Many times, history is perceived merely as a collection of dates and events. But for me, it is not just the study of the past — it is a living journey that flows with time. When I first studied the subject “Source Materials of Indian History” at the university, I realized that history doesn’t live only in books — it breathes beneath the soil, in the inscriptions carved on stones, and in the verses of ancient poets.

My history teacher once said — “If you truly wish to know India, read its sources and listen to its voices.” From that day onward, I began my journey — to understand India through its own evidence.

The Discovery of Ancient Indian Sources

The history of India begins from an age when there were no written words, yet humankind left behind signs of its civilization. Those signs later became what we call the “sources of history.”

1. Archaeological Sources

During my studies, when I first learned about the “Harappan Civilization,” it was thrilling to imagine that nearly five thousand years ago, our ancestors lived in well-planned brick cities.

The Discovery of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro

When I saw photographs of the Harappan excavations — the streets, drains, and the Great Bath — it felt as if time itself had turned into stone. Artifacts unearthed from Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, Lothal, and Kalibangan — pottery, seals, and toys — speak volumes about the society, religion, and economy of that era.

As a student, when I visited the National Museum in Delhi and saw the clay figurines of Harappa, a thought struck me — “Did they dream just like we do?” That human aspect of history always fascinated me.

2. Literary Sources

India’s history is not just carved on stones; it is also written in words. Our Vedas, Upanishads, Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Buddhist-Jain scriptures are living records of our civilization.

Vedic Literature

From the Rigveda to the Atharvaveda, these texts are not only religious but also depict the political and social life of early India. The mention of “Sabha” and “Samiti” in the Rigveda reveals the political structures of that time. Whenever I read Vedic hymns, I could sense the reflection of nature, philosophy, and humanity that connected me deeply with the past.

Epics — The Ramayana and the Mahabharata

One evening, as I was reading the Ramayana with my father, he said, “Son, this is not just a story; it is the history of our culture.” That day, I realized that Valmiki didn’t merely narrate the life of Rama but expressed the soul of Indian civilization in words.

Similarly, while studying the Mahabharata, the principles of “Rajdharma” and “Nyaya” introduced me to the moral and administrative foundations of India that still influence modern governance.

Buddhist and Jain Texts

The “Tripitaka,” “Anga,” “Upanga,” and Jain “Agamas” are not just religious texts; they provide insights into the society, trade, education, and position of women during their time.

In the university library, when I read the English translation of the “Majjhima Nikaya,” I discovered in Buddha’s words a deep compassion and wisdom that are still relevant to the fabric of our society today.

3. Epigraphic Records

Inscriptions, copper plates, and pillar edicts are among the most concrete proofs of Indian history. They transform history into “living documents.”

Ashokan Inscriptions

My journey once took me to Daungarh in Bihar, where one of Ashoka’s edicts was found. The echo of “Dhamma” inscribed in those letters could still be felt in the air. Reading those Brahmi letters, it seemed as if Ashoka himself was saying — “History is not only the tale of kings but the spirit of welfare for all.”

The edicts of Ashoka not only depict his moral governance but also lay the foundation of India’s administrative ideals.

Copper Plates and Pillar Records

Gupta and Chalukya-era copper plate grants provide details about donations, administration, and land systems. During my research on the “Nalanda Copper Plate,” I realized from the Sanskrit verses how deeply education and religion were intertwined in that age.

4. Numismatic Sources (Coins)

When I first saw punch-marked Mauryan coins in a museum, I was amazed to learn that each symbol carried a distinct meaning. Coins were not just economic tokens but representations of authority, religion, and art.

The gold coins of the Gupta period are particularly exquisite — with royal portraits on one side and divine symbols on the other — a true embodiment of the golden age of Indian history.

5. Accounts of Foreign Travelers

Another fascinating window to history opens when we see India through the eyes of foreign travelers. When I read “Indica” by Megasthenes, his description of Pataliputra’s administration astonished me. The Chinese travelers “Faxian” and “Xuanzang” offered invaluable accounts of Buddhist India.

Their writings remain among the most crucial sources for reconstructing India’s ancient history.

My Learnings from These Historical Sources

While studying these varied sources, I realized that Indian history is not a single narrative but a symphony of countless voices, symbols, and philosophies. Every brick, every manuscript, and every inscription is a living testimony of our past.

Sometimes, as I sit in my study, I feel as if these sources are whispering to me — “Read us, understand us, for your present stands upon the foundation we built.”

Medieval Indian Sources

After completing my study of ancient Indian sources, I realized that the journey of history does not end there. The past of India is like a flowing river — beginning from the Indus Valley, passing through the Vedic age, Mauryan and Gupta empires, and then entering the medieval period — each era adding new layers of culture and wisdom.

During my research work, I traveled to historic cities such as Delhi, Ajmer, and Jodhpur. The inscriptions on the walls of mosques, forts, and dargahs, the Persian manuscripts, and the rhythm of folk songs — all revealed to me glimpses of that era we now call “Medieval India.”

1. Persian and Arabic Sources

The richest sources of medieval Indian history are those written in Persian. When Muslim rulers arrived in India, they brought with them the tradition of chronicling history. These works are not merely political narratives but mirrors reflecting the social, religious, and administrative life of that age.

Court Historians and Their Works

Once, at my university, I attended a seminar on Persian historiography. That was the first time I heard in detail about Minhaj-us-Siraj’s Tabaqat-i-Nasiri and Ziauddin Barani’s Tarikh-i-Firuzshahi. These chronicles vividly describe the Delhi Sultanate’s administrative systems, religious policies, and social structures.

When I read Barani’s writings, his philosophical perspective struck me deeply — a historian is not just a witness to events, but also a carrier of ideas.

Abul Fazl and the Akbarnama

During the Mughal era, Abul Fazl’s Akbarnama and Ain-i-Akbari elevated historical writing to new intellectual heights. When I read the first volume of Ain-i-Akbari, it felt as if I were sitting in Akbar’s grand court — among scholars, artists, musicians, and soldiers who together were shaping a new civilization.

Abul Fazl’s writing is not mere praise of an emperor; it presents a vivid portrayal of India’s geography, economy, administration, and religious tolerance. His intellectual breadth and organizational insight still inspire me today.

Other Persian Chronicles

Firishta’s Tarikh-i-Firishta, Nizamuddin Ahmad’s Tabaqat-i-Akbari, and Badauni’s Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh offer diverse perspectives on politics, culture, and religion in medieval India. They remind us that history changes depending on who is telling the story.

2. Sanskrit and Regional Texts

During the same period, the tradition of Sanskrit literature continued to thrive. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini — a poetic chronicle of Kashmir’s kings — combines literary beauty with historical truth. As I studied this work, I could almost visualize a civilization flourishing among lakes and mountains.

Meanwhile, historical and heroic ballads also developed in Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, and Tamil. Texts like Prithviraj Raso, Hammir Raso, and Pabuji Ki Phad are not merely poems — they are cultural reflections of Rajasthan’s valor, faith, and social identity.

Rajasthani and Folk Traditions

The folk traditions of Rajasthan have always fascinated me. When I visited villages near Jhunjhunu and Nagaur, I met folk artists who sang ballads of Tejaji, Gogaji, and Pabuji. I realized that history does not only survive in books — it lives in the memories of people.

These ballads do not just narrate bravery; they preserve moral values, struggles, and faith. The folk tradition has kept history connected with common life — and that is its greatest strength.

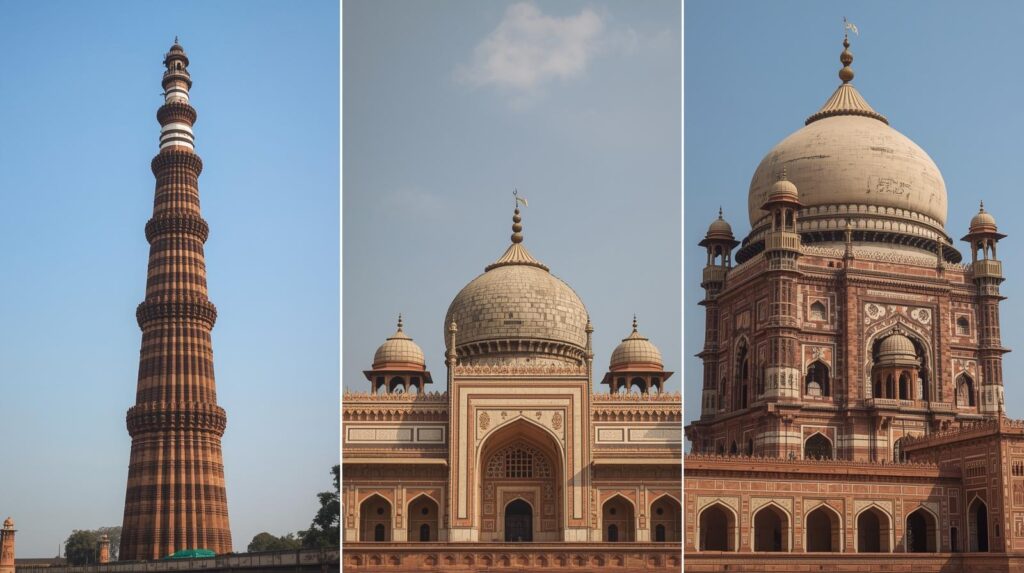

3. Architectural and Artistic Sources

Architecture is another vital source for understanding medieval Indian history. The Qutub Minar in Delhi, Adhai Din Ka Jhopra in Ajmer, Buland Darwaza at Fatehpur Sikri, and the Taj Mahal at Agra — these monuments are not just examples of art, but symbols of political power and cultural dialogue.

When I first visited Fatehpur Sikri, the red sandstone walls seemed to whisper stories of time. Standing inside Akbar’s “Ibadat Khana,” I realized that intellectual diversity was as alive then as it is today.

Painting and Sculpture

Mughal miniature paintings, Rajput art, and Pahari paintings are visual sources that express the emotions of history through colors. Once, in Jaipur’s City Palace Museum, I saw an Akbar-era painting depicting scholars in discussion — and in that artwork, I saw the living beauty of history itself.

4. Epigraphic and Inscriptional Sources

The tradition of inscriptions continued during medieval India as well. Temple and dargah walls, copper plates, and stone slabs carried records of donations, trade, and religious structures.

In the Jain temples of Ranakpur and Mount Abu, inscriptions reveal the economic structures and trade guilds of that time. Reading them, I realized how deeply religion and economy were interlinked.

5. Accounts of Foreign Travelers

The writings of foreign travelers provide another valuable window into medieval India. The journeys of Ibn Battuta — who served in Muhammad bin Tughlaq’s court — have always amazed me. His descriptions of Delhi’s streets, markets, and governance are more vivid than any contemporary source.

Similarly, Portuguese traveler Duarte Barbosa and French traveler François Bernier recorded detailed observations on India’s economy, caste system, and administration — invaluable for reconstructing the era.

Lessons from Medieval India

The sources of medieval India taught me that history is not just the story of conquerors; it is a journey of dialogue, coexistence, and cultural synthesis. Between Persian and Sanskrit texts, between temples and mosques, and in the melodies of folk songs — there exists an India that stands as living proof of unity in diversity.

Even today, when I touch the walls of an old fort, I feel the warmth of history within the dust of time. These sources are not merely relics of the past — they form the very foundation of our national character.

Modern Indian Sources

As my study progressed beyond the forts and poems of medieval India, time led me into an era where India stood at the threshold of a new age — Colonial India.

This was the period when the pen, paper, and print press began to write new chapters of history. History was no longer only the saga of kings and rulers; the voices of the common people — peasants, workers, and students — began to echo as well.

The first time I visited the National Archives in Delhi, the smell of those yellowing files made me feel the dampness of the past. Every file, every letter, every report was a new witness to history.

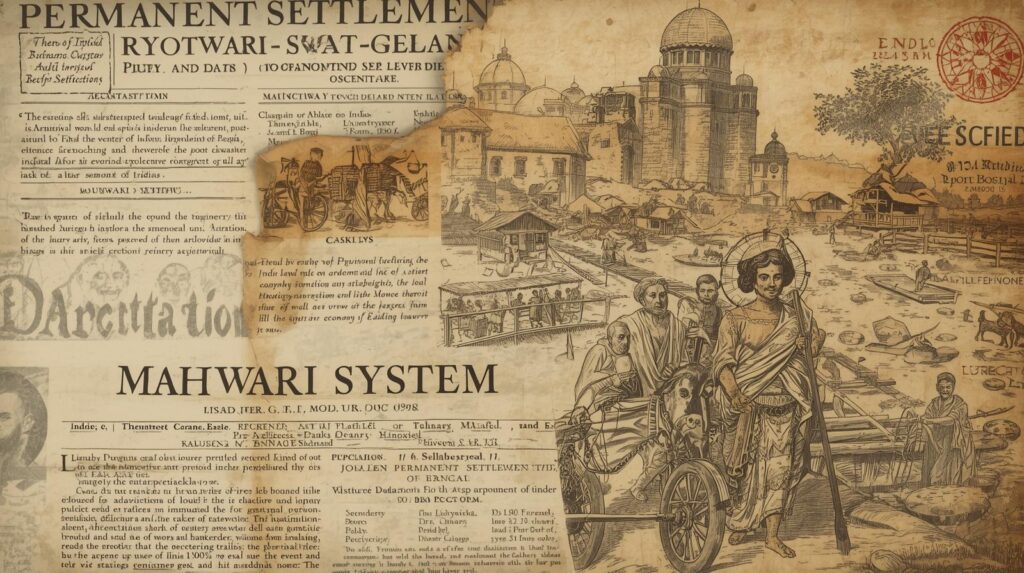

1. Colonial Administrative Records (British Administrative Records)

In the British period, the largest form of historical sources emerged as official documents. The British recorded everything in writing — land, revenue, population, law, trade, even education and religion.

Revenue and Land Records

Reports on the Permanent Settlement, the Ryotwari system, and the Mahalwari system are available to us in great detail today. When I read the reports on the Permanent Settlement in Bengal, the harsh realities of the peasant’s life became painfully clear.

These records show how colonial policies shaped the structure of Indian agriculture, society, and economy.

Census Reports

The British began conducting regular censuses from 1871. These reports document not only population counts but also caste, religion, occupation, and education.

During one of my research projects I studied the 1901 census report. The figures recorded there revealed how colonial policies gradually divided society into categories and communities. This data remains invaluable for historians even today.

Legal and Administrative Documents

Acts like the Indian Penal Code (IPC), the Indian Evidence Act, and court proceedings reflect the judicial and administrative thinking of that time.

When I studied records related to court proceedings, I observed the tensions between social values and the British legal framework.

2. English and Indian Newspapers

A second major source for modern history is newspapers.

When newspapers like the Bengal Gazette and Amrita Bazar Patrika began in the nineteenth century, the voice of the Indian public was recorded on paper for the first time. These papers did more than report news; they raised social consciousness.

While working on a university project, I read issues of The Hindu and Kesari from the 1880s. The passion and self-respect in Tilak's writings gave me a new understanding of the meaning of freedom.

Editorials and Opinion

The editorials in these newspapers vocally criticized colonial policies. They became not only spokesmen for political movements but also instruments of public awakening.

It was inspiring to see how a simple printing press could challenge the foundations of British rule.

3. Private Letters, Diaries, and Autobiographies

Among all sources, private letters and autobiographies revealed the most human dimensions to me.

Letters of Leaders and Reformers

Letters of Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru’s Discovery of India, Subhas Chandra Bose’s diaries, and Sarojini Naidu’s personal correspondences — these writings pulse with the heartbeat of history.

They are documents not only of political events but of emotions, struggles, and ideals.

I remember reading a letter in which Gandhiji wrote, “Truth alone is God.” That single sentence made me realize that history is not only about ideologies but also about the soul.

Autobiographical Sources

Autobiographies like Gandhi’s, Nehru’s, and Tagore’s biographies provide deep insights into the socio-political life of modern India.

Reading these accounts feels as if time itself is speaking through personal experience.

4. Documents Related to the Freedom Movement

Documents connected to India’s freedom struggle are among the most inspirational sources of modern history. Proceedings of Congress sessions, resolutions, and leaders’ speeches — these are the memories of our national struggle.

All-India Congress Records

These documents show the evolution of India’s political consciousness — from petition-based movements and the Swadeshi movement, to non-cooperation, and finally the demand for full independence.

I once read an original report about the 1930 Salt Satyagraha — it said, “When salt was made on the shores of Dandi, not only a law was broken, but the chains of slavery also began to melt.”

That sentence taught me that documents can sometimes sow the seeds of revolution.

Revolutionary Records

Bhagat Singh’s jail diary, correspondence of the Anushilan Samiti, and records of the Indian National Army — these are the voices of colonial India’s youth.

Reading these documents felt as if history had not merely been written but lived.

5. Cultural and Educational Sources

During the British period, sources related to education, literature, and culture also gained great importance.

University and Institutional Records

The founding of the universities of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay ushered in a new era of education. Their annual reports and curricula today reflect the intellectual thinking of the time.

When I read the 1885 annual report of Calcutta University, it stated, “The purpose of education in India should not be merely employment, but the development of citizenry.” That line remains a guide for me.

Literary Sources

Modern Indian literature — works by Premchand, Tagore, Subhadra Kumari Chauhan, and Keshav Chandra Sen — serves as social history.

Novels and poems like Godaan, Gitanjali, and writings on figures like the Rani of Jhansi express the era’s social injustices, nationalism, and awakening.

My Learnings from Modern Indian Sources

Studying all these sources made me realize that history is not merely a tale of the past but the foundation of the present. British administrative records warn us, newspapers inspire us, and the documents of freedom fighters fill us with pride.

As a researcher I felt that every document — whether official or personal — carries within it an emotion, a perspective, and a struggle.

Even today, when I open an old file, it feels as though it is telling me — “We are not history; we are your identity.”

Interpretation and Lessons of History

My journey through history was now almost complete — from the soil of the Indus Valley to the archives of Delhi, from the ancient Vedas to modern newspapers. But the closer I moved toward the past, the more I realized that history is not merely a record of dates and events — it is the mirror of human consciousness.

Every era expressed itself in its own way — some through stone, some through paper, and others through words. And I, as a student, tried to listen to all these voices — because history is not something to be memorized; it is something to be understood.

1. Interpretation of History — Perspective and Truth

As I studied different sources, it became clear that history is never uniform. Every source is bound by its own context and perspective.

For example, Ashoka’s edicts interpret “Dhamma” from the perspective of a moral ruler; Abul Fazl’s works reflect Akbar’s policies through the eyes of a court intellectual; and British records portray India as a colony, whereas Indian newspapers present it as an awakening nation.

That is the beauty of history — it is not built from one viewpoint but from many.

Objectivity and Emotion in History

I realized that while reading history, knowing facts is not enough; one must understand the emotions and circumstances behind them. When I read Gandhi’s letters, it was not just words I heard — it felt as if a soul was speaking. When I read Ashoka’s inscriptions, I could sense the echo of compassion carved into the stone.

History teaches us that truth doesn’t only exist on paper — it also lives within human experience.

2. History as Education

As a student, I found that history is not merely a subject to pass an exam, but a guide to living life. It teaches us that civilizations rise and fall, rulers come and go — but values and ideas endure forever.

Lessons Learned from History

- Humility — because every civilization, no matter how great, can decline.

- Tolerance — because diversity is India’s true strength.

- Search for Truth — because the essence of history lies in the journey toward truth.

- Sense of Duty — because every generation is responsible for its own time.

When I teach history to students, I often say — “History is not something to memorize, but an art of thinking.”

3. History and Modern Awareness

In today’s age of information overload, history teaches us wisdom. It reminds us that every piece of information has a context, every fact has a background.

When I studied modern sources — newspapers, journals, and digital archives — I understood that we are still writing history today. The only difference is the medium — where once we had stone and copper plates, now we have the internet and data servers.

Yet the purpose remains the same — to preserve the memory of our civilization.

History and National Identity

History also teaches us that our national identity is built not just on geography, but on memory and culture. The soul of India resides in its sources — in the hymns of the Vedas, the edicts of Ashoka, the walls of Fatehpur Sikri, and the documents of independence.

When I see all these sources together, it feels as if they together compose a living scripture called “India.”

4. My Personal Learnings

The study of history gave me not just knowledge of the past, but depth in life itself.

I remember once visiting an ancient temple near Jhunjhunu, where old inscriptions were carved on the walls. When I touched them with my fingers, it felt as though time was flowing through me.

History taught me that while people change and eras evolve, the values of truth, compassion, and wisdom remain eternal.

Today, when I open an ancient manuscript or stand before a historical monument, it feels as if — “I am not reading history; history is reading me.”

5. The Importance of History — A Final Reflection

History is the mirror of our society, and source materials are the light that makes that mirror visible. Without them, we cannot see ourselves clearly.

The remains of ancient civilizations, the chronicles of the medieval era, and the modern documents — all tell us who we were, where we came from, and where we are heading.

For me, history is not just the “past,” but a “living consciousness.” It reminds me every day that the foundation of the present was laid in the past — and the direction of the future depends on how well we understand it.

Conclusion — The Living Spirit of History

When I look back, I realize that this journey through history was actually a journey of self-discovery.

The source materials of Indian history — soil, inscriptions, scriptures, records, and words — all come together to form an eternal dialogue.

I have learned from history that time never stops; it always moves forward, teaching something at every moment. Those who understand their history make their present meaningful and their future bright.

And perhaps that is why, whenever I turn the page of an old document, one thought echoes in my mind — “History is not a thing of the past; it is the heartbeat of our existence.”