Introduction: My Journey to Understanding the Round Table Conferences (1930–32)

Some historical events do not remain confined to textbooks; they grow with us, challenge our understanding, and compel us to rethink how a nation’s destiny is shaped. The Round Table Conferences held between 1930 and 1932 are among such events. These conferences were not merely official meetings between British rulers and Indian leaders. They represented the intense struggle between colonial power and the rising voice of a nation yearning for freedom.

When I first read about the Round Table Conferences, they appeared to me as just “three meetings in London.” But as I explored deeper, I realized that these conferences were far more significant—and far more dramatic—than most people imagine. They brought together an extraordinary mix of personalities: Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Indian princes, British officials, and representatives of various communities, each carrying their own visions, fears, and expectations.

This introduction aims not simply to recount historical facts, but to take you back to that era—a time when India was undergoing intense political, social, and economic transformation. The British Empire was struggling with global economic turmoil and mounting international criticism, while the Indian freedom movement was gaining unprecedented momentum. India was divided in opinions but united in its determination for self-rule.

For me personally, the Round Table Conferences became a subject of fascination because they were not only about political negotiations; they were a live laboratory of dialogue, disagreement, compromise, and visionary leadership. These conferences taught me that freedom struggles are not only fought on the streets, in prisons, or through protests—they are also fought across the table, through ideas, through arguments, and through the courage to stand for what is just.

As you read through this article, you will notice that I am not merely presenting a chronological sequence of events. I am sharing the story of a nation discovering its voice, the story of leaders navigating unprecedented challenges, and the story of negotiations that shaped the political and constitutional future of India. Along with historical facts, I will also share my reflections, the lessons I learned, and the relevance these events hold for our modern democratic world.

Let us begin this journey—starting from the background that led to the first Round Table Conference, moving through the intense debates that defined the second, and finally witnessing the outcomes and long-term impact of all three. The story of the Round Table Conferences is not just history; it is a reminder that dialogue, diversity, and determination are the cornerstones of any nation’s progress.

Background: India in the 1920s — The Road to Negotiation

To understand the Round Table Conferences of 1930–32, we must first step into the turbulent decade of the 1920s. This was a period of political awakening, social unrest, and evolving leadership in India. The First World War had weakened imperial confidence, economic strains had intensified, and Indian public opinion was becoming increasingly assertive. The 1920s therefore framed a new reality: British administrators could no longer treat India as a passive colony indefinitely, and Indian leaders were moving beyond street protests toward demands for constitutional recognition and political participation.

The Non-Cooperation movement (1920–22) under Mahatma Gandhi marked the entry of mass politics into the freedom struggle. Millions joined in boycotts, swadeshi campaigns, and civil actions, demonstrating the potential power of united civic resistance. Although the movement was suspended after incidents such as the Chauri Chaura episode, its legacy was a transformed political landscape — more organized, broader in base, and impatient for meaningful political change.

In the late 1920s the British government attempted to address constitutional questions by commissioning the Simon Commission (1927). The Commission’s reception in India was hostile: it contained no Indian members and was seen as a symbolic denial of Indian political agency. The slogan “Simon Go Back” became a rallying cry across communities and regions, revealing both the unity and the underlying complexities of Indian public opinion. The Commission episode highlighted a central tension — Britain’s attempt to manage Indian reform from the outside, while Indian leaders demanded a seat at the table.

Parallel to mass movements were elite efforts at constitutional framing. The Nehru Report of 1928, penned by Indian leaders, proposed dominion status and a draft constitution. While progressive and an important assertion of Indian agency, the report failed to reconcile communal demands fully, especially those articulated by Muslim League leaders. The clash between majoritarian constitutional designs and communal safeguards would become a recurring theme in the discussions that followed.

Economically, India in the 1920s faced significant stress. Global economic fluctuations, agricultural distress, and unemployment intensified grievances among peasants, artisans, and urban workers. Local issues — land rights, taxation, and labour conditions — combined with national demands for political reforms to create a volatile, sometimes explosive, public mood. British administrators, conscious of unrest and global scrutiny, began to search for negotiated, constitutional solutions rather than mere coercion.

The spark that accelerated negotiations was the Salt Satyagraha of 1930. Gandhi’s Dandi march and the widespread civil disobedience campaigns that followed captured international attention and exposed Britain's moral and political vulnerability. The Salt movement demonstrated that political legitimacy could no longer be sustained solely through imperial authority; it required some form of political engagement with Indian aspirations.

Against this backdrop, British policymakers and Indian political leaders agreed that a formal forum for discussion might be necessary. The Round Table Conferences were conceived as an attempt to bring Indian representatives — political parties, princely states, communal groups, and civic organizations — face-to-face with British officials in London. The goal was to negotiate constitutional reforms that might defuse tensions, create a workable governance framework, and redefine India–Britain relations without immediate transfer of full sovereignty.

In short, the 1920s set the stage for negotiation: mass mobilization had shifted the balance of political power, elite constitutional debates revealed deep communal and regional divides, economic distress added urgency, and international opinion made peaceful settlement desirable. The three Round Table Conferences of 1930–32 were therefore not isolated events; they were the product of a decade in which India moved from agitation to argument — from street action to constitutional bargaining. Understanding this background is essential to appreciate why those conferences mattered, who took part, and what was at stake.

First Round Table Conference (1930): The Beginning of Dialogue

The First Round Table Conference began in London on 12 November 1930, at a moment when India was in the midst of intense political ferment. The Civil Disobedience Movement was spreading rapidly across the country, and British authorities were struggling to contain both domestic and international criticism. Yet, despite this pressure, the British government hoped that bringing together diverse Indian voices might create a foundation for constitutional reform.

However, the conference suffered a major limitation from the very outset — the Indian National Congress did not participate. As the leading political force in the freedom struggle, Congress represented a large section of the Indian population. Most of its top leaders were in jail, including Mahatma Gandhi, and the party boycotted the conference as a protest against repressive British policies. This absence created a visible void, making the discussions unbalanced and incomplete.

Despite this, the conference witnessed participation from 73 delegates representing a wide range of communities and interests: Muslim League leaders, Sikh representatives, the Depressed Classes (under Dr. B.R. Ambedkar), Anglo-Indians, Indian Christians, women’s organizations, business groups, and rulers of several princely states. Each group carried its own priorities — political safeguards, communal rights, economic concerns, and constitutional autonomy. Reconciling all these perspectives within a single framework proved to be a formidable challenge.

The British government placed on the table the idea of granting India “dominion status” at some point in the future. But without Congress participation, the proposal lacked the legitimacy needed to move forward. The discussions revolved around crucial questions: the balance of power between the Centre and provinces, the representation of minorities, the future of princely states, and the structure of a possible federal system.

Minority groups in particular emphasized fears of being dominated in a majoritarian system. The princely states, on the other hand, were reluctant to surrender their privileges in any new constitutional setup. Muslim leaders demanded separate electorates to safeguard political rights, while British officials looked for a formula that could satisfy all parties without weakening imperial interests.

Ultimately, the First Round Table Conference ended without any concrete agreement. It identified the problems but could not offer solutions. Yet, its significance should not be underestimated. It marked a historic moment when India’s diverse political voices were formally recognized and invited to shape the constitutional future of the country. More importantly, it set the stage for the Second Round Table Conference — where, for the first time, Mahatma Gandhi himself would arrive as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress.

Second Round Table Conference (1931): Gandhi’s Historic Participation and Pivotal Debates

The Second Round Table Conference, held in London from September to December 1931, stands as the most significant of the three conferences. For the first time, the Indian National Congress agreed to participate officially, and Mahatma Gandhi traveled to London as its sole representative. His presence transformed the atmosphere of the negotiations, turning the conference into a global event watched closely by politicians, journalists, and ordinary citizens across continents.

Gandhi’s arrival in London was unlike anything seen in British political circles. Dressed in his simple khadi shawl and loincloth, he appeared as a symbol of India’s moral resistance and cultural identity. His visit was not limited to formal halls; he walked through working-class neighborhoods, met with laborers, addressed students at universities, and interacted with groups across the social spectrum. To many in Britain, he became the human face of India’s struggle for freedom.

The primary purpose of the conference was to create a new constitutional framework for India. But as soon as discussions began, it became evident that reaching a consensus would be exceptionally difficult. Gandhi laid down a straightforward vision: a federal structure with strong provincial autonomy and a clear path toward dominion status. He argued firmly that India must be treated as a single nation, not as a collection of competing communities.

The most contentious issue, however, was the question of minority representation. Leaders of the Muslim League, Sikh community, Depressed Classes (represented by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar), Anglo-Indians, and Indian Christians demanded constitutional safeguards, separate electorates, or communal representation. Their fear was that, in a future democratic India, the majority community would dominate political decisions.

Gandhi opposed the idea of separate electorates, arguing that they would permanently divide the nation along social and religious lines. This brought him into direct conflict with Dr. Ambedkar, who insisted that the Depressed Classes needed separate electorates to protect themselves from centuries of discrimination. Their debate became the most intense and widely analyzed aspect of the conference — a clash between two visions of social justice and national unity.

The princely states also played a major role in the conference. Their rulers demanded guarantees that their autonomy and privileges would remain intact in any future constitutional system. Many princes were reluctant to join a federal structure unless they retained considerable internal authority. Congress, on the other hand, insisted that all states must be integrated into a democratic union with equal responsibilities.

The British government attempted to reconcile these competing interests, but the gaps proved too wide. Gandhi repeatedly emphasized that real progress was impossible without a firm British commitment to self-rule. Yet the British side hesitated to grant sweeping concessions, preferring to delay key decisions until broader consensus emerged among Indian leaders.

In the end, the Second Round Table Conference concluded without a final agreement. But the significance of the conference cannot be measured solely by its outcome. It exposed the deep social, political, and communal divisions within India, revealed the limitations of British constitutional policy, and demonstrated the moral authority Gandhi carried as the voice of India’s national movement.

Although it failed to deliver immediate results, the conference played a decisive role in shaping future negotiations, influencing the Poona Pact, and laying the groundwork for the Government of India Act of 1935. It remains a reminder that India’s freedom struggle unfolded not only on the streets but also in the halls where difficult, often painful, conversations took place.

Third Round Table Conference (1932): The Final Stage of Negotiation

The Third Round Table Conference, held in London in November and December 1932, marked the final attempt by the British government to shape a constitutional framework for India through dialogue. However, unlike the previous two conferences, this one took place in an atmosphere of disappointment, exhaustion, and deepening political divides. Most significantly, the Indian National Congress once again did not participate.

After returning from the Second Conference, Mahatma Gandhi was arrested, and the Civil Disobedience Movement faced severe repression across India. These developments widened the mistrust between Congress and the British government. Without Congress — the principal representative of Indian national opinion — the conference lacked legitimacy and appeared incomplete from the very beginning.

The delegates who did attend represented princely states, the Muslim League, the Depressed Classes, the Sikh community, Anglo-Indians, Indian Christians, and several other groups. Although many of them presented their demands with seriousness, the absence of a unifying national voice meant the discussions remained fragmented. Each group focused on protecting its own interests rather than shaping a coherent national agreement.

The conference mainly revolved around two core issues:

1. The final structure of the proposed All-India Federation

2. Safeguards and representation for minority communities

The British government pushed for a federal model that would combine British Indian provinces and princely states into

a single political framework. However, the princes were reluctant to surrender their internal autonomy and resisted

any arrangement that placed them under a central democratic authority.

Minority groups reiterated their demands for constitutional safeguards. The Muslim League emphasized its desire for effective representation at the Centre, while other communities expressed concerns about maintaining political influence in a future democratic India. Without Congress in the room, these discussions had no balancing force, and no consensus could emerge.

Ultimately, the Third Round Table Conference concluded without significant progress. Unable to secure agreement among the delegates, the British government decided to move forward independently. The outcome of their unilateral decision was the Government of India Act, 1935, which drew heavily from the discussions held across all three conferences but did not reflect true Indian consensus.

In retrospect, the Third Conference highlighted an important truth: meaningful constitutional negotiation requires the participation of all major stakeholders. Without national leadership at the table, dialogue becomes symbolic rather than productive. Although the conference failed to produce a shared constitutional plan, it revealed the complex realities of India’s political landscape and underscored the necessity of united leadership in the struggle for freedom.

Key Personalities: Leaders Who Shaped the Round Table Conferences

The Round Table Conferences (1930–32) brought together a unique collection of political thinkers, social reformers, community representatives, and imperial administrators. Their contrasting visions, disagreements, and negotiations shaped not only the outcome of the conferences but also the future trajectory of India’s constitutional development. This section explores the major personalities whose presence and ideas defined these historic meetings.

Mahatma Gandhi: The Moral Voice of the Indian Nation

Mahatma Gandhi participated only in the Second Round Table Conference, yet his impact was profound. As the sole representative of the Indian National Congress, he carried the weight of millions of Indians who saw Congress as the national vehicle for freedom. Gandhi’s simplicity, his unyielding belief in nonviolence, and his insistence on the unity of India challenged both the British leadership and competing Indian groups.

Gandhi argued that India was a single nation, not a loose collection of religious communities. He opposed separate electorates, believing they would deepen divisions and weaken the foundations of national unity. His presence transformed the conference into a moral battleground, where the principles of equality, justice, and self-rule were debated with urgency.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: Champion of the Depressed Classes

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar emerged as one of the most powerful and articulate voices in all three conferences. Representing the Depressed Classes (today known as Scheduled Castes), he demanded constitutional safeguards to protect those who had suffered centuries of discrimination and exclusion. Ambedkar believed that political empowerment was essential to ensuring social justice.

His demand for separate electorates for the Depressed Classes led to dramatic debates with Gandhi. While Gandhi sought a unified Indian identity, Ambedkar insisted that unity without justice would merely preserve inequality. Their intellectual confrontation became a defining moment in India's freedom struggle, eventually influencing the historic Poona Pact.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah: Architect of Muslim Political Demands

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a leading figure of the Muslim League, played a central role in articulating the political aspirations of the Muslim community. Jinnah argued that Muslims were a nation with distinct political identity and therefore required constitutional safeguards, including separate electorates and adequate representation at the Centre.

His firm stance reflected growing concerns within the Muslim community about being overshadowed in a majoritarian democracy. Jinnah’s positions during the conferences foreshadowed later developments that would ultimately shape the subcontinent’s political destiny.

Princes and Rulers of Indian States: Guardians of Autonomy

The princely states were represented by their rulers, who were determined to preserve their internal autonomy and privileges. They were cautious about joining any federation that placed them under the authority of a central democratic government. Their participation was essential for the British plan of an All-India Federation, yet their reluctance became one of the obstacles in creating a unified constitutional structure.

British Leadership: Balancing Empire and Reform

British policymakers such as Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, Secretary of State for India Samuel Hoare, and Lord Irwin played equally important roles. They attempted to craft a constitutional solution that would satisfy Indian demands while protecting imperial interests. However, their proposals often fell short of Indian expectations and failed to fully recognize the urgency of the freedom movement.

The British leadership promoted a federal structure and communal safeguards but struggled to reconcile the conflicting demands of Indian groups. Their cautious, incremental approach contrasted sharply with the rising impatience of Indian leaders seeking meaningful self-rule.

A Collective Legacy

Together, these leaders turned the Round Table Conferences into a stage of intense debate and ideological conflict. Gandhi represented moral authority, Ambedkar championed social justice, Jinnah articulated minority rights, the princes defended autonomy, and the British guarded empire. Their interactions revealed the diversity and complexity of India's political landscape, highlighting that the struggle for freedom was also a struggle to define national identity, equality, and the future of democracy.

Major Debates: Clashing Visions and the Search for Constitutional Balance

The Round Table Conferences (1930–32) were not simply meetings between Indian leaders and British officials. They were arenas of political contest, ideological conflict, and competing visions about the future of India. The debates that unfolded across these conferences revealed the deep complexities of Indian society and showcased the competing priorities that made consensus extremely difficult. These discussions later influenced the drafting of the Government of India Act, 1935, and ultimately shaped India’s constitutional journey.

1. Separate Electorates: The Most Contentious Issue

The most heated and divisive debate revolved around the demand for separate electorates. Minority communities — including Muslims, Sikhs, Anglo-Indians, Indian Christians, and the Depressed Classes represented by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar — sought separate political representation to safeguard their identity and rights. Their argument was grounded in historical experience: in a democratic system dominated by the Hindu majority, minorities feared losing influence over political decisions.

On the opposite side stood the Indian National Congress, represented by Mahatma Gandhi in the Second Conference. Gandhi argued strongly against separate electorates, warning that they would fracture India permanently along religious and caste lines. According to him, political separation would prevent the emergence of a unified Indian nationhood. This clash between Gandhi’s vision of national unity and minority leaders’ demand for security became the central debate of the conferences.

The Gandhi–Ambedkar Conflict

The disagreement between Gandhi and Dr. Ambedkar became the most intense ideological confrontation of the conferences. Ambedkar insisted that separate electorates were essential for the political empowerment of the Depressed Classes, arguing that without them, equality would remain an illusion. Gandhi countered that such provisions would permanently divide Hindu society and institutionalize caste segregation. This clash eventually paved the way for the later Poona Pact, but during the conferences it remained unresolved and deeply divisive.

2. Federal Structure: Integrating Provinces and Princely States

Another major debate centered on the proposed All-India Federation — a constitutional model that would unify British Indian provinces and princely states under a single federal structure. The British pushed this plan to stabilize governance, but the idea faced resistance from multiple sides.

The princely states were reluctant to surrender any meaningful authority to a central democratic government. They wanted to join the federation on their own terms, preserving their internal autonomy and special privileges. Meanwhile, Congress insisted on a federal structure with democratic accountability, something the princes were unwilling to accept.

The Dilemma of the Princes

The rulers of princely states feared that joining a powerful federal center would diminish their control. Their hesitation created a major obstacle in finalizing the federal plan. It raised critical questions: Could a federation work without their full cooperation? And could princely states be integrated without compromising democratic principles?

3. Division of Powers Between Centre and Provinces

Another vital issue was the distribution of powers in the proposed constitution. Congress demanded greater provincial autonomy, arguing that local governments needed authority over education, agriculture, law and order, and economic development. British officials, however, wanted centralized control over defense, finance, and foreign affairs.

This debate highlighted the core tension between Indian aspirations for self-governance and British concerns about maintaining political and strategic control. The question underpinning this debate was crucial: Would India become a truly self-governing dominion, or remain under imperial oversight?

4. Dominion Status vs. Complete Independence

Congress demanded a clear path to dominion status — and eventually full independence. Gandhi emphasized that India must have the freedom to shape its own destiny. Britain, however, hesitated to grant such sweeping authority, citing India's internal disagreements as justification for delay.

This debate exposed the fundamental gulf between the two sides: Congress sought genuine self-rule, while Britain aimed to preserve imperial influence as long as possible.

5. Social Justice and Internal Inequalities

Beyond constitutional and political issues, several delegates raised concerns about social inequalities within India. Dr. Ambedkar, women’s representatives, and minority leaders emphasized the need for safeguards in education, employment, and public representation to ensure that independence would lead not only to political freedom but also to social justice.

Conclusion

The debates of the Round Table Conferences revealed a politically diverse and socially complex nation struggling to define its future. Although the conferences did not produce definitive solutions, they exposed the core challenges of building a unified yet diverse India. These debates laid the intellectual foundation for future negotiations, influenced the Government of India Act of 1935, and shaped the constitutional principles that would guide India after independence.

Outcomes: Achievements, Limitations, and Lasting Impact of the Round Table Conferences

The Round Table Conferences (1930–32) marked a turning point in India's constitutional history. Although these conferences did not produce a definitive political settlement, they significantly shaped the structure of future reforms and revealed the complexities of India's social and political landscape. Their outcomes were a combination of partial progress, unresolved disagreements, and important lessons for India’s freedom struggle.

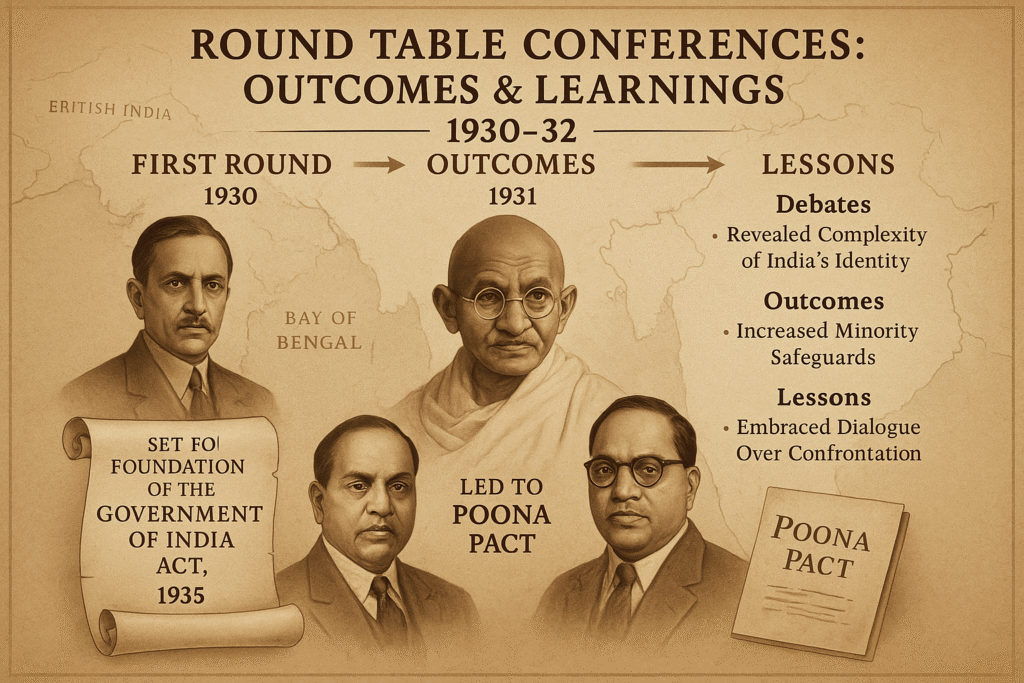

1. Foundation of the Government of India Act, 1935

The most direct and tangible outcome of the Round Table Conferences was the formulation of the Government of India Act, 1935. While the Act was drafted by the British government without full Indian agreement, it was heavily influenced by the discussions, proposals, and debates that took place during the three conferences.

The Act introduced provincial autonomy, expanded legislative representation, proposed a federation of British Indian provinces and princely states, and made changes to the electoral system. Although many Indian leaders found the Act inadequate, it laid the administrative foundations that would later shape independent India’s democratic structure.

2. Emergence of the Minority Question as a Central Issue

One of the strongest outcomes of the conferences was the clear articulation of minority concerns. Muslims, Sikhs, the Depressed Classes (led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar), Anglo-Indians, and Indian Christians all expressed the need for constitutional safeguards.

The debates proved that India was not a homogenous society but a deeply diverse nation where political representation had to account for multiple identities. This realization became crucial for future constitutional planning and influenced discussions on representation, reservations, and communal electorates.

3. Gandhi–Ambedkar Conflict and the Path to the Poona Pact

The intense disagreement between Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Ambedkar over separate electorates was one of the most significant developments emerging from the conferences. Although the conferences themselves did not resolve the matter, the debate set the stage for the landmark Poona Pact of 1932.

The Poona Pact replaced separate electorates with reserved seats for the Depressed Classes, fundamentally shaping India's approach to social justice and political representation. This was one of the most lasting legacies of the ideological confrontation at the Round Table Conferences.

4. Growing Mistrust Between the British Government and Congress

The conferences also widened the gap between the British government and the Indian National Congress. The arrest of Gandhi after the Second Conference and the suppression of the Civil Disobedience Movement increased mistrust and convinced many Indian leaders that the British were unwilling to offer meaningful self-rule.

This realization strengthened the resolve of Indian nationalists that independence would not come through negotiations alone, but through sustained mass movements and political pressure.

5. Clarification of the Federal Vision for India

Although the proposed All-India Federation did not materialize during the conferences, the debates clarified the direction India's political framework would take. The conferences made it clear that India would eventually have a federal structure combining provinces and princely states.

This concept later became a cornerstone of India’s post-independence constitutional design.

6. India's Political Voice Gains International Recognition

Gandhi’s participation in the Second Round Table Conference, along with global media attention, helped present the Indian freedom struggle on an international stage. India was increasingly seen as a nation demanding justice, self-determination, and equality.

Conclusion

The outcomes of the Round Table Conferences were mixed. They did not produce an immediate constitutional settlement, but they played a crucial role in shaping India’s political future. They highlighted India's internal complexities, clarified the challenges of building a democratic nation, and laid the groundwork for future reforms. Importantly, they helped India recognize that the road to freedom required both negotiation and mass struggle — a synthesis that ultimately guided the nation to independence.

Learnings: Lessons from the Round Table Conferences

The Round Table Conferences of 1930–32 were not merely political events; they were classrooms of dialogue, reflection, and negotiation. Even though they did not produce a final constitutional settlement, the conferences taught India invaluable lessons about leadership, democracy, social justice, and the challenges of building a unified nation. These lessons continue to guide India’s political and social journey even today.

1. Dialogue is the foundation of resolution

One of the most important lessons from the conferences is that meaningful solutions emerge through conversation, not confrontation. The conferences showed that even when agreements seem impossible, bringing diverse voices to the table is essential for national progress. This principle remains central to modern democratic decision-making.

2. Diversity must be embraced, not feared

The debates highlighted India’s vast diversity — religious, social, cultural, and political. The inability to achieve full consensus during the conferences demonstrated how complex India's identity is. Yet it also reinforced a key lesson: a truly successful nation must respect, recognize, and integrate its multiple identities rather than suppress them.

3. Social justice is essential for real freedom

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s strong advocacy for the rights of the Depressed Classes emphasized that political independence alone is not enough. A nation cannot be truly free unless every community — especially those historically oppressed — receives dignity, representation, and opportunity. This principle became a cornerstone of India’s Constitution and remains a guiding value today.

4. Leadership requires moral courage and vision

The contrasting roles of Gandhi, Ambedkar, Jinnah, and other leaders offered profound lessons in leadership. These conferences proved that effective leadership is not only about power or position, but about moral strength, clarity of purpose, and the ability to listen and negotiate. Their debates continue to inspire discussions on leadership in modern governance.

5. National unity is essential for long-term progress

The conferences revealed that deep internal divisions can weaken a nation’s political struggle. Without unity, negotiations become fragmented and less effective. This learning shaped later movements that stressed collective action and common purpose, eventually guiding India toward independence.

Overall, the Round Table Conferences remind us that freedom is not a single event but an evolving process — one that requires continuous dialogue, fairness, courage, and commitment to building an inclusive society. These lessons remain as relevant today as they were in the early 20th century.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of the Round Table Conferences

The Round Table Conferences of 1930–32 stand as one of the most critical turning points in India’s constitutional and political history. Although they did not deliver an immediate or complete settlement, these conferences reshaped the way India understood negotiation, diversity, representation, and the long journey toward self-governance. Their legacy continues to influence India’s democratic framework and constitutional values even today.

The dialogues and debates highlighted the essential truth that nation-building is not achieved through force or unilateral decisions, but through conversation, compromise, and mutual respect. Leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and the rulers of princely states demonstrated that leadership requires not only political strength but also ethical conviction, intellectual clarity, and the willingness to listen to opposing viewpoints.

One of the most powerful lessons from the conferences was that political freedom is incomplete without social justice. The deep discussions around minority rights, representation, and the upliftment of oppressed communities revealed that true independence must ensure equality, dignity, and fair participation for all sections of society. These ideas later shaped essential pillars of the Indian Constitution — reservations, fundamental rights, and protections for socially disadvantaged groups.

The conferences also underlined that India's strength lies in its diversity. The inability to reach a unified agreement demonstrated how complex and layered India’s social fabric is. However, the very act of bringing representatives from different religions, castes, regions, and political ideologies to one table set an important precedent — that democracy thrives when diverse voices are heard, acknowledged, and integrated into decision-making processes.

In the modern era, the principles reflected in these conferences remain highly relevant. Whether in governance, public policy, or social harmony, inclusive dialogue and respect for pluralism are crucial for sustaining a stable and just society. The Round Table Conferences therefore serve as a reminder that democracies do not succeed through uniformity, but through cooperation and coexistence.

Ultimately, the Round Table Conferences teach us that history is not just a record of past events — it is a guidebook for the present and a blueprint for the future. They remind us that the road to freedom, justice, and unity is built on continuous effort, honest dialogue, and unwavering commitment to equality. As we move forward, these lessons remain essential to shaping a stronger, more inclusive, and more democratic India.

Questions and Answers

1. What were the Round Table Conferences?

The Round Table Conferences were three important political meetings held in London between 1930 and 1932 to discuss India's constitutional future with British officials and Indian representatives.

2. Why were the conferences held?

They were held to find a constitutional solution for India, resolve political tensions, and address issues like federal structure and minority representation.

3. How many conferences took place?

Three conferences were held: (1) First – 1930 (2) Second – 1931 (3) Third – 1932

4. Who represented the Indian National Congress?

Mahatma Gandhi represented the Indian National Congress at the Second Round Table Conference as the only official delegate.

5. Why did Congress boycott two conferences?

Congress boycotted the First and Third Conferences due to imprisonment of leaders and lack of trust in British intentions.

6. What role did Dr. B.R. Ambedkar play?

Dr. Ambedkar represented the Depressed Classes and strongly advocated for separate electorates and political safeguards for marginalized communities.

7. What were the major issues discussed?

Major issues included federal structure, minority rights, separate electorates, princely states' role, and the question of self-rule.

8. What was the Gandhi–Ambedkar disagreement?

Gandhi opposed separate electorates for the Depressed Classes, while Ambedkar supported them for ensuring political empowerment.

9. What was the outcome of the conferences?

Although no final agreement was reached, the discussions laid the foundation for the Government of India Act, 1935.

10. Why did the conferences fail?

They failed due to disagreements among Indian groups, lack of Congress participation in two sessions, and British unwillingness to offer full self-rule.

11. How did the princely states respond?

Princely states wanted to preserve their autonomy and were hesitant to join a central federation unless their privileges were protected.

12. How did the conferences influence India’s independence movement?

They exposed the limits of British concessions and strengthened the Indian resolve for complete independence.

References

- Primary Sources on the Indian Freedom Movement

"Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi" – Publications Division, Government of India.

Includes letters, speeches, and writings relevant to the Round Table Conferences. - Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s Writings

"Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches" – Edited by Vasant Moon.

Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. - Proceedings of the Round Table Conferences (1930–32)

British National Archives – Official transcripts and government documents from all three conferences. - Government of India Act, 1935

Official text of the Act as published by the British Parliament and Indian legislative records. - Books on Modern Indian History

Bipin Chandra – "Modern India"

Sumit Sarkar – "Modern India: 1885–1947"

R.C. Majumdar – "History of the Freedom Movement in India" - Academic Journals and Research Papers

JSTOR, Oxford University Press, and Cambridge University Press publications

Covering topics such as constitutional reforms, Indian nationalism, and minority politics. - Newspaper Archives (Historical)

The Times (London), The Hindu, and The Indian Express

Featuring reports and editorials from the period of the Round Table Conferences. - Studies on Indian Constitution and Political Development

D.D. Basu – "Introduction to the Constitution of India"

Granville Austin – "The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation" - Biographies of Key Personalities

Louis Fischer – "The Life of Mahatma Gandhi"

Dhananjay Keer – "Dr. Ambedkar: Life and Mission"