Introduction and Background

The year 1927 stands as a turning point in the history of India’s freedom struggle. It was a period marked by rising political awareness, growing national consciousness, and increasing dissatisfaction with British colonial policies. In the years following the First World War, the British Empire was facing administrative pressures and economic challenges, while India was witnessing a surge of national movements. Within this turbulent environment, the British government decided to send a special commission to review the constitutional framework and administrative structure of India. This commission came to be known as the Simon Commission of 1927.

The formation of this commission was expected to be a significant milestone for India’s political future. It was intended to evaluate the working of the Government of India Act of 1919 and recommend further reforms. However, from the very beginning, the composition of the commission revealed a troubling truth: not a single Indian was included in the body that was supposed to decide the direction of India’s political development. This exclusion was viewed as a direct insult to India’s demand for self-governance, and it quickly transformed the commission from an administrative initiative into a symbol of colonial arrogance.

What Was the Simon Commission?

The Simon Commission, officially known as the Indian Statutory Commission, consisted of seven British Members of Parliament and was chaired by Sir John Simon. Its stated purpose was to assess the functioning of the diarchy system introduced by the 1919 Act and to propose administrative recommendations for India’s future governance. However, the absence of Indian representation made it clear that the British government was unwilling to grant India meaningful participation in shaping its own constitutional reforms.

The Political Climate in India

To understand the reaction to the Simon Commission, it is essential to look at the political landscape of India in the 1920s. The Non-Cooperation Movement, launched by Mahatma Gandhi, had awakened the masses and expanded the idea of Swaraj—self-rule—across the nation. Political organizations, youth groups, student bodies, and regional movements had become more organized and assertive. The demand for greater Indian involvement in governance was louder than ever.

The British government, alarmed by this rising national consciousness, hoped to delay substantial reforms by appointing the Simon Commission ahead of schedule. What they expected to be a political maneuver, however, turned into an unexpected crisis, as Indian leaders of all ideologies came together in opposition to the commission. Once it became known that the commission included only British members, national outrage spread rapidly.

The Crisis of Representation

The exclusion of Indians from the commission was more than a political oversight—it was a fundamental denial of India's demand for representation. For a country striving for self-determination, this decision was seen as a deliberate attempt to undermine Indian aspirations. The immediate response was widespread condemnation from political parties, media, regional organizations, and the public.

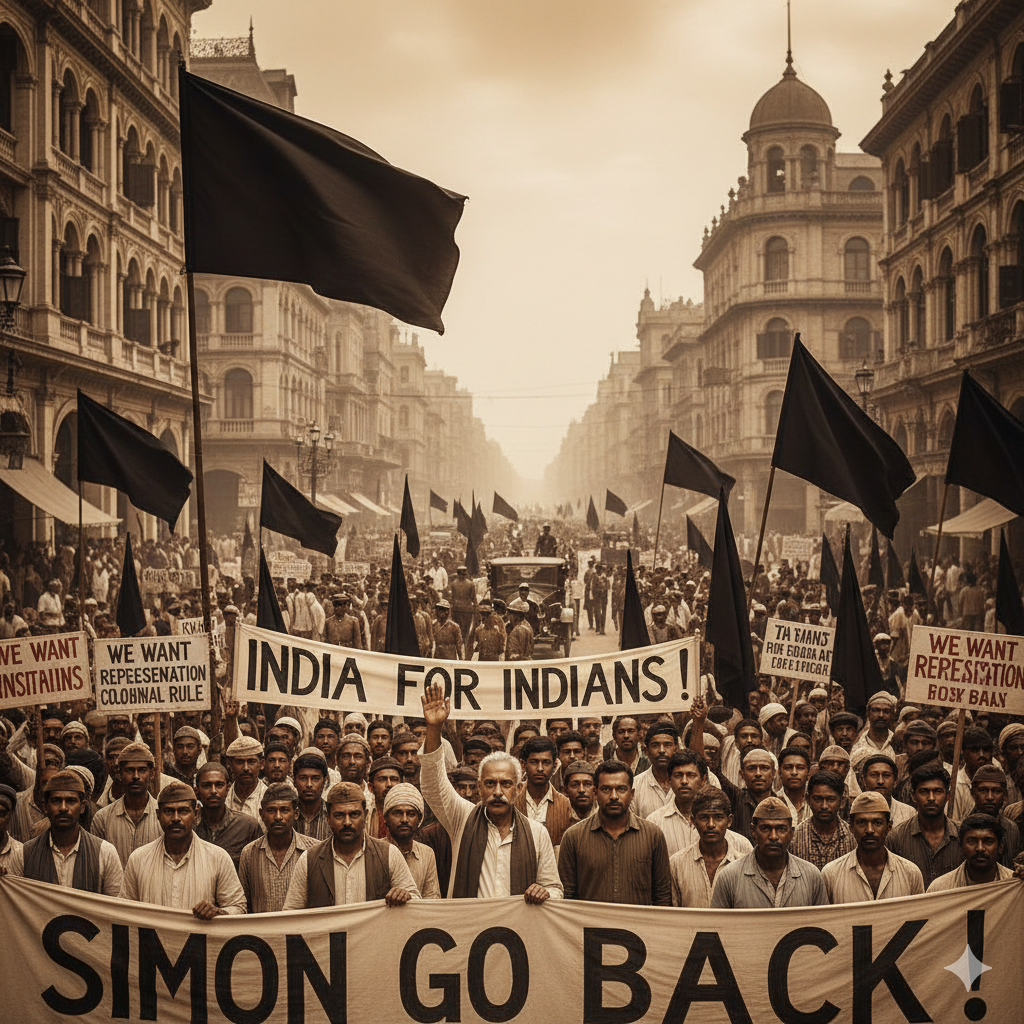

When the commission arrived in India, it was met not with acceptance but with unprecedented national resistance. People filled the streets with black flags, chanting the now famous slogan “Simon Go Back!”. Students, lawyers, workers, and leaders from across the country united in protest. This moment marked one of the rare phases in the freedom movement where diverse political groups—Congress, liberals, socialists, and even some communal organizations— stood together in collective opposition.

Thus, the Simon Commission of 1927 became far more than a statutory committee. It became a catalyst for national unity, a symbol of India’s refusal to accept reforms imposed without consultation, and a spark that intensified the demand for complete independence. The events surrounding the commission laid the foundation for future movements, including the Civil Disobedience Movement and the eventual call for Purna Swaraj—complete independence. The episode demonstrated that India was no longer willing to be a passive observer in its political destiny; it was prepared to shape its own future.

Personal Beginning — My Story

My connection with history began long before I understood its importance. As a child, I would often sit beside my grandfather on quiet evenings when he narrated tales from India’s freedom struggle. His voice carried a certain depth, as if he had lived through those moments himself. Among the many stories he shared, one name echoed repeatedly — the Simon Commission. I remember wondering why this single event had left such a deep mark on the collective memory of our nation. Why did an entire country shout “Simon Go Back!” in one voice? Years later, this question became the beginning of my own journey into understanding the significance of the Simon Commission of 1927.

My curiosity deepened the day I came across an old black-and-white picture in a history book. It showed thousands of people standing with black flags raised high, their faces filled with anger, determination, and a shared sense of injustice. For a few moments, I stared at the image without turning the page. It was not just a protest; it was emotion, courage, and unity frozen in time. Even though I was separated from that era by nearly a century, something in that photograph connected with me deeply. I felt the frustration of those people, the fearlessness of their voices, and their dream for a free nation.

The Beginning of My Curiosity

Years later, during college, my history professor made a statement that stayed with me forever: “The Simon Commission was not merely a political misstep — it was a moment when Indians realized that they must decide their own future.” That sentence pierced through my thoughts. What was it about the commission that awakened such powerful emotions across the country? I decided that day that I would dig deeper, explore old documents, and understand not only the event but also the people who lived it.

As I read more, I realized that the core issue was not merely the commission itself, but the complete lack of Indian representation. The British government wished to assess India’s political needs without including a single Indian in the decision-making body. This felt deeply wrong to me. How could a nation’s future be planned without listening to its own people? And that very thought made me understand why the protest wasn’t just political — it was personal, emotional, and symbolic.

A Newspaper That Changed My Perspective

One afternoon in the library, while searching through archived materials, I stumbled upon an old newspaper from 1928. Its headline read: “India Will Not Welcome the Simon Commission.” Just below it was a short column describing a student protest. The article explained how students shut their colleges, marched with black flags, and raised slogans against the commission. What struck me most was a quoted statement from one of those young protesters:

“We come to college to learn, but today we have learned something bigger — our future must be shaped by our own hands, not by a foreign power.”

This single sentence shook something inside me. It made me realize that history is not made solely by politicians or great leaders. It is also written by ordinary people — students, workers, women, and citizens who refuse to remain silent when their rights are denied. That student’s voice became a bridge between the past and my own understanding of freedom, responsibility, and courage.

An Emotional Image I Will Never Forget

During my research, I found another picture — one that I still remember vividly. It showed an elderly woman standing with her young son, both holding black flags. She was not a political leader, nor was she mentioned in any official record. Yet, the determination in her eyes told an entire story. She represented thousands of unnamed Indians whose courage fueled the movement.

In that moment, I felt as if she was speaking to me through time: “Do not just read history; understand why we raised our voices. We stood so that you could stand freely today.” Her silent message made the Simon Commission protest come alive in my heart — not as an event, but as a lesson.

What This Journey Taught Me

Through my exploration, I realized that the Simon Commission was not just about political reforms. It was about dignity, representation, and self-respect. The protests reminded me that a nation grows stronger when its people stand together and demand rightful participation. Representation is not a privilege; it is a basic democratic right. The unity that emerged during the Simon Commission protests showed that when a society rises as one, no empire is strong enough to silence it.

Today, as I write this story, I feel a deep sense of connection with the past. History is not a collection of dates or events — it is a living narrative that shapes our identity. The Simon Commission protest is not just a page from 1927; it is a reminder of India’s spirit of unity and self-belief.

Even now, whenever I read the words “Simon Go Back,” I feel an energy rise within me — the same energy that once united millions. It reminds me that the strength of any nation lies not in its rulers, but in its people — their courage, their dreams, and their determination to shape their own destiny.

Timeline of Events (1927–1929)

The story of the Simon Commission is not just the introduction of an administrative committee but a defining chapter in India’s struggle for independence. Between 1927 and 1929, the arrival of the commission, the unprecedented protests against it, and the political consequences that followed helped shape India’s constitutional and national movement in significant ways. The following timeline presents a clear, event-wise understanding of how a single commission triggered a nationwide awakening.

1927: Announcement and Early Reactions

In 1927, the British government announced the formation of a Statutory Commission to review the working of the Government of India Act of 1919. Although the Act had mandated that such a commission be appointed ten years later, it was set up earlier due to administrative concerns and rising political pressures in India. The commission was chaired by Sir John Simon and included seven British Members of Parliament.

However, the initial excitement faded quickly when Indians learned that the commission did not include a single Indian member. This exclusion was perceived as a direct challenge to India’s demand for self-representation. The decision insulted not just political leaders, but the people of India who believed that reforms without Indian involvement could never be legitimate or meaningful. As a result, criticism began pouring in from across the nation even before the commission set foot on Indian soil.

1928: Arrival of the Commission and the Wave of Protests

In February 1928, when the Simon Commission arrived in India, it was greeted not with acceptance but with one of the largest protests the country had ever witnessed. Political parties with differing ideologies came together in a rare moment of unity. People across cities shouted the powerful slogan “Simon Go Back!” and raised black flags to show their collective rejection of the commission.

As the commission traveled through major cities such as Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Lahore, and Delhi, the intensity of protests continued to rise. It faced strong public anger wherever it went. In several cities, the commission had to move under heavy police protection because the crowds were too large and too determined to be ignored.

Lahore: The Peak of Protests and the Death of Lala Lajpat Rai

One of the most dramatic and tragic events occurred on 30 October 1928 in Lahore. A massive protest rally was organized against the Simon Commission, led by the beloved nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai, also known as the "Punjab Kesari." To disperse the peaceful protest, the British police ordered a brutal lathi charge. Lajpat Rai was severely injured during this attack and succumbed to his injuries a few weeks later.

His death shook the entire nation. It ignited a wave of outrage and motivated young revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru to take decisive action. This incident intensified the freedom struggle and made the Simon Commission a symbol of colonial oppression.

1929: Final Report and Its Impact

In 1929, the Simon Commission submitted its final report to the British Parliament. Although it recommended certain administrative reforms, including an expansion of provincial autonomy, it failed to address the central demand of Indians: full self-governance and genuine political representation. As expected, Indian leadership denounced the report as incomplete, biased, and disconnected from India’s real needs.

In response to the commission, Indian leaders had already prepared their own constitutional framework in 1928 — the Nehru Report, drafted under the leadership of Motilal Nehru. This report outlined a vision of self-governance by Indians themselves and stood as a direct counter to the Simon Commission’s recommendations.

Timeline — Key Events (Summary)

- 1927: Simon Commission announced; widespread dissatisfaction begins.

- February 1928: Commission arrives in India; massive protests and “Simon Go Back!” slogan.

- October 1928: Lahore protests; brutal lathi charge injures Lala Lajpat Rai.

- November 1928: Lala Lajpat Rai passes away; nation reacts with fury.

- 1929: Commission submits its final report; Indian leadership rejects it.

Thus, the events from 1927 to 1929 surrounding the Simon Commission transformed the political landscape of India. The protests were not merely against a commission, but against the denial of representation and the arrogance of colonial rule. The timeline of these events reminds us that when a nation unites in its demand for justice and dignity, its voice becomes powerful enough to change the course of history.

Key Personalities

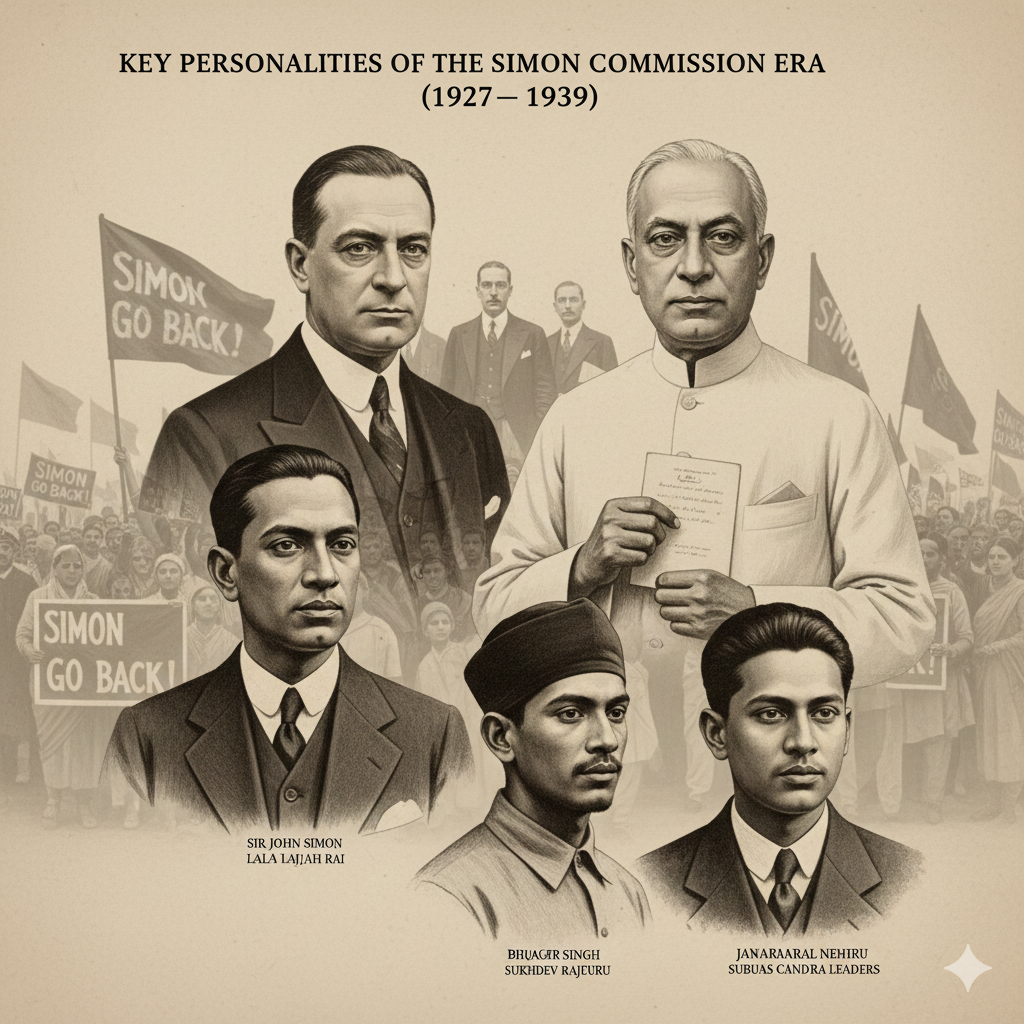

The Simon Commission of 1927 brought several important national leaders and revolutionaries to the forefront of India’s freedom movement. While the commission itself consisted entirely of British members, the strong resistance against it highlighted the presence of powerful Indian voices who refused to accept reforms without representation. This section introduces the major personalities whose roles shaped the political and emotional landscape of the Simon Commission era.

Sir John Simon — Chairman of the Commission

Sir John Simon, a prominent British politician, served as the chairman of the Simon Commission. Although he had a reputation for being a capable statesman, his leadership of a commission that excluded all Indian representation made him a controversial figure in India. Despite the official aim of reviewing constitutional progress, Indians viewed Simon as a symbol of colonial arrogance. Wherever he traveled during the commission’s tour of India, he faced intense public anger and was greeted with black flags and loud cries of “Simon Go Back!”.

Lala Lajpat Rai — The Symbol of Resistance

Among the strongest voices opposing the commission was the legendary freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai, also known as the “Lion of Punjab.” In Lahore, on 30 October 1928, he led a massive peaceful protest against the arrival of the commission. The British police ordered a brutal lathi charge to disperse the demonstrators, and Lajpat Rai was severely injured. He succumbed to his injuries a few weeks later. His death sent shockwaves across the nation and transformed him into a martyr of the freedom struggle. His sacrifice intensified the spirit of resistance and inspired countless Indians to join the movement.

Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru — The Young Revolutionaries

The death of Lala Lajpat Rai had a profound impact on young revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru. Angered by the injustice, they vowed to avenge his death. Believing that the British officer responsible for the lathi charge must be punished, the young revolutionaries shot Assistant Superintendent John Saunders. This daring act was a defining moment in the revolutionary movement and showcased the determination of India’s youth to fight colonial oppression.

Motilal Nehru — Architect of India’s Response

One of the strongest intellectual and political responses to the Simon Commission came from Motilal Nehru. Deeply dissatisfied with the commission’s exclusion of Indians, he led the drafting of the Nehru Report in 1928. It was the first major Indian attempt to outline a constitutional framework for self-governance. The report not only criticized the Simon Commission but also presented a clear alternative vision for India’s political future. Motilal Nehru’s work demonstrated that India was fully capable of shaping its own path without foreign intervention.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose — The Voice of Youth

The arrival of the Simon Commission also energized India’s young leadership. Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose were among the most vocal critics of the commission. Both leaders emphasized that India no longer desired partial reforms but demanded complete independence. Their speeches, writings, and public mobilization efforts helped unite students, workers, and ordinary citizens against the commission. Their involvement signaled a generational shift in the national movement, with younger leaders taking a more assertive stance.

The Indian Public — The True Power of the Movement

While leaders played vital roles, the true force behind the Simon Commission protests was the Indian public. Ordinary citizens from villages, towns, and cities came out carrying black flags, raising slogans, and expressing their resentment against a commission that denied them representation. Students boycotted classes, lawyers abandoned courts, workers joined strikes, and women participated fearlessly in street demonstrations. Their collective strength transformed the protest into a national awakening.

Together, these personalities — leaders, revolutionaries and common citizens — turned the movement against the Simon Commission into a symbol of India’s unity, self-respect, and resolve. Their actions proved that leadership is not limited to political positions, but emerges from the collective consciousness of a determined nation.

Reactions in India: Protests and Movements

The arrival of the Simon Commission in 1927–1928 triggered one of the most powerful and unified protest movements in India’s freedom struggle. For the first time, people across regions, communities, social classes, and political groups came together to oppose a decision imposed without Indian consent. The protests were not merely political; they were an emotional and symbolic rejection of colonial authority. The entire nation made it clear that it would not accept constitutional reforms without Indian representation.

Beginning of Nationwide Dissatisfaction

The moment Indians learned that the commission included no Indian members, a deep wave of anger began to sweep across the country. It raised a fundamental question: “How can decisions about India be made without Indians themselves?” This sentiment created unprecedented unity across the political spectrum. The Indian National Congress announced a complete boycott of the commission, soon followed by many other political groups including a large faction of the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha, worker unions, and student groups. For the first time, different ideologies stood together for a common cause.

The Commission’s Tour and the Public Uprising

When the Simon Commission landed in Bombay in February 1928, it was welcomed not with ceremony but with massive gatherings of people holding black flags. The streets echoed with the resounding slogan “Simon Go Back!”, which soon became the symbol of the movement. It was not just a protest slogan; it was the voice of millions expressing their desire for dignity, self-respect, and rightful participation in governance.

As the commission traveled through major cities such as Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Lahore, and Delhi, the protests only intensified. In every city, huge demonstrations blocked their path. The commission had to move under tight police protection. The message was clear: India would no longer tolerate reforms dictated by an external power.

Lahore: The Peak of the Protest Movement

The most defining moment in the anti-Simon protest occurred on 30 October 1928 in Lahore. A massive non-violent demonstration was organized under the leadership of Lala Lajpat Rai, the iconic freedom fighter known as the “Lion of Punjab.” Thousands marched peacefully, but the British police responded with a brutal lathi charge.

Lala Lajpat Rai was severely injured in the attack. Before collapsing, he delivered the unforgettable words:

“Every blow on my body will be a nail in the coffin of British rule in India.”

A few weeks later, he succumbed to his injuries. His death shocked the entire nation and transformed him into a martyr of the movement. The tragedy ignited the spirit of resistance among millions of Indians and especially among the young revolutionaries.

The Rise of Revolutionary Spirit

Lala Lajpat Rai’s death deeply impacted the youth. Revolutionaries such as Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru believed that the violence inflicted upon a respected national leader could not go unanswered. In retaliation, they assassinated Assistant Superintendent John Saunders, whom they held responsible for ordering the lathi charge. This act marked a new phase of revolutionary intensity and strengthened the resolve of the people to challenge colonial injustice.

Students, Women, and Ordinary Citizens — The Backbone of the Movement

Students played a crucial role in mobilizing the masses. Colleges across the country witnessed widespread strikes, boycotts, and marches. Student leaders organized rallies and street demonstrations, creating an environment where young people actively shaped political discourse. Their involvement made the movement vibrant and deeply connected with the youth of India.

Women, too, emerged as powerful participants. They marched in protests, raised black flags, and openly challenged colonial authority. Their presence in the movement showed that the struggle for freedom was not confined to men—it was a collective effort involving the entire nation.

The Role of Press and Literature

The Indian press became a crucial force in amplifying the protests. Newspapers published editorials criticizing the commission, highlighted public grievances, and exposed British injustice. Many editors faced heavy fines, suppression, and imprisonment, yet they continued their fearless reporting.

Writers and poets also contributed significantly by capturing the emotions of the movement through powerful words. Their writings helped ignite nationalism and united people far beyond the protest sites.

In essence, the reaction to the Simon Commission evolved into a massive national awakening. It was not just a protest against a single commission but a clear declaration that India would no longer accept governance without representation. The movement strengthened the spirit of unity, self-respect, and determination—qualities that became central to India’s journey toward freedom.

Analysis: What Went Wrong with the Simon Commission?

The Simon Commission, established in 1927 to evaluate the constitutional reforms introduced under the Government of India Act of 1919, remains one of the most controversial political decisions of British rule in India. Although intended to assess administrative progress, the commission ended up igniting widespread anger and resistance. Understanding what went wrong with the Simon Commission requires an examination of its political, administrative, social, and psychological shortcomings. This section explores why the commission failed even before it began its work, and how these failures reshaped India’s national movement.

1. Complete Absence of Indian Representation — The Fundamental Mistake

The most glaring and unforgivable flaw of the Simon Commission was that it included no Indian members. At a time when India’s political consciousness was rapidly evolving and nationalist movements were gaining strength, the exclusion of Indians from a committee reviewing India’s future was seen as a direct insult. By 1927, Indians believed not only in self-rule but also in the principle that any constitutional reform must involve the people it aims to govern.

This absence of representation made the commission appear arrogant and dismissive. It sent a clear message that the British government did not trust the capability of Indians to participate in shaping their own political system. As a result, public distrust began even before the commission set foot in India.

2. Misreading India’s Political Climate

One of the major reasons for the commission’s failure was the British government’s complete miscalculation of India’s political landscape. The 1920s were marked by the rise of mass movements, particularly after the Non-Cooperation Movement. People across the country were politically aware, socially mobilized, and ready to challenge unjust colonial decisions.

British officials underestimated this awakened nationalism and assumed that Indians would accept the commission simply because it was a constitutional requirement. They did not consider the emotional and political transformation that had occurred in the country. By ignoring the ground reality, the commission effectively alienated every major political group in India.

3. Lack of Cultural Understanding and Social Sensitivity

Members of the Simon Commission were experienced British politicians, but they lacked understanding of India’s cultural diversity, societal complexities, and administrative challenges. They did not speak Indian languages, were unfamiliar with regional issues, and had limited insight into the daily struggles of ordinary Indians.

India is a nation of many religions, languages, castes, and regions, and administering it requires not just political knowledge, but cultural sensitivity. The commission’s approach was purely administrative and did not account for India’s emotional, social, and psychological realities. This widened the gap between the British officials and the Indian masses.

4. Psychological and Emotional Disconnect with the People

The arrival of the Simon Commission touched a deeper emotional chord in India. For the people, this was not simply about reforms — it was about dignity, identity, and self-respect. Indians wanted a voice in shaping their own destiny. When the commission arrived without Indian representation, it symbolized continued British dominance and disregard for Indian aspirations.

The British government failed to grasp the emotional significance of the moment. They believed Indians would protest mildly and eventually accept the commission. Instead, the protests grew into a national movement. The resentment was not about administrative clauses — it was about being denied equality and the right to participate in governance.

5. Better Alternatives Existed — But Were Ignored

One of the greatest tragedies of the Simon Commission was that the British had several better options available to them, yet they chose the most insensitive one. For instance:

- They could have included respected Indian leaders in the commission.

- They could have consulted major political groups before forming it.

- They could have created a joint British-Indian committee to build trust.

- They could have ensured regional representation to reflect India’s diversity.

Had even one of these steps been taken, the commission would likely have gained more legitimacy. However, the British government’s rigid attitude and refusal to adapt made the commission destined to fail.

Conclusion: A Failed Commission, But a Stronger India

The Simon Commission failed because it ignored the basic democratic principles of representation, consultation, and respect for the people it aimed to govern. But ironically, its failure strengthened India’s fight for independence. The widespread protests that followed united Indians like never before, inspiring movements that eventually led to the demand for Purna Swaraj — complete independence.

In hindsight, the failure of the Simon Commission was not merely an administrative mistake. It was a turning point that awakened political consciousness, encouraged unity, and reaffirmed India’s determination to shape its own destiny. Thus, the commission’s failure became India’s moral and political victory.

Legacy and Modern Lessons

The story of the Simon Commission is not just a historical episode but a powerful turning point that shaped India’s political consciousness. Between 1927 and 1929, the commission’s arrival, the nationwide protests, and the rise of constitutional awareness created long-lasting effects on India’s freedom struggle. Its legacy continues to influence modern India, especially in matters related to democracy, representation, and civic participation. This section explores what the Simon Commission left behind and what lessons the modern world can learn from it.

1. The Principle of Representation — Foundation of Democracy

The Simon Commission’s biggest flaw — the complete absence of Indian members — taught India one of its most important political lessons: that governance without representation is both unjust and unacceptable. This idea became the moral foundation of India’s democratic future.

Today’s Indian political structure, from panchayats to the Parliament, is built on this principle. The commission’s rejection demonstrated that people will not accept decisions that exclude their voices. In modern democratic systems, meaningful participation and public consultation are considered essential components of responsible governance.

2. A Historic Example of National Unity

One of the most profound legacies of the anti-Simon movement was the unprecedented unity it created. The Indian National Congress, Muslim League factions, Hindu Mahasabha, student groups, trade unions — all stood together against the commission. This moment of unity sent a strong message that when national interest is at stake, divisions of ideology, region, or religion become secondary.

The movement highlighted the power of collective voice. Modern India, which faces numerous social and political challenges, continues to draw strength from this example. It reminds us that progress is possible only when diverse communities collaborate for a shared goal.

3. Growth of Constitutional Awareness and Political Confidence

The rejection of the Simon Commission pushed Indian leaders to create their own constitutional blueprint. This led to the drafting of the Nehru Report (1928), led by Motilal Nehru — the first comprehensive Indian proposal for self-governance.

This step demonstrated India’s ability to envision and design a modern political structure. It marked the beginning of constitutional self-reliance, which ultimately paved the way for the framing of the Indian Constitution. The episode increased political confidence and showcased that Indians were fully capable of shaping their own democratic future.

4. The Democratic Value of Protest and Dissent

The protests against the Simon Commission highlighted the importance of dissent in a democratic society. People from all walks of life — students, workers, lawyers, women, and ordinary citizens — openly challenged the British government’s decisions.

These demonstrations strengthened India’s civic culture and normalized public participation in political processes. In modern times, this principle remains relevant. Democracies thrive when citizens have the freedom to question authority, express disagreement, and demand accountability.

5. A Lesson in Self-Respect and Self-Determination

The failure of the Simon Commission also taught India that reforms are meaningful only when they uphold dignity and self-determination. Indians realized that limited or externally imposed reforms would never satisfy their aspirations. This realization fueled the demand for Purna Swaraj — complete independence, which soon became the central objective of the national movement.

Today, this message resonates strongly in modern India’s governance model, where decisions are made by elected representatives and not by external powers. The spirit of self-rule, born during this period, remains central to India’s national identity.

Conclusion: A Failed Commission, a Successful Legacy

Although the Simon Commission failed in its purpose, it succeeded in awakening India politically and morally. It united the nation, strengthened democratic values, and inspired the creation of India’s own constitutional vision. The movement surrounding the commission proves that even failed reforms can lead to transformative change when people stand together with courage and conviction.

The legacy of the Simon Commission reminds us that history’s most powerful lessons often come from moments of conflict — lessons that guide future generations toward justice, dignity, and democratic responsibility.

Conclusion

The Simon Commission of 1927 marked a crucial turning point in India’s struggle for freedom. Although introduced as a constitutional review mechanism by the British government, it quickly became a symbol of political exclusion and injustice in the eyes of the Indian people. The absence of Indian representation transformed the commission from an administrative body into a catalyst for nationwide unity, awakening, and resistance.

The protests that erupted across the country demonstrated the depth of India’s political maturity and collective consciousness. From the sacrifice of Lala Lajpat Rai to the fearlessness of students, workers, women, and ordinary citizens, the movement showed that when a nation stands together, its voice becomes impossible to silence. The Commission’s rejection also inspired Indian leaders to frame their own constitutional vision, leading to the creation of the Nehru Report and ultimately paving the way for the demand for Purna Swaraj — complete independence.

The legacy of the Simon Commission offers a powerful lesson: democracy thrives when people participate, protest, and demand accountability. Decisions imposed without representation never earn legitimacy. The movement surrounding the commission proved that the strength of a nation lies not merely in its institutions, but in the courage, unity, and aspirations of its people.

As we look at modern India, it becomes evident that the values strengthened during this period — representation, dignity, self-rule, and public participation — form the foundation of our democratic identity today. The story of the Simon Commission is not just a historical event; it is a reminder, an inspiration, and a guiding principle that the future of a nation must always be shaped by the voices of its own people.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What was the Simon Commission and why was it sent to India?

The Simon Commission, officially known as the Indian Statutory Commission, was sent by the British government in 1927 to review the working of the Government of India Act of 1919. Its purpose was to evaluate administrative reforms and recommend future changes. However, the commission became controversial because it included no Indian members, which led to widespread dissatisfaction.

2. Why were no Indians included in the Simon Commission?

The British government argued that only British members could conduct an “impartial” review. This reasoning was unacceptable to Indians, who saw it as a deliberate insult and a denial of their political maturity. The exclusion reinforced the belief that the British did not trust Indians to participate in decisions about their own governance.

3. Why was the Commission met with such intense protests?

The absence of Indian representation was the core reason behind the protests. Indians believed that reforms affecting their future must involve their participation. People across the country took to the streets with black flags, shouting “Simon Go Back!” as a symbol of their frustration and rejection of the commission. Political parties, students, workers, and ordinary citizens united in one of the largest protest movements of the time.

4. How did the death of Lala Lajpat Rai affect the movement?

During a peaceful demonstration against the Simon Commission in Lahore on 30 October 1928, the British police carried out a brutal lathi charge, severely injuring Lala Lajpat Rai. He passed away a few weeks later. His death deeply moved the nation, intensifying the protests and inspiring young revolutionaries such as Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru to take bold action.

5. What long-term impact did the Simon Commission protests have?

The protests strengthened India’s political awakening and pushed Indian leaders to develop their own constitutional framework. In 1928, The Nehru Report was drafted as India’s response, presenting a comprehensive proposal for self-governance. The movement also laid the foundation for the demand for Purna Swaraj (Complete Independence), declared in 1929.

6. What lessons does the Simon Commission offer to modern India?

The Simon Commission teaches that democracy thrives on representation, dialogue, and public participation. Any decision taken without involving the people is bound to fail. The episode also highlights the importance of unity, civic responsibility, and the right to protest. Modern India continues to draw inspiration from this historic movement to uphold democratic values and protect the dignity and voice of its citizens.

References

Below is a list of key historical sources, books, archival materials, and research documents that provide credible information on the Simon Commission (1927–1929) and the events surrounding it. You may add direct URLs to these sources if you want to make your article more detailed and academically enriched.

- 1. Bipan Chandra – “India’s Struggle for Independence”

A widely respected source covering the national movement and the protests against the Simon Commission. - 2. R.C. Majumdar – “History of the Freedom Movement in India”

Detailed coverage of political developments and nationalist responses during the 1920s. - 3. Stanley Wolpert – “A New History of India”

Analytical description of British policies, reform commissions, and the Indian reaction. - 4. The Nehru Report (1928)

India’s formal constitutional response to the Simon Commission, drafted under Motilal Nehru. - 5. National Archives of India

Original documents, government dispatches, and reports related to the Simon Commission (1927–1929). - 6. British Library – India Office Records

British government documents, commission files, and administrative papers from the period. - 7. Contemporary Newspapers (1927–1929)

Archival issues of The Hindu, Bombay Chronicle, The Pioneer, and other newspapers documenting protests and public reactions. - 8. “Modern India” – Sumit Sarkar

A modern historical analysis of nationalism, political resistance, and constitutional developments.