Introduction: Understanding the Spirit of 1909

My journey into the history of the Indian Councils Act 1909 (also known as the Morley–Minto Reforms) began with a single date and a footnote in an old book. What seemed like just another chapter in colonial administration soon revealed itself as a turning point — a political moment that reshaped representation, identity, and the future course of India’s freedom movement.

A Personal Lens: How This Story Began

As I flipped through archival documents, debates, and historical commentaries, I realized that the reforms of 1909 were not just administrative adjustments. They reflected the fears, strategies, and negotiations between a rising Indian political consciousness and a colonial government trying to retain control. This personal exploration helped me see how decisions made over a century ago continue to echo in our political landscape today.

What Was the Indian Councils Act 1909?

The Indian Councils Act of 1909 introduced significant changes in the legislative structure of British India. Popularly called the Morley–Minto Reforms, this Act expanded the councils, increased Indian participation, and—most controversially—introduced separate communal electorates for Muslims. These reforms aimed to balance administrative efficiency with political appeasement but ended up altering the trajectory of Indian nationalism forever.

Why Is This Act Historically Important?

The reforms of 1909 were the first official acknowledgment of India’s demand for representation, yet they also institutionalized communal divisions. Understanding this Act helps us interpret the political calculations of the British Raj, the evolving stance of the Indian National Congress, and the roots of several debates that still shape modern democratic discourse in India.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Historical Background: The Political Climate Leading to the Indian Councils Act 1909

To understand the significance of the Indian Councils Act 1909, it is essential to revisit the political and social environment of early twentieth-century India. This was a time when nationalist consciousness was rising sharply, colonial authority was increasingly being questioned, and both British officials and Indian leaders were reshaping their strategies in response to a rapidly changing political landscape.

The Early 20th Century: Growing Nationalism and Public Awakening

By the late nineteenth century, India had already begun witnessing a strong wave of political awakening. The spread of Western education, growth of newspapers, emergence of social reform movements, and rising awareness about rights and representation encouraged Indians to question the legitimacy of British rule. The formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 provided a platform for educated Indians to voice their grievances and aspirations in an organized manner.

However, the early 1900s brought a dramatic shift. Two major developments reshaped the political scene: (1) ideological division within Congress into Moderates and Extremists, and (2) the rise of a more assertive and aggressive nationalist sentiment. The Partition of Bengal in 1905 became a flashpoint, triggering widespread protests, Swadeshi movements, boycotts, and an outpouring of anti-colonial anger across the nation. This period marked the beginning of mass political mobilization—something the British administration had not anticipated.

British Concerns: The Need to Maintain Control

Between 1905 and 1907, rising unrest unsettled the British government. The violent reactions, growing political unity among Indians, and public pressure made the colonial administration realize that some form of political concession was necessary to maintain stability. Yet these concessions were not intended to empower Indians, but rather to strategically weaken the nationalist movement.

The British recognized that if Congress continued gaining influence, the political balance in India would shift away from colonial control. To counter this, they sought a formula that would expand Indian participation but in a carefully controlled and divided manner. The objective was simple: “grant representation, but preserve power.” This thinking laid the foundation for the reforms to come.

The Formation of the Muslim League and the Demand for Separate Representation

A major event influencing the 1909 reforms was the formation of the All India Muslim League in 1906. The League’s leaders believed that Hindus and Muslims had distinct political interests and that Muslims required separate political safeguards.

This aligned perfectly with British interests. The colonial administration had long followed a policy of “Divide and Rule”. Encouraging separate religious identities served as a tool to dilute national unity and weaken the Indian National Congress. British officials intensified their communication with Muslim League leaders, resulting in growing support for the idea of separate communal electorates, which later became the most controversial provision of the 1909 Act.

The Roles of John Morley and Lord Minto

The Act is named after two key figures: John Morley (Secretary of State for India) and Lord Minto (Viceroy of India). Although both agreed on the need for reforms, their motivations differed.

Morley was comparatively liberal and believed that granting limited reforms could help build trust with educated Indians. He was convinced that some level of inclusion was necessary to maintain the moral legitimacy of British rule. In contrast, Lord Minto prioritized administrative stability over political ideals. He feared that growing nationalism could threaten British supremacy, and thus pushed reforms that would introduce participation without transferring real power.

Together, they crafted a policy that appeared progressive on the surface but was deeply conservative in its intent—offering Indians a taste of participation while ensuring British dominance remained unchallenged.

The Reaction of the Indian National Congress

The Congress had long demanded greater self-governance, so the announcement of reforms initially sparked hope. However, when the details emerged, it became evident that the reforms were designed more to contain nationalism than to encourage democratic empowerment.

Extremist leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak criticized the reforms sharply, calling them inadequate and deceptive. Moderates, on the other hand, viewed them as a small but essential step forward. This ideological split within Congress weakened the movement at a crucial moment, indirectly benefiting the colonial administration.

Summary: The Foundation of the 1909 Reforms

In summary, the Indian Councils Act 1909 emerged at a crossroads in India’s political evolution. Nationalist sentiment was rising, British anxiety was growing, and communal politics was being deliberately encouraged by the colonial administration. The reforms were introduced not to empower Indians, but to manage dissent, reinforce divisions, and maintain British supremacy.

Understanding this background is crucial, because it reveals the strategic motivations behind the Act and sets the stage for analyzing its provisions, impact, and long-term consequences—topics we explore in the following sections.

Key Provisions: Detailed Features of the Morley–Minto Reforms of 1909

The Indian Councils Act 1909 introduced a series of constitutional changes that reshaped the political structure of British India. Though presented as a step toward greater representation, the true purpose of the reforms was far more complex. Below is a detailed examination of its major provisions and the political intentions behind them.

1. Expansion of Legislative Councils

One of the most visible features of the Act was the expansion of both the Central Legislative Council and the Provincial Legislative Councils. The number of members was increased to project an image of widening participation. At the central level, Indian members were added in greater numbers than before, while provincial councils saw even larger expansions.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

However, this numerical growth did not translate into real political power. Most influential seats remained under British control, and several members continued to be nominated rather than elected. In essence, the councils grew in size but not in authority.

2. Limited but Symbolic Indian Participation

For the first time, selected Indian members were allowed to participate in discussions, ask questions, and debate public matters. This marked a symbolic entry of Indian voices into the administrative framework of the Raj. Indian members could criticize policies and analyze parts of the budget, giving the impression that the government was becoming more inclusive.

But the scope of this participation remained extremely restricted. Indians could not vote on crucial matters, nor influence executive authority. They were “heard” but not “empowered,” making this provision more cosmetic than transformational.

3. Introduction of Separate Communal Electorates

The most controversial and historically significant provision was the introduction of Separate Communal Electorates for Muslims. This meant Muslims would elect their representatives through exclusively Muslim electorates, ensuring reserved seats exclusively for Muslim candidates.

The British justified this by claiming it would safeguard minority interests. However, historians widely agree that this was a deliberate move to fragment India’s political unity and weaken the growing nationalist movement. The policy institutionalized communal identity in politics, laying the foundation for deeper divisions in the decades to come.

4. Expansion of the Legislative Discussion Space

The reforms broadened the scope of subjects on which council members could speak. Members were now permitted to raise discussions, criticize government decisions, and introduce supplementary questions. This created a limited arena for administrative accountability—something previously unheard of in colonial governance.

Despite this apparent openness, the government still controlled the agenda tightly. Sensitive subjects could not be discussed, and the presiding officials could shut down uncomfortable topics at will.

5. Increase in Nominated Members

Another provision was the deliberate increase in the number of nominated members. This offered the British a convenient mechanism to ensure that “loyal” and “cooperative” Indians remained part of the councils. These individuals were often landlords, businessmen, or administrative elites who had strong ties with the colonial government.

By manipulating the nomination process, the British ensured that real influence never left their hands, despite the appearance of diversity in the councils.

6. Property-Based and Restricted Voting Rights

Though elections were introduced at limited levels, voting rights remained heavily restricted. Eligibility was determined by property ownership, education, and social status. Only a tiny fraction of India’s population could vote, keeping the political process firmly in the hands of privileged groups.

This provision ensured that electoral outcomes would not challenge colonial authority or empower popular movements.

7. Minor Step Toward Provincial Self-Governance

The Act made small adjustments in the direction of provincial self-governance by granting provincial councils a slightly larger role in administrative matters. However, this autonomy was more symbolic than real. Provincial governors retained veto powers and exercised significant authority over all major decisions.

This provision laid early groundwork for later reforms (such as the 1919 and 1935 Acts), but the 1909 version remained highly conservative.

Summary: The Hidden Intent Behind the Provisions

When examined collectively, the provisions of the Morley–Minto Reforms reveal two complementary objectives: (1) to give Indians a sense of partial participation without shifting actual power, and (2) to engineer political and communal divisions that would strengthen British control. While the Act expanded representation in appearance, it tightened control in practice.

These provisions not only shaped the legislative landscape of the early 20th century but also set the stage for long-term political tensions. The next sections—Impact, Long-Term Effects, and Criticism—help reveal how deeply these reforms influenced India’s constitutional journey.

Immediate Impact: The Direct Political Effects of the 1909 Reforms

The implementation of the Indian Councils Act 1909 brought several immediate changes to the Indian political environment. While some developments appeared progressive on the surface, many carried deeper implications that altered the country’s political direction. This section explores the direct and short-term consequences that emerged right after the reforms were introduced.

1. A Visible but Limited Increase in Indian Representation

One of the earliest impressions created by the reforms was the expansion of Indian participation in legislative councils. The British government promoted this as a major step toward involving Indians in governance. Newly appointed Indian members began asking questions, participating in debates, and raising limited criticisms of government actions.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

However, this representation was more cosmetic than substantial. Indians could speak, but they could not influence decisive policy matters. The executive authority—held firmly by British officials—remained untouched. Thus, the increase in representation created an “illusion of empowerment” rather than actual political transformation.

2. Strengthening of the Muslim League’s Political Position

The introduction of Separate Communal Electorates immediately elevated the political standing of the All India Muslim League. With Muslims receiving their own dedicated electoral arrangements, the League now had an official channel through which it could communicate its demands and negotiate with the colonial administration.

This development significantly weakened the Indian National Congress, which until then projected itself as the representative body of all Indians. The reforms made it clear that Indian politics was beginning to split along communal lines—a trend that would have far-reaching consequences.

3. Internal Tensions Within the Indian National Congress

The reforms intensified ideological differences within Congress. Extremist leaders sharply criticized the Act, arguing that the reforms deceived Indians by offering symbolic participation instead of real power. Moderates, however, viewed the changes as a gradual step forward that could lead to future reforms.

These disagreements weakened the organizational unity of the Congress. Over the next few years, the divide between Moderates and Extremists became more pronounced, creating space for British authorities to control the political situation more effectively.

4. The Illusion of British Goodwill

Many Indians initially believed that the British were genuinely responding to India’s growing political aspirations. The reforms were celebrated by some as the beginning of a new partnership between the rulers and the ruled.

This optimism, however, faded quickly. It soon became evident that the councils had no real influence on critical policies or budgetary decisions. The British continued to retain executive supremacy. As the initial excitement waned, Indians realized that the reforms were designed more to pacify dissent than to empower them.

5. Formal Beginning of Communal Politics

Perhaps the most profound immediate impact was the formal introduction of communal identity into electoral politics. The recognition of Muslims as a separate political entity by law changed the nature of Indian politics permanently. It encouraged political mobilization based on religious identity rather than shared national interests.

This shift weakened the prospect of a unified nationalist movement and fueled future demands for greater communal protections. The seeds of political division planted by the 1909 reforms soon grew into much larger conflicts in later decades.

Summary: More Confusion than Progress

In summary, the immediate impact of the 1909 reforms revealed a contradictory picture— increased representation but unchanged power structures, rising hopes but deeper divisions, and reforms that promised progress but delivered uncertainty. The Act shaped the early 20th-century political landscape in ways the British had intended: controlled participation, managed dissent, and a divided nationalist movement.

These short-term effects laid the foundation for long-term political shifts that would later transform India’s struggle for independence.

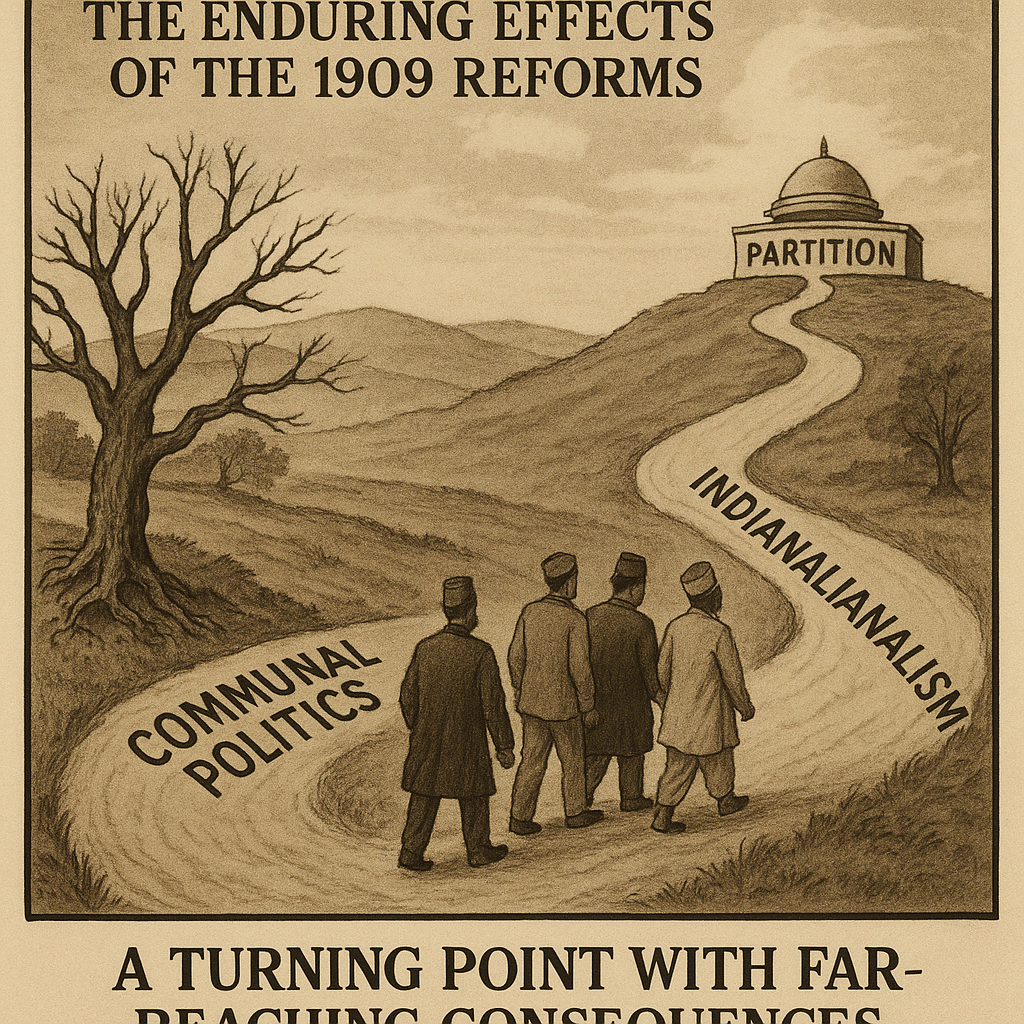

Long-Term Impact and Political Consequences: The Enduring Effects of the 1909 Reforms

While the immediate effects of the Indian Councils Act 1909 were visible soon after its implementation, its long-term consequences were far more profound. The Act altered the course of Indian politics, deepened social divisions, and shaped the framework of constitutional development for decades to come. This section explores how the reforms left a lasting imprint on India’s political journey.

1. Deep Entrenchment of Communal Politics

The most significant long-term impact of the Act was the institutionalization of communal politics. By introducing Separate Communal Electorates for Muslims, the British government formalized religious identity as a political category. This marked the beginning of a political system where communities were encouraged to think, vote, and organize along communal lines.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Over the following decades, this divide became sharper. The reforms influenced later developments such as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms of 1919, the Communal Award of 1932, and even the debates within the Constituent Assembly. Many historians argue that the roots of the eventual partition of India can be traced back to this moment, when communal identity became politically institutionalized.

2. Weakening of the Indian National Congress

The Act intensified ideological differences within the Indian National Congress. Extremists condemned the reforms as deceptive and divisive, while Moderates believed they were a step toward gradual constitutional advancement. These conflicting viewpoints weakened the unity of the Congress.

This internal polarization had long-term consequences. A divided Congress struggled to present a unified nationalist strategy, especially during critical phases of the independence movement. The British administration exploited this division effectively, slowing down the momentum of the national struggle for several years.

3. Rise of the All India Muslim League as a National Force

The reforms significantly boosted the political legitimacy of the All India Muslim League. With separate electorates, the League gained official recognition as the political representative of Indian Muslims. This transformed it from a newly formed organization into a key player in Indian politics.

Over time, the League’s growing influence created a dual-power structure in Indian politics—one led by the Congress and the other by the Muslim League. This duality shaped political negotiations and debates for the next four decades, eventually contributing to the call for Pakistan in the 1940s.

4. Growth of Provincial Politics and a Step Toward Federalism

The reforms indirectly encouraged the rise of provincial political identities. With expanded provincial councils, leaders began engaging more deeply with local issues such as land revenue, education, infrastructure, and social welfare. This fostered the early seeds of federal political thinking in India.

Later reforms, including the Government of India Acts of 1919 and 1935, built upon this foundation. Thus, while the 1909 Act did not grant true provincial autonomy, it helped introduce the idea that provinces could be political units with distinct interests.

5. Expansion of Political Consciousness and Emergence of New Leadership

Although the Act restricted real political power, it unintentionally expanded political awareness among Indians. Educated Indians increasingly realized that the British were unwilling to share meaningful power, which in turn fueled nationalist sentiment.

This period witnessed the emergence of influential leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Mahatma Gandhi, each shaping political discourse in distinct ways. The struggle for rights evolved from petitions to organized mass movements, and the fight for representation transformed into a demand for self-rule.

6. Foundation for Future Constitutional Reforms

The 1909 reforms established a pattern the British would follow for the next several decades—granting limited concessions to control political unrest while preserving imperial authority. The Act demonstrated how the government preferred slow, carefully managed constitutional change rather than meaningful power-sharing.

This created a trajectory that led to successive constitutional milestones: the 1919 reforms, the 1935 reforms, and finally, the negotiations leading to independence. In this sense, the 1909 Act laid the foundation for both the constitutional development of India and the political conflicts that shaped the independence movement.

Summary: A Turning Point with Far-Reaching Consequences

In summary, the Indian Councils Act 1909 had effects far beyond its immediate implementation. It altered the nature of Indian politics, deepened communal divisions, reshaped political institutions, and changed the balance of power between national groups. The Act did not just reform councils—it redefined the political future of India.

The long-term consequences of the Act demonstrate how a seemingly limited constitutional change can influence an entire nation’s destiny. Its legacy can be traced throughout the independence movement and even in contemporary discussions on representation and communal politics.

Criticism and Alternative Perspectives: Evaluating the Limits and Interpretations of the 1909 Reforms

The Indian Councils Act 1909, often showcased by the British as a major constitutional advance, has been widely criticized by nationalist thinkers, political historians, and modern scholars. While the reforms introduced certain structural changes, their deeper intent and consequences reveal a complex and controversial chapter of colonial policymaking. This section explores the major criticisms and the alternative viewpoints that help us understand the Act more holistically.

1. Absence of Real Power Transfer

The most prominent criticism of the Act was that it expanded representation without redistributing actual power. Indians were allowed to sit in legislative councils, but their roles remained largely symbolic. They could raise questions and participate in debates, yet they lacked any meaningful authority over executive decisions.

Many contemporary critics described the reforms as “a façade of constitutional progress” —a political tactic designed to pacify Indian demands without sharing genuine control.

2. The Clearest Expression of ‘Divide and Rule’

The introduction of Separate Communal Electorates for Muslims was viewed as the colonial government’s most explicit attempt to divide Indian society. Critics argued that this provision institutionalized religious divisions and encouraged political mobilization along communal lines, weakening the broader project of national unity.

This structural division in the electorate laid the groundwork for deeper communal tensions, which later influenced the Communal Award (1932), the politics of the 1940s, and ultimately the Partition.

3. Weakening of the Indian National Congress

Another major criticism was that the reforms were intentionally crafted to undermine the Indian National Congress. By offering limited seats to select Moderates, the British created internal tensions within the party. Extremists denounced the Act as deceptive, while Moderates welcomed it as an incremental achievement.

This ideological divide weakened Congress’s ability to provide unified leadership to the nationalist movement—an outcome that clearly favored the colonial administration.

4. Restriction Rather Than Growth of Political Consciousness

Several scholars argue that the limited debating powers and controlled agenda of the councils actually restricted the organic growth of democratic political culture. Discussions were carefully monitored, sensitive subjects were prohibited, and executive authority remained immune to legislative scrutiny.

In this view, the reforms slowed India’s political evolution rather than accelerating it.

Alternative Perspective: A Necessary First Step?

Despite widespread criticism, some historians offer an alternative interpretation. They argue that although the 1909 reforms were inadequate, they played an important foundational role in India’s constitutional development. The Act introduced Indians—however minimally—to legislative procedures, accountability mechanisms, and structured political debate.

According to this perspective, the experience gained through these limited reforms helped prepare Indian leaders for greater political responsibilities in the 1919 and 1935 reforms, and eventually contributed to the evolution of democratic thinking during the freedom struggle.

Summary: A Complex and Controversial Reform

Overall, the criticism and alternative perspectives highlight that the 1909 Act was neither wholly progressive nor entirely regressive. It represented a calculated attempt by the British to maintain control while offering limited concessions. The reforms deepened communal divisions, restricted meaningful empowerment, and weakened nationalist unity—yet they also opened a narrow doorway toward constitutional participation.

The truth lies somewhere in between: the Act was a flawed but consequential moment in India’s political history, shaping debates on representation, identity, and governance for decades to come.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Personal Learning and Narrative: How History Transformed My Understanding

My journey through the Indian Councils Act 1909 was not just an academic exploration. It became a deeply personal experience—one that reshaped my understanding of politics, identity, unity, and the fragile foundation upon which nations evolve. This narrative reflects the thoughts, realizations, and emotional insights I gained while studying one of the most consequential reforms in India’s colonial history.

1. A Chance Encounter with a Forgotten Chapter

My story begins with a dusty, almost forgotten book lying in a corner of an old library. When I opened it, a small chapter titled “The Indian Councils Act 1909” caught my eye. Below it was a striking line: “The Birth of Communal Politics in India.”

At that moment, I wondered— “Can one law truly influence the destiny of a nation?” I had read about reforms, acts, and constitutional changes before, but this particular question opened a new door of curiosity. Slowly, I began to see not just a political change, but a shift in the psychology of a society struggling under colonial rule.

2. A Question That Changed My Perspective

As I continued reading debates, letters, and commentaries from that period, one question kept troubling me: “Was India already divided before 1909, or did this Act deepen those lines?”

This question led me to understand that divisions—religious, social, economic—existed long before the Act. But the reforms strengthened these divisions by giving them legal expression. It made me realize how fragile unity is, and how quickly political structures can transform society—sometimes without people even noticing.

3. Leaders, Their Emotions, and the Weight of Decisions

When I studied the arguments of leaders like Morley, Minto, Tilak, Gokhale, Jinnah, and others, I felt the human side of history. The British leaders were driven by fear of losing control; Indian Moderates hoped for gradual progress; Extremists demanded dignity and rights.

Through these narratives, I learned that history is rarely about absolute right or wrong. It is about fear, courage, compromise, risk, and the dreams people carry. Each leader was responding to the circumstances they faced—yet their decisions would shape millions of lives long after they were gone.

4. My Biggest Realization — Division Begins Slowly

The most powerful insight I gained was this: Division in society does not happen suddenly; it grows silently.

The 1909 reforms were not a dramatic event. They looked small, almost harmless—just an administrative adjustment. Yet they sowed seeds of communal thinking that would later grow into mistrust, conflict, and eventually Partition.

This taught me that every policy, every decision, and every public message matters. A nation’s unity depends not only on its big events but also on its subtle shifts in political language, representation, and public perception.

5. Lessons for Today's India

As I look at modern India—its elections, debates, alliances, and identity-driven politics—I often think back to 1909. The echoes of that Act can still be felt today. It reminds me that democracy is fragile and must be protected through dialogue, trust, and inclusiveness.

The lesson I carry is: Representation must unite, not divide. Politics must empower, not manipulate. History must guide, not repeat itself.

Summary: How History Changed Me

Reading about the Indian Councils Act 1909 changed me more than I expected. It taught me that history is not the story of rulers alone—it is the story of ordinary people affected by the decisions of those in power.

This narrative helped me see that the shape of a nation is defined not only by major revolutions but by small choices made in quieter moments. And that is the greatest learning I carry forward: even a minor reform can redirect the future of an entire country.

Conclusion and Lessons for Today: Reflections from a Defining Chapter

The Indian Councils Act 1909 was far more than a constitutional adjustment—it marked a turning point in India’s political evolution. It reshaped governance, formalized communal identity in politics, and influenced the direction of the freedom movement. Understanding this chapter is essential not only for appreciating the past but also for interpreting the challenges of the present.

1. Small Decisions Can Reshape a Nation

One of the biggest lessons the 1909 reforms teach us is that seemingly minor political decisions can lead to profound long-term consequences. The introduction of separate communal electorates appeared to be a limited, administrative measure at that time—but it sowed seeds of division that influenced India’s politics for decades. This reminds us that policymakers must always consider the deeper social impact of every reform.

2. Unity Thrives on Dialogue and Trust

The Act also demonstrates how quickly unity can weaken when representation becomes identity-based rather than inclusive. In a diverse democracy like India, this lesson is more relevant than ever: national strength grows when every community feels heard, valued, and connected—not segregated. Dialogue, cooperation, and trust remain the cornerstones of a stable and resilient society.

3. Democracy Requires Awareness and Responsibility

The 1909 reforms made it clear that formal representation without real empowerment is insufficient. True democracy grows when citizens are informed, engaged, and willing to claim their rights. The freedom movement that followed proved that transformative change emerges from collective participation, not symbolic concessions.

Summary: The Past Illuminates the Future

Ultimately, the Indian Councils Act 1909 reminds us that history is not merely a record—it is a guide. It teaches that a nation’s future depends on unity, inclusive governance, and the courage to challenge divisive structures. If we learn from the past and remain committed to building equitable systems, democracy will continue to grow stronger and more meaningful for every citizen.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Here are some important questions and detailed answers that help clarify the context, impact, and relevance of the Indian Councils Act 1909 (Morley–Minto Reforms).

1. What was the primary objective of the Indian Councils Act 1909?

The primary stated objective of the 1909 Act was to expand Indian participation in legislative councils and give educated Indians a limited role in governance. However, its deeper political motive was to manage increasing nationalist pressure without transferring real power. While more Indians were included in councils, they were largely restricted to asking questions and debating issues without any authority over executive decisions. Thus, the Act aimed to create an impression of political progress while ensuring that the British administration retained full control over key policies. It was a strategic move to soften nationalist criticism, not empower India politically.

2. Why were Separate Communal Electorates considered controversial?

Separate Communal Electorates were controversial because they legally institutionalized religious identity as the basis of political representation. Muslims could vote only for Muslim candidates in reserved constituencies, which strengthened communal divisions and encouraged identity-based politics. Critics argued that this was a deliberate British strategy under “Divide and Rule” to weaken Indian nationalism. This provision planted long-lasting seeds of distrust between communities and ultimately contributed to the widening political divide that shaped later events such as the Communal Award (1932), separatist demands, and the Partition of India. It remains one of the most criticized aspects of the 1909 Act.

3. Did the Morley–Minto Reforms strengthen or weaken the Indian freedom movement?

The reforms had a dual effect. On one hand, they exposed the limitations of British “reforms” and made Indians realize that real power would not be granted easily. This increased political awareness, sharpened nationalist resolve, and encouraged broader public participation in the freedom struggle. On the other hand, the introduction of communal electorates and limited concessions created divisions within the Indian National Congress, widened the gap between Moderates and Extremists, and politically empowered the Muslim League. Thus, the reforms both stimulated the demand for independence and simultaneously weakened the unity of the movement.

4. What were the long-term political consequences of the 1909 reforms?

The long-term consequences were far-reaching. The Act laid the foundation for communal politics by making religion a formal criterion for political representation. It strengthened the Muslim League, weakened the Congress internally, and significantly altered the structure of legislative politics. Additionally, the reforms initiated the slow evolution of provincial politics and paved the way for later constitutional developments such as the Acts of 1919 and 1935. Many historians believe that the roots of Partition can be traced to the communal provisions introduced in 1909.

5. What lessons can modern India learn from the Indian Councils Act 1909?

Modern India can derive several key lessons from the 1909 reforms. First, identity-based political structures—whether religious, caste-based, or sectional—can have deep and long-lasting consequences. Second, meaningful political empowerment must be inclusive, transparent, and rooted in public trust. Third, unity in a diverse nation depends on dialogue and equal representation, not segregation. The Act reminds us that even small political decisions can redefine national identity and steer history in unexpected directions. Therefore, policies today must be designed with long-term social harmony and democratic strength in mind.

References

The following primary and secondary sources were consulted to ensure the accuracy, context, and depth of this article on the Indian Councils Act 1909 (Morley–Minto Reforms). Replace placeholder links with actual URLs if needed.

- Indian Councils Act, 1909 — Official Document

Primary legal text from British Government archives.

[Full Act Text — Link] - British Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Debates and statements by John Morley and Lord Minto related to the 1909 reforms.

[Hansard Debate — Link] - Bipin Chandra — Modern Indian History

Chapters on nationalist movements and colonial constitutional reforms.

Reference: Bipin Chandra, History of Modern India (Publisher, Year). - Ayesha Jalal and Contemporary Scholars

Analytical works on communal politics, constitutional developments, and early 20th-century India.

Example: Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman. - NCERT & Academic Resources

Concise summaries, timelines, and exam-oriented explanations for quick reference.

[NCERT Resource — Link] - Secondary Sources: Journals & Archives

University repositories, scholarly papers, and historical archives used for cross-verification.