Introduction — The Himalayas: A Living Miracle of Nature

The Himalayas are not merely a mountain range; they are a living chapter of Earth's geological history, a guardian of ecosystems, and a cradle of ancient civilizations. Stretching across several countries and covering thousands of kilometers, the Himalayas shape the climate, nurture major rivers, and influence the cultural identity of millions of people. Their presence is so grand and powerful that they are often referred to as the “Roof of the World” — a monumental natural wall that defines the physical and spiritual landscape of Asia.

The origin of the Himalayas dates back millions of years, when the Indian Plate drifted northward and collided with the Eurasian Plate. This massive continental collision caused the Earth's crust to fold, rise, and form what we now recognize as the majestic Himalayan range. Remarkably, this process is still ongoing, which makes the Himalayas one of the world’s youngest and most dynamic mountain systems. Every year, they continue to rise slightly, symbolizing the restless and ever-evolving nature of our planet.

Beyond their geological significance, the Himalayas serve as the birthplace of Asia’s great rivers — including the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus — providing water, livelihood, and hope to countless communities. Culturally, the region has been associated with spiritual traditions, sacred temples, and ancient wisdom for thousands of years. In this article, we will explore the origin, geological structure, ecological significance, cultural value, and contemporary challenges that make the Himalayas one of the most extraordinary creations of nature.

|

Product Name HereShort product description goes here. Highlight key features or benefits. |

| Buy on Amazon |

Origin of the Himalayas — A Marvel of Plate Tectonics

The origin of the Himalayas is one of the most remarkable and scientifically fascinating events in the geological history of Earth. This magnificent mountain range, stretching across thousands of kilometers, is the result of millions of years of tectonic movements, continental drift, and powerful geological collisions. The Himalayas stand as a living testimony to the dynamic nature of our planet, constantly reminding us that Earth is not static but continuously evolving.

1. The Northward Journey of the Indian Plate

Around 200–250 million years ago, the Earth had a massive supercontinent known as Gondwana. This landmass included present-day India, Africa, Australia, Antarctica, and parts of South America. Due to convection currents inside the Earth’s mantle, Gondwana began to break apart, and slowly, the Indian Plate separated and started moving steadily toward the north.

What makes this journey extraordinary is the speed of the Indian Plate. Compared to other continental plates, the Indian Plate moved unusually fast — nearly 15–20 centimeters per year. Such a high velocity is rare in geological history and played a significant role in the powerful collision that ultimately gave birth to the Himalayas. Scientists still find this rapid movement impressive and consider it one of the fastest continental drifts ever recorded.

2. The Great Collision: Indian and Eurasian Plates

About 50 million years ago, the Indian Plate finally collided with the Eurasian Plate. This was not a gentle meeting of continents but a massive geological impact. Both plates were continental, thick, and made of light crust, which meant that neither plate could easily sink beneath the other. Instead, the collision caused the land to fold, crumple, and rise upward, giving birth to the initial Himalayan formations.

The collision was so powerful that it pushed layers of sedimentary rocks, which were once part of the ancient Tethys Sea, upward to form towering mountains. Even today, fossils of marine organisms and seashells are found in the higher regions of the Himalayas, including near Mount Everest. These discoveries are strong evidence that the peaks we admire today were once submerged under ancient oceans.

3. Ongoing Formation: A Mountain Range Still Rising

The origin of the Himalayas was not a single event but a long and continuous process. Even after the initial collision, the Indian Plate did not stop pushing northward. It continues to move approximately 5 centimeters per year, which means the Himalayas are still growing. Every year, the range rises a few millimeters as the continental plates continue to push against each other.

This ongoing activity is the reason why geologists call the Himalayas a “young mountain range.” Unlike older and more eroded mountains, the Himalayas are dynamically changing, reshaping their landscapes through tectonic uplift, erosion, landslides, and seismic activity. Frequent earthquakes in the Himalayan region are also a direct result of the continuous pressure between the Indian and Eurasian plates.

4. Geological Layers of the Himalayas

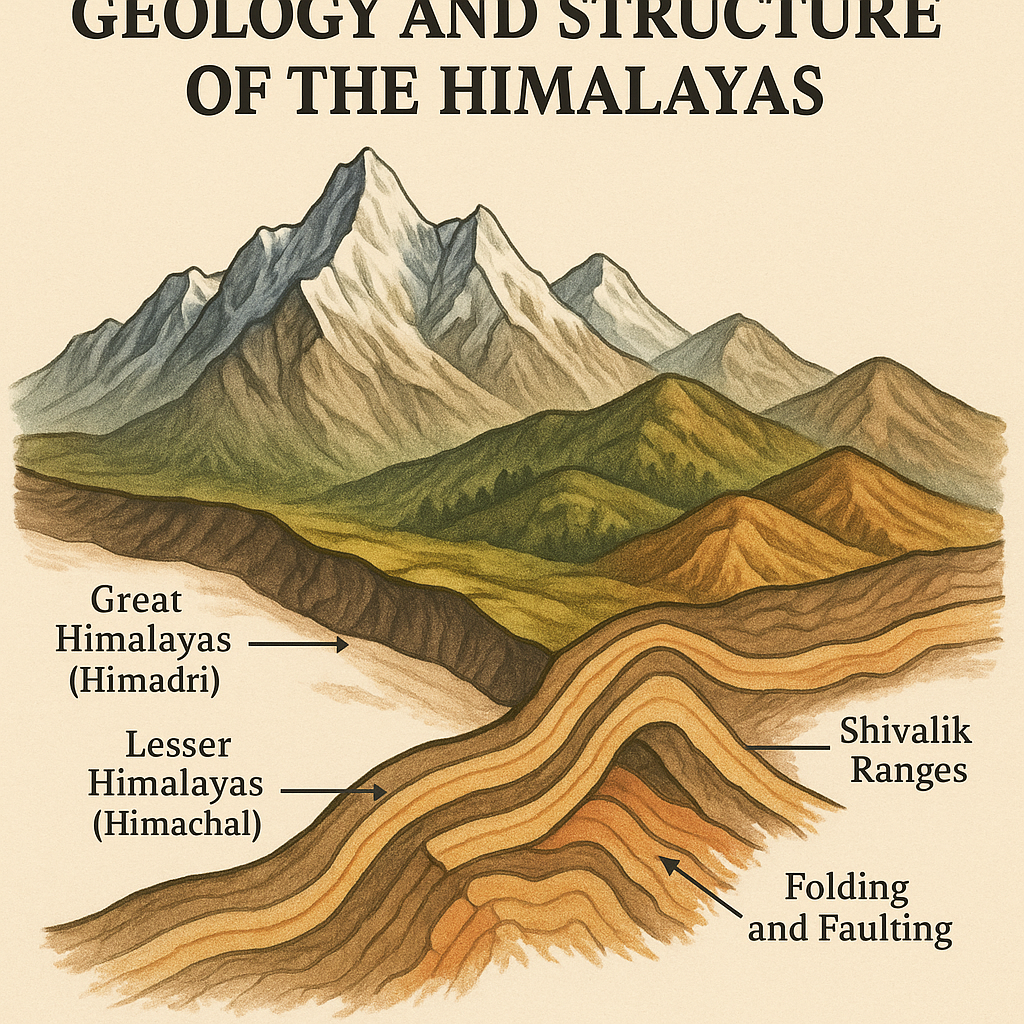

The Himalayan range is broadly divided into three major zones: the Great Himalayas (Himadri), the Lesser Himalayas (Himachal), and the Shivalik ranges. Each zone reflects a different stage of geological evolution and structural formation.

The Great Himalayas consist of some of the highest peaks in the world, including Mount Everest and Kanchenjunga. These peaks are composed primarily of ancient crystalline rocks and metamorphic formations. The Lesser Himalayas, located just south of the Great Himalayas, include forested slopes, deep river valleys, and inhabited regions. The Shivalik range, the outermost Himalayan belt, is made mostly of younger sediments carried by rivers and deposited during the uplift process.

Together, these geological zones show that the Himalayas were not formed at once but developed through multiple stages of folding, faulting, uplifting, and erosion. Each layer tells a different story — from ancient sea floors to rising mountain peaks — making the Himalayas a natural geological museum.

5. From Ocean Floor to the Roof of the World

One of the most astonishing facts about the Himalayas is that the rocks found on the highest peaks were once part of the ocean floor. This dramatic transformation from seabed sediments to snow-covered mountain peaks highlights the sheer power of tectonic forces. The Himalayan journey from ocean to sky is not only a scientific wonder but also an inspiring symbol of how nature reshapes itself over millions of years.

Today, when we look at the majestic Himalayan landscape, we are witnessing the result of one of Earth’s greatest geological transformations. The continuous rise, shifting landforms, and dynamic environment show that the story of the Himalayas is still being written. Their origin is a reminder that the Earth is alive, restless, and ever-changing.

Geology and Structure of the Himalayas

The geology of the Himalayas is one of the most complex and fascinating subjects in Earth sciences. This vast mountain system is not merely a collection of high peaks and deep valleys; it is a layered geological archive that preserves the secrets of continental drift, tectonic forces, ancient oceans, and ongoing crustal movements. Understanding the geological structure of the Himalayas provides deep insight into how the planet has evolved over millions of years and how powerful natural forces continue to shape the landscape.

1. The Three Major Geological Divisions

Geologists classify the Himalayas into three major structural zones — the Great Himalayas (Himadri), the Lesser Himalayas (Himachal), and the Shivalik Ranges. Each zone is distinct in terms of rock type, age, altitude, climate, and landscape. Together, they form a continuous chain that stretches across India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Pakistan.

1.1 The Great Himalayas (Himadri)

The Great Himalayas form the innermost and highest part of the entire range. This region contains the world’s tallest peaks, including Mount Everest, Kanchenjunga, Lhotse, and Nanda Devi. The rocks found here are predominantly ancient crystalline rocks such as granite, gneiss, and high-grade metamorphic formations. These rocks were subjected to intense heat and pressure deep within the Earth before being pushed upward during the tectonic collision. Because of their hardness and resistance to erosion, the Great Himalayas appear sharper and more rugged than the outer ranges.

1.2 The Lesser Himalayas (Himachal)

Located south of the Great Himalayas, the Lesser Himalayas consist of lower mountain ranges, forested slopes, and inhabited valleys. Popular hill regions such as Shimla, Mussoorie, Darjeeling, and parts of the Kashmir Valley fall within this zone. The geology here is more diverse, containing a mixture of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. The region is characterized by river-cut valleys, lush vegetation, and frequent landslides due to its relatively softer rocks and complex tectonic structure.

1.3 The Shivalik Ranges

The Shivaliks represent the outermost and geologically youngest part of the Himalayas. These hills are typically 600–1500 meters in height and are composed mainly of unconsolidated sediments such as sandstone, conglomerates, gravel, and clay. These materials were deposited by ancient rivers and later uplifted due to tectonic activity. Because of their loose structure, the Shivaliks experience high rates of erosion and are prone to flash floods and slope failure.

2. Formation Through Folding and Faulting

The Himalayas are classified as “fold mountains,” which means they were formed through the folding and uplift of the Earth’s crust. When the Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate, enormous compressional forces acted on the rock layers. Instead of sinking, the crust buckled and folded, creating a series of parallel mountain belts. Several large-scale thrust faults, such as the Main Central Thrust (MCT), Main Boundary Thrust (MBT), and Himalayan Frontal Thrust (HFT), played a crucial role in shaping the structure of the mountains.

These geological faults continue to remain active even today. The constant pressure between the plates generates stress within the crust, making the Himalayan region one of the most earthquake-prone areas in the world. This ongoing tectonic activity explains why the Himalayas continue to rise by a few millimeters each year.

3. Diversity of Rock Types

The Himalayas display an extraordinary variety of rocks, reflecting their long geological history. Some of the major rock types include:

- Granite and gneiss — hard metamorphic rocks found mainly in the Great Himalayas.

- Quartzite — a tough, glittering mineral-rich rock formed from sandstone.

- Limestone and shale — sedimentary rocks containing fossils of ancient marine organisms, evidence of the Tethys Sea.

- Sandstone and conglomerates — common in the Shivalik region, deposited by rivers and floods.

Many of these rocks preserve fossils that confirm the Himalayas once formed the seabed of the ancient Tethys Ocean. This is one of the most powerful proofs of continental drift and tectonic uplift in Earth’s history.

4. Rivers and Valleys: Sculptors of the Himalayas

The formation of the Himalayan landscape is heavily influenced by major river systems such as the Ganges, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, and Indus. These rivers carve deep valleys, create gorges, transport sediments, and shape the mountains continuously through erosion. Over millions of years, the action of river water has produced diverse landforms such as U-shaped glacial valleys, V-shaped river valleys, alluvial fans, and wide terraces where human settlements thrive.

|

Product Name HereShort product description goes here – key features, benefits or USP. |

| Buy on Amazon |

5. A Geologically Active Region

Because the Indian Plate continues to push northward, the Himalayas remain geologically active. This results in frequent earthquakes, landslides, rockfalls, and slope failures. Regions such as Nepal, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Kashmir experience recurring seismic events, indicating that the collision process is ongoing. This dynamic activity ensures that the Himalayas are still rising, making them one of the youngest and fastest-growing mountain ranges in the world.

6. The Himalayas: A Geological Archive

Scientists often refer to the Himalayas as a “geological museum of Earth.” Every layer, fossil, and rock formation tells a story — from ancient oceans and drifting continents to dramatic mountain-building events. The immense geological diversity makes the Himalayas a globally important site for researchers, students, and environmental scientists.

Overall, the geology and structure of the Himalayas reveal the raw power of natural forces and the long, complex processes that shape our planet. The Himalayas are not just mountains; they are a dynamic, evolving creation that continues to rise, shift, and transform — carrying within them millions of years of Earth’s history.

Ecology and Glaciers — The Lifeline of the Himalayas

The Himalayas are not only the tallest mountain range in the world but also one of the most important ecological systems on Earth. Their forests, rivers, glaciers, wildlife, and climate zones support millions of people across Asia. Due to their enormous ecological impact, the Himalayas are often referred to as the “Ecological Heart of Asia.” From sustaining major rivers to influencing rainfall patterns and from protecting unique biodiversity to providing life-supporting natural resources, the Himalayan ecosystem plays a vital role in environmental balance. Understanding its ecology and glaciers helps us appreciate how significant this region is for life on Earth.

1. Himalayan Biodiversity — A Treasure of Life

The Himalayan region is one of the richest biodiversity hotspots in the world. Due to the vast altitude range—from foothills to high alpine zones—the Himalayas host a dramatic variety of habitats. As one moves upward in elevation, the ecological zones change rapidly: from subtropical forests to temperate woodlands, alpine meadows, and finally to cold, barren tundra-like regions at extreme heights. Each zone shelters plant and animal species uniquely adapted to its climate.

The Himalayas are home to iconic and rare species such as the snow leopard, red panda, Himalayan black bear, musk deer, Himalayan monal, and several species of pheasants. Many of these species are endangered and require continuous conservation efforts. The region also contains thousands of medicinal plants, including highly valued herbs used in Ayurveda and Tibetan medicine. Forests of pine, deodar, birch, juniper, and rhododendron dominate large parts of the terrain, forming the backbone of the Himalayan ecosystem.

2. Glaciers — The Water Towers of Asia

The most remarkable feature of the Himalayas is their glaciers. With more than 9,000 glaciers, the Himalayas store one of the largest supplies of freshwater outside the polar regions. Because of this, they are often called the “Third Pole” or the “Water Towers of Asia.” These glaciers feed some of the most important rivers of the continent, including the Ganges, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, Indus, Sutlej, and their tributaries.

During summer, as temperatures rise, glaciers melt and release water, ensuring a continuous flow in major rivers even in dry months. This steady supply of water supports drinking needs, agriculture, hydropower, and ecosystems throughout South Asia. Without Himalayan glaciers, many countries—including India, Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh—would face severe water shortages.

Some of the most famous Himalayan glaciers include the Siachen Glacier, Gangotri Glacier, Zemu Glacier, Milam Glacier, and Yamunotri Glacier. The Gangotri Glacier is the primary source of the Ganges, one of the most sacred and economically important rivers of India. The Siachen Glacier, one of the largest non-polar glaciers in the world, stretches across an inhospitable terrain and remains frozen year-round.

|

Product Name HereAdd a short description here — key features or product highlight. |

| Buy on Amazon |

3. Impact of the Himalayas on Climate

The Himalayas play a major role in shaping the climate of South Asia. Acting like a giant natural barrier, they block icy winds from Central Asia, preventing northern India from becoming extremely cold during winter. At the same time, the Himalayas capture moisture-laden monsoon winds that blow from the Indian Ocean. When these winds collide with the towering mountain walls, they rise, cool, and form dense clouds, producing heavy rainfall across northern and northeastern India.

This climate-regulating ability of the Himalayas is the reason why the Indo-Gangetic plains are so fertile. The Himalayas also create rain-shadow zones, such as the Tibetan Plateau, where rainfall is minimal. This contrast in climate regions highlights the mountain range's immense influence over weather and agriculture.

4. Role of the Himalayas in the Water Cycle

The Himalayas are central to the hydrological cycle of South Asia. Their forests absorb rainfall, recharge groundwater, and stabilize soil. Glaciers release meltwater gradually, ensuring stable water flow in rivers. Snowpacks accumulate in winter and melt in spring, contributing to seasonal water availability.

The forests act as natural sponges, capturing moisture and preventing excessive runoff. This reduces the risk of floods during heavy rainfall and maintains river flow during dry periods. Without these natural mechanisms, the entire region would face severe extremes—prolonged droughts or devastating floods.

5. Climate Change and Its Impact on Himalayan Glaciers

In recent decades, climate change has severely affected the Himalayas. Rising temperatures have accelerated glacier melting at unprecedented rates. According to scientific studies, many Himalayan glaciers are retreating by 10–60 meters per year. The Gangotri Glacier alone has shrunk by nearly 1.5 kilometers in the past 70 years.

The melting of glaciers poses a serious threat to water security for millions of people. If glaciers continue to shrink, river flow could drastically decrease in the long run, affecting agriculture, drinking water, and hydropower production. Rapid melting also increases the risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), which can destroy villages, roads, and farms within minutes.

6. Threats to Himalayan Ecology

The delicate ecological balance of the Himalayas is under threat due to numerous factors:

- Rapid glacier retreat caused by global warming

- Landslides and soil erosion due to deforestation

- Unplanned construction of roads, tunnels, and hydropower projects

- Over-tourism and waste pollution

- Loss of habitat leading to wildlife decline

- Irregular rainfall and temperature fluctuations

These environmental pressures weaken the resilience of the Himalayan ecosystem and can lead to irreversible ecological damage if not addressed timely.

7. Conservation Measures — Securing the Future

Protecting the Himalayas requires a combination of scientific strategies, traditional wisdom, and community participation. Conservationists are promoting sustainable tourism, reforestation programs, glacier monitoring initiatives, and climate-friendly policies. Local communities are encouraged to adopt environmentally responsible practices, such as controlled grazing, organic farming, and watershed protection.

The future of the Himalayan ecosystem depends on our actions today. By reducing carbon emissions, protecting forests, managing waste, and respecting natural boundaries, we can ensure that the glaciers, rivers, and forests of the Himalayas remain healthy for generations to come. The Himalayas are not just mountains—they are the lifeline of an entire continent, and their preservation is a collective responsibility.

Cultural and Economic Importance of the Himalayas

The Himalayas hold immense cultural, spiritual, and economic significance for millions of people across South Asia. Far beyond being a geographical structure, the Himalayan region has served as a cradle of civilizations, a center of religious traditions, a source of livelihood, and a foundation of national identity. Its rivers nourish fields, its forests sustain communities, and its mountains inspire art, literature, and spiritual practices. Together, the cultural and economic importance of the Himalayas forms a powerful human–nature relationship that has existed for thousands of years.

1. Cultural Significance — The Spiritual Heart of Asia

The Himalayas are revered as the “Abode of the Gods” in Indian culture. For centuries, sages, saints, yogis, and seekers have come to these mountains for meditation and spiritual awakening. The Himalayas feature prominently in Hindu mythology, where they are associated with Lord Shiva, who is believed to reside at Mount Kailash. Numerous sacred rivers such as the Ganges, Yamuna, and Brahmaputra originate in this region, making it deeply sacred to millions of devotees.

Pilgrimage centers like Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, Yamunotri, Hemkund Sahib, Kailash–Mansarovar, and Amarnath attract devotees from across the world. These sites represent faith, endurance, purity, and devotion. Each valley and river has its own set of legends, folk tales, and traditional songs that reflect the long-standing bond between Himalayan communities and nature.

2. Indigenous Cultures and Mountain Communities

The Himalayas are home to diverse ethnic groups and tribal communities, including the Sherpas, Lepchas, Bhotias, Gaddis, Gujjars, and Ladakhis. Their cultures have evolved in harmony with the mountains, leading to unique traditions, languages, food habits, clothing, dances, and art forms. Many communities practice agriculture, animal husbandry, carpet weaving, wool production, and herbal medicine.

The social lives of these communities revolve around seasonal cycles, festivals, and nature worship. Celebrations such as Losar, Saga Dawa, Naga Panchami, and Kullu Dussehra reflect their close connection to the environment and spiritual values. These traditions embody the cultural richness of the Himalayas and preserve ancient wisdom passed down through generations.

3. Economic Importance — A Wealth of Natural Resources

Economically, the Himalayas are an invaluable resource. The region supports agriculture, forestry, hydropower, tourism, handicrafts, horticulture, and medicinal plant industries. Countries such as India, Nepal, and Bhutan rely heavily on Himalayan resources for food, energy, and economic growth. The rivers originating from the Himalayas create fertile plains that feed hundreds of millions of people.

4. Himalayan Rivers — Backbone of Agriculture and Livelihood

The Himalayan rivers play a major role in sustaining the economies of South Asia. Rivers such as the Ganges, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, Indus, Sutlej, and Beas support extensive irrigation networks that make the Indo-Gangetic plains some of the most productive agricultural zones in the world. These rivers ensure food security and support farming communities across several countries. Without Himalayan rivers, agriculture in northern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh would be severely affected.

5. Hydropower Generation — A Source of Clean Energy

|

Product Name HereAdd a short description here — key features or product highlights. |

| Buy on Amazon |

The steep gradients and fast-flowing rivers of the Himalayas make the region ideal for hydropower generation. Countries like India, Bhutan, and Nepal have developed major hydropower projects that contribute significantly to their national power supply. Hydropower not only meets local energy needs but also provides income through electricity exports. As the world shifts toward clean energy, Himalayan rivers will become even more important in providing sustainable power.

6. Tourism and Adventure Sports — A Major Economic Driver

Tourism is one of the largest industries in the Himalayan region. The breathtaking landscapes, snow-covered peaks, sacred sites, forests, lakes, and diverse cultures attract millions of tourists each year. Adventure activities such as trekking, mountaineering, skiing, paragliding, river rafting, camping, and high-altitude expeditions provide employment to thousands of local people.

Iconic trekking routes and climbing destinations — including the Everest Base Camp, Annapurna Circuit, Chadar Trek, Roopkund, and Valley of Flowers — draw international travelers and generate significant foreign exchange. Tourism also supports hotels, transportation, handicraft markets, and local cuisine industries, strengthening the mountain economy.

7. Medicinal Plants and Herbal Wealth

The Himalayas are rich in medicinal plants that are highly valuable in Ayurveda, Tibetan medicine, and modern herbal industries. Herbs such as jatamansi, kutki, atis, rhododendron, yarsagumba (cordyceps), and Himalayan thyme have significant commercial and therapeutic importance. Many local communities depend on the collection and sale of medicinal plants for their livelihood.

However, sustainable harvesting is essential to preserve these species for future generations. Overexploitation and habitat loss pose serious threats to the medicinal plant industry.

8. Strategic and National Security Importance

The Himalayas form a natural border between India and neighboring countries such as China, Nepal, Bhutan, and Pakistan. Their towering peaks and rugged terrain act as a strong defensive barrier, making them crucial for national security. Several military bases and monitoring posts are established across high-altitude regions like Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, and Sikkim.

The challenging terrain limits large-scale invasions and provides strategic advantages. This makes the Himalayas an essential part of geopolitical stability in the region.

9. Need for Cultural and Economic Balance

While the Himalayas contribute enormously to cultural heritage and economic development, they are also extremely fragile. Unplanned tourism, deforestation, overconstruction, and climate change are putting pressure on the region. Preserving the Himalayan environment is vital not only for its ecological health but also for protecting the cultures and economies that depend on these mountains.

Sustainable practices, responsible tourism, community-led conservation, and environmental awareness are essential for maintaining the delicate balance between human needs and natural systems.

Challenges and Conservation — Protecting the Himalayan Heritage

The Himalayas face a complex mix of environmental, social, and economic challenges. These mountains, which supply water, biodiversity, and cultural identity to millions, are under pressure from climate change, unplanned development, biodiversity loss, and increasing human activity. Conserving the Himalayan region demands coordinated action across governments, local communities, scientists, and visitors. The following section outlines the main challenges and practical conservation responses that can help secure the Himalayas for future generations.

1. Climate Change and Rapid Glacier Retreat

Rising global temperatures are causing Himalayan glaciers to retreat and shrink. This affects seasonal river flows, increases the risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), and threatens long-term water availability for agriculture, drinking water, and hydropower. Changes in snowpack and rainfall patterns also amplify droughts and floods, creating unstable conditions for people who depend on predictable water cycles.

2. Unplanned Infrastructure and Land Use Change

Road building, tunnel construction, mining, and large dams in fragile mountain terrain can destabilize slopes, increase erosion, and fragment habitats. Poorly sited buildings and shortcuts on hillsides accelerate landslides and sedimentation in rivers. Effective land-use planning and strict environmental impact assessments are necessary to minimize damage in seismically active mountainous zones.

3. Biodiversity Loss and Habitat Degradation

Deforestation for fuelwood, agricultural expansion, and illegal wildlife trade are eroding the Himalayas’ unique biodiversity. Iconic species and many endemic plants face shrinking habitats. Loss of forest cover weakens natural water regulation and increases soil erosion, undermining the ecological services that communities rely on.

4. Over-Tourism and Waste Management Issues

Popular pilgrimage sites and trekking routes attract large numbers of tourists, often in short seasons. Without adequate waste management, water treatment, and visitor caps, fragile alpine ecosystems suffer from litter, sewage contamination, and pressure on local resources. Responsible tourism policies are essential to balance livelihoods with ecological health.

5. Seismic Risk and Geological Hazards

The Himalayan region is highly seismically active due to ongoing tectonic plate convergence. Earthquakes, landslides and slope failures are recurrent hazards. Building codes, hazard zoning, and early warning systems must be rigorously applied and updated to reduce casualty and infrastructure losses.

Conservation Strategies — Practical and Scalable Actions

Addressing these challenges requires multi-pronged strategies that combine science, policy, community engagement, and sustainable economics. Below are effective conservation priorities that can be implemented at local, national, and transboundary levels:

- Climate mitigation & adaptation: Reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote renewable energy, and implement community-level adaptation plans (water harvesting, diversified crops, and climate-resilient infrastructure).

- Glacier and watershed monitoring: Invest in scientific monitoring networks for glaciers, glacial lakes, river flows, and groundwater to inform early warnings and long-term water planning.

- Responsible infrastructure planning: Enforce rigorous environmental impact assessments, adopt slope-stabilizing engineering practices, and limit development in high-risk zones.

- Sustainable tourism: Implement visitor limits, waste management policies, eco-certification for lodges and guides, and tourism revenue-sharing with local communities.

- Forest and habitat restoration: Promote native species reforestation, community forestry programs, and protection of critical wildlife corridors to maintain biodiversity and watershed health.

- Livelihood diversification: Support alternative livelihoods—eco-tourism, value-added agroforestry products, and sustainable harvesting of medicinal plants—to reduce pressure on natural resources.

- Disaster risk reduction: Strengthen early-warning systems for floods and landslides, retrofit critical infrastructure, and conduct community preparedness and evacuation planning.

- Transboundary cooperation: Rivers, glaciers, and ecosystems cross national borders. Regional collaboration on data sharing, river basin management, and conservation financing is essential.

Role of Local Communities and Indigenous Knowledge

Local and indigenous communities are custodians of mountain landscapes. Their traditional knowledge—about medicinal plants, seasonal patterns, water management and sustainable grazing—must be integrated into conservation strategies. Empowering communities with legal rights, capacity building and fair benefit-sharing strengthens both conservation outcomes and local resilience.

Individual Actions — What You Can Do

Individuals can contribute meaningfully by choosing low-impact travel practices, reducing plastic use, supporting local conservation initiatives, and advocating for stronger climate policies. Simple acts—like carrying reusable water bottles, following designated trails, and respecting local rules—help keep mountain ecosystems healthy.

Conclusion — A Collective Responsibility

The Himalayas are an irreplaceable natural, cultural and hydrological asset. Protecting them requires urgent, sustained and inclusive action across sectors and borders. By combining science, policy, local leadership and responsible behavior, we can reduce risks and steward the Himalayas so that their waters, wildlife, and cultures endure for generations to come.

|

Product Name HereAdd a short description here — key features or product highlights. |

| Buy on Amazon |

Personal Story — A Community-led Himalayan Revival

A few years ago I spent three months living in a small Himalayan village called Tharling (name changed) to study community responses to changing water patterns. The hamlet sat on a steep slope above a narrow river valley, its terraces carved by generations of farmers. At first glance the place felt timeless — stone houses, prayer flags, and narrow paths — but conversations revealed a different story: springs were drying, planting seasons were shifting, and many young people were leaving for towns in search of work.

My aim was simple: listen first, then work with the locals to design practical, low-cost solutions. I joined the villagers in field visits, tea gatherings, and school meetings. The elders mapped historical water sources from memory; women described when medicinal herbs used to be plentiful; children drew maps of landslide-prone slopes. These human memories became the baseline for our small project.

Actions Taken — Practical, Community-driven Steps

Together we launched three complementary initiatives. First, we built a series of small, hand-dug recharge ponds on upper slopes to capture monsoon runoff and raise the groundwater table. Second, we started a community nursery for native trees and medicinal plants, managed and protected by a rotating local committee. Third, we organized ‘eco-skills’ sessions: basic waste management, low-impact tourism training, and simple slope-stabilization techniques that farmers could apply themselves.

These interventions were intentionally low-tech and low-cost. Materials were locally sourced, labor was communal, and decision-making remained in the hands of villagers. External funding covered only tools and a modest stipend for a local coordinator; technical advice was provided through short visits by a geologist and a forestry student.

Outcomes — Small Steps, Visible Impact

Within a year the effects were visible. The recharge ponds held water through the dry season and two springs that had weakened began flowing more steadily. Farmers experimented with drought-tolerant crops and reported improved yields in marginal plots. The nursery supplied saplings for terrace buffers and native hedges that reduced soil erosion. Importantly, young people found part-time work guiding weekend eco-visits and producing handmade herbal products, which reduced seasonal migration slightly.

The deeper lesson was social rather than technical: when people feel ownership, maintenance continues and benefits last. The project showed that combining traditional knowledge with simple, scalable interventions can increase ecological resilience and livelihoods in sensitive mountain environments.

If you plan a Himalayan project, start by listening, prioritize local leadership, and favor solutions that communities can sustain without long-term external dependency. Real change in the mountains often begins with small, steady steps — and the willingness to work together.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How were the Himalayas formed?

The Himalayas were formed around 50 million years ago when the Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate. This massive continental collision caused the Earth's crust to fold, rise, and create a chain of towering mountains. Since both plates are light and buoyant, neither could sink beneath the other, resulting in the uplift of land instead. This ongoing tectonic activity continues today, which is why the Himalayas are still rising by a few millimeters every year. Scientists refer to them as a “young mountain range,” reflecting their dynamic and evolving nature.

2. Why are Himalayan glaciers important for Asia?

Himalayan glaciers act as Asia’s primary freshwater reservoirs. They feed major rivers such as the Ganges, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, and Indus, supporting agriculture, drinking water, hydropower, and biodiversity across several countries. During summer, glacier melt ensures a constant water supply even when rainfall is low. However, rapid melting due to climate change threatens long-term water security, raising concerns about droughts, floods, and ecological disruption. Protecting these glaciers is crucial for maintaining stable river systems and safeguarding communities dependent on them.

3. What types of wildlife are found in the Himalayas?

The Himalayas host a rich variety of wildlife, thanks to their diverse climate zones and altitude gradients. Iconic species include the snow leopard, red panda, Himalayan black bear, musk deer, and Himalayan monal. Many species are endangered, primarily due to habitat loss and climate change. The region also supports thousands of medicinal plants and unique flowering species that thrive at different elevations. This biodiversity makes the Himalayas one of the most important ecological hotspots in the world, requiring careful protection and sustainable management.

4. What major challenges are facing the Himalayan region today?

The Himalayas face multiple challenges, including rapid glacier retreat, climate change, deforestation, unplanned urbanization, and increasing tourism pressure. Fragile slopes are vulnerable to landslides, while seismic activity poses additional risks. Pollution from plastic waste, vehicle emissions, and poorly managed construction further degrades the environment. These challenges threaten not only the ecological health of the region but also the cultural heritage and livelihoods of millions who depend on Himalayan resources. Immediate and long-term conservation efforts are essential to address these growing threats.

5. How can individuals contribute to protecting the Himalayas?

Individuals can help protect the Himalayas by practicing responsible tourism, avoiding plastic waste, supporting local communities, and respecting environmental guidelines during travel. Small lifestyle choices—such as conserving water and energy, reducing carbon emissions, and choosing sustainable products—also make a meaningful impact. Participating in reforestation drives, promoting awareness, and supporting conservation organizations further strengthens protection efforts. When many people take small, conscious steps, the collective impact becomes powerful enough to help preserve the Himalayan ecosystem for future generations.

References

- Geological Survey of India (GSI): Detailed reports on the origin, tectonics, rock types, and geological evolution of the Himalayas.

- Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change (Government of India): Official documents on climate change impacts, glacier studies, and conservation policies related to the Himalayan region.

- National Mission on Himalayan Studies (NMHS): Research papers covering Himalayan biodiversity, ecosystems, and sustainable development practices.

- UNEP & UNESCO: Global studies on Himalayan ecology, water resources, mountain environments, and climate vulnerability.

- ICIMOD (International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development): Comprehensive reports on Himalayan glaciers, river systems, regional climate trends, and community-based conservation.

- Peer-reviewed Geological Research Papers: Scientific articles explaining plate tectonics, mountain formation, and the uplift history of the Himalayas.

- Books and Historical Records on Himalayan Culture: Sources covering Himalayan civilizations, folklore, pilgrimage traditions, and socio-cultural heritage.

These references provide credible scientific, cultural, and environmental insights into the Himalayas. Using reliable sources ensures accuracy, depth, and authenticity in research and academic writing.