Introduction

The Himalayas evoke images of towering snow-capped peaks, remote valleys, and a landscape that both humbles and inspires. Far from being a single ridge, this mountain complex is a mosaic of parallel ranges, glaciers, river systems, and culturally rich valleys that together form the backbone of South and Central Asia. The Himalayas influence regional climate patterns, store vast quantities of freshwater in their glaciers, and support diverse ecosystems and human communities across multiple countries.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Geologically, the Himalayas were created by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates — a slow but relentless force that has uplifted these mountains over tens of millions of years and continues to make the region seismically active today. This process has produced a striking variety of rock types, folded strata, and high-relief landscapes that shape local weather, hydrology, and natural hazards such as landslides and earthquakes.

Ecologically, the Himalayas contain dramatic altitude-driven shifts: from subtropical foothill forests to temperate woodlands, alpine meadows, and permanent ice fields. These zones host many endemic and endangered species and sustain agricultural systems, medicinal-plant traditions, and pastoral livelihoods. Hydrologically, Himalayan glaciers and snowfields act as the continent’s “water towers,” feeding major rivers like the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus that millions depend on for irrigation, drinking water, and hydropower.

Culturally and spiritually, the mountains are equally significant: sacred peaks, pilgrimage routes, monasteries, and living traditions reflect the deep human connections to these landscapes. Yet the Himalayas face mounting pressures from climate change, unplanned infrastructure, tourism, and resource extraction. This article aims to offer a balanced introduction to the major Himalayan ranges, their ecological and cultural importance, and the conservation challenges we must address to protect this vital mountain system for future generations.

Brief Introduction to the Himalayas

The Himalayas are one of the world's most important mountain systems, stretching across several countries and forming a vast geological, ecological, and cultural backbone for South and Central Asia. Formed by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, this immense range contains some of the planet's highest summits—including Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga—and spans roughly 2,400 kilometers from west to east. Rather than a single ridge, the Himalayas comprise multiple parallel ranges and sub-ranges with distinct geological structures and histories.

Himalayan glaciers and seasonal snowfields function as natural water towers that feed major rivers such as the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus. These rivers sustain agriculture, provide drinking water to millions, and support hydropower and economic activity across the plains below. The steep altitudinal gradients produce diverse ecosystems — from subtropical forests and riverine lowlands to temperate woodlands, alpine meadows, and permanent ice — creating habitats for many endemic and specialized plant and animal species.

Beyond physical geography, the Himalayas hold profound cultural and spiritual significance. Mountain communities maintain unique languages, agricultural practices, and traditional knowledge shaped by long experience in high-altitude environments. Pilgrimage routes, monasteries, and sacred landscapes are integral to regional identities and religious life. At the same time, the region confronts pressing environmental and social challenges: rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, glacier retreat, expanding infrastructure, and tourism pressures that together increase exposure to landslides and glacial lake outburst floods.

Understanding the Himalayas therefore requires an integrated perspective that links geology, ecology, livelihoods, and governance. Protecting these mountain systems is essential not only for conserving fragile ecosystems but also for sustaining water and food security for vast downstream populations. In the sections that follow, this article explores the major Himalayan sub-ranges, highlights key ecological and cultural features, and outlines practical conservation and adaptation approaches to enhance resilience and support communities dependent on mountain resources.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Geographical Overview

The Himalayan region is one of the most complex and dynamic mountain systems on Earth, shaped primarily by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. This immense geological event, which began around 50 million years ago and continues today, pushed up layers of rock to create the towering ranges that form the Himalayas. Geographically, the Himalayas are commonly divided into three major belts: the Great Himalaya, which contains the highest peaks such as Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga; the Middle or Lesser Himalaya, characterized by rugged valleys and forested slopes; and the Trans-Himalaya, an arid, high-altitude zone featuring plateaus and cold deserts.

Spanning more than 2,400 kilometers in length, the Himalayas stretch across five countries—India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Pakistan. Their width varies significantly from region to region, ranging between 200 to 400 kilometers. With increasing altitude, extreme variations in temperature, precipitation, vegetation, and wildlife become evident. The southern slopes receive abundant monsoon rainfall and support dense forests, while the northern flanks lie in the rain-shadow zone and experience cold, desert-like conditions.

The Himalayan glaciers are central to the region’s geographical significance. Often referred to as the “Water Tower of Asia,” these glaciers feed major river systems including the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus. These rivers support agriculture, renewable energy, drinking water supplies, and transportation networks for hundreds of millions of people. However, the same geography that provides life-sustaining water also creates natural hazards: steep gradients, active erosion, and rapid snowmelt contribute to landslides, flash floods, avalanches, and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), making the region highly vulnerable to climate and seismic disturbances.

From a geological perspective, the Himalayas are composed of diverse rock formations, including metamorphic, igneous, and sedimentary rocks that reveal a rich history of tectonic uplift, folding, and faulting. The region is one of the most active seismic zones in the world, with frequent earthquakes of varying intensities. These seismic activities highlight the need for careful planning, resilient infrastructure, and disaster preparedness among the communities living in these fragile landscapes.

Ultimately, the geographical overview of the Himalayas goes far beyond physical features. It encompasses the interconnected layers of climate systems, ecological networks, hydrological cycles, and human settlements. The following sections will explore each major sub-range in detail, analyze the ecological and cultural dimensions of Himalayan geography, and highlight the challenges posed by climate change, development pressures, and environmental degradation.

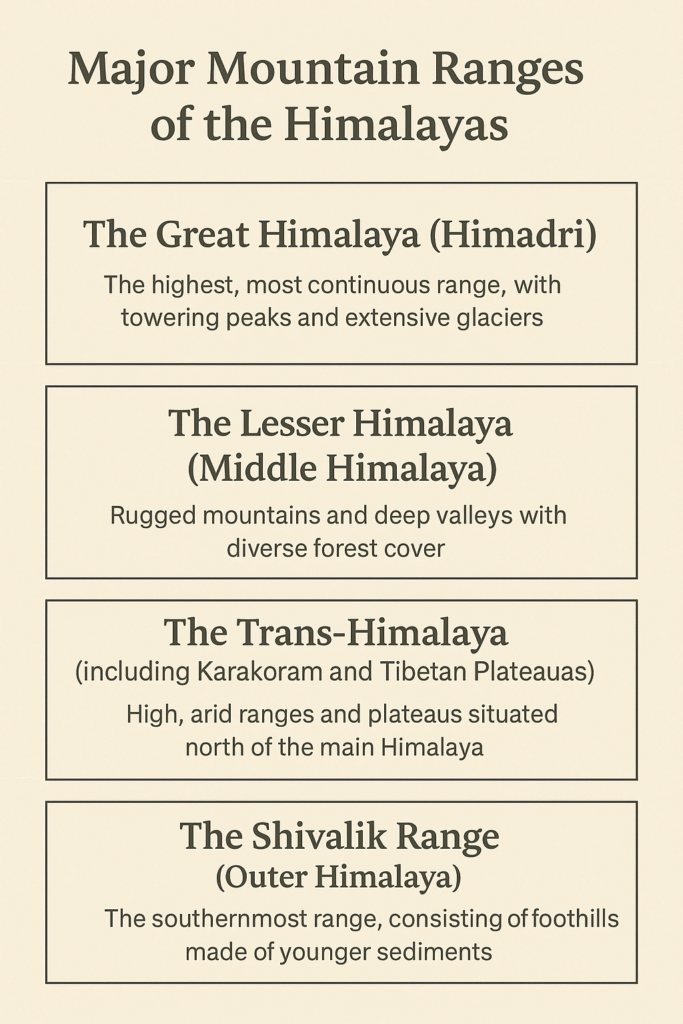

Major Mountain Ranges of the Himalayas

The Himalayan mountain system is not a single uniform ridge but a complex assembly of parallel ranges and subsidiary belts, each with its own geology, climate, ecology, and human history. In this section we examine four principal sub-systems—focusing on their physical character, major peaks and glaciers, ecological importance, and human dimensions. The aim is to present a balanced, descriptive account that helps readers appreciate why each range matters to water security, biodiversity, culture, and regional development. Following the individual range profiles, readers will gain a clearer picture of how these ranges interlock to form the Himalayan mosaic.

1. The Great Himalaya (Himadri)

The Great Himalaya, commonly called the Himadri, is the highest, most continuous, and most glaciated of the Himalayan belts. Stretching roughly along the axis of the mountain system, it contains the world’s tallest peaks—Mount Everest, Kanchenjunga, Lhotse, Makalu, and many others—that rise above 7,000–8,000 meters. These massive summits are capped by permanent snowfields and massive valley glaciers which feed the headwaters of Asia’s great rivers. The Great Himalaya acts as the primary “water tower” for South Asia: glaciers and seasonal snowmelt regulate river flows that support downstream irrigation, hydropower and drinking-water supplies for tens of millions of people.

Geologically, the Himadri comprises high-grade metamorphic rocks, ancient gneisses and intruded granites that have been profoundly deformed and uplifted by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates. The tectonic forces that created this belt are ongoing, making the region seismically active and structurally complex. The steep relief and fragile soils also make the range susceptible to mass wasting—avalanches, rockfalls and deep-seated slope failures—especially where permafrost degradation and glacial retreat destabilize formerly frozen slopes.

Ecologically, the Great Himalaya supports a narrow but unique set of high-altitude habitats: sparsely vegetated alpine meadows, cushion plants, dwarf shrubs, lichens and cold-tolerant herbs. Faunal specialists—snow leopards, Himalayan blue sheep (bharal), Himalayan tahr and several alpine bird species—are adapted to the harsh environment. The limited carrying capacity of these ecosystems means that even modest human pressures—high-altitude tourism, waste accumulation at base camps, or unregulated grazing—can have outsized impacts on flora and fauna.

Culturally and spiritually, many sites in and near the Great Himalaya are revered—Mount Kailash and sacred lakes, ancient pilgrimage routes, and monasteries anchor local belief systems. Economically, the upper belts contribute seasonal pastures, high-altitude medicinal plants and specialized tourism income, while posing logistical challenges for infrastructure development. As climate warming accelerates, the Great Himalaya’s glaciers are retreating and the nature of snowmelt-driven flows is changing; this creates near-term risks of glacial-lake outburst floods (GLOFs) and long-term concerns for water security, demanding coordinated scientific monitoring and community preparedness across national boundaries.

2. The Lesser Himalaya (Middle Himalaya)

The Lesser Himalaya—often referred to as the Middle Himalaya or Himachal belt—lies south of the Great Himalaya and north of the Shivaliks. With typical elevations between roughly 1,500 and 4,500 meters, this belt is characterized by rugged mountains, deeply incised valleys, intermontane basins and extensive forest cover on favorable slopes. Rock types here include folded sedimentary sequences and metamorphic strata that are more weathered and erodible than the harder rocks of the Himadri; this contributes to active slope processes and frequent landslides, particularly where steep slopes are intersected by monsoon runoff.

The Lesser Himalaya is ecologically richer than the uppermost zones: broadleaf forests, temperate conifers, rhododendron stands and mixed woodlands support diverse wildlife—leopards, black bears, Himalayan langurs, and a host of bird species. The altitudinal range makes it particularly important for agro-ecological systems: terrace farming, orchards, and high-value horticulture (apples, nuts, medicinal herbs) thrive on mid-elevation slopes and plateaus. Rural settlements and historical hill towns such as Shimla, Darjeeling (on adjoining ranges), and many Nepali towns are located within this belt, making it a cultural and economic interface between high mountain pastures and the plains.

From a human perspective, the Lesser Himalaya is a zone of intensive land use: roads, hydro projects, tourism infrastructure and agriculture all converge here. This creates both opportunities and hazards—improved connectivity and livelihoods on one hand, and increased erosion, habitat fragmentation and disaster risk on the other. Sustainable land management, slope stabilization measures, and community-based forest management are therefore especially important in the Lesser Himalaya to balance development and ecological resilience.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

3. The Trans-Himalaya (including Karakoram and Tibetan Plateaus)

The Trans-Himalaya refers to the high, often arid ranges lying north of the main Himalayan axis. This category encompasses the Ladakh Range, parts of the Karakoram, and the high Tibetan Plateau margin. Elevations commonly exceed 4,500 meters, and climatic conditions are markedly drier because the main Himalayan barrier casts a rain shadow to the north. The Karakoram—geologically distinct and home to K2 and other ultra-prominent peaks—contains some of the largest non-polar glaciers in the world and exhibits striking glacial dynamics that differ from those of the Great Himalaya.

Vegetation here is sparse and specialized—cold-steppe, shrubs, lichens and scattered grasses—supporting iconic highland fauna such as the Tibetan wild ass (kiang), Marco Polo sheep, ibex and snow leopards. Human settlements are often sparse and adapted to extreme temperatures and short growing seasons; pastoralism (yak and sheep herding), trans-Himalayan trade routes and resilient cultural traditions are hallmarks of life in these ranges. Several important transboundary watersheds originate in the Karakoram and Trans-Himalayan zones, making them crucial to downstream river dynamics despite their relative aridity.

The Trans-Himalaya is also geopolitically sensitive: borders, high passes and remote militarized regions coexist with fragile ecosystems. Glacial research in this zone has revealed complex patterns—some glaciers are retreating rapidly, while others in parts of the Karakoram have been comparatively stable, a phenomenon often called the “Karakoram anomaly.” Regardless, warming and altered precipitation regimes threaten permafrost, pasture productivity and the infrastructure that connects isolated communities. Preserving traditional livelihoods and integrating modern climate adaptation—water capture, pasture management, and disaster preparedness—are priority actions for the Trans-Himalayan highlands.

4. The Shivalik Range (Outer Himalaya)

The Shivalik Range, or Outer Himalaya, forms the southern foothills of the Himalayan system and is the youngest geological belt of the orogen. Typically 600–1,200 meters high, the Shivaliks consist largely of unconsolidated sediments, gravels and sands that erode relatively easily. Their gentle-to-moderate slopes create a transition zone between the plains and the higher mountain belts, hosting unique ecological communities and serving as a critical buffer for flood and erosion control.

Climatically the Shivaliks receive abundant monsoon rainfall on their southern flanks, enabling dense subtropical and tropical moist deciduous forests in many sections. These forests historically supported diverse wildlife—elephants in some sectors, deer, primates and many bird species—and they also provided timber, non-timber forest products, and grazing lands for local communities. Over the last decades, however, rapid urban expansion, road building, quarrying and agricultural intensification have fragmented habitats and increased sediment loads entering river systems downstream.

The Shivalik belt plays a vital hydrological role: its permeable sediments recharge groundwater aquifers that sustain wells and springs for adjacent plains and hill settlements. Yet its loose geology also makes it prone to landslides and bank erosion when vegetation is removed or drainage is altered. Conservation and sustainable planning in the Shivaliks require careful land-use zoning, regulation of mining activities, watershed management, and reforestation to restore ecological functions that protect both mountain and plain communities.

Together these four belts—the Great Himalaya, the Lesser Himalaya, the Trans-Himalaya (and Karakoram), and the Shivalik foothills—compose the major structural and ecological framework of the Himalayan region. Each belt performs distinct environmental services and faces particular hazards; effective regional stewardship therefore requires integrated planning, transboundary research, and community-led conservation to sustain the mountains and the vast populations that depend on them.

Ecology and Glaciers

The ecology of the Himalayas is one of the most diverse and fragile in the world. Due to dramatic variations in altitude, climate, and precipitation, the region supports a remarkable range of ecosystems—from subtropical forests at the foothills to temperate woodlands, coniferous forests, alpine meadows, and ultimately the icy wilderness near the highest peaks. Each ecological zone hosts distinct species of flora and fauna, many of which are rare, endangered, or found nowhere else on Earth. Iconic species such as the snow leopard, red panda, Himalayan musk deer, Tibetan wolf, and various high-altitude birds depend on these delicate habitats for their survival. Plant life includes rhododendrons, junipers, cedars, medicinal herbs, and alpine grasses that adapt to harsh climatic conditions.

Glaciers form the most critical component of the Himalayan ecological system. Often referred to as the “Water Tower of Asia,” the Himalayas contain more than 15,000 glaciers, making them the largest concentration of ice outside the polar regions. Major glaciers such as Gangotri, Yamunotri, Siachen, Zemu, and Khumbu are vital freshwater sources feeding the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Indus, and other major rivers. These rivers sustain agriculture, drinking water supplies, fisheries, hydropower generation, and the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people living downstream. The glaciers release meltwater gradually through the year, ensuring a stable supply of water even during dry seasons.

However, the rapidly changing climate poses a significant threat to Himalayan ecology and glacier systems. Rising temperatures have accelerated glacier retreat, reduced snow cover, and altered precipitation patterns. As glaciers melt more quickly, glacial lakes expand, increasing the risk of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs)—sudden, destructive floods that can wipe out villages, farmland, and critical infrastructure in moments. Declining glaciers also threaten long-term water security, particularly during summer months when river flow largely depends on meltwater.

Human activities have further increased the vulnerability of this ecosystem. Deforestation, poorly planned road construction, unregulated tourism, mining, and urban expansion disrupt natural habitats and intensify soil erosion and landslides. Many wildlife species are losing their habitats and migrating to higher altitudes in search of food and suitable climate, leading to ecological imbalance. Conservation strategies such as expanding protected areas, restoring degraded forests, managing wildlife corridors, promoting responsible tourism, and empowering local communities in resource management are now essential to safeguard the Himalayan environment.

The ecology and glaciers of the Himalayas are not just natural features; they are lifelines for an entire subcontinent. Protecting these systems is crucial for maintaining biodiversity, ensuring water security, and supporting the cultural and economic well-being of millions. As climate change intensifies, the responsibility to conserve this delicate mountain system becomes more urgent than ever. The following sections will explore cultural, social, and conservation dimensions that further highlight the significance of the Himalayan landscape.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Culture, Religious Significance, and Local Life

The Himalayas are not merely a collection of towering peaks—they are a vibrant cradle of culture, spirituality, and traditional mountain life. For thousands of years, the Himalayan region has been central to the civilizations and religious traditions of South Asia. In Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and the ancient Bon tradition, the Himalayas are revered as sacred lands. Holy sites such as Mount Kailash, Lake Mansarovar, Kedarnath, Badrinath, Amarnath, Hemkund Sahib, and numerous Buddhist monasteries are located across this majestic region. The serenity of the mountains, the purity of the rivers, and the deep sense of spiritual calm have drawn sages, monks, and seekers here for centuries.

The cultural landscape of the Himalayan states—Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Ladakh, Nepal, and Bhutan—is exceptionally diverse. Each community has its own language, attire, folklore, dance forms, festivals, and culinary traditions that reflect the challenges and beauty of mountain life. Despite harsh climatic conditions and rugged terrain, the people have developed sustainable ways of living that are closely tied to their natural surroundings. Terrace farming, pastoralism, wool weaving, traditional handicrafts, and local trade form the backbone of their economy and lifestyle.

The daily life of mountain communities is deeply intertwined with nature. Community-based traditions such as protecting sacred forests, preserving water sources, using indigenous weather knowledge, and practicing nature worship exemplify sustainable living. Festivals like Losar, Phagli, Makar Sankranti, Budi Diwali, and various harvest celebrations are rooted in agricultural cycles and local belief systems. These festivals strengthen social bonds and keep ancient cultural practices alive across generations.

However, modernization has brought noticeable changes to Himalayan societies. Urban migration, tourism-driven commercialization, infrastructural expansion, and climate impacts have altered social structures and livelihoods. Traditional skills are declining as younger generations move toward cities for opportunities. Yet, the core essence of Himalayan culture—respect for nature, community unity, spiritual depth, and simple living—remains strong. Preserving this cultural heritage is essential not only for mountain communities but also for safeguarding the rich spiritual and social tapestry of the entire subcontinent.

Adventure Activities: Trekking and Mountaineering

The Himalayas have long been a symbol of adventure, resilience, and exploration. With towering peaks, deep valleys, glaciers, and rapidly changing weather, the region offers some of the most thrilling trekking and mountaineering experiences in the world. Every route presents a unique combination of natural beauty and physical challenge, attracting adventurers ranging from beginners to elite mountaineers. Trekking and mountaineering in the Himalayas are not just outdoor activities—they are immersive journeys into nature, culture, and self-discovery.

The Himalayas host numerous famous trekking routes, each offering a different landscape and difficulty level. Popular trails include the Valley of Flowers and Roopkund trails in Uttarakhand, the Hampta Pass trek in Himachal Pradesh, the Everest Base Camp trek in Nepal, and the Snowman Trek in Bhutan. These routes allow trekkers to experience snow-covered peaks, dense forests, alpine meadows, glacial lakes, and remote mountain villages. Along the way, travelers also encounter local cultures, traditional mountain lifestyles, and breathtaking sunrise and sunset views over the ranges.

Mountaineering in the Himalayas is considered the pinnacle of high-altitude adventure. The region is home to eight of the world's fourteen 8,000-meter peaks, including Everest, Kanchenjunga, Lhotse, Makalu, and Annapurna. Climbing these giants requires advanced technical skills, physical endurance, mental strength, and expert navigation through crevasses, icefalls, rock faces, and unpredictable weather. High-altitude challenges such as low oxygen levels, extreme cold, and powerful winds make Himalayan climbs some of the toughest on Earth.

Safety and preparation are essential for any Himalayan adventure. Proper gear, trained guides, awareness of weather conditions, altitude acclimatization, emergency medical kits, and adherence to environmental guidelines are crucial for a safe experience. Following principles like “Leave No Trace” helps protect fragile ecosystems while ensuring responsible tourism. With the right preparation and respect for nature, trekking and mountaineering in the Himalayas become life-changing experiences that foster courage, patience, and a deep appreciation for the natural world.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Conservation, Challenges, and Recommendations

The Himalayan ecosystem is extremely fragile, and rapid climate change combined with increasing human activity has placed severe pressure on its stability. Rising temperatures have accelerated glacier melt, altered precipitation patterns, and increased the frequency of landslides, flash floods, and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). Deforestation, unregulated tourism, illegal mining, expanding road networks, and unplanned urban development have further intensified environmental degradation. These changes not only threaten natural habitats and river systems but also endanger the livelihoods, agriculture, and water security of millions of people living in Himalayan and downstream regions.

Conservation of the Himalayas requires long-term, science-based, and community-driven strategies. First, regulating construction and limiting unsustainable human activities in ecologically sensitive zones is essential. Protecting forests through large-scale afforestation, restoring degraded land, and strengthening wildlife corridors can help maintain ecological balance. Advanced monitoring tools—such as satellite-based remote sensing, climate modeling, and glacier mapping—are vital for identifying risks early and guiding informed policy decisions. Managing water resources efficiently and preserving wetlands and high-altitude pastures are equally important.

Engaging local communities is one of the most effective conservation approaches. Mountain communities possess traditional ecological knowledge, weather-reading skills, and sustainable resource-use practices passed down through generations. Promoting community-based tourism, environmental education, waste management systems, and climate-resilient farming can empower locals while reducing environmental impact. Encouraging principles like “Leave No Trace” and responsible travel can significantly minimize ecological pressure from tourism.

Ultimately, protecting the Himalayas requires coordinated action among scientists, policymakers, local residents, and visitors. The Himalayas are not only a source of natural beauty—they are crucial for water security, biodiversity, cultural heritage, and climate regulation across an entire subcontinent. Timely, collective, and sustainable conservation efforts will ensure that this majestic mountain system continues to thrive for future generations.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Conclusion

The Himalayas are far more than dramatic peaks: they are a complex, interdependent system that sustains water security, biodiversity, cultural traditions, and livelihoods across a vast region. Throughout this article we examined the distinct roles of the Great Himalaya, the Lesser Himalaya, the Trans-Himalayan belts (including Karakoram), and the Shivalik foothills—each contributes unique ecological services while facing specific climate and development pressures. Rising temperatures, glacier retreat, unplanned infrastructure, and unsustainable tourism are already altering hydrology, habitats, and community resilience. Addressing these challenges requires science-led monitoring, inclusive policies, and local stewardship that balance conservation with responsible development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the highest peak in the Himalayas and why is it significant?

The highest peak in the Himalayas is Mount Everest, standing at 8,848.86 meters. Located on the border of Nepal and China (Tibet), it is not only the tallest mountain on Earth but also a symbol of human endurance and exploration. Everest attracts thousands of climbers each year and plays a crucial role in Himalayan ecology by hosting glaciers that feed major rivers. Its immense cultural, ecological, and geographical relevance makes it globally significant.

2. Why are Himalayan glaciers important and how do they act as water sources?

Himalayan glaciers are vital because they are the primary source of major Asian rivers, including the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus. These glaciers store vast amounts of freshwater and release it slowly throughout the year as meltwater. This ensures a steady supply of water for agriculture, drinking, hydropower generation, and ecosystems across South Asia. As climate change accelerates glacier melting, the long-term water security of millions of people becomes increasingly vulnerable.

3. What is the best time for trekking in the Himalayas?

The most suitable time for trekking in the Himalayas is between April–June and September–November. During these periods, the weather is relatively stable, skies are clear, and visibility is excellent. Monsoon months bring heavy rain, landslides, and slippery trails, while winter brings extreme cold and snow-covered paths. Choosing the right season makes trekking safer and ensures a more enjoyable experience.

4. How is climate change affecting Himalayan ecology?

Climate change is significantly reshaping Himalayan ecology. Glaciers are melting rapidly, altering river flows and increasing the risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). Temperature shifts are forcing plant and animal species to migrate to higher altitudes, while irregular rainfall, droughts, and sudden floods are becoming more common. These ecological disruptions impact agriculture, water supply, biodiversity, and the overall resilience of mountain communities.

5. What environmental issues are caused by human activities in the Himalayas?

Human activities such as unregulated tourism, road construction, deforestation, illegal mining, and unplanned urban expansion are putting immense pressure on the Himalayan ecosystem. These actions lead to soil erosion, habitat loss, increased waste, water pollution, and frequent landslides. Sustainable planning, regulated tourism, and strong environmental policies are needed to mitigate these impacts and preserve the region’s natural balance.

6. How can ordinary citizens contribute to Himalayan conservation?

Citizens can support Himalayan conservation through responsible travel practices, minimizing waste, respecting local customs, and following “Leave No Trace” principles. Supporting local products, reducing plastic use, conserving water, and spreading environmental awareness are effective ways to help. Participating in community-led conservation projects and promoting sustainable tourism also play a crucial role in protecting this fragile mountain ecosystem for future generations.

Sources / References

- Government of India – Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change Reports

- International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) Publications

- National Geographic – Research Articles on the Himalayas and Glaciers

- Geological Survey of India (GSI) – Himalayan Geological Studies

- UNEP & UNESCO – Global Reports on Mountain Ecology and Conservation

- State Forest and Environment Departments of Himalayan Regions