The Third Battle of Panipat – Reasons, Strategy, Results & Its Place in Indian History

Introduction

The Third Panipat War is a very decisive and bloody chapter of Indian history. This war was fought on 14 January 1761 between the Maratha Empire and Ahmed Shah Abdali, a battle that changed the political direction of the entire North India. It was not only a military conflict, but also exposed the decisive point of the balance of powers in India.

Background of the War

Expansion of the Maratha Empire

- By the middle of the 18th century, the Maratha Empire had established its influence from the south to Delhi and Punjab.

- From Attock (present Pakistan) to Cuttack (Odisha), Maratha power was dominant.

- Mughal power had become nominal and the Marathas had become the most influential force in India.

Ahmed Shah Abdali’s Ambition

- Afghan ruler Ahmed Shah Abdali had invaded India several times before this.

- His intention was to take control of Delhi and Punjab and plunder them.

- He formed a strong army by allying with the Rohilla chieftains and Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula of Awadh.

Strategy and Events Before the Battle

Maratha Preparations

- The Maratha army was led by Sadashivrao Bhau, cousin of the Peshwa.

- He marched to Delhi with a huge army and artillery to stop Abdali.

- A trained infantry under the leadership of Vishnu Gardi also accompanied him.

Supplies and Strategic Mistakes

- The Maratha army was very large, but its supply system was weakening.

- Abdali cut off the logistics and communication routes, sensing this weakness.

Main Battle – 14 January 1761

Beginning of the Battle

- The Maratha army, suffering from severe cold and hunger, entered the battlefield under compulsion.

- Initially, the Marathas gained the upper hand and the first lines of the Afghans began to break.

Turning Point

- Abdali’s cavalry and Rohilla warriors attacked the Maratha supply lines.

- Sadashivrao Bhau and Vishwasrao were killed, shattering Maratha morale.

End of the Battle

- The Maratha army was completely routed.

- Thousands of soldiers were killed and many were captured and executed.

Consequences

- More than 70,000 people were killed, including a large number of Maratha soldiers.

- A large number of prisoners were massacred after the battle.

- The Maratha Empire suffered heavy losses and its influence in North India almost ended.

- Although Abdali won, he could not rule India and soon returned.

Historical Significance

- This battle was one of the bloodiest battles in Indian history.

- The Maratha Empire took several decades to recover.

- The defeat created a political vacuum, paving the way for the rise of the British East India Company.

Conclusion

The Third Panipat War was not just a military conflict but a political earthquake that changed the direction of the Indian subcontinent. This war became a symbol of valor and sacrifice in Maratha history.

📚 Key Sources and References

- Uday Kulkarni – Solstice at Panipat

- T.S. Shejwalkar – Panipat 1761

- Hari Ram Gupta – Marathas and Panipat

- Britannica: Battles of Panipat

- Wikipedia: Third Battle of Panipat

Introduction

The 18th century in India was marked by political instability and intense power struggles. The Mughal Empire was weakening day by day, while the Maratha Empire was rapidly expanding its dominance throughout the country. During this turbulent time, the Afghan ruler Ahmed Shah Abdali once again decided to invade India.

The Third Battle of Panipat, fought on 14 January 1761 on the battlefield of Panipat, became a decisive turning point in the history of the Indian subcontinent. It was not merely a clash between two powers — the Maratha Empire and the Afghan invaders — but a struggle that shaped India’s political direction, balance of power, and social structure.

Millions of soldiers participated in this war, and thousands sacrificed their lives. The outcome proved disastrous for the Maratha Empire and paved the way for the expansion of British power in India.

Background of the War

The mid-18th century India was politically chaotic. The Mughal Empire was weakening, and its authority had become nominal. Taking advantage of this political vacuum, the Maratha Empire expanded its influence deep into northern India.

Expansion of the Maratha Empire

Under the leadership of Peshwa Bajirao I and his successors, the Marathas established dominance from southern India to Delhi and Punjab. They subdued the Mughals and controlled the political reins of Delhi. However, this rapid expansion eventually became a challenge for them.

Ahmed Shah Abdali’s Intervention

Ahmed Shah Abdali (Durrani), the Afghan ruler, had already invaded India multiple times. He viewed the rising Maratha power as a threat, especially after the Marathas expelled his son Timur Shah from Punjab and captured Lahore and Sirhind.

Seeing this threat, Abdali planned a decisive war in India. He formed a powerful alliance with Rohilla Pashtuns (Najib-ud-Daula) and Shuja-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Awadh.

Clash of Two Great Powers

Peshwa Balaji Bajirao sent his cousin Sadashivrao Bhau with a massive army to defend Delhi and Punjab. This army consisted of Maratha chiefs, trained cavalry, artillery, and infantry specially prepared to counter Abdali.

But it was not just a battle between two armies — it was a clash of two ideologies: one representing indigenous Indian rule, and the other representing the tradition of foreign invasions in India.

Maratha Influence in Delhi and Punjab

By the mid-18th century, the Maratha Empire had established complete dominance in the Indian political landscape. Under the leadership of Peshwa Bajirao I and his successors, the Marathas not only strengthened their presence in the south but also entered northern India with remarkable confidence.

Control Over Delhi

- The Mughal Empire was collapsing, and the emperor had become a nominal figure.

- In 1752, the Marathas assumed the role of “Superintendent of Mughal Affairs,” taking charge of Delhi’s administration.

- In 1757, after Abdali’s attack on Delhi, the Marathas regained control of the capital.

- Mughal Emperor Alamgir II lived under Maratha protection, and defense of Delhi was handled by Maratha forces.

Victory in Punjab

- In 1758, Maratha commanders Raghunath Rao and Malhar Rao Holkar launched a major military campaign into Punjab.

- They expelled Abdali’s son Timur Shah and his general Jahan Khan from Lahore.

- Lahore, Attari, Peshawar, and Multan came under Maratha control.

- This marked the first time Marathas extended their power beyond the Indus River.

Strategic Importance

Control of Delhi and Punjab was not just a display of power but a strategic triumph. These regions could have served as a buffer zone against Afghan invasions if properly fortified. However, it was this expansion that alarmed Abdali and pushed him toward the Third Battle of Panipat.

Ahmed Shah Abdali’s Invasion of India

Ahmed Shah Abdali, also known as Ahmed Shah Durrani, was the founder of the Durrani Empire in Afghanistan. He rose as a powerful military commander under Nader Shah and became the ruler of Afghanistan in 1747 after Nader Shah’s assassination.

Abdali’s Multiple Invasions

Between 1748 and 1761, Abdali invaded India seven times. His goals included plundering India’s wealth, restoring Islamic influence, and maintaining dominance in northern India.

| Year | Campaign | Purpose / Result |

|---|---|---|

| 1748 | First Invasion | Exploiting instability after Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah’s death |

| 1750–51 | Second Campaign | To secure control over Punjab |

| 1757 | Delhi Attack | Looted Delhi and controlled the Mughal emperor |

| 1758 | Panjab Loss | Marathas expelled Abdali completely — became a turning point |

| 1760–61 | Final Invasion | Led to the decisive Third Battle of Panipat |

Maratha Challenge and Abdali’s Response

In 1758, the Marathas drove Afghan forces out of Punjab, Lahore, and Peshawar. For Abdali, this was a severe military and prestige setback. He believed that if the Marathas were not stopped, they would extend their rule to Kabul and Kandahar.

Najib-ud-Daula, the influential Rohilla chief of Delhi, invited Abdali to invade India.

With the support of Shuja-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Awadh, Abdali prepared a powerful Afghan–Indian alliance.

Abdali’s Strategy

- In 1760, Abdali crossed the Indus River and marched rapidly toward Delhi.

- He captured many regions across Haryana, Punjab, and western Uttar Pradesh.

- He cut off Maratha supply lines, weakening them before the battle.

Abdali’s aim was not just victory but establishing long-term influence and protecting Muslim powers from Maratha expansion.

Afghan–Rohilla–Shuja Alliance

When Abdali invaded India again in 1760, he was not alone. He aligned with powerful Indian groups threatened by the rise of the Maratha Empire. This alliance symbolized the complex religious, political, and strategic environment of 18th-century India.

1. Ahmed Shah Abdali (Afghan)

- Ruler of Afghanistan and committed to restoring Islamic influence in India.

- Maratha victory in Punjab threatened both his authority and strategic interests.

- He began uniting Muslim powers across the subcontinent.

2. Najib-ud-Daula (Rohilla Chief)

- A powerful Rohilla leader of Rohilkhand (present-day Uttar Pradesh).

- He had strong influence in Delhi and considered Maratha power a direct threat.

- He invited Abdali to invade India and promised local support.

“यदि आपने अभी हस्तक्षेप नहीं किया, तो सम्पूर्ण हिंदुस्तान मराठों के अधीन हो जाएगा।”

— Najib-ud-Daula to the Afghan court

3. Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh)

- Ruler of Awadh, a region of great strategic importance.

- Initially reluctant, but pressure from Abdali and fear of the Marathas forced him to join.

- He provided troops and financial support, strengthening the alliance.

Characteristics of the Alliance

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Religious Factor | Marathas were viewed as a rising Hindu power, motivating Muslim groups to unite. |

| Political Interest | Rohillas and Awadh did not want to be subdued by Maratha power. |

| Military Strength | Afghan cavalry + Rohilla infantry + Awadh’s support created an experienced joint army. |

Strategic Objectives

- To stop Maratha expansion in northern India

- To restore Islamic influence in Delhi

- To free Punjab and Doab from Maratha control

Impact of the Alliance

- The alliance was militarily powerful.

- It created a three-sided challenge for the Maratha army.

- This multi-centered alliance decisively challenged Maratha supremacy at Panipat.

Pre-War Situation

By the end of 1760, the atmosphere of northern India had become extremely tense, heavily burdened with the anticipation of a decisive war. The clash between the Maratha forces and Abdali's army was only a few steps away. Both sides had completed their preparations, yet circumstances, hunger, and strategic decisions made this war unique.

Maratha Advance into North India

Peshwa Balaji Bajirao sent his capable and brave cousin Sadashivrao Bhau with a massive army to North India.

- The army included more than 45,000 regular soldiers, heavy artillery, English-trained infantry (Gardi Brigade), and troops from allied Maratha chiefs.

- Vishwasrao, the Peshwa’s son, also accompanied Bhau — symbolically representing leadership.

The Maratha Plan

- Keep Abdali away from Delhi

- Destroy the influence of the Rohilla chiefs and Shuja-ud-Daula

- Protect the Mughal Emperor and retain control over Delhi

Supply Crisis and Strategic Mistakes

The Maratha army, although large and powerful, depended on long supply lines stretching hundreds of kilometers from Maharashtra.

- Local rulers and landowners in Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh refused to provide supplies, many already aligned with Abdali.

- The army returning from Punjab was exhausted and lacked local support.

Main Strategic Errors

- After taking Delhi, instead of strengthening their position, the Marathas camped at Panipat — a terrain favorable to Abdali.

- The army remained stationary for months without breaking enemy encirclement, leading to collapsing supplies, food, and morale.

- They underestimated Abdali’s mobility and the speed of his Afghan cavalry.

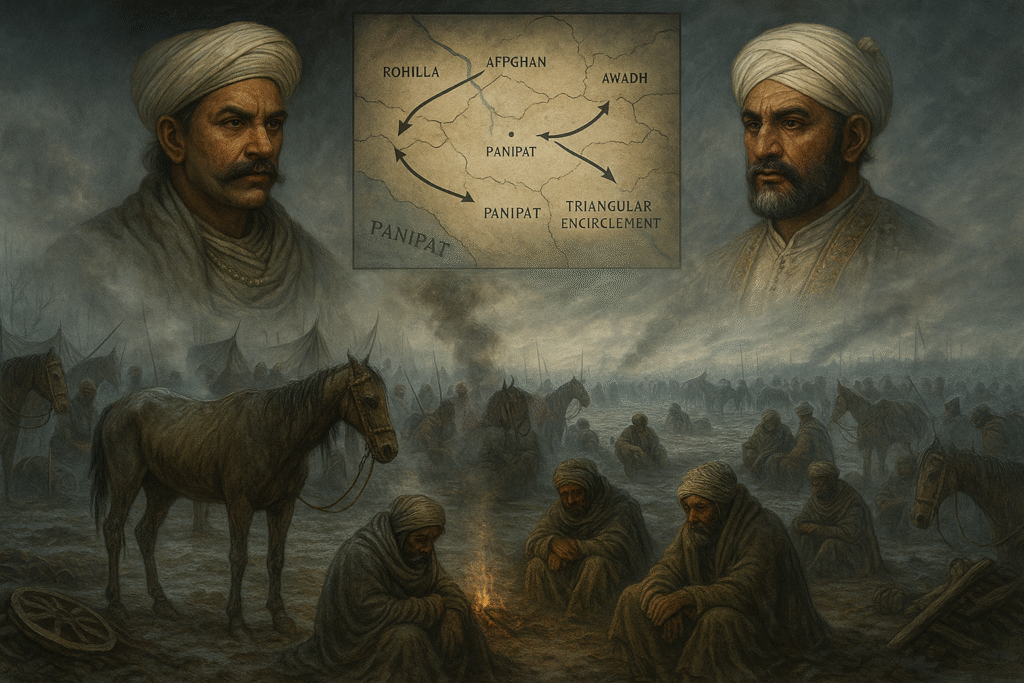

Abdali’s Encirclement Strategy

Ahmed Shah Abdali created a triangular encirclement to trap the static and exhausted Maratha forces:

- North-west: Abdali’s Afghan army

- East: Shuja-ud-Daula’s forces

- South-west: Najib-ud-Daula and Rohilla chiefs

This encirclement trapped the Marathas — no advance, no retreat.

Tense Stalemate

From October 1760 to January 1761, both armies remained face-to-face.

- Marathas suffered daily from shortages of food, fodder, and clothing.

- Bitter winter cold and diseases worsened conditions.

- Soldier morale collapsed, and internal disagreements surfaced.

Inevitability of Battle

As mid-January approached, the Marathas realized that they must either fight or die of starvation. Seeing Abdali’s army in a stronger position, Bhau ordered a decisive attack on 14 January 1761.

Conclusion

Before the war began, the Marathas were militarily strong but strategically weak. Lack of supplies, absence of local support, and Abdali’s clever encirclement forced them into a battle that was inevitable — and almost suicidal.

Supply and Strategic Mistakes

The downfall of the Marathas in the Third Battle of Panipat was largely due to logistical failures and strategic miscalculations. Although strong in numbers, artillery, and training, their geographical positioning, lack of local support, and poor long-term planning proved disastrous.

1. Extended Supply Lines

- The Maratha army was far from Maharashtra, relying on extremely long supply routes.

- Sending food, fodder, medicines, and weapons over this distance was difficult and slow.

- The Afghan-Rohilla alliance continuously disrupted these routes.

- Allied states like Jaipur and Jodhpur remained inactive due to their own political interests.

2. Lack of Local Support

- Local rulers and farmers of Haryana, Delhi, and Doab refused support due to Abdali’s pressure.

- Shuja-ud-Daula and Najib-ud-Daula blocked supply pathways.

- Locals viewed Marathas as “outsiders,” reducing political support.

3. Winter Encampment — A Fatal Mistake

- Marathas camped in the open plains near Panipat in December–January.

- No natural defenses such as hills, rivers, or forts.

- Cold, disease, and lack of nutrition killed thousands.

- Meanwhile, Abdali’s cavalry remained mobile and flexible.

4. Failure to Break Encirclement

- Abdali blocked the Marathas from three sides: Afghan cavalry (north), Shuja’s army (east), Rohillas (south).

- Supply lines collapsed, causing starvation, illness, and desertions.

- Some sources report 500+ deaths per day inside the Maratha camp.

5. Hastiness in Battle

- Sadashivrao Bhau wanted a short, decisive battle due to supply shortages.

- Abdali aimed to exhaust the Marathas through delay tactics.

- On 14 January 1761, the Marathas fought in a state of hunger, exhaustion, and despair — a suicidal choice.

Conclusion

The Maratha strategy failed due to poor battlefield selection, no local alliances, and ignoring supply chain requirements. Their military might was strong, but strategic and logistical errors destroyed a powerful empire.

Clashes at Kunjpura and Samalkha

Before the final battle at Panipat, two important clashes occurred between the Maratha and Abdali forces — the Battle of Kunjpura and the Skirmish at Samalkha. These encounters significantly shaped the final strategy and atmosphere before the decisive war.

Battle of Kunjpura (17 October 1760)

Location

Kunjpura (near Karnal, on the eastern bank of the Yamuna)

Main Forces

Maratha Army vs. Abdali’s Governor Nizam Khan’s forces

Background

Kunjpura was a strong fort selected by Abdali as a supply and communication center. It stored weapons, supplies, and soldiers. Sadashivrao Bhau identified it as a strategic target.

Conflict

- The Marathas surrounded the fort and captured it quickly on 17 October 1760.

- Nizam Khan was killed and many Afghans captured.

- The Marathas gained weapons, horses, food, and supplies, boosting morale temporarily.

Outcome

- A major tactical victory for the Marathas.

- But strategically a mistake — Kunjpura lay east of the Yamuna, while Abdali’s main army was west.

- Flooding of the Yamuna separated Bhau’s forces from their main camp.

Skirmish at Samalkha (November 1760)

Location

Samalkha (few kilometers south of Panipat)

Nature of the Clash

- A quick guerrilla-style skirmish, not a full battle.

- Abdali’s cavalry attacked Maratha supply convoys and seized provisions.

- Marathas retaliated but coordination was weak.

Strategic Importance

- Showed Abdali’s army preferred hit-and-run tactics.

- Revealed growing defensiveness and confusion within the Maratha forces.

Conclusion

The victory at Kunjpura was militarily impressive but strategically harmful, isolating the Marathas from their main forces. Meanwhile, the Samalkha clash revealed Abdali’s agile tactics and weakened the Marathas mentally and strategically. These events indicated that the upcoming battle would be decided not by numbers alone, but by speed, planning, and supply strength.

Third Battle of Panipat — Main Events, Strategies, and Decisive Turning Points

The Third Battle of Panipat was fought on 14 January 1761 on the plains of Panipat. Though the battle itself lasted a single day, months of preparation, maneuvering and attrition preceded it. The sequence of events on that day shattered Maratha ambitions in North India and reshaped the subcontinent’s political balance.

Morning: Opening of Battle

At dawn on 14 January the Maratha command, facing starvation and pressure to act, ordered the army forward. The Maratha field formation and leadership on the morning of battle were:

- Commanders: Sadashivrao Bhau (commander-in-chief) and Vishwasrao (Peshwa’s son) among key leaders.

- Formation: Three main echelons — (1) forward artillery and infantry, (2) heavy cavalry in the second line, (3) Sadashivrao Bhau with the massive supply and baggage train in the third.

This formation reflected the Marathas’ plan for a decisive clash: use artillery and disciplined infantry to break the Afghan front, then exploit with cavalry. However, the large baggage contingent and non-combatants with the army would complicate both mobility and resolve.

Midday: Attack and Early Response

- The Marathas initially pressed an aggressive attack. Ibrahim Gardi’s trained artillery and the infantry advanced and forced Abdali’s frontline to give ground.

- Vishwasrao’s personal bravery raised Maratha morale and briefly made victory seem possible.

- Tragically, Vishwasrao was killed in action; his death produced confusion and a sudden collapse of cohesion in the Maratha ranks.

Afternoon: Abdali’s Counter-Blow

- Abdali committed his reserve cavalry and Rohilla contingents, executing a pincer-like encirclement.

- Forces under Najib-ud-Daula and Shuja-ud-Daula attacked from the south and west, tightening the ring around Maratha formations.

- With supply lines already cut and troops exhausted, the Maratha front could not reform to meet the renewed pressure.

Evening: Collapse and Carnage

- By late afternoon and evening the Maratha army broke. Leadership was killed or scattered; Sadashivrao Bhau’s fate is still debated but he did not reconstitute command.

- Estimates indicate roughly ~70,000 Maratha military and civilian dead; thousands were captured and massacred in the aftermath.

- Widespread violence included the killing of combatants and civilians; contemporary sources record horrific slaughter of prisoners and non-combatants.

Estimated Casualties (approximate)

| Side | Estimated Forces | Estimated Casualties |

|---|---|---|

| Maratha | 45,000–60,000 | ~70,000 (military + civilians, in large-scale counts reported) |

| Abdali & Allies | 40,000–50,000 | ~15,000–20,000 |

“This battle was not only a clash of arms; it was the collision of two strategies — a brave, exhausted and starving army versus a cunning, mobile, and strategically prepared force.”

Conclusion — Immediate Lessons from the Battle Day

- The Third Battle of Panipat was not simply a tactical defeat for the Marathas — it was a strategic catastrophe that removed their dominance in North India.

- Maratha courage was undeniable, but strategic errors, logistical failure, and timely Afghan maneuvers determined the outcome.

Maratha Army: Organization and Strategy

1. Army Structure and Composition

- Commander: Sadashivrao Bhau

- Estimated strength: 45,000–60,000 soldiers

- Key components: Ibrahim Gardi’s artillery, cavalry contingents (Holkar, Scindia, Gaekwad elements), trained infantry, long baggage and supply trains, and accompanying civilian camp (families and dependants – reports indicate very large non-combatant numbers).

A critical operational weakness was that the Maratha column travelled with a vast civilian convoy — reportedly tens of thousands of non-combatants — which slowed movement and complicated wartime decision-making.

2. Principal Strategic Concept

- Maratha planning aimed at a short, decisive battle that would break Abdali’s army and secure Delhi.

- They emphasized artillery and disciplined infantry to punch the centre, then use cavalry exploitation.

- Field disposition: Ibrahim Gardi’s guns forward; centre with Bhau and Vishwasrao; rear housing logistic trains and non-combatants.

3. Strategic Weaknesses — Why the Plan Failed

Local support absent

- Key northern rulers (some Rajput chiefs, local zamindars and others) were not rallied to the Maratha cause — many were neutral, hostile, or coerced by Abdali.

Logistics and supply collapse

- Extended supply lines from Maharashtra over hundreds of kilometers were vulnerable and repeatedly cut by Abdali’s forces and allies.

- After the Kunjpura operation, Bhau’s main body became separated and supplies could not be reconnected reliably.

Unfamiliar theatre and climatic hardship

- Marathas lacked deep local knowledge of North India’s terrain and climate; winter hardships and disease eroded strength.

Presence of non-combat convoy

- The camp included women, children and baggage, making the army less flexible and prioritizing protection over maneuver.

4. Ibrahim Gardi’s Artillery — A Bright Spot

Ibrahim Gardi’s trained artillery and infantry performed well in the early phases, inflicting significant damage on Afghan front lines. But without sustained logistical support and cavalry superiority, this advantage could not be translated into lasting operational success.

5. Decisive Decision — Total Battle

After months of encirclement and shortages, Bhau opted for a single decisive battle — a “fight-to-the-end” choice. This do-or-die move either would bring victory or annihilation; tragically it became the latter.

Ahmad Shah Abdali — Strategy and Conduct

1. Strategic Aims

- Abdali’s goal was not necessarily to occupy India permanently but to stop Maratha expansion, secure Punjab and maintain Afghan influence.

- He sought to restore and uphold Muslim political influence around Delhi, while keeping ultimate control with his own power base.

2. Alliance Policy — “Divide & Exploit”

Abdali forged a coalition with local actors who feared Maratha dominance:

- Najib-ud-Daula (Rohilla chief) — local guide, source of manpower and intelligence.

- Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh) — substantial military contribution.

- Mughal Emperor (Shah Alam II) — symbolic legitimacy.

These alliances created a multi-front force that outmaneuvered the Maratha attempt to create a united Indian front.

3. Military Composition & Style

- Total force: ~40,000–50,000 soldiers (Afghan cavalry, Rohilla infantry and local allies).

- Distinctive attributes: highly mobile cavalry, skilled mounted archers, flexible raiding tactics and excellent local coordination via Rohilla and Awadh allies.

4. Core Tactical Features

- Encirclement (Attrition) Strategy: Abdali deliberately avoided a short, head-on contest. Instead he exhausted the Marathas — cut supply lines, delayed engagements, and weaponized winter deprivation.

- Feigns and Delay: He used false negotiations and delaying tactics to sap Maratha resolve and supplies.

- Hit-and-run & Cavalry Harassment: Mounted units repeatedly struck supply convoys, undermining logistics and morale.

5. Patience and Timing

Abdali’s greatest strength was strategic patience. He kept the Marathas immobile, let hunger and disease work against them, then struck decisively once the enemy was physically and psychologically broken.

Preceding Clashes: Kunjpura & Samalkha

Kunjpura (17 October 1760)

Location: Kunjpura, near Karnal on the Yamuna’s eastern bank.

Scenario: Kunjpura was a key Afghan supply and communication fort. Marathas attacked and captured it on 17 October 1760, killing Nizam Khan and seizing supplies, horses and ammunition.

Aftermath & Strategic Flaw: Although a tactical victory, Kunjpura lay east of the Yamuna while Abdali’s main force stood west. Monsoon or flood conditions and geography separated Bhau’s raiding contingent from his main army, complicating resupply and reunion.

Samalkha Skirmish (Nov 1760)

Type: Mobile skirmish south of Panipat.

- Abdali’s cavalry struck Maratha supply convoys and captured provisions.

- Marathas attempted to counter, but lack of coordination and clear direction prevented a decisive result.

These two engagements exposed a pattern: early Maratha success that failed to produce strategic advantage, while Abdali’s mobility and harassment steadily undermined the Maratha position.

Decisive Turning Points on 14 January 1761

1. Aggressive Maratha Opening

The morning offensive applied intense pressure: Ibrahim Gardi’s guns and trained infantry struck the Afghan lines and initially forced Abdali’s front backward.

2. Death of Vishwasrao — Psychological Shock

Mid-battle the Peshwa’s son Vishwasrao was killed by gunfire. This event shattered morale and command cohesion. Bhau’s decisions thereafter were affected by the shock and the urgent need to protect the camp and the families present.

3. Abdali’s Rear Assault

Abdali’s reserve forces launched a sudden rear and flank attack as Maratha lines weakened. This pincer consolidated the attritional effect and broke Maratha formations.

4. Logistics & Exhaustion

By afternoon, lack of food, water, ammunition, and rest left Maratha soldiers unable to sustain combat. Abdali’s forces continued pressure while local allies kept supply channels open to them.

5. Civilian Contingent Factor

Because a large non-combatant convoy accompanied the Marathas, many soldiers diverted attention to protecting families during retreat, further degrading military discipline.

6. Massacre & Aftermath

As the army disintegrated, Afghans and allies killed tens of thousands of combatants and civilians. Surviving Maratha power in Delhi and the north collapsed symbolically and practically.

Final Analysis — Why the Marathas Lost

- Poor strategic location and winter encampment in open plains.

- Extended and vulnerable supply lines severed by coordinated Afghan-Rohilla actions.

- Lack of a unified indigenous coalition against Abdali.

- Overburdened army slowed by a massive baggage and civilian contingent.

- Abdali’s strategic patience, mobility, and superior encirclement tactics.

Closing Thoughts

The Third Battle of Panipat remains one of the most consequential battles on the subcontinent. It combined operational and logistical failures on the Maratha side with political savvy and tactical patience on Abdali’s. The day’s tragic toll and long-term political consequences made Panipat a watershed: an example of how logistics, alliances and strategic timing can decide destiny as surely as courage and numbers.

Consequences of the Third Battle of Panipat

Fought on 14 January 1761, the Third Battle of Panipat was one of the most decisive and devastating conflicts in Indian history. Its consequences reshaped the political landscape of the subcontinent — not only crippling the Maratha power but also creating conditions that eased the later expansion of the British East India Company.

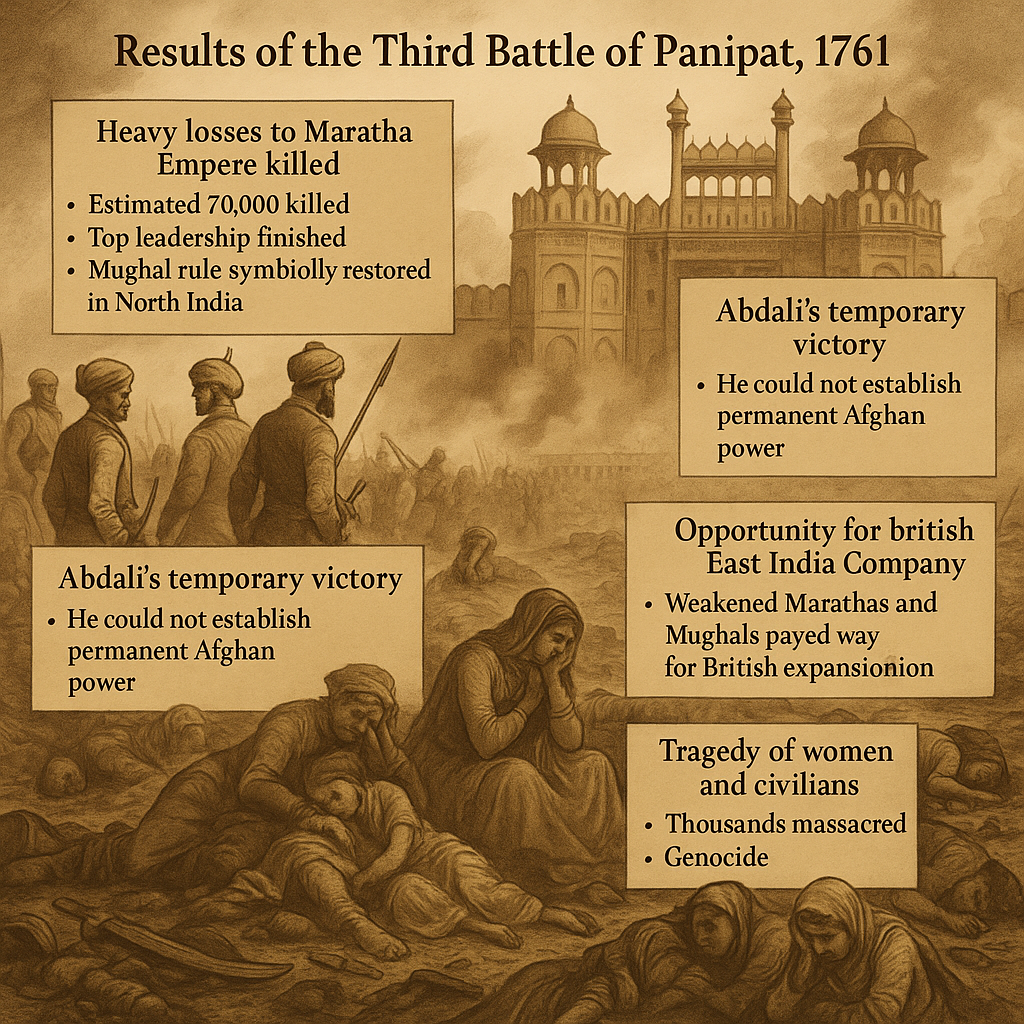

1. Heavy Losses to the Maratha Empire

- Estimated ~70,000 Maratha soldiers and many civilians were killed during the battle and subsequent massacres.

- Top leaders such as Sadashivrao Bhau and Vishwasrao were lost, creating a leadership vacuum.

- Major chiefs (Holkar, Scindia, Bhonsle factions) were scattered and demoralized.

- The Maratha polity became politically and militarily crippled in the immediate aftermath.

2. End of Maratha Control over Delhi

- Before Panipat, Marathas had effectively become the real power in Delhi; Panipat ended that dominance.

- Ahmed Shah Abdali installed Shah Alam II as a symbolic ruler, though effective control remained fractured.

- A political vacuum opened across North India after the battle.

3. Abdali’s Temporary Victory

- Although Abdali won the battle, he did not establish long-term administration over India.

- He held sway over parts of Punjab and Delhi for a short period, but returned home rather than attempting permanent rule.

- Abdali’s victory was strategically significant but not institutionally lasting.

4. Opportunity for the British East India Company

- Maratha weakness and Mughal decline cleared space for British expansion in the following decades.

- The Battle of Buxar (1764) and subsequent British interventions accelerated colonial consolidation.

- Panipat symbolized the disunity of indigenous powers and the opening for foreign political influence.

5. Psychological Shock in Indian Politics

- The Marathas’ confidence suffered a deep blow; a sense of shock and despair spread across many regions.

- The widespread perception grew that Indian powers could not unite effectively against external threats.

- This morale crisis eroded coordinated resistance to future European interventions.

6. Civilian Tragedy and Human Cost

- Thousands of non-combatants — women, children, camp followers — suffered captivity, massacre, or displacement.

- The battle became emblematic of mass civilian suffering and has been remembered in songs, poetry and local memory as a catastrophe.

7. The Beginning of Maratha Recovery (Long-Term Outcome)

- Despite the catastrophic defeat, Maratha power gradually revived over the next decade under leaders like Mahadji Sindhia.

- Maratha influence re-emerged in parts of North India, but their revival came at the cost of leaving the subcontinent vulnerable to rising British power.

- Ultimately, the Marathas’ recovery represented the last major indigenous attempt to reassert power before extensive British dominance.

Conclusion

The Third Battle of Panipat was more than a military defeat for the Marathas — it was a political earthquake that exposed the limits of unified indigenous resistance and opened the subcontinent to new foreign influence. The battle’s human cost, political fragmentation, and the temporary power shifts it triggered marked a turning point that helped shape the path toward colonial consolidation.

Historical Significance and Legacy of the Third Battle of Panipat

The Third Battle of Panipat (14 January 1761) was not only a clash of armies but a turning point that shook the foundations of power, politics, and culture in the Indian subcontinent. Its legacy continues to hold deep relevance for historians, political thinkers, and India’s modern nation-building journey.

1. A Symbol of the Failure of National Unity

- The battle highlights how disunity among Indian powers repeatedly benefited foreign invaders.

- Despite their strength, the Marathas failed to secure alliances with Rajputs, Nawabs, and Sikhs in North India.

- History echoed one painful truth — “India’s weakness lay in India’s fragmented politics.”

2. The Final Attempt to Restore Power Balance

- The battle marked the Maratha Empire’s last major attempt to dominate Delhi and North India politically.

- It stands as a dividing line between the declining Mughal era and the emerging British colonial period.

3. A Gateway for British Colonial Expansion

- After Panipat, traditional Indian powers were too weakened to resist the British East India Company.

- The absence of a unified Indian power allowed the Company to expand militarily and politically.

- The battle effectively became the doorway through which the colonial era entered India.

4. Collective Memory and Cultural Impact

- The battle lives on not only in historical records but in Marathi literature, folk songs, and Indo-Persian chronicles.

- Names like Sadashivrao Bhau and Ahmed Shah Abdali remain powerful symbols of bravery and brutality.

- The soil of Panipat still holds memorials and mass graves that silently narrate the tragedy.

5. Military Strategy Lessons for the Future

- The battle offers rare insights into logistics, alliance-building, geopolitics, and the ethics of warfare.

- Pre-war strategic failures — poor supplies, weak alliances, and unfamiliar geography — are still studied in military academies.

- Panipat stands as a real case study demonstrating how strategy can outweigh sheer numbers.

6. Remembered as a Legacy of Warning

- The battle reminds us that power and numbers alone do not guarantee victory — unity, vision, and timely decisions matter far more.

- Even in the modern era, Panipat warns India that regionalism, fragmentation, and narrow politics can endanger national sovereignty.

Conclusion

The Third Battle of Panipat is not only a story of defeat — it is a lasting reflection of India’s national consciousness. Its legacy teaches that history is more than a chronicle of events; it is a mirror that shapes the destiny of nations.

Conclusion – The Greatest Warning of History

The Third Battle of Panipat (14 January 1761) was not only one of the most devastating battles in Indian military history, but also a living example of political instability, strategic miscalculations, and the absence of united national leadership. The defeat of the Marathas was not merely a military loss—it marked the collapse of an indigenous empire’s grand ambition and opened the doors for the rise of foreign dominance in India.

This battle made it clear that strength or bravery alone is not enough—harmony, foresight, and political unity are equally essential for nation-building. The political vacuum created after the war became the gateway for the British East India Company’s rise as the dominant power in India.

Today, the legacy of the Third Battle of Panipat reminds us that internal divisions, untimely decisions, and the lack of cooperation make any nation vulnerable to external interference. This battle is recorded in history as a warning —

Final Thoughts

The land of Panipat witnessed bloodshed and sacrifice not merely as a chapter of history, but as a solemn reminder for the nation. From this war, we must learn not only strategy but also the spirit of unity for national interest.

References

- Jadunath Sarkar – Fall of the Mughal Empire (Vol. II & III)

A highly reliable English source analyzing the Marathas, Abdali, and the depth of the Panipat conflict. - Raghunath Rai – History of Modern India

A credible work analyzing the political and social background of the war. - Surendra Nath Sen – Administrative System of the Marathas

Focuses on the administrative and strategic structure of Maratha power. - Govind Sakharam Sardesai – New History of the Marathas (Vol. II)

A detailed analysis of Maratha expansion, especially in North India, and their role in the Panipat war. - Irfan Habib – Medieval India: The Study of a Civilization

A modern review of political alliances, imperial conflicts, and religious dynamics. - Dr. Vishwas Patil – Panipat (Marathi Novel)

A literary-historical narrative exploring human and strategic dimensions of the battle. - Cambridge History of India – Volume V: The Indian Empire

Academic compilation covering British and pre-Mughal India. - Primary Persian Sources – Tarikh-i-Ahmad Shahi & Maasir-ul-Umara

First-hand historical records by Abdali’s chroniclers and Mughal historians. - NCERT – Themes in Indian History (Class XII)

A standard educational source providing factual and simplified perspectives. - Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)

Archaeological and geographical evidence from Panipat war memorials and sites.