scale water control for ritual, hygienic and civic functions. Materials and workmanship in tank linings and masonry show awareness of seepage control and durability.

This systematic capture, storage and distribution of water balanced seasonal variability and reduced vulnerability to droughts. The Indus planners combined small-scale, household solutions (wells and rooftop catchment) with large, communal infrastructure (reservoirs and channels), achieving both redundancy and scale.

Modern relevance

Contemporary water-scarce regions can draw lessons from this mixed strategy: combine decentralised harvesting with central storage, use landscape contours for passive collection, and design for maintenance and long-term durability.

Public and Semi-Public Spaces, Workshops, Citadel and Residential Units

Indus cities reveal a clear spatial distinction between civic complexes and everyday neighbourhoods. Elevated citadel areas frequently contained large public structures, granaries, ceremonial platforms and administrative buildings, while the lower town hosted dense domestic quarters and craft workshops. The spatial segregation allowed cities to support specialised economic activities alongside communal functions.

Workshops for bead-making, metallurgy, and pottery are archaeologically visible as clustered units with adjacent storage and work surfaces. Commercial areas and dockyards (for example, at Lothal) indicate organised trade networks and production planning. Public amenities — baths, large storage facilities, and open courtyards — functioned as focal points for social and civic life, strengthening communal identity.

Residential units ranged from modest single-room houses to multi-room dwellings with internal courtyards, private bathing spaces, and service alleys. The courtyard house offered light, ventilation and a microclimate for domestic activities. The recurring pattern of household design, combined with access to drains and wells, shows that everyday comfort and hygiene were integral to urban form.

Modern relevance

The Indus spatial model underscores the importance of mixed-use planning: protected civic cores, proximate artisan zones, and human-scale housing with access to public amenities. Modern planners can emulate this balance to promote economic resilience, social cohesion and livable neighbourhoods.

Case Studies: Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira

Harappa — A Model of Organized Urban Structure

Harappa, the first discovered city of the Indus Valley Civilization, stands as a remarkable example of planned urban development. Excavations reveal that Harappa was divided into distinct zones— residential blocks, administrative complexes, industrial areas, and storage facilities—indicating deliberate and well-structured urban planning. Streets followed a clear grid pattern, with north–south and east–west orientations, creating orderly rectangular blocks that facilitated movement, ventilation, and efficient city management.

One of the most iconic structures at Harappa is the granary, built with massive brick platforms and spacious ventilated rooms. Its size and layout suggest centralized storage and a structured system of distribution, illustrating the economic organization of the city. Harappa’s drainage system also reflects advanced engineering: each household discharged wastewater through covered drains that connected to larger public channels, making sanitation a central feature of daily life.

Harappa was a major center for crafts, including bead-making, pottery, metallurgy, and shell work. Industrial workshops were strategically located away from residential clusters, ensuring safety, reducing pollution, and maintaining order. Such zoning principles mirror the modern concepts of industrial planning and sustainable land use.

Overall, Harappa represents a sophisticated blend of organization, technology, and community-focused design. Its structured layout, standardized construction methods, and attention to hygiene show that ancient planners held a clear vision for building harmonious and efficient cities. Harappa continues to be an essential reference point for understanding the architectural and administrative intelligence of the ancient world.

Mohenjo-daro — A Masterpiece of Water and Sanitation Engineering

Mohenjo-daro is one of the most iconic cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, celebrated globally for its advanced water management and sanitation systems. The most famous structure—the Great Bath— is a testament to the city’s architectural brilliance. Built with watertight bricks and bitumen lining, the bath featured an elaborate drainage and freshwater inlet system. Its design suggests not only ritualistic or cultural importance but also a high level of public hygiene awareness.

The city's street layout was extremely organized, with wide avenues and narrow side lanes meeting at right angles. Residential houses often included private bathing areas, internal courtyards, and separate waste channels that connected directly to the main covered drains running along the streets. This sophisticated sanitation network is considered one of the earliest examples of an integrated urban sewage system in human history.

Mohenjo-daro was also a hub of commercial and craft activities. Evidence of bead workshops, metal tools, copper artifacts, and long-distance trade items highlights the city’s economic vibrancy. The division between the Citadel (public and administrative buildings) and the Lower Town (residential and economic areas) shows a planned distribution of spaces based on function and community needs.

In essence, Mohenjo-daro showcases how early urban societies understood the importance of cleanliness, public infrastructure, and organized civic life. Its water supply, waste disposal, and architectural planning provide valuable insights into a civilization that was far ahead of its time.

Dholavira — A Masterclass in Water Conservation and Urban Innovation

Dholavira, located in the arid region of Kutch in Gujarat, is one of the most extraordinary cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Unlike other sites, Dholavira showcases an unparalleled mastery over water conservation. The city’s planners ingeniously used natural slopes, rock formations, and channel systems to collect rainwater into massive interconnected reservoirs. These reservoirs were designed to store enough water to sustain the population through long periods of drought.

Dholavira’s urban layout is unique. The city was divided into three major zones— the Citadel, the Middle Town, and the Lower Town—each separated by fortified walls and gateways. This hierarchical planning demonstrates an advanced understanding of security, administration, and social organization. The use of large stone blocks, multi-layered water tanks, and meticulously aligned streets further indicates an exceptional level of engineering precision.

One of Dholavira’s most remarkable discoveries is the large signboard carved with symbols of the Indus script. This suggests the presence of an administrative system and points to the importance of communication and record-keeping in urban governance. Excavations also reveal well-planned residential structures, workshops, ceremonial spaces, and storage systems.

In today’s context of water scarcity and climate challenges, Dholavira stands as an inspiring demonstration of sustainable resource management. It shows that even in harsh environments, long-term survival is possible through intelligent planning, community coordination, and respect for natural resources.

Lessons for Modern Urban Planners and Comparative Insights

The urban planning principles of the Indus Valley Civilization are not merely archaeological achievements; they are practical models that hold relevance even today. In a world facing rapid urbanization, water scarcity, pollution, and unplanned settlement growth, the Indus cities offer timeless lessons in sustainability, efficiency, and community-centric development. Their city-making approach demonstrates that intelligent design and long-term vision are essential for creating healthy, livable and resilient urban spaces.

1. Planned Grid Layout — A Solution for Mobility and Land Management

The grid-based street system of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro is strikingly similar to modern urban planning principles. Straight roads intersecting at right angles ensured smooth movement, reduced congestion, and improved spatial organization. Today, many growing cities suffer from chaotic expansion and traffic disorders. The Indus model teaches that geometrically disciplined layouts, hierarchical streets, and modular blocks are key to long-term urban stability. A well-structured grid not only enhances mobility but also simplifies infrastructure planning and land allocation.

2. Drainage and Sanitation — The Foundation of Public Health

Modern cities frequently face challenges such as waterlogging, sewage overflow, and pollution. The Indus model of covered drains, household-level wastewater outlets, and regular inspection chambers highlights the importance of integrated sanitation networks. Their system reveals a clear understanding that urban hygiene is not a matter of short-term action but robust infrastructure. Cities today can greatly benefit from adopting similar principles: proper gradients, closed drainage channels, and periodic cleaning mechanisms.

3. Water Conservation — The Core of Sustainable Urban Living

Dholavira’s exceptional water management system is a powerful lesson for today’s drought-prone regions. Large reservoirs, rainwater harvesting structures, and the intelligent use of natural slopes demonstrate how urban design can adapt to environmental conditions. Modern megacities often depend heavily on external water sources, yet overlook local collection systems. The Indus approach teaches that decentralised harvesting combined with central storage ensures long-term water security and reduces pressure on groundwater.

4. Public and Semi-Public Spaces — Strengthening Social Harmony

The public structures of the Indus cities — such as the Great Bath, open courtyards, and communal platforms — reflect a deep understanding of social interaction. As modern cities grow denser, community engagement is declining. Public spaces that encourage gatherings, culture, and shared activities can restore social balance. The Indus example proves that well-designed public spaces not only enhance urban beauty but also nurture cooperation, mental well-being, and social cohesion.

5. Balanced Zoning Between Residential and Industrial Sectors

In the Indus cities, workshops and industrial clusters were kept separate from residential zones. This prevented pollution, reduced risks, and preserved peace in daily life. Today, many cities struggle with mixed and unregulated land use. The Harappan model underscores the importance of zoning laws that ensure safety, reduce environmental impact, and maintain a harmonious relationship between industry and community spaces.

Ultimately, the Indus Valley Civilization teaches us that sustainable cities arise from the combination of strong infrastructure, community awareness, environmental sensitivity, and a long-term vision. Their planning philosophy, thousands of years old, remains profoundly relevant for shaping the future of modern urban life.

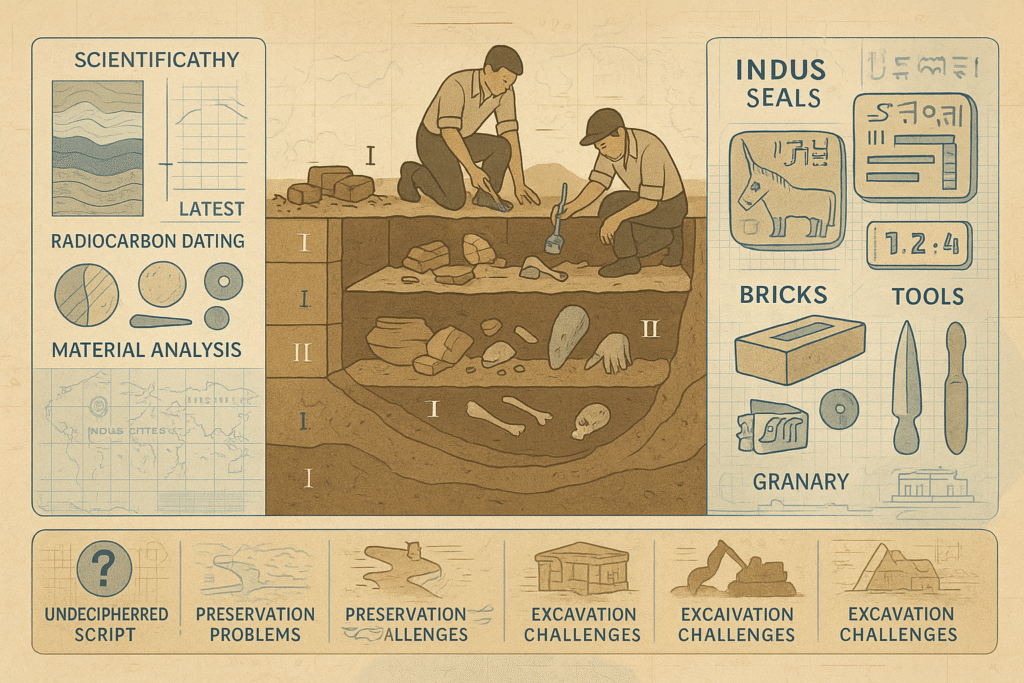

Archaeological Methods and Evidence

The study of the Indus Valley Civilization relies heavily on systematic archaeological methods that reveal the cultural, technological and urban sophistication of this ancient society. For over a century, archaeologists have conducted extensive excavations at major sites such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, Lothal and Kalibangan. The primary investigative techniques include stratigraphy, radiocarbon dating, topographical surveys, GIS-based mapping, and material analysis.

Stratigraphy, the study of layered soil deposits, provides insights into the chronological development of each settlement. For example, the multiple construction layers found at Mohenjo-daro indicate periodic rebuilding and structural evolution over several centuries. Radiocarbon dating helps determine the age of organic materials—such as wood, seeds, bones and charcoal—allowing researchers to establish the civilization’s timeline between approximately 2600 and 1900 BCE.

Detailed analysis of artifacts such as pottery, beads, seals, metal implements and standardized bricks reveals the technological expertise and daily lifestyles of the Indus people. The famous Indus seals, inscribed with undeciphered script and animal motifs, provide evidence of administrative control, trade activities and cultural symbolism. Large public structures such as granaries, wells, reservoirs, baths and covered drains further demonstrate advanced urban planning and collective living practices.

Modern tools like satellite imagery, remote sensing, and GIS mapping have expanded our understanding of settlement layouts, trade routes and environmental patterns. These technologies confirm that Indus cities were highly planned, with organized industrial zones, water systems and long-distance communication networks.

Overall, archaeological methods and evidence collectively reveal that the Indus Valley Civilization was not only ancient but remarkably advanced. Its scientific planning, architectural precision and sustainable practices make it one of the most significant urban cultures in human history.

Debates and Challenges

The study of the Indus Valley Civilization is filled with unresolved debates and significant challenges that continue to intrigue archaeologists. One of the most persistent issues is the undeciphered Indus script. Although thousands of seals, pottery markings and inscriptions have been discovered, the meaning of the symbols remains unknown. Without a readable script, scholars struggle to fully understand the political system, religious beliefs and social hierarchy of the civilization.

Another major challenge is the preservation of archaeological sites. Many settlements face deterioration due to environmental factors such as rising groundwater levels, salinity, climate change and erosion. Human activities—including encroachment, construction, and illegal excavations— further threaten the fragile remains. Additionally, there is ongoing debate about the causes of the civilization’s decline. Some theories point to river shifts, others to climate change, trade disruptions or gradual socio-economic transformations, but no single explanation has been universally accepted.

Despite these challenges, continuous research and modern scientific tools such as satellite imaging, GIS mapping and advanced dating techniques are helping refine our understanding. The unresolved debates ensure that the Indus Valley Civilization remains one of the most fascinating chapters in human history.

Conclusion and Call to Action

The urban planning legacy of the Indus Valley Civilization stands as a remarkable reminder that sustainable living, organized infrastructure and community-driven development were understood and practiced thousands of years ago. Cities like Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and Dholavira demonstrate how thoughtful design—combined with sanitation, water conservation and balanced zoning—can create resilient, healthy and harmonious societies. At a time when modern cities struggle with pollution, water shortages and unplanned expansion, the Indus model offers a timeless blueprint for a better urban future.

Ultimately, this civilization teaches us that lasting progress does not come only from technology, but from intelligent planning, environmental awareness and collective responsibility. If modern planners integrate even a fraction of these principles into today’s cities, the quality of urban life for future generations can be transformed.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why is the urban planning of the Indus Valley Civilization considered so advanced?

The urban planning of the Indus Valley Civilization is considered advanced because it featured grid-based street layouts, covered drainage systems, standardized brick ratios, private bathing areas, water harvesting structures and clearly defined residential and industrial zones. These elements reflect scientific thinking and organized civic design comparable to many modern urban models.

2. Was the drainage system of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro similar to modern cities?

Yes, in many ways their drainage system was even more efficient. Almost every house had a direct wastewater outlet connected to covered, well-graded brick drains running along the streets. Inspection chambers were provided for cleaning and maintenance. The focus on hygiene and sanitation makes their system remarkably similar to, and in some aspects superior to, modern drainage networks.

3. Why is Dholavira’s water management considered unique?

Dholavira’s water management system is unique due to its large reservoirs, interconnected channels, rainwater harvesting structures and the intelligent use of natural slopes. Located in an arid region, Dholavira demonstrates how ancient planners created a sustainable model that ensured year-round water supply even in harsh climatic conditions.

4. Is it possible to decipher the Indus script?

As of now, the Indus script remains undeciphered. Despite the discovery of thousands of seals and inscriptions, linguists have not been able to decode its meaning. If the script is ever deciphered, it could reveal vital insights into governance, religion, economy and everyday life in the Indus Valley Civilization.

5. What key lessons can modern urban planners learn from the Indus Valley Civilization?

Modern planners can learn several important lessons—such as adopting grid-based planning, prioritizing sanitation and drainage, integrating water conservation practices, maintaining a balance between residential and industrial areas and creating public spaces that support social harmony. These principles remain essential for building resilient, sustainable and healthy urban environments today.

References and Further Reading

- Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) — Official excavation reports and publications related to the Indus Valley Civilization.

- Book: “The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective” by Gregory L. Possehl — A comprehensive study of Indus history, culture and urban planning.

- Book: “The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives” by Jane McIntosh — An in-depth exploration of urbanism, society, technology and economic systems.

- Excavation Reports of Lothal, Dholavira, Kalibangan and Harappa — Published by the Archaeological Survey of India and international research teams.

- Research Paper: “Urban Planning in the Indus Valley Civilization” — Published in journals such as the Journal of Archaeological Research and Antiquity.

- National Museum, New Delhi — Collections and educational resources on artifacts from the Indus Valley Civilization.

- International Research Projects — Harvard, Cambridge and other universities conducting studies on Indus script, water management and settlement patterns.