Introduction: India’s Physical Fabric and Why It Matters

India’s physical geography is more than a background on which history unfolds — it is an active participant in the story of the nation. From the snow-clad summits of the Himalayas to the broad ribbon of the Gangetic plains, from the ancient Deccan plateau to the long, indented coastline, the country’s landforms shape climate, livelihoods, culture, and policy. Understanding these physical regions helps explain why certain crops flourish in one place and fail in another, why monsoon patterns can make or break harvests, and why coastal towns face different risks and opportunities compared to upland communities. In short, geography is the silent architect of daily life.

I have often found that personal experience makes these abstract facts tangible. Walking through a foothill village after the first rains, hearing the farmers celebrate, or watching a river swell after distant snowmelt — these moments reveal how intimately people are tied to land and water. The Himalayas do not merely stand as a scenic barrier; they control monsoon trajectories, feed major rivers, and form unique ecosystems that communities depend upon. Likewise, the Gangetic plains are not just fertile soil; they are living corridors of agriculture, settlement, and history that have supported dense human populations for millennia.

Yet the same physical features that provide opportunity also present vulnerability. Erratic monsoon onset, glacier retreat, riverbank erosion, and coastal inundation are emerging realities under a changing climate. These challenges force us to think of geography not only as a way to classify landforms but as a set of constraints and possibilities that policy makers, planners, and citizens must engage with. Infrastructure, water management, conservation, and local knowledge systems all intersect with physical geography in shaping resilient futures.

This introduction sets the stage for a deeper exploration of India’s physical regions — examining mountains, plains, plateaus, coasts, rivers, and climatic patterns — while weaving in stories and practical insights. The aim is to make the subject accessible and relevant: to show how place influences culture, economy, risk, and hope. Whether you are a student seeking context, a planner thinking about sustainable development, or a curious reader interested in how landscapes shape human choices, the following sections will offer both factual clarity and lived perspective. Let us begin this journey across India’s diverse and dynamic physical terrain.

India's Major Physical Regions

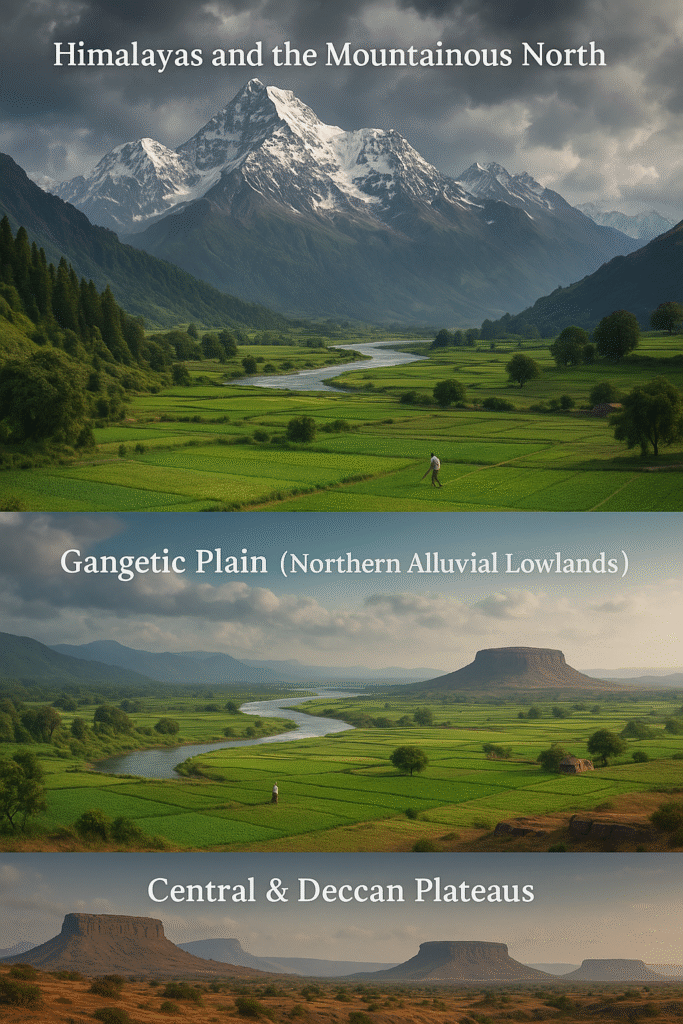

Himalayas and the Mountainous North

Location and Structure

The Himalayas form India’s northern backbone — a young, tectonically active mountain range that stretches from the northwest near Pakistan across to the northeast bordering Bhutan and Myanmar. Geologically the range is typically divided into the Outer Himalaya (Shivaliks), the Lesser or Middle Himalaya, and the Greater or High Himalaya with its towering snowbound peaks and extensive glaciers. This stratified structure creates sharp altitude gradients over short horizontal distances, producing a mosaic of microclimates and habitats.

Hydrological and Ecological Role

Functionally, the Himalayas are India’s great water tower: glaciers, snowfields and orographic rainfall feed perennial rivers that flow down into the plains. Rivers that originate here sustain agriculture, generate hydropower, and support dense populations downstream. Ecologically, the mountain slopes hold temperate forests, alpine meadows, and unique biodiversity hotspots with many endemic species. The mountains also create climatic barriers: they intercept monsoon winds and strongly influence rainfall distribution across the subcontinent.

Human Dimension and Risks

Human communities in the Himalayan region have adapted to steep slopes and seasonal extremes — terrace farming, pastoral routes, and trade pathways reflect centuries of place-based knowledge. At the same time, the Himalayas are highly vulnerable: seismic activity, slope failure, glacial retreat, and flash floods are recurring risks. Sustainable development here requires combining traditional ecological knowledge with modern engineering and a cautious approach to infrastructure, since poorly sited roads or unregulated construction can amplify hazard exposure.

Gangetic Plain (Northern Alluvial Lowlands)

Extent and Soils

The Gangetic Plain is India’s most extensive alluvial lowland, formed by sediments deposited over millennia by the Ganges and its tributaries. Stretching east-west across northern India, the plain features deep, fertile soils that have supported intense agriculture since antiquity. The topography is broadly flat, punctuated by river channels, oxbow lakes, and seasonal floodplains that renew soil fertility each year.

Agriculture, Economy and Society

This plain is often called India’s granary: wheat, rice, sugarcane, and pulses are major crops, produced through a combination of rainfed and irrigated farming. High population densities in the region have given rise to prosperous market towns, large agrarian economies, and complex social landscapes tied to land and water. Cultural life — festivals, pilgrimage circuits, and urban growth — is deeply entwined with rivers, which act as both resources and symbols.

Advantages and Challenges

The productivity of the Gangetic Plain is also its vulnerability. Seasonal floods are a recurrent hazard that can both enrich and devastate farmland. Groundwater depletion, river pollution from industrial and domestic sources, and unsustainable agricultural intensification are contemporary problems. Integrated river basin management, improved drainage, and sustainable irrigation practices are crucial to maintain the plain’s productivity while protecting ecosystems and livelihoods.

📦 Product Title Here

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Rating Here

🔹 Feature or benefit #1

🔹 Feature or benefit #2

Central and Deccan Plateaus

Geology and Landforms

The central Indian and Deccan plateaus are ancient, eroded tablelands characterized by hard basaltic and metamorphic rocks. These plateaus sit elevated above the surrounding plains and are often dissected by valleys and escarpments. The Deccan Traps, a vast basaltic plateau in peninsular India, testify to ancient volcanic activity and create a distinctive landscape of flat-topped hills and black cotton soils in parts.

Resources and Livelihoods

These plateaus are rich in mineral resources — coal, iron ore, bauxite and other deposits have driven industrial development and mining. Agricultural systems vary: rain-fed crops such as millets and pulses are common in drier zones, while irrigated pockets support more intensive cropping. The socio-economic fabric often reflects a mix of rural farming communities and mining towns, with resource extraction shaping local economies and regional connectivity.

Development Constraints

Plateau regions face water scarcity in many areas, soil degradation, and the environmental impacts of large-scale mining. Enhancing watershed management, supporting drought-resilient crops, and ensuring responsible mining practices are essential steps toward balanced and sustainable development of these upland landscapes.

Southern Plateaus and Coastal Plains

Physical Characteristics

South of the central plateaus, the peninsular region meets long coastal plains on both the eastern and western margins. The eastern coast features the Coromandel plains and wide river deltas, while the western coast is narrower with a series of lagoons, backwaters, and estuaries. Coastal geomorphology here includes beaches, mangrove belts, and in some areas, rocky headlands and cliffs.

Economic and Ecological Importance

These coastal belts support fisheries, ports, salt pans, agriculture on fertile deltas, and thriving urban clusters. Mangroves and coastal wetlands provide nursery grounds for fish, protect shorelines, and store carbon. In many regions, tourism and marine transport are significant economic drivers, linking local economies to national and global markets.

Vulnerabilities and Management Needs

Coastal zones are on the frontlines of sea-level rise, storm surges, and coastal erosion. Urbanisation along the shore often reduces natural buffers like dunes and mangroves. Effective coastal zone management — preserving natural buffers, regulating construction, and planning for rising seas — is central to sustaining livelihoods and biodiversity along these shores.

Island and Maritime Regions (Andaman & Nicobar, Lakshadweep)

Unique Features

India’s island groups — notably the Andaman & Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Lakshadweep archipelago in the Arabian Sea — host unique marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Coral reefs, seagrass beds, and tropical forests support high biodiversity and endemic species. These islands are also strategic maritime locations with small, closely-knit human communities that depend on fishing, coconuts, and low-impact tourism.

Conservation and Resilience

Islands are especially vulnerable to coastal inundation, coral bleaching, and extreme weather. Conservation efforts that prioritize reef protection, sustainable fishing, community-based tourism, and disaster preparedness strengthen both ecological integrity and human well-being. Given their limited land area and resources, island resilience planning must balance development needs with strict environmental stewardship.

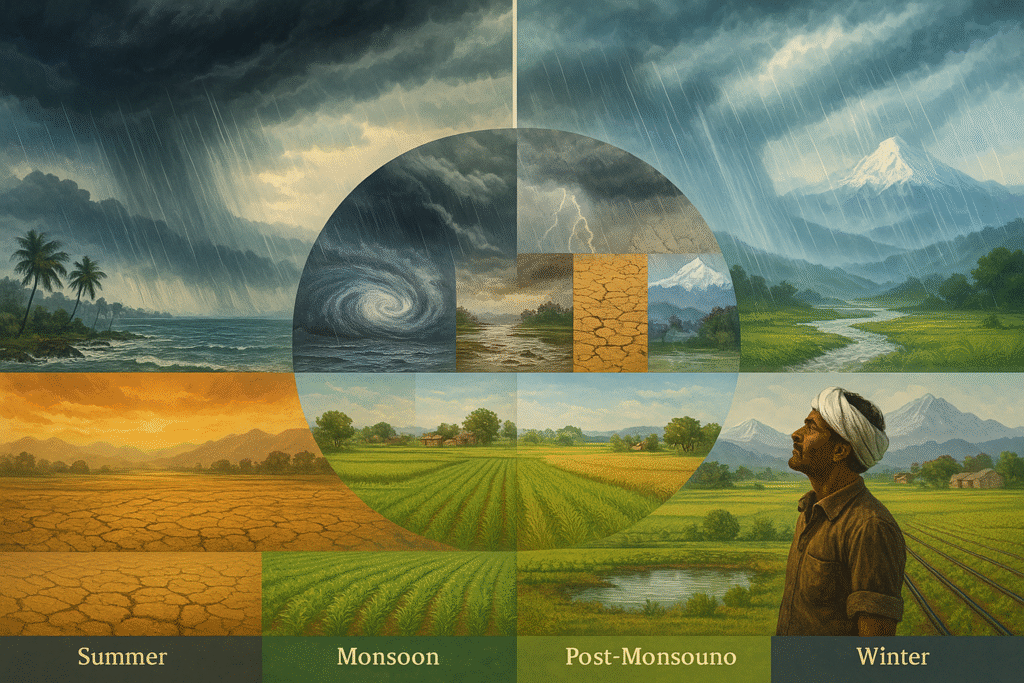

Climate and Seasonal Influences: From Monsoon Rhythms to Extreme Events

India’s climate is as diverse as its landscapes — a country where tropical coastlines, arid deserts, cool highlands, and humid plains coexist within a single subcontinent. At the heart of this diversity lies the monsoon system, the most defining feature of India’s climate. The southwest monsoon (June–September) brings nearly 70% of the country’s annual rainfall, while the northeast monsoon (October–November) significantly influences the southeastern coastal regions. These seasonal winds determine agricultural cycles, water availability, river discharge, and even cultural calendars. Growing up in a rural setting taught me how deeply communities depend on the precise timing of monsoon rains—farmers would prepare their fields weeks in advance, waiting for the first clouds to gather over the horizon.

India experiences four broad seasons: the scorching summer (March–May), the monsoon rains (June–September), a retreating/post-monsoon phase (October–November), and the winter season (December–February). Each region responds differently to these shifts. Coastal areas experience moderate temperatures and high humidity; the northern plains face extreme heat followed by dramatic relief from monsoon storms; and the Himalayan region witnesses cold, snowy winters with short, cool summers. These variations shape everything from the crops that thrive in each region to the design of houses and local water management traditions.

In recent decades, climate variability has increased, bringing more frequent and extreme weather events. Monsoon onset has become less predictable, rainfall distribution more erratic, and drought-flood cycles more severe. For example, delayed rain can dry up sowing fields, leading to crop losses, while sudden cloudbursts or glacial lake outburst floods can devastate mountain communities. Rising global temperatures are accelerating glacier melt in the Himalayas, temporarily increasing river flow but reducing long-term water security. Coastal regions face rising sea levels, more intense cyclones, and saline intrusion into agricultural land.

To address these challenges, India is adopting a range of adaptation strategies. Climate-smart agriculture — including drought-resistant seeds, micro-irrigation, crop diversification, and improved soil practices — is helping farmers cope with unpredictable rainfall. Water conservation structures, such as check-dams, rainwater harvesting systems, and groundwater recharge pits, offer resilience during dry spells. Traditional ecological knowledge, refined over generations, remains invaluable: indigenous water storage methods, crop rotations, and local weather observations often complement scientific forecasting effectively.

Accurate weather forecasting is another critical tool. The India Meteorological Department (IMD), supported by satellite systems and improved climate models, now provides more timely predictions and early warnings for extreme events. These forecasts help farmers decide when to sow crops, guide disaster management teams to prepare for floods or cyclones, and assist policymakers in planning seasonal water allocation. Early warning systems, strengthened embankments, and modern flood-control structures play an important role in reducing the impact of disasters.

Urban areas, too, are facing new challenges: heatwaves, intense short-duration rainfall leading to flash floods, and pollution-induced temperature fluctuations. Cities must embrace green infrastructure—urban forests, rooftop gardens, permeable pavements, and sustainable drainage systems—to regulate temperatures and manage excess water. Energy systems must adapt as well, with renewable sources offering stability during climate-induced disruptions.

Ultimately, climate and seasonal influences are not merely environmental phenomena — they are deeply social and economic realities. They determine food security, public health, migration, and the rhythm of daily life. Responding to these challenges demands a combination of strong policies, community participation, scientific innovation, and environmental awareness. As India continues to develop, understanding the dynamic interplay between climate and geography becomes essential to building resilient and sustainable futures for all.

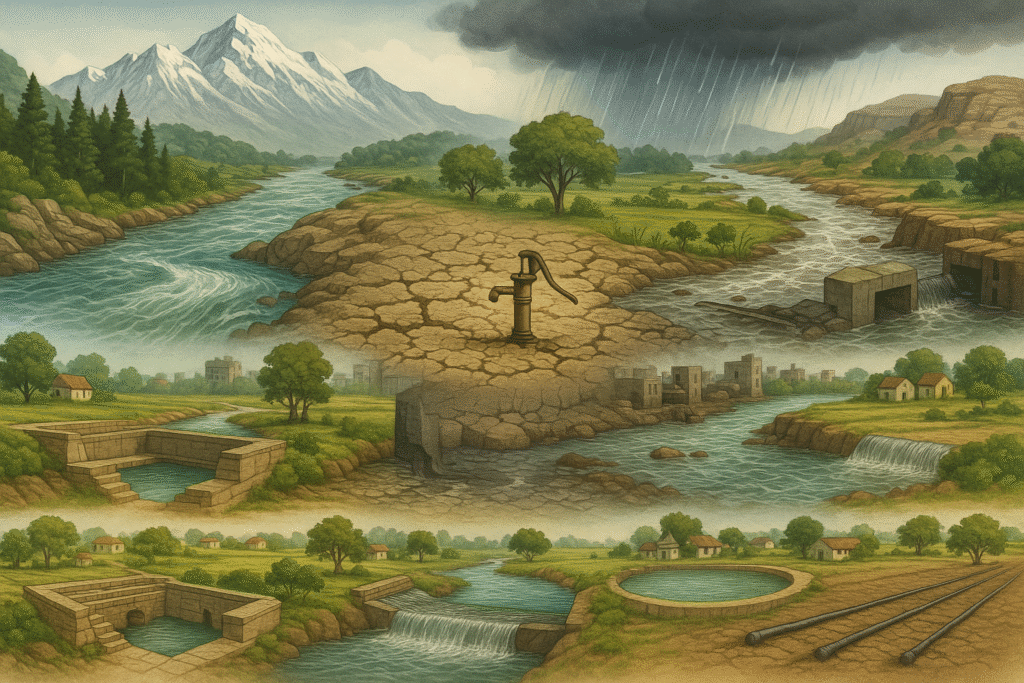

Water Resources and Rivers: The Lifelines of India

Water has always been central to India’s civilization, economy, and cultural identity. From ancient settlements along riverbanks to modern agricultural and industrial systems, rivers have shaped the subcontinent’s growth in countless ways. India’s rivers originate from two major sources: the snow-fed Himalayan system and the rain-fed Peninsular system. The Himalayan rivers — such as the Ganges, Yamuna, and Brahmaputra — are perennial, receiving water from melting glaciers and seasonal rainfall, which ensures continuous flow throughout the year. In contrast, Peninsular rivers like the Godavari, Krishna, Cauvery, Narmada, and Tapi rely mainly on monsoon rainfall and therefore show greater seasonal variation.

The Himalayan rivers play a crucial role in agriculture, drinking water supply, transportation, and hydropower generation. The Ganga-Brahmaputra basin, one of the most fertile and densely populated regions in the world, owes its agricultural richness to the alluvial soil deposited by centuries of river flooding. Peninsular rivers, flowing across the Deccan Plateau, often have rocky beds and steeper gradients, which contribute to the creation of reservoirs and dams essential for irrigation and power. The Narmada and Tapi rivers, which flow westward into the Arabian Sea, are unique examples of rivers shaped by the geological structure of the plateau.

However, managing India’s water resources is becoming increasingly complex. Irregular monsoons, over-extraction of groundwater, and rising temperatures have intensified water scarcity in several regions. Floods and droughts frequently occur within the same year, affecting different states simultaneously. Urbanization adds another layer of challenge: encroached riverbanks, polluted drains, untreated sewage, and industrial waste discharge have severely degraded major rivers like the Ganges and Yamuna. Coastal areas face additional threats such as saltwater intrusion due to rising sea levels and excessive groundwater extraction.

To address these challenges, India is adopting a combination of traditional and modern water management strategies. Traditional systems — including village ponds, stepwells, and community tanks — continue to play a significant role in groundwater recharge. Modern interventions such as check-dams, rainwater harvesting structures, micro-irrigation systems, and large-scale river rejuvenation programs are strengthening water security. Government-led initiatives for river cleaning, watershed management, and inter-state water-sharing frameworks aim to create long-term resilience.

Sustainable water management also requires community participation. Farmer-led water user groups, citizen-driven river cleanup movements, and local water budgeting practices are encouraging signs of cooperative action. At a broader level, integrating scientific research with local knowledge, improving data-based decision-making, and promoting eco-friendly policies are essential steps for future water security. India’s rivers are not just hydrological entities; they are cultural anchors, economic engines, and ecological corridors. Protecting them is fundamental to safeguarding the nation’s future.

Natural Resources and Their Impact on the Economy

India’s natural resources—minerals, forests, water, fertile soils, marine ecosystems, and diverse energy sources—form the foundation of its economic structure. The country’s vast geographical diversity has created pockets of rich resource availability, shaping the regional patterns of agriculture, industry, trade, and employment. From the glacier-fed rivers of the Himalayas and the fertile alluvial plains of the Indo-Gangetic region to the mineral-rich Deccan Plateau and the resource-abundant coastal belts, each physical region contributes uniquely to national development. Often, the presence of resources influences the distribution of industries—for example, mining belts foster steel and energy industries, while fertile plains support large-scale agriculture and food-processing sectors.

Agriculture remains the backbone of India’s economy, and its performance is deeply tied to the quality of soil, water availability, and climatic conditions. The alluvial soils of the northern plains support extensive cultivation of wheat, rice, sugarcane, and pulses, providing food security for millions and sustaining rural livelihoods. In contrast, the black cotton soils of the Deccan Plateau are ideal for cotton, oilseeds, and millets. Yet agriculture also faces challenges—declining soil fertility, water scarcity, erratic rainfall, and increasing demand for sustainable practices. Climate-smart agriculture, irrigation efficiency, and soil conservation measures are becoming essential to protect this resource-driven sector.

India’s mineral wealth significantly influences its industrial growth. States like Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, and Goa are major hubs of coal, iron ore, bauxite, limestone, and manganese. These minerals power India’s steel industry, cement production, power generation, and manufacturing networks. Mining activities support millions of jobs and contribute to export revenues, but environmental degradation—land disturbance, water pollution, and deforestation—poses long-term economic risks that demand responsible management and rehabilitation.

Coastal and marine resources also play a crucial role in strengthening India’s economy. With a coastline stretching over 7,500 kilometers, India benefits from thriving fisheries, maritime trade, port-based industries, and tourism. Mangroves, coral reefs, and marine biodiversity support ecological balance and protect coastal communities, acting as natural barriers against storms and erosion. However, rising sea levels, salinity intrusion, overfishing, and coastal degradation threaten these fragile ecosystems and the livelihoods they sustain.

Energy resources are another pillar of economic development. Coal, petroleum, and natural gas fuel industrial growth, while hydropower, solar, and wind energy are rapidly emerging as sustainable alternatives. India’s renewable energy sector is expanding at a remarkable pace, bringing technological innovation, employment opportunities, and environmental benefits. Solar irrigation, decentralized energy grids, and wind farms are transforming energy access, particularly in rural regions.

Ultimately, while India is rich in natural resources, long-term economic stability depends on how wisely these resources are managed. Balancing extraction with conservation, empowering local communities, promoting scientific resource governance, and implementing environmentally sensitive policies are essential steps toward a sustainable and inclusive future. Natural resources are not merely assets—they are the key to India’s development, resilience, and prosperity in the decades ahead.

Environmental Challenges and Conservation Measures

India’s vast geographical diversity brings with it a wide range of environmental challenges that are shaping both ecological balance and human wellbeing. From rapidly melting Himalayan glaciers and polluted northern rivers to land degradation in mining-intensive plateau regions and rising sea levels along the coasts, the nation faces multiple layers of ecological stress. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and unsustainable development practices have intensified pressure on natural resources. Groundwater depletion in many states, shrinking forest cover, and habitat fragmentation have further weakened ecological resilience, affecting climate patterns, biodiversity, and livelihoods.

Pollution remains one of the most pressing concerns. Major metropolitan cities struggle with severe air pollution, leading to respiratory illnesses and reduced quality of life. Water pollution is equally alarming: rivers such as the Ganges and Yamuna receive industrial effluents, untreated sewage, and plastic waste, creating hazardous conditions for both humans and aquatic ecosystems. Soil degradation caused by excessive chemical fertilizers, pesticide use, and erosion threatens agricultural productivity and long-term food security. Combined, these issues form a complex grid of environmental pressures that require coordinated action.

Climate change has amplified these vulnerabilities. Irregular monsoons, prolonged droughts, sudden cloudburst events, intense cyclones, and extreme heatwaves are becoming increasingly frequent. Mountainous regions face landslides, glacial lake outburst floods, and erratic snowfall, while coastal communities confront saltwater intrusion, storm surges, and disappearing shorelines. In the Himalayas, shrinking glaciers pose long-term risks to river systems, which in turn affect agriculture, drinking water supplies, and hydropower generation.

To address these challenges, India is adopting a range of conservation and adaptation strategies. Forest preservation and large-scale afforestation programs play a vital role in carbon sequestration, soil stabilization, and biodiversity protection. Water conservation measures—such as rainwater harvesting, lake restoration, wetland protection, and river rejuvenation projects—are essential to improving water security. Traditional water systems like stepwells, johads, and community ponds continue to contribute to groundwater recharge, especially in rural regions.

Pollution control requires strict environmental regulations, widespread adoption of clean energy, and improved waste management. In urban areas, increasing green spaces, urban forests, sustainable transport systems (such as electric buses and cycle lanes), and climate-responsive drainage networks can significantly enhance climate resilience. Community-led initiatives, including river clean-up campaigns, citizen biodiversity groups, and village-level water management committees, are creating decentralized yet powerful models of conservation.

Ultimately, environmental challenges are not simply technical problems—they are deeply social, economic, and cultural issues. Sustainable development requires collaboration between governments, industries, local communities, and informed citizens. Environmental education, data-driven policy-making, and recognition of traditional ecological knowledge form the pillars of a resilient future. Protecting the environment is not merely an obligation; it is a shared responsibility toward preserving the planet for generations to come.

Conclusion — A Path Forward and Our Shared Responsibility

India’s physical geography is far more than a collection of landforms—it is the foundation on which our culture, economy, and daily life are built. From the towering Himalayas to the expansive plains and vibrant coastlines, every region teaches us valuable lessons about resilience, diversity, and balance. Today, challenges like climate change, resource depletion, pollution, and unplanned development stand before us, demanding thoughtful and collective action. Yet these challenges also present opportunities to rethink our relationship with nature and to build systems that are sustainable, equitable, and innovative. Conservation is not just the job of governments or organizations; it is a responsibility shared by every citizen.

By using our natural resources wisely, protecting our rivers, conserving water and energy, and embracing eco-friendly practices, we can leave behind a healthier planet for future generations. India’s landscapes remind us that progress and preservation can go hand in hand when guided by awareness, science, and community participation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the major physical regions of India?

India is divided into five major physical regions: the Himalayan Mountains, the Northern Plains, the Peninsular Plateau, the Coastal Plains, and the Island groups. Each region has unique landforms, climate patterns, and natural resources.

2. How do the Himalayas influence India’s climate?

The Himalayas block cold winds from Central Asia, guide the monsoon winds, and act as the source of major rivers. This helps regulate India’s climate, making it suitable for agriculture and human settlement.

3. Why are the Gangetic Plains so fertile?

The Gangetic Plains are formed by nutrient-rich alluvial soil deposited over thousands of years by Himalayan rivers. Regular flooding, abundant water supply, and a stable climate make this region ideal for agriculture.

4. What is causing water scarcity in many parts of India?

Irregular monsoons, over-extraction of groundwater, pollution, and rapid population growth are major causes of water scarcity. Poor urban drainage and waste management also worsen the situation in cities.

5. What environmental risks do coastal regions face?

Coastal areas face rising sea levels, storm surges, cyclones, erosion, and saltwater intrusion. These threats endanger ecosystems, fisheries, tourism, and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

6. Why is sustainable use of natural resources important?

Overuse of natural resources leads to soil degradation, water shortages, deforestation, and pollution. Sustainable management ensures long-term ecological balance and supports stable economic growth.

7. How is climate change affecting India?

Climate change is contributing to erratic rainfall, prolonged droughts, severe floods, heatwaves, and melting glaciers. These impacts affect agriculture, water availability, public health, and infrastructure.

8. What can individuals do to support environmental conservation?

Individuals can conserve water and energy, reduce plastic use, plant trees, segregate waste, and support community-based conservation efforts. Spreading awareness and adopting eco-friendly habits also make a big difference.

References / Sources

The information presented in this article is based on credible and authoritative sources related to India’s geography, climate, and environment. Key references include reports from the Geological Survey of India (GSI), the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, and the National River Conservation Programme (NRCP). Additionally, academic studies, research papers, NITI Aayog documents, and NCERT Geography textbooks have been used to ensure accuracy and reliability.

These sources collectively provide factual insights into India’s physical features, natural resources, environmental challenges, and conservation efforts.