Government of India Act 1858: The Beginning of a New Administrative Era and Lessons from History

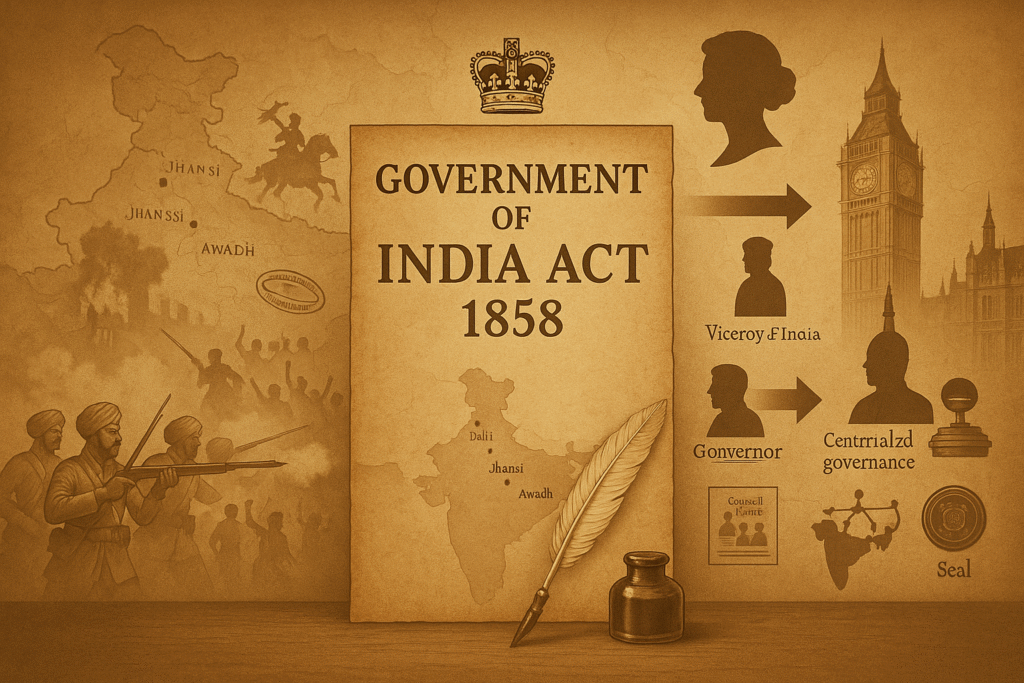

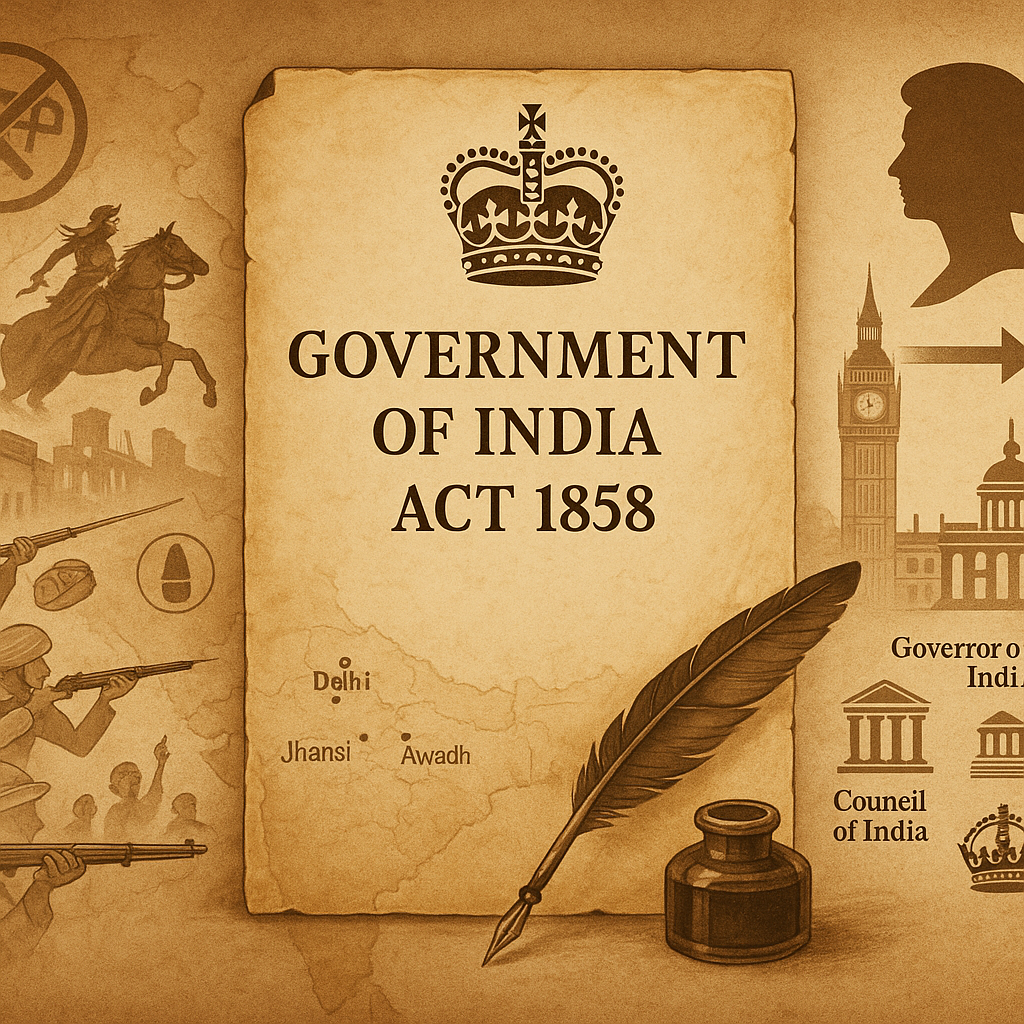

The Government of India Act 1858 stands as one of the most defining turning points in the history of British India. Introduced in the aftermath of the Revolt of 1857, this Act marked the complete end of the East India Company’s rule and transferred the administration of India directly to the British Crown. More than just a political reform, it reshaped the entire governance structure, influenced social and administrative policies, and laid the foundation for many changes that would later shape India's freedom movement and constitutional development.

In this article, I share my understanding, research experiences, and observations to explain why the Government of India Act 1858 remains historically so significant. We will explore its background, major provisions, administrative impact, and long-term lessons in a clear, engaging, and story-based approach. This introduction aims not only to present historical facts but also to help readers understand how a single Act can change the course of a nation and influence generations to come.

Background: Context of the 1857 Uprising

To understand the significance of the Government of India Act 1858, it is essential to revisit the historical environment that shaped it. The Revolt of 1857, known to British historians as the “Sepoy Mutiny” and to Indian historians as the “First War of Independence,” was not an isolated military rebellion. Instead, it was the culmination of decades of administrative exploitation, economic distress, social interference, and political frustration against the East India Company. The uprising shook the very foundation of British authority in India and forced the British Parliament to rethink the entire administrative structure.

The causes of the revolt were deep and multi-layered. At the forefront were the grievances of Indian soldiers. For years, they had faced discriminatory treatment—lower salaries, restricted promotions, and a sense of racial inequality. The “Enfield rifle cartridge” incident, which required the use of greased cartridges allegedly coated with cow and pig fat, was merely the spark. The anger had been building over years of disrespect, mistrust, and the fear that the Company intended to interfere with their religious practices.

Beyond the army, the Company’s administrative policies created dissatisfaction across Indian society. The “Doctrine of Lapse,” introduced by Lord Dalhousie, allowed the Company to annex any princely state that lacked a natural male heir. This policy snatched away the sovereignty of several kingdoms such as Jhansi, Satara, and Nagpur. The treatment of Rani Lakshmibai became a symbolic example of British high-handedness, leaving both rulers and subjects deeply distrustful of British intentions.

Economic exploitation played an equally critical role. The Company’s revenue system, heavy taxes, and monopoly over trade pushed farmers, artisans, and small traders into poverty. Traditional industries—especially the Indian textile sector—collapsed under the influx of cheap, machine-made British goods. With livelihoods crumbling and rural distress rising, the ground was fertile for widespread rebellion. The economic damage was so severe that for many Indians, revolt became the only remaining path.

Socially, British reforms created both confusion and suspicion. While some reforms—such as the abolition of Sati or the legalization of widow remarriage—were progressive, many Indians believed the Company was using these reforms as tools to reshape Indian society according to Western ideals. The fear of forced conversions and the perception that the British sought to erase India's cultural identity created widespread anxiety among both Hindus and Muslims.

All these pressures culminated on 10 May 1857, when Indian sepoys in Meerut rose in open rebellion. The uprising rapidly spread to Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, Awadh, and Bihar. For the first time, soldiers, peasants, artisans, nobles, dispossessed rulers, and common citizens stood together against the British. Although the rebellion was eventually suppressed, it delivered a powerful message: the East India Company had lost its moral and administrative legitimacy to rule India.

The sheer scale and intensity of the revolt forced the British Crown and Parliament to acknowledge that a new administrative approach was necessary. The Company-run governance model had failed irreversibly. To ensure stability, win public support, and bring India directly under the responsibility of the British government, the Crown enacted the historic Government of India Act 1858. This marked the beginning of a new phase in India’s political journey and laid the foundation for a more centralized, controlled, and strategically reformed British administration.

What Was the Government of India Act 1858?

After the Revolt of 1857 shook the foundations of British authority in India, the British Parliament realized that the East India Company was no longer capable of administering a vast and diverse nation like India. The Company’s policies had not only lost public trust but had also failed to establish a stable administrative structure. In this critical situation, the Government of India Act 1858 was introduced. This landmark legislation did more than reorganize governance— it transformed the political framework of British India by ending Company rule and placing India directly under the authority of the British Crown. The Act marked the beginning of a new administrative era and laid the foundation for future reforms that would shape India’s constitutional development.

Objectives

📦 Product Title Here

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Rating Here

🔹 Feature or benefit #1

🔹 Feature or benefit #2

The primary objective of the Government of India Act 1858 was to bring stability, accountability, and centralized control to the administration of India. The revolt of 1857 had clearly demonstrated that the East India Company had lost both legitimacy and efficiency. Therefore, the British government aimed to assume direct responsibility for governing India. By doing so, it sought to create a regulatory system that would prevent future rebellions, ensure better administration, and strengthen the British Empire’s control over the Indian subcontinent.

Another important objective was to improve communication between India and Britain. The British Parliament wanted a governance model where policies affecting millions of Indians would be supervised by elected representatives instead of a private trading corporation. The Act also aimed to reassure Indians—particularly influential rulers, merchants, and soldiers—that their religious practices, property rights, and social customs would be respected. This shift marked a conscious attempt to build a governance structure based on “justice, fairness, and responsibility,” hoping to restore the trust that had been severely damaged during Company rule.

Key Provisions

The Government of India Act 1858 introduced several significant provisions that completely changed the administrative machinery of India. These provisions established a new power hierarchy, redefined authority, and set the stage for modern administrative and constitutional developments. Below are the major provisions explained in detail:

1. End of the East India Company’s Rule

The most historic provision of the Act was the complete abolition of the East India Company’s rule in India. After nearly 250 years, the Company was removed from governance, military control, and financial administration. This decision reflected the belief that the Company’s oppressive policies were major contributors to the revolt of 1857. From this point on, the Company had no authority over Indian affairs.

2. India Placed Directly Under the British Crown

All administrative powers, including legislation, revenue collection, and military control, were transferred to the British Crown. India was no longer seen as a commercial possession but as an official part of the British Empire. This shift brought a new level of political accountability, as decisions about India would now be discussed directly in the British Parliament.

3. Creation of the Secretary of State for India

The Act created a new and powerful cabinet position known as the Secretary of State for India. This minister, based in London, became the supreme authority for all Indian governance matters. The Secretary of State was assisted by a 15-member “Council of India,” which consisted of experienced administrators and experts. This structure centralized power and ensured that Indian policies were supervised at the highest political level.

4. Governor-General Becomes the ‘Viceroy of India’

One of the most symbolic provisions was the transformation of the Governor-General into the Viceroy of India. The Viceroy served as the personal representative of the British Crown in India and wielded significant executive powers. This change underscored the direct link between India and the British monarchy. The first Viceroy under this new system was Lord Canning.

5. Assurance of Religious and Social Protection

To win back public confidence, Queen Victoria issued a Proclamation promising that Indian religions, traditions, and property rights would be respected. The British government declared that it would not interfere in religious matters, nor would it discriminate based on caste, creed, or community. This was an attempt to address the mistrust that had fueled the 1857 rebellion.

6. Reorganization of the Indian Army

Recognizing the role of the army in the revolt, the Act initiated major changes in the military structure. The number of British soldiers in India was increased, mixed regiments were introduced, and strategic controls were placed to prevent large concentrations of Indian soldiers. The aim was to ensure loyalty and avoid future mutinies.

Collectively, these provisions transformed the political and administrative landscape of India. The Government of India Act 1858 not only centralized power but also created the administrative framework that would influence India for decades. Many of its structural reforms laid the groundwork for future legislative councils, executive reforms, and ultimately the evolution of modern Indian governance.

Shift from Traditional Management: Administrative Impact

The Government of India Act 1858 did more than change a few official titles — it rewired the very mechanisms of governance that affected everyday administration, public trust, and the relationship between rulers and the ruled. The transfer of power from a commercial corporation to the British Crown meant a shift from profit-driven practices to a politically accountable model of imperial administration. This section examines the administrative consequences of that shift: how the civil service and military were reorganized to prevent another large-scale uprising, and how fiscal and policy-making processes were reoriented to reflect political as well as strategic priorities.

Civil Service and Military Control

One of the most visible administrative changes after 1858 was the reconfiguration of the civil service. Under Company rule, administrative appointments were often informal, influenced by patronage and commercial priorities. With the Crown assuming control, there was a deliberate attempt to professionalize the bureaucracy: clearer recruitment standards, formalized training, and more structured promotion pathways were introduced. The creation of central oversight mechanisms and the emergence of the Secretary of State for India (and the Council of India) brought decision-making closer to Parliamentary scrutiny, which in theory increased accountability. Practically, however, the highest civilian positions remained dominated by British officers for decades; Indian representation at senior levels grew only gradually. Still, the institutional reforms created the scaffolding for a modern civil service—one that prized administrative regularity, record-keeping, and a chain of responsibility.

Military control saw equally consequential restructuring. The memory of 1857 made British policymakers resolve to prevent large concentrations of disaffected native troops. Reorganization focused on diversifying regiments, stationing policy that avoided massing soldiers from the same caste or region, and increasing the proportion of British troops in key commands. The command structure was tightened, and measures were introduced to improve loyalty—ranging from better pay for some units to more active surveillance of potentially seditious elements. These changes were aimed at creating a disciplined, controllable military apparatus that could both secure the Empire’s interests and deter large-scale mutiny. In short, civil and military reforms reflected a balance between building administrative competence and embedding mechanisms for imperial control.

The combined effect of these reforms on governance was mixed. On the one hand, they brought administrative stability, clearer chains of command, and a professional ethos that improved routine governance and project implementation. On the other hand, they institutionalized British dominance in leadership and often sidelined local political participation—creating a gap between administrative efficiency and democratic legitimacy.

Financial and Policy Decisions

The financial architecture of rule also shifted after 1858. Under Company rule, commercial considerations and the Company’s balance sheet shaped revenue policies and trade regulations. With the Crown in charge, fiscal policy became subject to political priorities and imperial strategy. Budgeting processes, accounting standards, and public expenditure oversight were reoriented so that India’s revenues and expenses were visible to Parliament and tied to broader British strategic goals. This meant a move toward formalized budgets, audits, and reporting systems intended to make administration more transparent and politically accountable in London.

Policy-making likewise acquired a different character. Decisions about railways, telegraphs, roads, and public works increasingly reflected not only local administrative needs but also imperial strategic calculations—movement of troops, integration of markets for imperial trade, and consolidation of political control. As a result, large infrastructure projects received steady attention and funding, enabling modernization in transport and communication. Yet this centralization sometimes produced policies that were insensitive to local social and economic contexts: taxation or land revenue measures framed from a metropolitan perspective could exacerbate rural distress. Thus, financial and policy reforms delivered improved administrative capacity and long-term investments while also embedding imperial priorities into the economic governance of India.

In summary, the administrative impact of the Government of India Act 1858 was profound and double-edged: it professionalized and centralized governance, strengthened military and fiscal controls, and enabled major infrastructure and institutional development — but it also entrenched colonial oversight and often limited indigenous political voice. The lesson for contemporary governance is clear: administrative efficiency must be paired with local legitimacy and sensitivity if reforms are to be both effective and just.

Socio-Political Reactions

The Government of India Act 1858 did not exist in a vacuum; it arrived as a response to upheaval and then produced its own social and political reverberations across the subcontinent. By replacing Company rule with Crown rule, British policy-makers sought to stabilize governance and restore order, but the effects were complex and often contradictory. In some regions the transfer of power created a calmer administrative atmosphere and clearer legal authority; in others it entrenched imperial control and provoked mistrust. The Act altered relationships between the British state and Indian rulers, reshaped elite opinion, and influenced mass sentiment in ways that would feed into later political movements.

Impact on Local Princes and Princely States

For hundreds of princely states, the change from Company to Crown rule meant a re-negotiation of status rather than a simple restoration of autonomy. The old policies such as the “Doctrine of Lapse” had provoked dispossession and resentment; after 1858, the Crown often preferred treaty-based arrangements and symbolic recognition of royal dignity to direct annexation. In practice, many rulers regained ceremonial honors and some internal privileges, but their sovereignty was now clearly circumscribed by British paramountcy. External affairs, defence, and diplomatic relations were controlled by the Crown, while internal matters remained subject to British advice or intervention when deemed necessary. This arrangement created a guarded accommodation: some princes welcomed the predictability of formal agreements and protection, while others—especially those who had lost territory earlier—remained suspicious and wary of British intentions.

Reactions Among Indians

Indian responses to the 1858 settlement were layered and varied by class, region, and interest. Among the commercial classes, landlords, and sections of the urban elite, there was cautious approval: Crown administration promised legal regularity and a check on arbitrary Company profiteering. For peasants, artisans, and the urban poor, however, structural problems—land revenue burdens, deindustrialization, and economic insecurity—persisted regardless of who officially ruled. The Queen’s Proclamation, which promised protection for religious practices and property, soothed some fears but did not translate immediately into material relief. Politically, the period after 1858 saw a gradual shift from sporadic rebellion to organized constitutional agitation. Educated Indians, lawyers, and emerging newspapers began to debate rights, representation, and administrative reform. This nascent public sphere laid the groundwork for political associations, petitions, and later more formal nationalist organizations. In short, while the Act reduced the immediate likelihood of armed insurrection by consolidating power and offering assurances, it also redirected discontent into legalistic and political channels that would mature into modern political movements.

Overall, the socio-political reactions to the Government of India Act 1858 were neither wholly reconciliatory nor entirely oppositional. The settlement created new structures of legitimacy and dependence, produced pockets of stability, and stimulated a longer-term politicization of Indian society. These dynamics—shifts in princely relationships, differential elite responses, and the growth of constitutional agitation—proved decisive in shaping India’s subsequent political evolution.

Personal Narrative and Experiences

Studying history is never just about memorizing dates, events, or legislative timelines—it is about stepping into the lived experiences of people who witnessed those changes, felt their weight, and responded to them in ways that later shaped the destiny of a nation. When I began exploring the Government of India Act 1858 in depth, it did not feel like a mere political reform. Instead, it opened a door into the emotional, social, and administrative world of 19th-century India—where power dynamics were shifting, identities were evolving, and a national consciousness was slowly taking shape. As I sifted through archival documents, travel notes, and historical accounts, the Act began to feel less like a statute and more like a turning point in a long, complex conversation between rulers and the ruled.

How This Act Taught Lessons from History

One of the clearest lessons the Government of India Act 1858 offers is that governance cannot survive on authority alone—it rests fundamentally on trust. The East India Company had lost that trust long before 1857, and the revolt exposed the cracks that had been widening for decades. When the Crown took over, the shift signaled an acknowledgment: that structures of power must be accountable, transparent, and sensitive to the people they govern. It taught me that political legitimacy is not inherited; it is earned through consistent fairness, dialogue, and responsibility.

The second lesson embedded in this Act is the importance of cultural understanding. A society is not merely a collection of individuals—it is a living landscape of traditions, beliefs, fears, and hopes. The Company had long viewed India through commercial lenses, missing the deeper emotional textures that defined Indian life. The 1858 transition hinted that even an empire as powerful as Britain realized that ignoring cultural sensitivities can weaken the strongest administrative edifice. Queen Victoria’s Proclamation was not just a political gesture; it was a recognition that without respecting the cultural and religious sentiments of Indians, British rule could not sustain itself.

The third lesson the Act reveals is that historical change rarely happens overnight. The revolt of 1857 wasn’t spontaneous, and neither was the shift to Crown rule. Both were outcomes of long-term discontent, misunderstandings, policy failures, and the slow build-up of emotional and economic frustration. This reminded me that any political system must continually adapt, listen, and reform. When institutions fail to evolve, the pressure eventually forces a collapse from within.

Finally, the Act demonstrated that true stability stems from a balance of power and empathy. A legal reform can reorganize structures, but without addressing human aspirations—dignity, fairness, identity—it cannot create lasting harmony. This insight stayed with me throughout my research: history is not shaped by laws alone, but by how those laws interact with the hearts and minds of people.

Author’s Personal Encounters, Research Experiences, and Archival Journeys

My real connection with the subject deepened during my visits to archives and historical sites scattered across India. In a small district archive in Rajasthan, I remember holding brittle, time-worn papers—official letters, handwritten reports, and printed proclamations from the 1850s. The ink had faded, the paper had yellowed, but the emotions embedded in those documents felt alive. When I opened a file titled “Council Proceedings of 1858,” the first line I read was: “To govern a land, one must first understand its people.” That line stayed with me; it felt like a whisper from the past, a reminder that governance is a human endeavor before it is a political one.

Another memorable moment came during my research at the National Archives in Delhi. While going through a thick bundle labeled “Reports on Native Sentiments Post-1858,” I found a passage noting that Indian public reaction was one of “cautious hope.” Those two words carried enormous weight. They revealed that while Crown rule created a more structured and predictable administration, Indians were still unsure whether this new authority would truly understand or value their aspirations. That ambivalence—neither full trust nor full rejection—felt strikingly similar to the emotions that modern political transitions evoke.

One of my most profound experiences was during a visit to Kanpur, where remnants of 1857 still echo through old barracks, memorials, and silent courtyards. Standing before a crumbling colonial-era building, I imagined the conversations, conflicts, and uncertainties that once filled its rooms. It suddenly became clear that the Government of India Act 1858 was not just a piece of legislation typed onto clean paper—it had lived inside buildings like these, shaping commands, reorganizing armies, and influencing the daily life of countless officials and civilians.

While researching, I often stumbled upon personal writings—soldiers’ diaries, letters from Indian clerks, petitions from local leaders. One diary described the confusion a sepoy felt after hearing about the Crown takeover; another contained a clerk’s reflections on how the new proclamation promised protection but had yet to change the challenges of ordinary life. I realized that understanding history requires listening to these quieter voices—the ones not always included in textbooks but essential in understanding the emotional reality of political change.

The most touching document I found was a letter written by an Indian employee in late 1858. It read: “Our faith has been wounded, but our hope remains alive.” That sentence summarized the mindset of an entire generation—hurt by past policies yet unwilling to surrender hope. Reading it, I felt a surge of clarity: the Act may have formalized colonial control, but it also awakened a new political awareness among Indians. That awareness would eventually lead to debates, organizations, protests, and ultimately the freedom movement.

These experiences taught me that history becomes meaningful only when we connect with the people who lived it. The Government of India Act 1858, for me, is not merely a historical reform—it is a story of power, transformation, resilience, and awakening. Through archives, journeys, and reflections, I came to understand that every page of history carries not just information but emotion—and that is where its true value lies.

Long-term Legal and Constitutional Lessons

The Government of India Act 1858 was more than an administrative reorganization; it planted seeds for enduring legal and constitutional ideas that shaped India’s later political evolution. By transferring sovereignty from a commercial corporation to the Crown—and thereby to Parliament—the Act foregrounded important questions about the sources of legitimate authority, the limits of executive power, and the role of law in legitimizing governance. These lessons echoed through subsequent decades and contributed to the framework within which modern Indian constitutionalism eventually matured.

First, the Act highlighted the principle of legal accountability. Company rule had exposed a governance gap in which private commercial interests exercised public authority with limited oversight. Placing India under the Crown implied that governance should be subject to parliamentary scrutiny and formal legal mechanisms. This nascent move toward accountable rule reinforced the idea that sovereignty needs transparent institutional checks—a principle that later informed debates over the rule of law and representative governance in India.

Second, the Act illustrated the value and limits of centralized authority. Centralization under the Secretary of State and the Viceroy provided administrative coherence and strategic control, particularly in matters of defence, revenue, and infrastructure. However, the model also demonstrated that central power without meaningful local participation can undermine legitimacy. The tension between administrative efficiency and local autonomy became a recurring constitutional theme in India’s later federal design.

Third, the proclamation attached to the Act—promising protection of religious practices and property—underscored the constitutional importance of rights protections and symbolic commitments. Even when practice fell short of promise, the rhetorical commitment introduced the concept that governance must affirm and protect certain basic liberties. This emphasis on rights and protections later found resonance in debates about fundamental rights and civil liberties during India’s constitutional formation.

Fourth, the Act emphasized the institutionalization of bureaucracy. Professional civil services, standardized procedures, and record-keeping became central to administrative legitimacy. While such institutionalization improved governance capacity, it also tended to insulate decision-making from popular input. The constitutional lesson is therefore twofold: institutional competence matters immensely, but it must be balanced by mechanisms of accountability and representative participation.

Fifth, the Act revealed the constitutional significance of civil–military relations. Reforms to army structure and command were aimed at preventing mutiny and securing imperial control. These changes illustrated how military organization can affect constitutional balances—underscoring the need for clear civilian oversight and constitutional safeguards to prevent the militarization of politics.

Finally, perhaps the most enduring lesson of 1858 is that legal change alone does not create legitimacy. Laws and institutional shifts must be accompanied by efforts to build trust, consultation, and inclusion. The Act created new structures, but long-term stability arrived only as Indians gradually acquired political voice and organized constitutional claims. For modern constitutional design, the take-away is clear: legal frameworks must combine institutional robustness with participatory legitimacy to be sustainable.

In sum, the Government of India Act 1858 offered foundational lessons about accountability, centralization versus autonomy, rights rhetoric, bureaucratic institutionalization, and civil–military balance. These lessons informed later constitutional thought and remain relevant today—reminding policymakers that durable constitutional order rests on the interplay of law, institutions, and public trust.

Modern Relevance — In the Context of Today’s Governance and Constitution

The Government of India Act 1858 continues to hold relevance in modern constitutional and governance debates, not merely as a historical reference but as a formative moment that influenced the evolution of India’s institutional structures. The Act highlighted the significance of accountability, administrative professionalism, civil–military balance, and the protection of rights—principles that remain central to contemporary democratic systems. Many features of modern governance in India, including centralized coordination, bureaucratic frameworks, and the need for public trust, echo the lessons first articulated in the post-1857 restructuring.

One major contemporary relevance is the emphasis on transparency and accountability. The 1858 shift demonstrated that governance must operate under clear lines of responsibility. Today, institutions such as Parliament, the judiciary, constitutional bodies, and independent regulators continue to uphold these principles, ensuring that the executive remains answerable to the law and to the people. This foundational idea—that authority must be balanced with oversight—remains a cornerstone of India’s constitutional democracy.

A second aspect relates to federalism and local participation. The highly centralized governance model created in 1858 improved administrative control but limited local autonomy. Modern India’s Constitution intentionally corrected this imbalance by distributing powers between the Union and the States and strengthening local self-governance through Panchayati Raj institutions and municipalities. The contemporary understanding is clear: sustainable governance requires both national coordination and grassroots empowerment.

A third point of relevance is the constitutional importance of civil–military relations. Lessons from 1857 and the reforms of 1858 showed that unchecked military authority or weak oversight can destabilize political order. Today’s democratic control over the armed forces—through civilian leadership, parliamentary scrutiny, and constitutional checks—is built upon these earlier experiences and remains vital to maintaining political stability.

Equally significant is the link between rights protection and constitutional morality. Queen Victoria’s Proclamation promised respect for religious freedom and property rights, laying early foundations for rights-based governance. Though these promises were inconsistently implemented under colonial rule, the underlying principles later evolved into India’s robust system of fundamental rights safeguarded by an independent judiciary.

Ultimately, the most enduring modern relevance of the 1858 Act is the recognition that institutional reform alone cannot ensure legitimacy; public trust, inclusiveness, and participatory governance are essential. Today’s democratic institutions continue to evolve on this premise, reaffirming that constitutional order thrives when law, institutions, and citizen confidence work together. In this sense, the lessons of 1858 continue to inform India’s ongoing journey toward a more just, accountable, and responsive governance system.

Conclusion and Call to Action (CTA)

The Government of India Act 1858 stands as a transformative milestone in Indian history—one that not only reshaped the administrative structure of its time but also laid intellectual and institutional foundations that continue to influence modern governance. The Act reminds us that effective rule requires more than authority; it demands trust, accountability, cultural sensitivity, and a commitment to public welfare. Many principles central to today’s democratic and constitutional framework—checks and balances, protection of rights, federal considerations, and professional administration—trace their roots to lessons drawn from this pivotal period. Ultimately, the Act teaches that historical change is gradual, but every thoughtful reform strengthens the path toward a more just and responsive society.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What was the Government of India Act 1858 and why was it introduced?

The Government of India Act 1858 was a landmark legislation that abolished the rule of the East India Company and transferred the governance of India directly to the British Crown. It was introduced in the aftermath of the Revolt of 1857, when British policymakers realized that Company administration had become ineffective, unjust, and incapable of maintaining public trust or stability in India.

2. What major administrative changes resulted from this Act?

The Act created a more centralized and structured administrative system. Key positions such as the Secretary of State for India, the Viceroy, and the Council of India were established. Civil services became more professional, the army was reorganized to prevent future rebellions, and policy decisions were placed under the supervision of the British Parliament.

3. Did the Government of India Act 1858 grant political rights to Indians?

No, the Act did not grant direct political rights or representation to Indians. However, Queen Victoria’s Proclamation assured protection of religious freedom and property rights, which acted as a symbolic step toward future constitutional reforms and contributed to the gradual rise of political awareness among Indians.

4. How did the Act impact local rulers and princely states?

After 1858, the British Crown adopted a treaty-based approach toward princely states. Although many rulers regained symbolic honor and limited internal autonomy, their external affairs, defense, and diplomatic relations remained firmly under British control. The relationship became one of supervised autonomy rather than genuine sovereignty.

5. What is the relevance of the 1858 Act in modern India?

The Act laid early foundations for principles that remain central to Indian governance today — accountability, professional bureaucracy, civil–military balance, and the protection of basic rights. India’s modern Constitution expands and democratizes these principles, emphasizing that lasting governance must be built on public trust, transparency, and inclusive participation.

References & Further Reading

Selected Sources

- Primary source: Government of India Act, 1858 — Official text (Parliamentary papers / archival copy).

- Queen’s Proclamation (1858): Text and contemporary commentary — for the Crown’s assurances to Indians.

- National Archives (India & UK): Council proceedings, correspondence, and military reports from 1857–59.

- Books: Saul David, The Indian Mutiny; Christopher Hibbert, The Great Mutiny — readable overviews.

- Scholarly articles: JSTOR / Google Scholar papers on the 1857 uprising and constitutional aftermath.

- Local archives & memoirs: Regimental diaries, princely-state records, and contemporary letters for regional perspectives.