Introduction: The Heart of the Indus Valley Civilization

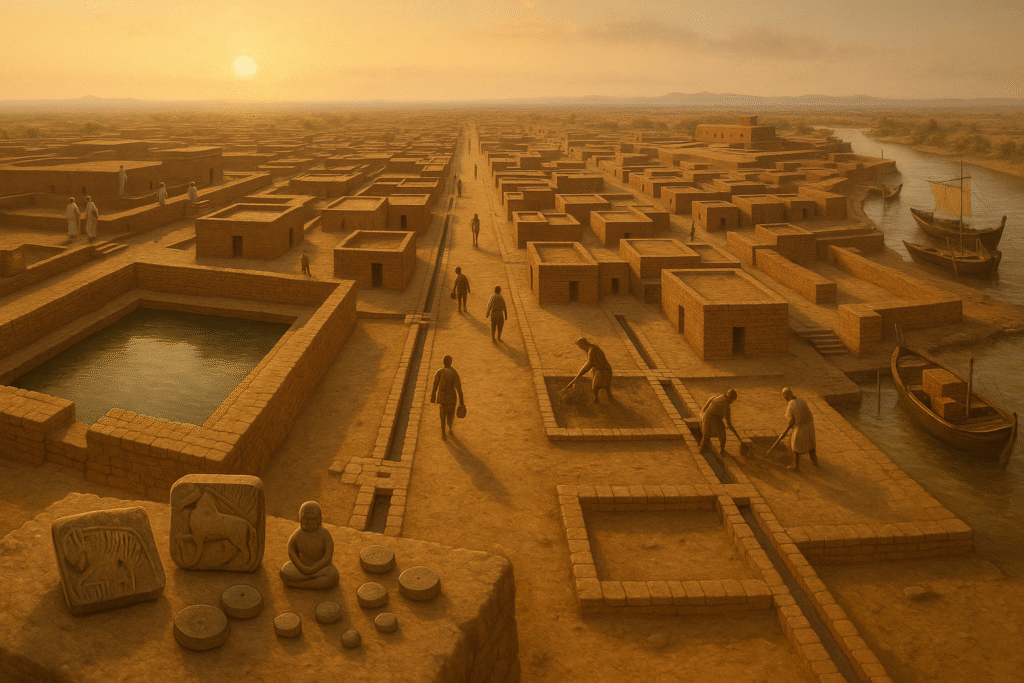

Whenever I explore the history of the Indus Valley Civilization, an extraordinary picture emerges in my mind—a world far older than many great empires, yet far more organized than one would expect from its time. Around 2500 BCE, while most human societies were still scattered in small rural clusters, the people of the Indus Valley were living in well-planned cities, walking through straight grid-pattern streets, using advanced drainage systems, and participating in an orderly economic and social life. What fascinates me most is that their achievements were not simply the result of engineering skill—they reflected a deeper cultural consciousness, discipline, and a sense of community that bound their society together.

As I continued studying this civilization, I came to realize that the Indus Valley is not just a story of bricks, seals, and artifacts—it is a story of human intention. It is the story of how faith, trade, cooperation, and harmony shaped one of the most peaceful and sophisticated societies in ancient history. Their quiet streets, uniform city layouts, and carefully designed public spaces speak to a deeper truth: a civilization flourishes when its people value organization, respect, and collective wellbeing. This is why religion and trade in the Indus Valley appear not as two separate domains, but as interconnected pillars of their social and cultural strength.

📦 Product Title Here

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Rating Here

🔹 Feature or benefit #1

🔹 Feature or benefit #2

The first time I read about the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, the dockyard of Lothal, the beautifully carved seals of Harappa, and the meticulously standardized weights used across hundreds of kilometers, I realized that the Indus people were spiritually and economically advanced in ways that still inspire us today. Their cities share striking architectural similarities, their craftsmanship shows remarkable precision, and their trade networks reflect a strong understanding of value and exchange. Their religious symbols—animal motifs, meditative figures, and ritual objects—suggest that they believed deeply in balance, nature, and inner discipline.

In today’s world, where religious conflict and aggressive commercial competition often divide societies, the Indus Valley Civilization offers a refreshing perspective. Their way of life teaches us that sustainable progress is possible only when spiritual harmony and economic strength grow together. Trade was not merely a pursuit of profit for them—it was a bridge that connected cultures. Religion was not merely ritual—it was a unifying force that guided their moral and communal life.

In this article, I want to take you into that remarkable world—where faith and commerce were companions, where cities were built with vision, and where communities thrived through mutual respect and shared purpose. Let us step into the heart of the Indus Valley Civilization and rediscover the lessons it still holds for us today.

Historical Background: The Rise of the Cities

Understanding the rise of the Indus Valley cities reveals that their development was not accidental. It was the outcome of centuries of learning, adaptation, and collective planning. Around 2600 BCE, many small settlements along the Indus River and its tributaries gradually transformed into major urban centers. This period marks one of the most remarkable transitions in human history—from scattered villages to highly organized, well-planned cities. Among the most prominent of these were Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Lothal, Dholavira, Kalibangan, and Rakhigarhi. What unified these cities was not their size, but their extraordinary level of order, symmetry, and civic consciousness.

One of the most striking features of these cities was their carefully planned layout. Streets were designed in a perfect grid pattern, running north–south and east–west and intersecting at right angles. This arrangement not only made movement easier but also reflected a deep understanding of ventilation, sunlight, and public space management. Unlike many ancient settlements, these cities did not grow chaotically; they were constructed with a vision, as if guided by a silent architectural philosophy rooted in balance and practicality.

Another remarkable aspect was the advanced drainage and sanitation system. Excavations at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa reveal covered drains, underground sewage channels, soak pits, and household waste outlets systematically connected to the main city drainage. Even today, many modern cities struggle to maintain such coordinated infrastructure. The Indus Valley’s emphasis on hygiene and public health shows that the people valued orderliness not just in architecture, but in everyday life as well.

The cities also featured impressive public and administrative structures. Mohenjo-daro’s Great Bath, Dholavira’s massive water reservoir systems, Lothal’s dockyard, and Kalibangan’s fire altars highlight the cultural, religious, and civic priorities of the society. These constructions could only have been possible through efficient leadership, division of labor, and long-term collective planning. Such structures indicate that the civilization was not only technically skilled but also socially coordinated and spiritually inclined.

Trade played a crucial role in the rise and prosperity of these cities. The Indus River and its branches connected settlements to distant regions, enabling both inland and overseas commerce. Cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro became important nodes of a trade network that extended from present-day India and Pakistan to Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. Meanwhile, coastal centers like Lothal served as major maritime hubs. This thriving trade brought wealth, which in turn enabled the growth of sophisticated urban architecture, skilled craftsmanship, and cultural refinement.

Together, these elements show that the rise of the Indus Valley cities was not simply a physical expansion—it was a fusion of social, economic, and cultural evolution. The people of this civilization understood that long-lasting urban development required planning, cooperation, and foresight. Their achievement remains a milestone in world history: a timeless model of sustainable urbanism, civic discipline, and human ingenuity.

Seals, Script, and Trade Identity

Seals and script from the Indus civilization are among its most revealing and mysterious legacies. Small steatite seals, often exquisitely carved with animals, human figures, and geometric motifs, functioned as more than decorative objects—they were tools of administration, commerce, and social identity. Together, these material traces point to a society that valued clear provenance, dependable exchange, and symbolic communication across long distances.

The Function of Seals: Labelling, Ownership, and Proto-Branding (Steatite Seals and Their Marks)

Steatite (soapstone) was widely used for making seals because it was soft enough to carve finely and hard enough after firing to endure repeated use. Seals typically bear combinations of an animal motif—such as unicorn-like figures, bulls, or elephants—alongside short rows of script and abstract signs. In commercial contexts, seals appear to have served as labels and ownership marks, pressed into clay or used to stamp on goods and storage containers to indicate origin, quality, or the responsible workshop or merchant. The recurrence of particular motifs and signs across multiple sites suggests that many seals functioned much like modern trademarks or merchant logos: a compact visual shorthand conveying trust and authenticity.

📦 Product Title Here

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Rating Here

🔹 Feature or benefit #1

🔹 Feature or benefit #2

Archaeologists have also found seals with small perforations or drilled holes, indicating they may have been worn as amulets or carried on strings—further supporting the idea that some seals doubled as personal identifiers. In administrative use, seals likely played a part in record-keeping and the control of goods: a sealed granary or crate would signal tamper-resistance and official sanction. In this way, seals operated across several registers at once—practical security devices, commercial badges, and condensed advertising—helping merchants and producers establish reputations in both local and distant markets.

Script and Its Unsolved Puzzle

The short inscriptions that accompany many seals form the core of the Indus script puzzle. Most texts are extremely brief—often only a handful of signs—making it difficult to discern grammar, syntax, or linguistic structure. Without long continuous texts or a bilingual inscription (the analogue of a Rosetta Stone), attempts to read the script remain provisional. Scholars disagree about its nature: some argue it is logo-syllabic, combining word signs and syllabic markers; others propose links to a pre-Dravidian or other lost language family.

Despite the uncertainty, the script’s repeated association with commercial contexts offers a practical insight: whether or not we can yet read the signs, they clearly functioned as compact conveyors of information—names, quantities, ownership, or commodity types—embedded in the everyday economy. The unsolved status of the script preserves an important lesson: material culture can communicate complex social systems even when the exact words remain beyond our reach.

Religion and Rituals: Public and Private

Religion in the Indus Valley Civilization was woven into both public life and private practice. Archaeological remains—public baths, small shrines, figurines, and ritual objects—suggest a spiritual world that emphasized purity, balance, and communal participation rather than monumental temples or priestly hierarchies seen in some other ancient cultures. In the following sections we explore the best-known evidence: the Great Bath and bathing cult, the diverse corpus of figurines and symbols, and how religious practice intersected with everyday economic life.

Sacred Spaces: The Great Bath and the Ritual of Cleansing

The Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro stands as the most iconic piece of evidence for public ritual in the Indus cities. This large, watertight rectangular tank—carefully constructed with tightly fitted baked bricks, watertight gypsum plaster, and a sophisticated inlet-outlet system—sits within a complex of rooms and stepped galleries, suggesting that it hosted communal gatherings and formal cleansing rites. Its scale and design imply more than simple hygiene: the bath likely served as a focal point for recurring public ceremonies tied to purification, transition, or social cohesion.

📦 Product Title Here

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Rating Here

🔹 Feature or benefit #1

🔹 Feature or benefit #2

Nearby rooms and elevated platforms may have accommodated preparatory activities or observers, indicating a ritual context with social dimensions. Water—managed through reservoirs, wells, and channels across several Indus cities—appears to have held symbolic importance. Although direct textual evidence is absent, the architectural investment in water infrastructure strongly supports the interpretation that collective bathing was imbued with spiritual meaning: a visible practice that reinforced civic identity, moral order, and communal belonging.

Figurines, Totems, and Symbols

The material record of small sculptures, animal motifs, and emblematic seals reveals a rich symbolic universe in which humans and animals appear in intertwined roles. Terracotta and steatite figurines—ranging from stylized mother goddesses to miniature dancers and animals—point to beliefs concerned with fertility, protection, and everyday devotion. Animal figures such as bulls, elephants, and unicorn-like creatures recur on seals and amulets, suggesting clan or guild emblems, protective totems, or markers of sacred stories and cosmologies.

One of the most discussed images is the seated, cross-legged figure found on an inscribed seal, sometimes interpreted as a meditative or proto-yogic posture. While it is tempting to equate this figure directly with later deities, such as the Hindu Śiva, scholarship remains cautious: the seal likely represents a ritual specialist, a mythic ancestor, or a localized spiritual archetype. In any case, the blending of human, animal, and abstract signs—often arranged with geometric precision—indicates a symbolic language that communicated identity, authority, and shared values across workshops and settlements.

The Confluence of Religion and Economic Life

Religious practice and economy in the Indus world appear deeply entangled. Rituals demanded material goods—beads, shell ornaments, special ceramics, and ritual vessels—that sustained artisanal production and trade. Public sites like the Great Bath required maintenance, labor, and resources, creating long-term economic roles for water management specialists, craftsmen, and storekeepers. The built environment of ritual thus simultaneously supported civic religion and local livelihoods.

Moreover, seals and symbolic marks linked spiritual or social legitimacy with commercial exchange. Stamped seals attached to goods acted as assurances of origin, quality, and authorized distribution—functions that carried both economic and moral weight. Festivals, communal rituals, and the social norms encoded in symbolic media likely structured market rhythms and obligations, meaning that religious life helped to stabilize networks of trust essential for both local markets and long-distance trade. The result was a society in which spiritual practice and economic organization reinforced one another, producing civic resilience and cultural continuity.

Case Study: The Journey of a Trade Item — The Carnelian Bead

A single carnelian bead can tell the story of an entire economy. In the Indus world, this small, polished bead was far more than an ornament; it was a node in a network of craft, commerce, and long-distance connection. To follow its journey is to meet the people—stone-picker, bead-maker, merchant, and mariner—whose hands and decisions made ancient trade possible. This case study follows a bead from raw stone to distant market, narrated through the practical steps and human choices that powered the Indus economy.

The story begins at the source: raw carnelian nodules and pebbles collected from riverbeds or semi-precious stone deposits. Skilled workers selected pieces for color and clarity, then rough-shaped them using abrasion and percussion techniques. The semi-finished beads moved to specialized workshops where craftsmen drilled, ground, and polished them. Bead-making furnaces and abrasive pits discovered at excavation sites show that the process was technical and standardized: heat treatment produced deeper reds, and careful polishing created the desirable sheen that made Indus carnelian prized abroad.

Once finished, beads were strung, counted, and bundled. Before leaving the workshop they might receive a seal impression or be packed in containers marked with a merchant’s sign. Here the role of administrative tools becomes visible: seals, standardized weights, and packaging encoded provenance and value. A stamped seal acted like a label of origin and trust; matching weights ensured that exchanges were fair. These systems reduced dispute and allowed merchants to trade with confidence across great distances.

The bead then entered the marketplace. Local dealers bought bundles and consolidated consignments destined for larger hubs. At ports such as Lothal, warehouse clerks, loaders, and sailors coordinated to transfer cargo to ships. The design of these docks—structured berths, storage rooms, and access channels—suggests a sophisticated handling system that protected goods from tidal damage and theft. Onboard, beads traveled in chests alongside copper ingots, shell ornaments, and pottery—each item part of a carefully balanced cargo.

Maritime routes carried the bead to foreign markets: Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, and beyond. There, buyers evaluated color, polish, and any identifying marks. Indus seals found in Mesopotamian contexts indicate reciprocal recognition: foreign merchants could read the visual language of seals even when script remained undeciphered. The bead’s final sale passed value back along the chain—paying miners, craftsmen, and local laborers—while also transmitting styles, motifs, and trust relationships across culture and distance.

This single object’s trajectory reveals how craft specialization, administrative standardization, and maritime logistics worked together in the Indus system. The carnelian bead was not merely a luxury item; it was a compact record of production techniques, economic institutions, and human networks that sustained one of the ancient world’s most remarkable trading civilizations.

Socio-Economic Structure: Satellite Settlements, Artisans, and Merchants

The socio-economic fabric of the Indus Valley was defined by a distributed and interdependent network of urban centres, satellite settlements, skilled workshops, and merchant corridors. Rather than a single, centralized polity, the civilisation appears to have organized production and exchange through a system of core cities—like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro—and numerous smaller satellite towns that supplied raw materials, foodstuffs, and specialised craft inputs. These satellites functioned as logistical nodes: they collected agricultural surplus, processed local resources, and routed goods to urban workshops and markets.

Artisans formed the productive heart of this system. Evidence from excavation zones shows clusters of specialised workshops—bead-makers, metallurgists, potters, and shell-workers—often concentrated in particular neighbourhoods. Skill transmission appears generational and institutionalized: workshop layouts, tool kits, kilns, and waste deposits indicate standardized production techniques and quality control. This specialization allowed craftsmen to refine techniques such as alloying metals, precision bead-drilling, and high-fired ceramics, producing goods with consistent standards suitable for both local consumption and long-distance trade.

Merchants acted as the connective tissue between producers and consumers. They consolidated local outputs, organised storage, and coordinated transport—overland caravans and riverine or maritime routes—to regional hubs and foreign ports. Administrative technologies such as seals, standardized weights, and short inscriptional labels facilitated their work: these devices encoded provenance, quantity, and accountability, reducing transaction costs and enabling trust across distances. Merchant households and agents likely served multiple roles—financiers, logistics managers, and cultural brokers—integrating economic and social networks.

The social arrangement was stratified but functionally interdependent. Farmers, craft specialists, warehouse keepers, water engineers, and port labourers each occupied distinct roles while remaining tied into reciprocal obligations and market exchange. Urban planning—granaries, storage compounds, and dock facilities—reflects coordinated investment in infrastructure that supported this labour ecosystem. Political or religious elites, if present, left little monumental record; instead, authority seems exercised through administrative practices and communal norms embedded in material culture.

In short, the Indus socio-economic model combined decentralised production, concentrated craft expertise, and organized merchant networks to produce resilient urban economies. Its reliance on specialization, logistical coordination, and institutionalized trust offers a durable example of how ancient societies sustained complex commercial life without overtly hierarchical or heavily centralized state apparatuses.

📦 Product Title Here

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Rating Here

🔹 Feature or benefit #1

🔹 Feature or benefit #2

Policy Insights and Modern Lessons: An Inspirational Conclusion

Though the Indus Valley Civilization belongs to a distant past, its principles of urban planning, social harmony, trade ethics, and environmental balance offer powerful lessons for today’s rapidly changing world. Modern societies—shaped by speed, competition, and complex global systems—often search for models that demonstrate how sustainable development and human well-being can coexist. The Indus Valley stands as an inspiring example of how technology, community, and nature can function as integrated pillars of progress.

One of the most compelling lessons is the value of planned urban development. The Indus grid system, advanced drainage structures, and well-designed public spaces prove that cities thrive when built with environmental awareness, public health, and long-term sustainability in mind. Today’s challenges—climate vulnerability, overcrowding, pollution, and infrastructure stress—highlight the need to revisit such ancient models that prioritized balance over expansion.

A second major insight lies in the realm of transparent and reliable trade practices. Standardized weights, seals, and quality-controlled craft industries ensured that commerce in the Indus world was fair, accountable, and trustworthy. These principles remain central to modern global trade, where transparency, accreditation, and standardization underpin economic stability. The Indus example reminds us that trust is not a cultural luxury but an economic necessity.

A third lesson comes from the civilization’s approach to religion and social cohesion. In the Indus cities, religious practice appears to have united communities rather than divided them. Rituals and symbols provided moral grounding, fostered shared identity, and contributed to social order. In a world where identity-based tensions can escalate quickly, the Indus model shows how spiritual frameworks can support harmony, not conflict.

In the end, the Indus Valley teaches us that progress flourishes through balance—a harmony between technology, social ethics, and ecological sensitivity. These lessons are relevant not only for policymakers and urban planners but for businesses, educators, and everyday citizens. The civilization’s legacy is more than archaeological wonder; it is a timeless reminder that sustainable futures are built on cooperation, respect for nature, and a commitment to shared prosperity.

FAQs: Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why has the Indus script not been deciphered yet?

Most inscriptions of the Indus script are extremely short, usually containing only a few signs. Without longer texts or a bilingual inscription (like the Rosetta Stone), linguists cannot establish grammar or meaning. Many attempts have been made, but no universally accepted decipherment exists yet.

2. Did the Indus Valley Civilization have temples or formal religious buildings?

No large temples have been identified so far. However, structures like the Great Bath, fire altars at Kalibangan, small shrines, and numerous figurines suggest that religious practice existed both at the community and household level. Their religion appears symbolic, ritualistic, and integrated into daily life rather than centered on monumental temples.

3. Why is the port of Lothal considered so important?

Lothal contains one of the world’s earliest known dockyards. Its sophisticated design shows the Indus people's advanced knowledge of maritime engineering. Artifacts found there indicate active trade with Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, and Oman, proving that the Indus Civilization had a strong international trade network.

4. What were seals used for in the Indus Civilization?

Seals served as labels, ownership marks, and authentication tools. Merchants used them to stamp goods, identify producers, and ensure quality. The symbols and animals carved on these seals functioned like early trademarks, helping regulate trade and maintain trust across long distances.

5. What were the major trade goods of the Indus Valley?

Carnelian beads, shell ornaments, copper-bronze tools, pottery, textiles, and steatite seals were among the most traded items. These goods were exchanged both locally and with distant regions such as Mesopotamia, reflecting the civilization’s strong craft traditions and commercial reach.

6. Was the Indus Valley Civilization warlike?

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Indus people were largely peaceful. Few weapons have been found, and there is no indication of large-scale warfare or military structures. Their society seems to have thrived on cooperation, urban planning, and trade rather than conflict.

7. What caused the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization?

Scholars believe multiple factors contributed: shifting river patterns, climate change, declining agricultural productivity, and disruptions in long-distance trade routes. The decline appears gradual rather than sudden, indicating a slow transformation rather than a catastrophic collapse.

8. Does the Indus Valley Civilization influence modern South Asian culture?

Yes, traces of Indus influence appear in craft traditions, urban planning ideas, water-management techniques, symbols, jewelry styles, and elements of social organization. While direct continuity cannot always be proven, many cultural echoes remain visible today.

References / Read More

To understand the Indus Valley Civilization in depth, scholars rely on a combination of archaeological reports, excavation records, material analyses, and comparative studies. These sources shed light on the civilization’s urban planning, trade networks, religious symbols, craftsmanship, and social structures. From the great cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro to the port town of Lothal and the water-management marvels of Dholavira, each site adds a new dimension to our knowledge.

For readers who wish to explore further, the following sources are highly recommended:

- Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) — Excavation reports, artifact catalogues, and official documentation on major Indus sites.

- Harappa Archives — High-quality images and detailed research notes on seals, weights, crafts, and city layouts.

- International Indus Research Journals — Contemporary research on script studies, trade routes, maritime links, and symbolic systems.

- Key Books — “The Indus Civilization” by Mortimer Wheeler, “Understanding Harappa,” and “The Indus–Saraswati Civilization.”

These resources offer deeper insights into archaeological discoveries and help readers appreciate how the Indus Valley shaped early urban life, long-distance trade, and cultural development across the ancient world.