Historical and Cultural Perspective

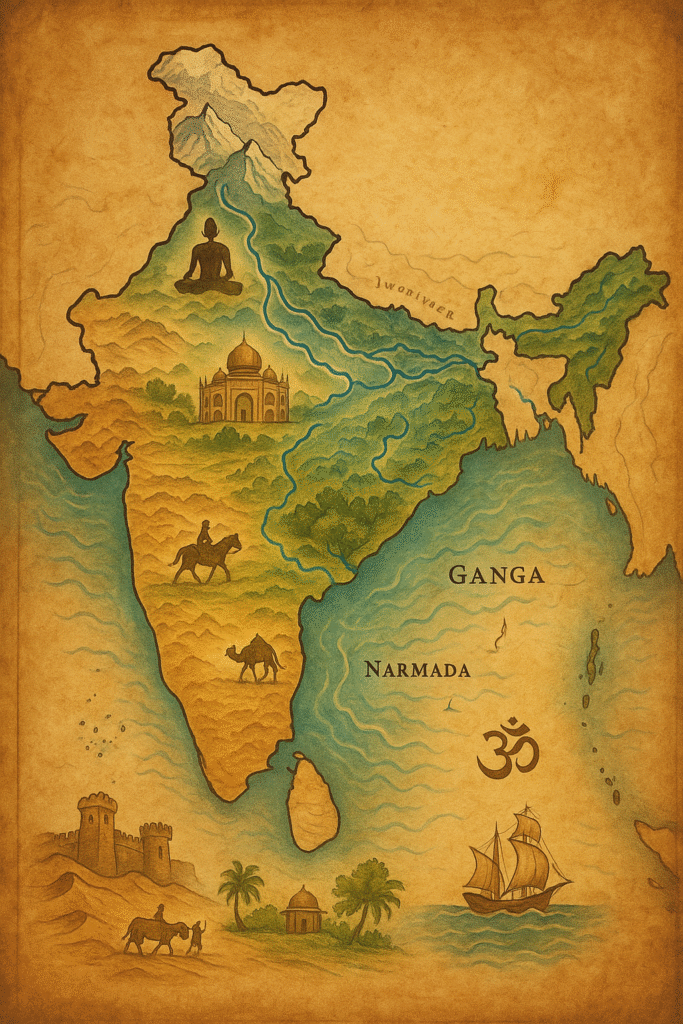

The geography of India has never been a passive background; it has been an active architect of its history, economy, and culture. From the fertile plains of the Indus Valley Civilization to the trade-rich coastal kingdoms and the modern nation-state, India’s terrain has continuously shaped patterns of settlement, governance, and belief. Rivers nurtured agriculture and urban growth, mountains offered security and isolation, while coastlines opened doors to maritime trade and cultural exchange. Geography thus became the silent yet most influential force in India's civilizational evolution.

Religion and cultural practices have been deeply intertwined with geographical features. The Ganga, Yamuna, and Narmada rivers are not merely water bodies — they are sacred entities that sustain faith as much as they sustain life. Rituals like holy bathing, pilgrimages, and seasonal festivals arose from the cycles of nature governed by these rivers. The Himalayas, with their snow-clad peaks, became symbols of divinity and endurance, inspiring spiritual reflection and mythological reverence. Similarly, the coastal regions nurtured maritime communities whose festivals, occupations, and folklore echoed the rhythm of the sea.

Geography also determined political boundaries and the nature of governance. Mountain ranges such as the Himalayas and the Aravallis acted as natural fortresses, protecting territories from invasions while fostering unique regional cultures. In contrast, fertile river valleys — like those of the Ganga and Godavari — supported dense populations, giving rise to centralized kingdoms and complex administrative systems. Coastal access transformed regions like Gujarat, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu into trade hubs that linked India to Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Through these exchanges, India absorbed new languages, foods, and ideas while also exporting its spices, textiles, and philosophies.

The diversity of India’s geography led to cultural diversity. People living in the Himalayan foothills developed distinct agricultural and dietary practices compared to those on the plains. In the fertile Gangetic region, surplus crops allowed the growth of cities, crafts, and organized governance. In the south, the monsoon-fed coastal belt produced spices, coconuts, and maritime industries, making it a global center for trade and cultural dialogue. Every terrain encouraged adaptation — shaping dialects, art forms, and local customs that still endure.

Geography also influenced conflict, strategy, and trade. The mountain passes of the northwest, such as the Khyber and Bolan, were conduits for both invasion and exchange. Empires rose and fell along these routes, each integrating local topography into their defense and expansion strategies. Forts were constructed on high ridges, cities emerged along navigable rivers, and trade caravans followed predictable paths shaped by geography. Coastal fortifications and ports like Lothal, Calicut, and Bombay stand today as reminders of how terrain dictated both vulnerability and opportunity.

Over centuries, the geographical mosaic of India cultivated resilience and pluralism in its people. Living amidst varied climates, resources, and ecological conditions taught communities how to coexist with difference. The coexistence of deserts and rainforests, glaciers and deltas, created not separation but synergy — a natural pluralism reflected in India’s languages, cuisines, music, and philosophies. Geography thus became both a challenge and a teacher, compelling adaptation and cooperation.

In conclusion, India’s historical and cultural evolution cannot be understood without understanding its geography. The rivers shaped livelihoods and faith, the mountains shaped defense and spirituality, and the coasts shaped exchange and innovation. Geography has been the silent scriptwriter behind India’s civilizational story — guiding where people lived, how they worshipped, what they traded, and how they connected with the world. In the following section, we will explore the core geographical features — the Himalayas, rivers, and coastlines — and analyze their continuing economic and strategic importance in modern India.

Geographical Features: The Himalayas, Rivers, Coastlines, and Plateaus

The geography of India is remarkable for its diversity and vastness. From the snow-clad peaks of the Himalayas in the north to the rolling coastlines of the south, from the fertile river plains to the rugged central plateaus, every region contributes uniquely to the country’s natural and cultural identity. These geographical features have not only defined India’s climate and ecosystems but have also influenced its agriculture, economy, trade, and strategic outlook. Together, they form the living foundation of the Indian subcontinent’s civilization.

The Himalayas: The Northern Shield

Stretching over 2,400 kilometers across the northern frontier, the Himalayas form a towering wall that separates the Indian subcontinent from Central Asia. These mountains, among the youngest and highest in the world, are both a symbol of strength and a source of life. The Himalayas give birth to the great perennial rivers — the Ganga, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, and Indus — that nurture millions of lives downstream. Beyond their scenic grandeur, they regulate India’s weather patterns by blocking cold winds from Central Asia and trapping the monsoon rains within the subcontinent.

Ecologically, the Himalayas are a biodiversity hotspot, home to rare flora and fauna and countless medicinal plants. Strategically, they serve as a natural defense barrier, historically protecting India from invasions. Yet, they are also fragile ecosystems vulnerable to climate change, deforestation, and glacial retreat. Sustainable tourism, afforestation, and transboundary water cooperation with neighboring countries are essential for preserving this crucial mountain system that sustains both India’s ecology and economy.

The Rivers: Lifelines of Civilization

The rivers of India have shaped both its geography and civilization. The northern rivers — Ganga, Yamuna, Ghaghara, and others — originate in the glaciers of the Himalayas and flow perennially, nourishing the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains. In contrast, the southern rivers like Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, and Narmada arise from the peninsular plateau and depend on monsoon rains. These rivers sustain agriculture, industry, and domestic life while also carrying deep cultural and spiritual meaning.

The Ganga, often called the “Mother River,” has been at the heart of India’s religious and social consciousness for millennia. The river valleys have been cradles of civilization, supporting dense populations and urban growth. However, increasing pollution, over-extraction, and mismanagement now threaten their sustainability. Reviving traditional water management systems such as stepwells, tanks, and rainwater harvesting — combined with modern technology — is essential to ensure long-term water security. Rivers are not merely physical entities but dynamic ecosystems that must be respected and restored.

The Coastline and Maritime Significance

India’s coastline stretches for about 7,500 kilometers, touching the Arabian Sea in the west and the Bay of Bengal in the east. These coastal regions are vital hubs of trade, industry, fisheries, and tourism. Major ports such as Mumbai, Kochi, Chennai, and Visakhapatnam are gateways to global commerce and engines of economic growth. The coastal plains are also rich in biodiversity — mangroves, coral reefs, and wetlands that buffer the land against cyclones and erosion.

From a strategic perspective, India’s maritime geography gives it a commanding position in the Indian Ocean. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands, situated near key sea lanes, are crucial for maritime security and trade surveillance. The concept of the “Blue Economy” — sustainable use of ocean resources — is increasingly shaping India’s coastal policies. Yet, these regions face growing threats: sea-level rise, coastal erosion, pollution, and unsustainable development. Protecting marine ecosystems while empowering coastal communities with modern livelihood opportunities is essential for maintaining balance between growth and conservation.

The Plateaus and Plains: The Core of India

The Deccan Plateau, covering most of southern and central India, forms the ancient geological heart of the subcontinent. It is a vast region of volcanic origin, rich in minerals such as coal, iron ore, bauxite, and manganese. This wealth has made the plateau an industrial powerhouse. Cities like Nagpur, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru have grown into centers of technology, trade, and innovation — illustrating how geography supports economic transformation.

The northern plains, formed by the alluvial deposits of the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers, are among the most fertile agricultural regions in the world. Here, crops like rice, wheat, and sugarcane are cultivated in abundance, sustaining millions of farmers. In contrast, the western Thar Desert presents a stark yet vital landscape — traditionally dependent on animal husbandry and now emerging as a hub for renewable energy projects, particularly solar and wind power. This shows how even arid geographies can be harnessed sustainably through innovation and planning.

The plateau and plains together represent the dynamic interplay between natural endowment and human effort. The fertile valleys have given rise to dense civilizations, while the rocky plateaus have fostered resilience and enterprise. As India urbanizes and industrializes, maintaining ecological equilibrium in these regions is crucial to ensure that growth does not come at the cost of sustainability.

In essence, India’s geographical diversity is not just a matter of physical variation — it is the living framework upon which its economy, culture, and civilization have evolved. From the Himalayas to the coasts, and from rivers to deserts, each region contributes uniquely to the identity of the nation. This interlinked web of ecosystems, economies, and cultures makes India a microcosm of the world — where every terrain, every climate, and every resource exists in harmony. In the next section, we will explore how this geographical richness influences India’s climate, biodiversity, and environmental policies — shaping the challenges and opportunities of the future.

The Himalayas: Source, Shield, and Sensitive Ecosystem

The Himalayas are more than a mountain range; they are the living backbone of northern India. Stretching across the subcontinent’s northern frontier, these peaks feed the great perennial rivers — the Ganga, Yamuna, and Brahmaputra — and thus underpin the water security of hundreds of millions. They influence climate by blocking cold continental winds and shaping monsoon patterns that sustain agriculture across vast plains. Ecologically, the Himalayas host unique biodiversity and countless medicinal plants, while their forests stabilize slopes and regulate downstream sediment flows.

Strategically, the mountain chain has historically acted as a natural bulwark, defining borders and shaping defense thinking. Economically and culturally, Himalayan valleys support pastoral communities, terrace agriculture, and pilgrimage circuits that sustain local livelihoods. Yet the range is fragile: accelerating glacier retreat, increased landslides, deforestation, and unplanned tourism threaten its resilience. Addressing these pressures requires integrated approaches — transboundary river cooperation, community-led afforestation, sustainable tourism practices, and investments in early-warning and slope-stabilization technologies — so that the Himalayas continue to serve as source, shield, and sanctuary for generations to come.

Rivers and Water Management: Lifelines and Governance Challenges

Rivers are the circulatory system of India’s economy and culture. The perennial northern rivers nourished ancient civilizations and today support intensive agriculture, industry, and urban centres. Peninsular rivers, by contrast, are more seasonal and closely tied to monsoon rhythms. Across regions, rivers provide irrigation, drinking water, hydropower, and cultural identity — but their utility is under threat from pollution, over-extraction, poorly planned river engineering, and changing rainfall patterns.

Effective water management must blend traditional practices with modern science. Revival of tanks, stepwells and community ponds, coupled with watershed management, groundwater recharge, rainwater harvesting, and demand-side efficiency in irrigation, can restore hydrological balance. Institutional reforms are equally important: basin-scale planning, inter-state cooperation, transparent data sharing, and incentives for water-efficient crops and technologies. Importantly, rivers are living ecosystems; policies must prioritize ecological flows, pollution control, and riverfront conservation to secure long-term water security for both people and nature.

Coastline and Maritime Strategy: Economic Opportunity and Strategic Imperative

India’s long coastline and island territories give it critical maritime advantage in the Indian Ocean. Coastal ports are nodes of trade and industry, fisheries sustain millions of livelihoods, and marine ecosystems like mangroves and reefs provide natural storm protection and carbon sinks. Strategically, control of sea lanes and maritime awareness are central to national security and regional influence.

Balancing growth and conservation is key: sustainable port development, pollution control, community-based fisheries management, and coastal habitat restoration are essential. Strengthening maritime surveillance, investing in resilient coastal infrastructure, and integrating coastal communities into planning ensure that the coastline remains both an engine of prosperity and a line of defence.

Climate and Biodiversity

India’s climate and biodiversity are two of its most defining and interdependent attributes. Spanning tropical, subtropical, temperate, and alpine zones within a single peninsula, India hosts a remarkable range of climatic regimes and ecosystems. The interaction between the monsoon system, the Himalayan rain shadow, coastal moisture, and varied topography has created microclimates that sustain unique flora and fauna across forests, wetlands, mangroves, coral reefs, grasslands, and alpine meadows. This ecological variety makes India a global biodiversity hotspot and underpins the livelihoods of millions.

The monsoon is central to India’s climate story. Seasonal reversal of winds brings concentrated rainfall that supports rain-fed agriculture and replenishes groundwater. Regions such as the Western Ghats and the northeastern Himalaya receive heavy precipitation and sustain dense evergreen forests, while the rain-shadow zones and the Thar Desert receive sparse rainfall and support drought-adapted ecosystems. These climatic contrasts have given rise to region-specific crops, traditional knowledge systems, and community practices for water and land management.

Biodiversity provides essential ecosystem services — pollination, soil formation, water purification, carbon sequestration, and coastal protection. Mangrove belts buffer storm surges and reduce erosion; wetlands filter pollutants and store floodwaters; forests regulate local climates and sustain freshwater flows. Economically, biodiversity supports fisheries, forestry, agriculture, and ecotourism, contributing directly to rural incomes and national GDP. Culturally, many species and landscapes are woven into local rituals, medicinal systems, and identities, reinforcing conservation values across communities.

Yet India’s climate and biodiversity face mounting threats. Rising temperatures, altered monsoon patterns, accelerated glacial melt, and increasing frequency of extreme events such as heatwaves, droughts and cyclones are changing habitat conditions. Habitat fragmentation, pollution, invasive species, overexploitation of resources, and land-use change further erode ecological resilience. Coral bleaching, mangrove loss, and declining population trends in many endemic species are early warning signals that conservation is urgent and non-negotiable.

Addressing these challenges requires integrated, multi-scalar approaches. Nature-based solutions — ecosystem restoration, mangrove reforestation, wetland conservation, and landscape connectivity — provide cost-effective ways to enhance resilience while delivering multiple benefits. Climate adaptation must be married to biodiversity protection through measures such as community-led watershed management, agroecological practices that boost soil health and biodiversity on farms, and protected-area networks that maintain ecological corridors for species movement.

Policy and governance are equally important. Strengthening legal protections, expanding and effectively managing protected areas, mainstreaming biodiversity considerations into development planning, and incentivizing sustainable livelihoods can all reduce pressure on ecosystems. Scientific monitoring, citizen science, and open data systems help track ecological change and guide adaptive management. Crucially, meaningful participation of local communities and indigenous knowledge systems must be central to conservation strategies, since these actors often hold practical knowledge about sustainable resource use.

In conclusion, India’s climate and biodiversity are inseparable pillars of its sustainability agenda: protecting one reinforces the other. Ensuring resilient ecosystems will require coordinated action across sectors, scales, and societies — combining traditional wisdom, modern science, and inclusive policy — so that India’s rich natural heritage continues to sustain both nature and people into the future.

Economic and Strategic Importance: Resources, Transportation, and Maritime Routes

India’s geography is not just a matter of natural beauty; it is the foundation of its economic development and strategic influence. The nation’s vast and varied landforms, abundant natural resources, extensive river systems, and long coastline have endowed it with a unique geopolitical position — one that connects South Asia with the broader Indo-Pacific region. This section explores how India’s geography contributes to its economic strength and strategic relevance through its resources, transportation networks, and maritime connectivity.

Natural Resources and Economic Growth

India’s land is a treasure trove of natural resources that sustain its diverse economy. The fertile plains of the north, enriched by the alluvial deposits of the Ganga and Brahmaputra, support intensive agriculture producing rice, wheat, sugarcane, and pulses. These regions form the backbone of India’s food security. In contrast, the peninsular plateau is rich in mineral wealth — including coal, iron ore, bauxite, manganese, copper, and mica — which power the country’s industrial base. States like Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Karnataka have emerged as key centers of mining and heavy industry.

India’s western arid regions, particularly Rajasthan and Gujarat, are emerging as renewable energy hubs due to abundant solar and wind potential. Meanwhile, the coastal belts of the south and west sustain thriving fisheries, aquaculture, and offshore mineral extraction. This geographical diversity allows India to build a balanced and resilient economy — where agriculture, industry, and services complement each other across regions. It also underlines India’s self-reliant model of growth, where different ecosystems contribute uniquely to national prosperity.

Transportation Networks and Spatial Connectivity

India’s geography has played a pivotal role in shaping its vast transportation network. The north-south and east-west corridors integrate remote regions with national markets, facilitating both trade and mobility. Rivers like the Ganga and Brahmaputra serve as inland waterways, providing cost-effective transport for goods and people. Meanwhile, mountain passes such as Nathu La and Lipulekh in the Himalayas act as strategic gateways for cross-border trade with China, Nepal, and Bhutan.

The railways and highways form the arteries of India’s internal economy. The Indo-Gangetic plains, with their gentle terrain, host dense rail and road networks that connect industrial hubs with ports and markets. Initiatives such as the Bharatmala (road development) and Sagarmala (port-led development) projects aim to enhance logistics efficiency, reduce travel time, and boost trade competitiveness. These projects are not merely infrastructural upgrades — they are instruments of regional integration, economic inclusivity, and national security.

Air connectivity has further transformed India’s geography into an integrated economic space. Major international airports in Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, and Bengaluru link India with global supply chains, tourism, and investment networks. Together, these multimodal systems exemplify how geography can be harnessed through infrastructure to drive sustainable economic transformation.

Maritime Routes and Strategic Position

With a coastline of over 7,500 kilometers and its central location in the Indian Ocean, India enjoys one of the world’s most strategic maritime positions. The country sits astride major sea lanes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia — routes that carry a significant portion of global energy and trade. Critical chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca, and the Gulf of Aden define India’s maritime neighborhood, giving it both opportunities and responsibilities in ensuring regional stability.

This geographical advantage underpins India’s evolving role as a “net security provider” in the Indo-Pacific. The Indian Navy plays a key role in maritime security, anti-piracy operations, and humanitarian missions. Island territories such as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Lakshadweep archipelago serve as forward bases for surveillance and strategic outreach, enhancing India’s capacity to monitor critical sea lanes and respond to emergencies.

Economically, India’s maritime geography supports the “Blue Economy” — the sustainable use of ocean resources for growth, jobs, and ecosystem health. Fisheries, offshore minerals, port-based industries, and coastal tourism are vital components of this framework. Policies that empower coastal communities, modernize ports, and promote renewable ocean energy are essential for ensuring that growth does not compromise ecological balance. In this way, India’s coastal geography acts as both an economic lifeline and a strategic shield.

Strategic Outlook and Future Direction

India’s geography gives it a natural advantage in shaping regional and global geopolitics. Through policies such as the “Act East Policy,” “Neighborhood First,” and “SAGAR” (Security and Growth for All in the Region), India seeks to leverage its location to foster connectivity, trade, and stability across Asia and the Indian Ocean. Land-based transport corridors, such as the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), and maritime initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative, further integrate India with global trade and supply networks.

In essence, the economic and strategic importance of India’s geography lies in its balance of land-based resources and oceanic power. Its fertile plains feed the population, its plateaus fuel industries, and its coasts connect it to the world. The same geographical diversity that nurtures India’s civilization also demands responsible stewardship. By investing in sustainable resource management, resilient infrastructure, and maritime strength, India can continue to convert its geographical advantage into long-term prosperity and security — ensuring that geography remains its greatest asset in the 21st century.

Geographical Challenges and Solutions: Floods, Droughts, and Land Degradation

India’s geographical diversity, while a great strength, also presents a complex set of environmental challenges. Among the most persistent are floods, droughts, and land degradation — phenomena that affect millions of people every year. These challenges are not isolated; they are deeply interconnected, driven by both natural factors and human actions. Addressing them requires a balanced combination of scientific planning, traditional wisdom, and community participation.

Floods: The Dual Face of Water Abundance

Floods in India are largely a result of monsoonal irregularities, river overflow, and human interference with natural drainage systems. The Ganga, Brahmaputra, and their tributaries frequently overflow during heavy rainfall, inundating large parts of Bihar, Assam, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. Floods destroy crops, displace populations, and damage infrastructure, turning natural abundance into economic disaster.

Human-induced factors have intensified this problem — rampant encroachment on floodplains, deforestation in catchment areas, and unplanned urban expansion block natural drainage paths. The solutions lie in adopting a multi-dimensional approach: scientific river management, restoration of wetlands, and construction of flood-resilient infrastructure. Early warning systems, community training programs, and climate-resilient urban planning are equally essential. River rejuvenation projects like the “Namami Gange Mission” should integrate floodplain management and ecological restoration, not just pollution control.

Drought: Water Scarcity and Mismanagement

Drought is the other extreme of India’s climatic imbalance, particularly affecting arid and semi-arid regions such as Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and parts of Tamil Nadu. While erratic rainfall is a natural cause, human factors such as overexploitation of groundwater, deforestation, and inefficient irrigation practices exacerbate the crisis. Drought affects agriculture, drinking water availability, and livestock, creating cycles of poverty and migration.

The revival of traditional water harvesting systems — johads, stepwells, tanks, and ponds — offers a sustainable solution. Integrating these traditional methods with modern technologies like drip irrigation, micro-sprinklers, and rainwater harvesting can significantly reduce vulnerability. The promotion of drought-resistant crops like millets and pulses, coupled with community-level watershed management, enhances resilience. On a policy level, the creation of decentralized water governance systems and mandatory rainwater harvesting in urban areas can ensure long-term sustainability.

Addressing drought also demands climate adaptation strategies — reforestation, soil moisture conservation, and efficient groundwater recharge programs. Drought is not merely a natural disaster; it reflects how wisely we manage our available water resources.

Land Degradation: Erosion of Productivity and Ecology

Land degradation is one of India’s most pressing yet often overlooked environmental issues. Excessive deforestation, overgrazing, mining, and unplanned agriculture have led to soil erosion and declining fertility. According to reports, nearly 30% of India’s land area is affected by some form of degradation. The loss of fertile topsoil not only reduces crop productivity but also disrupts ecological stability.

Sustainable land management practices can reverse this trend. Techniques such as contour plowing, agroforestry, and terracing help reduce erosion and restore soil health. Large-scale afforestation using native species, soil conservation programs, and the enforcement of environmental regulations for mining and construction are essential. Integrating “Environmental Impact Assessments” (EIA) into every major land-use project can help prevent further degradation.

In conclusion, India’s geographical challenges — floods, droughts, and land degradation — are the result of the delicate balance between nature and human intervention. While the scale of these problems is vast, the solutions are within reach. By combining modern science with indigenous knowledge, promoting participatory governance, and emphasizing sustainable resource use, India can transform these challenges into opportunities. Protecting land and water is not just an environmental obligation — it is vital for economic security, food safety, and the long-term survival of humanity.

My Story / Personal Experience and Learnings

I grew up in a small village in Rajasthan, where geography was not just a subject — it was a lived reality. Every season had its own rhythm, every gust of wind carried a message, and every crack in the parched earth told a story of resilience. Summers were harsh, often crossing 45°C, and the wells would dry up by June. As children, we would take turns drawing water from the community well, sometimes spending hours to fill just a few buckets. It was then that I first realized geography is not merely about maps and mountains; it is about how the earth shapes our habits, struggles, and survival.

In our village, rainfall was scarce, and every drop of water was precious. My grandfather had an old stone tank that he would clean every summer in preparation for the monsoon. When the first drops of rain fell and water began to fill that tank, it felt as if life had returned to the land. My grandfather often said, “He who understands the earth never loses.” That simple sentence became a guiding truth for me. I learned that harmony with nature was not a choice — it was a necessity.

When I went to college and chose geography as my major, it wasn’t just an academic decision — it was an extension of my childhood experiences. As I studied the Himalayas, monsoons, and coastal systems, I began to see a larger pattern — how my village’s droughts were part of the same environmental story as floods in Assam or land degradation in Madhya Pradesh. Geography, I realized, was the invisible thread connecting every human life to the planet. Solutions to our crises could not come from policies alone; they needed awareness, adaptation, and respect for local wisdom.

After graduation, I joined a water conservation project in a drought-prone district. During a field visit, I found a village that had been struggling with water scarcity for years. Despite government aid, their wells remained dry. On speaking with the elders, I discovered that several traditional ponds had fallen into disuse — clogged with weeds and debris. We began a community campaign to revive those ponds. It took weeks of effort, but when the monsoon arrived and water began to fill those ancient tanks, the joy in the villagers’ eyes was indescribable. That day, I realized that true development is not imposed from above — it begins with people reclaiming their connection to nature.

Through that experience, I learned that collective participation is the foundation of sustainable change. Geography teaches us that the earth responds when we listen to it. Nature does not deny resources; it simply demands responsibility. Working in that project taught me that sustainable development is not a theoretical concept — it is a lived philosophy where traditional knowledge meets modern innovation.

Later, I participated in several other environmental projects, including soil conservation and afforestation drives. Once, during a tree-planting campaign with schoolchildren, a young boy asked me, “Sir, will these trees bring us more rain?” His innocent question struck me deeply. It reminded me that behind every scientific effort lies a human hope — that our actions, however small, can heal the planet. The boy’s words reinforced my belief that environmental responsibility is not about laws or lectures — it’s about nurturing faith in future generations.

Today, when I look back, I realize that my life itself has been a geography lesson — one that taught me patience, observation, and empathy. From the silence of the desert to the first drops of rain on dry soil, every moment carried wisdom. The mountains, rivers, plateaus, and coastlines are not just features of the earth — they are reflections of human endurance, creativity, and coexistence.

My greatest learning is that geography is not merely to be studied; it must be lived. When we understand the language of the land, respect the flow of water, and nurture the forests that protect us, we align ourselves with the planet’s natural harmony. Sustainable progress will only be possible when we learn to see the earth not as a resource to be used, but as a living system to be cared for. Geography, in the truest sense, is the art of living wisely on this shared planet.

Problem / Example of Difficulty

A few years ago, I was working on a water conservation project in a drought-prone village in Rajasthan. The community had been facing severe water scarcity for several consecutive years. The villagers depended almost entirely on agriculture, but declining rainfall and excessive groundwater extraction had worsened the situation. Wells and hand pumps had dried up, fields were cracked, and fodder for cattle had become scarce. Women and children had to walk several kilometers daily to fetch water, often spending half the day in this task — leaving little time for education or livelihood activities.

When I conducted an initial survey of the area, I realized that the crisis was not just about a “lack of water” — it was about a “lack of management.” The traditional ponds and water tanks that once stored rainwater had been neglected for decades. The land still had the capacity to hold water if these systems were revived. However, people had lost faith in the possibility of change. Government schemes existed only on paper, and the local community, disheartened by repeated failures, had stopped participating in collective action.

It was then I understood that the biggest challenge is not always natural — it is psychological and social. When a community loses hope, even the simplest solutions seem impossible.

Solution and Lessons

In that drought-affected village, we began our work with a simple idea — community participation. The first step was to gather the villagers in the central courtyard and talk about the possibility of bringing water back. At first, many were skeptical, but a few elders and young volunteers came forward. Together, we started cleaning the old ponds and tanks that had been abandoned for years. Each household contributed — some provided labor, others tools, and a few helped with funds or food for the workers. Slowly, the entire village united around a common goal.

After months of effort, the monsoon arrived, and for the first time in decades, those ancient ponds began to fill again. The sight of water shimmering in the sun brought tears of joy to many eyes. Livestock had water to drink, the fields turned green once more, and women no longer had to walk miles to fetch water. What began as a small initiative became a symbol of hope and self-reliance for the entire community.

The greatest lesson I learned was that no challenge is insurmountable when people come together with trust and determination. Real change is born not from money or machinery, but from collective will and respect for nature. Geography, at its heart, teaches us this — the Earth gives back exactly what we give to her.

Future Framework: Policy Recommendations and Citizen Role

The geographical significance of India is not confined to its past or present — it is the key to shaping its future. In the coming decades, as challenges like climate change, population growth, and rapid urbanization intensify, geography-based policymaking will become essential for sustainable development. The time has come to recognize that the Earth's resources are finite, and only their judicious use can ensure long-term human well-being.

At the policy level, there is a strong need for an integrated geo-management framework — one that views land, water, forests, and biodiversity as interconnected systems. Policies must be region-specific rather than based on national averages. For example, the Himalayan region requires a dedicated mountain policy focusing on slope stability, forest conservation, and eco-tourism; coastal states need a maritime strategy emphasizing “Blue Economy” growth with ecosystem protection; and arid regions should prioritize water harvesting and renewable energy.

Technology and data-driven planning will play a crucial role in the future. Tools like satellite monitoring, GIS mapping, and climate modeling can help governments accurately assess the availability and vulnerability of natural resources. At the same time, environmental impact assessments (EIA) must be mandatory for all major projects — from mining to infrastructure — to ensure that economic growth aligns with ecological balance.

However, citizens’ participation is equally vital. Every individual must assume responsibility for their local environment — through water conservation, tree planting, waste management, and energy efficiency. Small, consistent actions at the community level can collectively lead to large-scale change. Environmental education in schools and colleges should go beyond textbooks and include real-world engagement to create environmentally conscious citizens.

Ultimately, safeguarding India’s geography and environment requires more than government policies — it needs informed citizens and scientific awareness. If we learn to understand and respect our natural heritage, we can build a future that is not only economically prosperous but also ecologically resilient, ensuring a balanced and secure planet for generations to come.

Conclusion

India’s geography is not merely a physical description of its land — it is the very essence of its civilization. From the towering Himalayas to the vast coastlines, from fertile plains to arid deserts, each landscape contributes uniquely to the nation’s security, economy, and culture. Understanding and respecting this geographical diversity is essential for building a sustainable and prosperous future. The more we align our development with nature’s rhythm, the more resilient and balanced our progress will be.

Today, every citizen, policymaker, and student has a role to play — whether it’s conserving water, planting trees, or protecting local ecosystems. Geography teaches us that growth and preservation are not opposites but partners in progress. The responsibility to protect our planet begins with small, consistent actions taken together.

References

- Survey of India: https://www.surveyofindia.gov.in/ — Official maps, topographical data, and boundary-related information about India’s geography.

- India Meteorological Department (IMD): https://mausam.imd.gov.in/ — Authentic data on monsoon, temperature variations, and climatic patterns across India.

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC): https://moef.gov.in/ — Government reports and policies related to environment, biodiversity, and climate conservation.

- Geological Survey of India (GSI): https://www.gsi.gov.in/ — Official data on India’s geological structure, mineral resources, and land formations.

- NITI Aayog: https://www.niti.gov.in/ — Reports on sustainable development, water resource management, and geographical planning in India.

- World Bank and UNDP Reports: — Provide global insights into sustainable development, climate resilience, and resource management.

- Academic Sources: NCERT and ICSE geography textbooks, along with journals such as “Economic and Political Weekly,” offer valuable academic perspectives on India’s geography and environment.

Note: All the above sources are publicly available and recognized for educational, research, and policy purposes. They should be used responsibly for academic and informative objectives only.