Introduction — My First Memory and the Deep Impact of the Ganga

I still remember the morning as if it were painted in slow motion: dawn breaking over Varanasi, saffron light spilling across the ghats, and the river breathing a soft, rhythmic sigh. I was a child then, perched on a worn stone step, watching priests light lamps and boatmen push off into the mist. That single moment crystallized into a lifelong feeling — the Ganga was not merely a body of water but a living presence that cradled memory, ritual and everyday survival. From that first sensory impression, my interest turned into curiosity, then into study, and finally into a personal commitment to understand what keeps this river alive — and what threatens it.

The Ganga river system is woven into the daily fabric of millions of lives. It supplies water for irrigation that sustains vast agricultural plains, supports fisheries that feed communities, and underpins local economies dependent on pilgrimage and river-based tourism. To put its scale in perspective, the Ganga basin is one of the most densely populated river basins in the world — providing livelihoods directly or indirectly for a very large portion of the Indian population. In many towns and villages along its banks, the river is the primary source of water for drinking, washing and small-scale industry.

Yet the Ganga’s significance extends far beyond economics. It carries centuries of cultural memory: stories, pilgrimages, funerary rites, and festivals that mark life’s milestones. People come to its ghats for solace, to perform rituals passed down through generations, and to connect with a sense of continuity larger than themselves. When I witnessed a family perform a dawn prayer, I felt how river and ritual reinforce identity in ways no policy document can fully capture.

At the same time, my studies and conversations with boatmen, waste collectors, and local farmers revealed an uncomfortable truth: the river that sustains communities is also under pressure from urban growth, untreated sewage, industrial discharge, and single-use plastics. These forces complicate the Ganga’s role as both a sacred symbol and a lifeline. For me, this paradox — reverence alongside degradation — became the central theme of a journey that blends personal stories, scientific insight, and practical solutions.

In this article I will trace the Ganga river system through lived experience and research: describing its geography and ecology, documenting the challenges it faces, and highlighting examples of community-led and policy-driven efforts to restore its vitality. My aim is to offer a narrative that is at once moving and actionable — one that invites readers to feel the river’s pulse and to join in protecting a resource that belongs to all of us.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Origin and Geographical Structure of the Ganga River System

The Ganga is not merely a river—it is a vast and dynamic water system that begins in the icy reaches of the Himalayas and extends all the way to the Bay of Bengal. To understand its full significance, one must look closely at its origin, its major tributaries, and the extensive basin that shapes the lives, landscapes, and economies of millions. My own experiences travelling through the Himalayan foothills and the Gangetic plains helped me realize that the river’s character is a blend of geography, ecology, and human history. What starts as a narrow, powerful stream in the mountains slowly transforms into a wide, fertile, life-sustaining river across the plains.

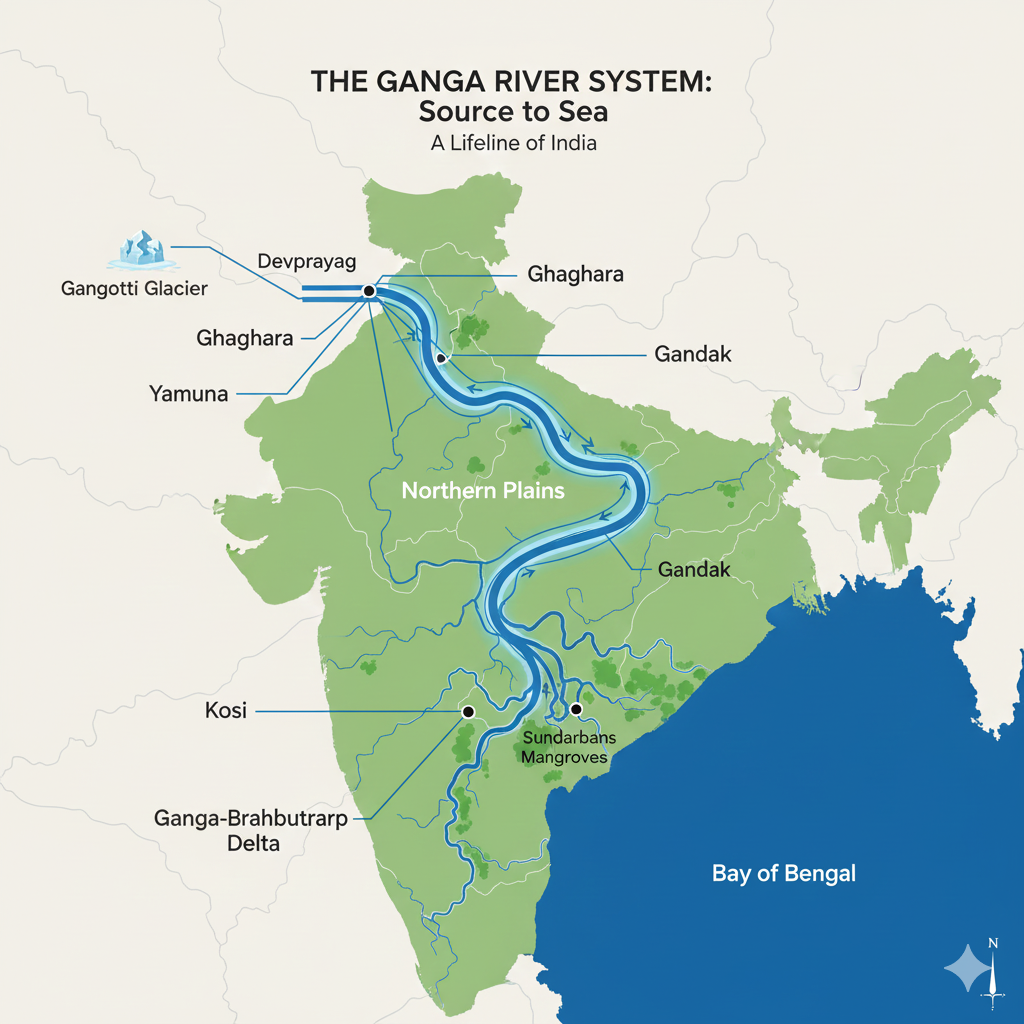

Source and Major Tributaries

The traditional and widely recognized source of the Ganga is the Gangotri Glacier in Uttarakhand, from where the Bhagirathi stream emerges. Scientifically, the river is considered to be formed at the confluence of the Bhagirathi and Alaknanda at Devprayag. The icy terrain of the upper Himalayas gives the Ganga its initial force, clarity, and mineral-rich nature. The journey from Gangotri is dramatic—deep gorges, fast currents, and steep gradients define the river’s early life.

As the Ganga moves downstream, it is joined by several major tributaries that significantly increase its volume, width, and ecological diversity. Among these, the Yamuna is one of the most important. Originating from the Yamunotri Glacier, the Yamuna flows through major urban centers before merging with the Ganga at Prayagraj. This confluence, known as the Triveni Sangam, holds immense cultural, hydrological, and economic importance.

Other major tributaries include the Ghaghara (Saryu), which brings vast Himalayan waters from Nepal; the Gandak, originating near the Tibetan plateau; and the Kosi, a river known as the “Sorrow of Bihar” because of its tendency to shift its course and cause flooding. These tributaries carry not only water but also sediments, biodiversity, and distinct ecological characteristics, contributing to the Ganga’s identity as a complex, interconnected river system. The merging of these tributaries transforms the Ganga from a narrow, swift mountain river into a broad and fertile plains river that supports extensive agriculture.

Basin Extent and Major Regions

The Ganga basin is one of the largest and most densely populated river basins in the world. Its geographic spread covers the towering Himalayan ranges in the north to the vast coastal delta in the south-east. The basin includes major Indian states such as Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal, and extends into Nepal and parts of Bangladesh through interconnected tributary systems.

In the upper Himalayan region, the river flows through steep valleys and narrow channels, characterized by snowmelt-fed streams and rocky terrain. As it enters the Gangetic plains, the river widens considerably, creating expansive floodplains and depositing nutrient-rich alluvium. This fertile soil has made the basin one of the most productive agricultural regions in India. Crops such as wheat, rice, sugarcane, pulses, and oilseeds rely heavily on the irrigation network supported by the Ganga and its tributaries.

The basin also plays a critical role in groundwater recharge. Seasonal floods, although sometimes devastating, help replenish underground aquifers that sustain rural and urban communities throughout the year. The river’s influence extends to climate regulation in the northern plains, shaping rainfall patterns and supporting countless ecosystems along its course.

As the Ganga approaches the eastern regions, it begins forming one of the world’s largest and most dynamic deltas—the Sunderbans Delta. This region, shaped by the combined flows of the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, is home to mangrove forests, rare wildlife, and unique brackish water ecosystems. However, this area also faces severe challenges, including rising sea levels, increased salinity, and erosion—all of which threaten both human settlements and ecological balance.

In essence, the geographical structure of the Ganga river system—from its glacial birth to its vast basin and intricate tributary network—demonstrates how a single river can influence multiple terrains, cultures, and economies. Understanding this geography is essential before exploring the environmental challenges, human interventions, and restoration efforts that shape the river’s future.

Historical and Religious Significance — The Ganga as Timekeeper and Pilgrim

The Ganga’s significance is woven into the very fabric of South Asian history and spirituality. Ancient texts — from the Vedas and Puranas to epics like the Mahabharata — recount the river as a divine gift, a purifier of sins, and a vehicle for salvation. Over centuries, cities and learning centers sprang up along its banks: settlements that became hubs of philosophy, art, law, and commerce. The river was not merely a geographic feature but a civilizational axis around which rituals, social norms, and regional identities formed. Archaeological finds and literary traditions both point to how the river shaped trade routes, agricultural systems and the cultural imagination of millions.

Puranic Stories, Pilgrimages and the Sense of Sacredness — a Personal Reflection

My first encounter with the Ganga’s ritual world was not in a book but on a misty dawn at a small riverside ghat. I remember being startled by a sudden chorus of bells and bhajans as a family performed a ritual for an ancestor. For them, the act was as ordinary as brewing tea — a routine threaded through daily life. It made me realize that the Ganga’s sacredness is not only doctrinal; it is lived, habitual and intimate. The Puranic narratives — of descent (avatarana), of gods and sages bathing in the river, of rituals promising spiritual merit — give intellectual shape to feelings that people on the ground translate into daily practices: offerings, river-front prayers, and life-cycle ceremonies.

Pilgrimage to the Ganga — whether to Haridwar, Varanasi, Prayagraj or lesser-known tirthas — combines devotion with social exchange. Pilgrims carry stories, donations, and skills. Ghats become marketplaces of memory where priests, boatmen, flower-sellers and storytellers sustain each other. These journeys anchor personal biographies to a long chain of communal memory: births, marriages, deaths and the seasonal festivals that mark agricultural and religious calendars. In my conversations with pilgrims, I found that many describe the river as a witness: to joy, sorrow, repentance and hope.

Yet the idea of sacredness coexists uneasily with modern pressures. Urbanization, mass tourism, and the commodification of religious services have altered the texture of pilgrimage. On one hand, wider access has democratized devotion; on the other, it has strained infrastructure and sometimes reduced ritual to a transaction. I have seen small family shrines thrive alongside noisy, commercialized ghats. A pujari once told me, “The river forgives, but the mouth of man does not.” His comment hinted at a deeper truth: the river’s spiritual role cannot be disentangled from the social and environmental context that sustains it.

Historically, rulers and religious institutions have both protected and exploited the river. Royal patronage built ghats, temples and irrigation works; religious networks maintained knowledge and moral authority. This dual legacy gives us an important lesson — any contemporary effort to restore or conserve the Ganga must respect its ritual meanings while applying scientific solutions. Conservation divorced from cultural sensitivity risks alienating local custodians; cultural revival without ecological fixes will be hollow.

Ultimately, the Ganga’s historical and religious layers are not antiquarian curiosities. They are living forces that shape attitudes toward stewardship and responsibility. When people see the river as an ancestor or a living presence, they are more likely to protect it in tangible ways — by campaigning against pollution, participating in clean-ups, or reviving traditional water-management practices. My own takeaway is simple: effective conservation will succeed only when it listens to both scripture and science, hymn and hydrology, memory and management. That integrated approach honors the Ganga’s past while safeguarding its future.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Biodiversity and Ecology — The Natural Heritage of the Ganga

The Ganga is far more than a cultural landmark; it is a living ecosystem that supports an astonishing variety of life along its course — from its Himalayan headwaters to the vast coastal delta. Walking beside the river at different seasons, I noticed how the river’s character changes: fast, clear mountain streams that support cold-water life gradually become slow, sediment-rich plains waters teeming with different species. This transition shapes habitats, seasonal movements, and the livelihoods of people who depend on the river’s natural rhythms.

Fishes, Vegetation and the Delta Ecosystem

Fish diversity is one of the most visible measures of the Ganga’s ecological wealth. The river supports a range of economically and ecologically important species such as Rohu, Catla, Mrigal, the migratory Hilsa (Ilish) in the lower reaches and delta, and prized game fishes like Mahseer in the upper tributaries. These species vary by reach — some spawn in upland tributaries and migrate downstream as juveniles, while others complete their life cycles largely within the plains. Local fishing communities have evolved knowledge systems around these seasonal patterns, and their livelihoods are intricately tied to the health of fish populations.

Riverbank and floodplain vegetation also play crucial roles. In upland areas, coniferous and mixed broadleaf forests moderate stream flows and provide leaf-litter inputs that sustain aquatic food webs. Across the plains, riparian grasses, sedges, and herbaceous plants — along with wetland macrophytes — stabilize banks, trap sediments and provide nursery habitat for juvenile fish and amphibians. Invasive species such as water hyacinth can, however, choke channels and reduce dissolved oxygen, demonstrating how small shifts in plant communities cascade into broader ecological impacts.

The Ganga–Brahmaputra–Meghna delta, including the Sundarbans, represents the river system’s final and most complex ecological expression. The delta is a mosaic of mangrove forests, estuarine channels, mudflats and brackish-water wetlands. Mangroves buffer storm surges, prevent erosion and create rich breeding grounds for fish, crustaceans and migratory birds. The interplay of fresh and saline waters in the delta supports species adapted to variable salinity and fuels local fisheries that underpin coastal economies.

Vulnerable Species and Stories of Conservation

Several species in the Ganga are emblematic of the river’s ecological health and have become focal points for conservation. The Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica) is perhaps the most poignant example — an indicator species whose presence signals relatively clean, continuous flows and healthy fish stocks. Once abundant across many reaches, dolphins now face threats from habitat fragmentation (dams and barrages), pollution, boat traffic and accidental entanglement in fishing gear. In many stretches I visited, local NGOs and youth groups run "dolphin watch" programs that combine monitoring with public education; their work has helped reduce harmful fishing practices and build local pride in conserving this unique mammal.

Freshwater turtles and gharial crocodiles are other vulnerable inhabitants. Community-led hatcheries and rescue centers have become important conservation stories: volunteers protect nesting beaches, incubate eggs when needed, and release hatchlings during the monsoon pulse. These projects often blend scientific guidance with traditional knowledge — for example, coordinating release timing with natural flood cycles to increase survival rates.

The Sundarbans’ mangroves have also been the focus of inspiring local action. Women’s self-help groups and coastal cooperatives have led mangrove restoration and nursery programs. They raise seedlings in community nurseries, plant them along eroding banks and monitor survival. Beyond ecological benefits, these activities generate alternative livelihoods — nursery work, mangrove-based tourism, and sustainable shellfish harvesting — which reduce pressure on wild resources and improve local resilience to storms and sea-level rise.

These conservation stories show a common thread: successful interventions are often local, pragmatic and culturally aware. They combine habitat protection (for instance, safeguarding nesting sites), pollution control, sustainable fishing practices and meaningful community participation. Protecting biodiversity in the Ganga is not an abstract conservation ideal; it is a practical necessity that sustains food security, livelihoods and the river’s capacity to recover and self-purify.

In short, the Ganga’s biodiversity is a living ledger of its health. Preserving the fish, plants and sensitive species that rely on the river requires coordinated policies, scientific monitoring and — crucially — the active stewardship of communities who live by the water. Only by linking ecological science with local knowledge and social incentives can the Ganga continue to be both a cultural symbol and a thriving natural system for generations to come.

Human Interventions: Dams, Canals and Embankments

Human interventions along the Ganga river system have profoundly shaped its physical character, ecological balance and socio-economic role. Over the past century, dams, barrages, canals and embankments have expanded rapidly, driven by the goals of irrigation, flood control, navigation and energy production. During my travels across different stretches of the river, I noticed how these structures create a dual reality: they bring significant benefits to millions, yet they also alter the river’s natural rhythm in ways that are sometimes disruptive. Understanding both sides is essential for designing sustainable water management for the future.

Benefits — Irrigation, Electricity and Regional Development

Some of the most notable advantages of human intervention come from major structures such as the Tehri Dam, Narora Barrage, and Farakka Barrage. These projects have enabled vast irrigation networks across northern India, especially in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Farmers repeatedly told me that canal-fed irrigation has made it possible to cultivate water-intensive crops like rice, wheat and sugarcane. Without these canals, large parts of the Gangetic plains would face frequent drought-like conditions during the pre-monsoon months.

Hydropower is another major gain. The Tehri Dam, for example, generates substantial electricity that supports both households and industries across northern states. Many small towns that once struggled with unreliable electricity now benefit from more consistent power supply, enabling small industries, cold-storage units and rural enterprises to grow.

Embankments have also reduced the immediate threat of seasonal flooding in several densely populated regions. Communities living along low-lying areas told me that embankments protect their homes, markets and farmland from annual monsoon surges that once caused widespread destruction.

Drawbacks — Ecological Changes and Impact on Farmers and Industries

The other side of the story is far more complicated. Dams and barrages fragment the river’s natural flow, reducing its self-purification ability, altering sediment movement and affecting aquatic habitats. Scientists studying the Ganga basin have noted that reduced sediment flow downstream contributes to erosion in the delta, while stagnant stretches upstream of barrages can increase pollution concentration and change water temperature.

For farmers, the canal systems are both a blessing and a burden. While some regions benefit from steady irrigation, others face problems like waterlogging and soil salinity due to excessive or poorly managed canal water. In my interactions with farmers in eastern Uttar Pradesh, many explained that when canals overflow or leak, fields become waterlogged, reducing crop yields. Meanwhile, other villages receive insufficient water despite being geographically close to the canal network — a sign of uneven distribution and weak maintenance.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Industries too experience mixed effects. Continuous access to river water supports sugar mills, textile units and power plants. However, altered flows can disrupt their operations. For instance, in regions where water levels drop because of upstream regulation, industries must invest in additional pumping, treatment and storage systems, raising operational costs. Moreover, regulatory pressure has increased as pollution from industrial units has become a major concern for river health.

Embankments, though helpful in controlling floods, sometimes create new risks. By confining the river to a narrow channel, embankments prevent natural floodplain spread and increase the intensity of water pressure. This can lead to sudden breaches, which often cause far more devastating floods than natural ones. Bihar’s embankment breaches are well-known examples, causing widespread displacement and agricultural loss.

Ultimately, human control over the Ganga river system is a story of trade-offs. Developmental needs — irrigation, energy, navigation and flood protection — have to be balanced with ecological health and the rights of communities dependent on the river. Sustainable management will require more flexible policies, better infrastructure maintenance and stronger collaboration between governments, scientists and local users. Only then can the Ganga continue to support both human progress and natural harmony.

Pollution and Current Challenges — The Ganga’s Toughest Test

The Ganga river system today faces one of its most serious crises: pollution. Rapid urbanization, expanding industry, single-use plastics, mass tourism, and weak waste-management systems combine to stress a river that has supported millions for centuries. During my travels along the river, I witnessed this paradox up close — places of deep reverence and beautiful ritual clogged with visible waste, stretches of once-clear water turned murky, and local communities grappling with health, livelihood and cultural impacts. Understanding the sources and the human stories behind pollution is essential if we want to design workable solutions.

Sources of Pollution — Domestic, Industrial and Plastic Waste (Field story & material examples)

Domestic wastewater is the largest single contributor to pollution in many stretches of the Ganga. In towns and informal settlements along the banks, untreated sewage, greywater from households, and food-waste frequently find their way into drains that empty directly into the river. I remember standing near a small ghat at dawn where laundry, dishwater and toilet effluent flowed through the same open channel into the main stream. Residents explained that decades of population growth had outpaced sewer infrastructure — a problem of planning and resources as much as individual behavior.

Industrial effluents are the second major source and are often more toxic. Leather tanneries, dyeing units, chemical plants and some food-processing units produce wastewater with heavy metals, dyes, high biochemical-oxygen demand (BOD) and toxic residues. In industrial towns, I observed discolored water near discharge points and heard from local activists about fish kills and skin ailments among people who use river water for bathing. Even where treatment plants exist, poor maintenance or illegal bypassing can allow dangerous effluent to escape into the river system.

Plastic pollution has surged as a visible and persistent problem. Devotional offerings wrapped in plastics, single-use bottles, polythene bags and packaging materials clog drains, accumulate along embankments, and float on calmer stretches of the river. I spoke with a group of fishermen who showed me nets torn and fouled by plastic, and told stories of declining catches and extra labor sorting trash from fish. Plastics not only degrade water quality but also harm aquatic life and increase microplastic contamination of the food chain.

Successful Initiatives — Rays of Hope and Scalable Models

Despite the scale of the challenge, several promising interventions are showing results. Large-scale national programs targeting river restoration have helped mobilize funding for sewage treatment plants, riverfront improvement, and pollution monitoring. More importantly, many local, community-driven projects offer instructive models: volunteer clean-up drives that combine public awareness with regular waste removal; decentralized sanitation projects that provide small towns with context-appropriate sewage solutions; and partnerships where industries invest in modern effluent treatment and resource recovery rather than dumping untreated waste.

I visited one riverside town where a simple segregation-and-composting program transformed a crowded ghat. Local volunteers set up plastic collection points, trained flower-sellers to accept returnable or biodegradable packaging, and started a small composting unit that turned floral waste into fertilizer for nearby farms. The change was tangible: cleaner water at the shorelines, healthier fish populations reported by local fishermen, and new income streams from compost sales.

Technological innovations also contribute. Upgrading and properly maintaining sewage treatment plants, promoting decentralized wastewater treatment for peri-urban and rural areas, and adopting industrial cleaner-production processes reduce toxic loads. Additionally, behavior-change campaigns — especially those that work through religious leaders, schools and local women’s groups — can reduce the direct disposal of offerings and single-use plastics into the river.

Ultimately, remedying pollution in the Ganga requires integrated action: robust infrastructure, strict enforcement, transparent monitoring, corporate responsibility, and sustained community engagement. Personal choices—reducing single-use plastics, using community collection points, and supporting local conservation groups—matter as much as policy. The river’s recovery will be incremental, but with coordinated efforts that combine technology, governance and cultural sensitivity, it is possible to restore significant stretches of the Ganga to health and safeguard its role as both a lifeline and a sacred landscape.

Local Communities and Life — People Who Live by the Ganga

The Ganga is more than a watercourse; it is the backdrop to countless human stories. Along its banks, entire ways of life have evolved around seasonal rhythms, riverine resources and ritual occasions. Over repeated visits to towns and villages on different stretches of the river, I observed how the Ganga structures daily routines, economic choices and social relationships. The river supports livelihoods, shapes identities and binds communities through shared practices—yet it also exposes them to environmental and economic vulnerabilities.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Fisherfolk — Livelihoods Tied to the River’s Health

Fishermen and fishing communities are among the most intimate observers of the river’s changing moods. At dawn, small wooden boats dot the surface and nets are cast into eddies where fish congregate. These communities possess detailed generational knowledge—when certain species migrate, where juveniles shelter and which micro-habitats produce reliable catches. I spoke with fishers who described how subtle shifts in flow, water clarity or sediment deposition immediately alter catches and income. Declining fish populations, increasing plastic in nets, and disturbances from motorboats have made livelihoods precarious for many families. Community-managed cooperatives and seasonal rules about gear and timing have helped in some places, but long-term recovery depends on cleaner water and sustainable river management.

Ghat Families and Service Economies

The ghats form a parallel economy: priests, boatmen, flower-and-offering sellers, priests’ assistants, small tea and sweet vendors, laundries, and artisans all earn their living from the river’s flow of people. I watched a single ghat transform over the course of a morning—pilgrims arriving for ritual baths, vendors arranging offerings, boatmen ferrying visitors, and families conducting life-cycle rites. Many ghat-families have inherited roles across generations; their knowledge of ritual timings, local patrons and river etiquette is a social capital that sustains them. However, modernization, regulation, and shifts in pilgrimage patterns sometimes disrupt these traditional economies, forcing families to diversify into tourism services, guiding or small retail.

Festivals, Rituals and Seasonal Incomes

Festivals are high points in the Ganga’s annual cycle, producing surges of both devotion and income. Events like the month-long fairs, daily evening aartis, the seasonal peaks of pilgrimage and regional celebrations such as Chhath or local mela create temporary markets for hospitality, food, transport and religious goods. During these times, informal labor—temporary guesthouse staff, boat guides, stall workers and porters—find their best earning opportunities. I observed how some households plan their year around these peaks, saving festival-season earnings to tide them through lean months. Yet festivals can also strain local infrastructure and generate significant waste, creating new livelihood challenges that require coordinated planning and greener festival practices.

In summary, communities along the Ganga exhibit resilience and resourcefulness. Their survival strategies—cooperatives, waste-collection groups, eco-tourism initiatives and livelihood diversification—offer paths to sustain both culture and income. Protecting the river, therefore, means protecting the social fabric that depends on it: policies and restoration efforts must pair ecological recovery with livelihood support, so that riverside communities can continue to live with dignity beside the Ganga.

Future and Solutions — A Roadmap to Restoring the Ganga

Restoring the Ganga is neither a single tech fix nor a purely sentimental mission; it requires coordinated policy, empowered communities and appropriate technology working together. The river’s recovery demands strategies that are scientifically grounded, socially inclusive and economically viable. Below I outline practical policy directions, community-led approaches and technological opportunities that—when combined—can create a resilient pathway for the river and the people who depend on it.

Policy Recommendations

Clear, enforceable and time-bound policies are the foundation of any large-scale restoration. First, establish river-specific water-quality targets tied to stretches of the basin and enforce them via transparent monitoring systems. Invest in decentralized and centralized sewage treatment capacity so that urban growth does not outpace sanitation infrastructure. Strengthen regulations on industrial effluent with strict penalties for non-compliance, and incentivize cleaner production through tax breaks, green bonds or low-interest loans. Protect floodplains and wetlands through zoning laws that prevent unplanned construction, and introduce adaptive management for embankments and barrages so river dynamics are respected. Finally, allocate sustainable finance—public and blended finance—earmarked for long-term ecological rehabilitation, not only short-term beautification.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Community Participation

Policies succeed only when communities hold a stake in implementation. Create local river committees that include fisherfolk, ghat families, women’s groups, farmers and youth representatives. These committees can co-manage waste segregation, localized sanitation, and seasonal livelihood plans. Promote community monitoring programs—simple mobile apps or paper-based scorecards—that allow citizens to report pollution, illegal dumping or changes in biodiversity. Support cooperative enterprises (for example: community-run composting, flower-waste processing, and sustainable fisheries) that convert conservation activities into livelihoods. Educational programs in schools and faith-based outreach can change behavior over time by linking stewardship to cultural values and daily practices.

Technology Opportunities

Appropriate technologies can dramatically improve outcomes if deployed with local ownership. Decentralized wastewater treatment systems (DEWATS) and constructed wetlands work well for small towns and peri-urban settlements. Bioremediation and phytoremediation techniques can help clean contaminated sediments and marginal drains. Smart sensor networks (low-cost probes and community dashboards) enable real-time water-quality tracking, informing quick responses and public transparency. For flood and erosion management, combine drone and satellite imagery with local knowledge to target interventions and plan restorations. Encourage industrial resource-recovery models—turn effluent into usable byproducts and reduce water withdrawal by adopting circular-economy practices.

Your Call to Action — Practical Steps You Can Take Now

Everyone can contribute. Here are simple, high-impact actions:

- Reduce single-use plastics; refuse plastic packaging during visits to ghats and temples.

- Participate in or organize a local river clean-up and adopt a small stretch of riverbank.

- Support community enterprises that process floral waste or run decentralized sanitation.

- Use local reporting tools to flag illegal discharges or blocked drains to authorities.

- Vote for and engage with leaders who commit to transparent river governance and long-term funding for clean water infrastructure.

The Ganga’s future will be shaped by policy choices, community resolve and the smart use of technology. When these three pillars align, the river can recover much of its ecological function while sustaining the livelihoods and cultural life that depend on it. Join the effort—small sustained actions multiplied across communities create the momentum that truly transforms a river.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Where does the Ganga originate, and why is its source significant?

The Ganga originates from the Gangotri Glacier in Uttarakhand, where the Bhagirathi stream begins its journey. Scientifically, the river is considered to form at Devprayag, where the Bhagirathi and Alaknanda rivers merge. Its Himalayan origin gives the Ganga its mineral-rich water, strong flow and cultural sanctity. The source is significant not only for hydrology but also for centuries of religious belief, pilgrimage traditions and ecological connectivity.

2. What are the major causes of pollution in the Ganga, and how can they be addressed?

The main causes of pollution include untreated domestic sewage, industrial effluents containing chemicals and heavy metals, and widespread plastic waste. Solutions require expanding sewage treatment capacity, enforcing strict industrial waste regulations, promoting biodegradable alternatives and improving waste management at ghats. Community engagement, clean-up drives and behavior-change programs are also essential for achieving long-term river health and reducing pollution at the source.

3. Are there endangered species in the Ganga, and what efforts are being made to protect them?

Yes, several species are endangered—including the Ganges river dolphin, gharial crocodile and various freshwater turtles. Conservation efforts involve dolphin monitoring, rescue-and-release programs, community-led turtle hatcheries, protected river stretches and scientific research on migration patterns. Local NGOs and government departments collaborate to reduce threats from fishing gear, habitat loss and pollution, showing early signs of population recovery in some stretches.

4. How do dams and canals affect the long-term health of the river system?

Dams and canals provide irrigation, hydropower and seasonal flood protection, but they also disrupt natural flow and sediment movement. This can degrade habitats, reduce biodiversity, increase pollution concentration and accelerate delta erosion. Farmers may face issues like waterlogging or insufficient canal supply, while fish migration patterns suffer. Sustainable water management, adaptive flow releases and scientific planning are essential to balance development with ecological stability.

5. What can individuals do to help restore and protect the Ganga?

Individuals can make a measurable difference by reducing plastic use, avoiding littering near riverbanks, participating in local clean-up initiatives and supporting community-led conservation efforts. Advocating for transparent governance, using municipal reporting tools for pollution incidents and choosing eco-friendly offerings during religious activities also help. Over time, collective community actions can significantly improve water quality and support long-term river restoration.

Conclusion — An Emotional Closure to the Journey

As I traced the Ganga’s story—from its icy Himalayan origins to the fertile plains and the fragile delta—one realization kept surfacing: the Ganga is not merely a river, but a living presence woven into the emotional, cultural and economic fabric of millions. I still remember the first time I watched the sun rise over a quiet ghat, the golden light shimmering on the water and the gentle hum of prayers filling the air. That moment felt timeless. Yet, understanding the river more deeply has revealed how fragile that beauty truly is.

The Ganga gives us far more than we acknowledge—water, food, faith, identity, and a sense of continuity across generations. But in return, we have burdened her with pollution, unplanned development and neglect. Despite this, the river still flows with resilience. Community-led clean-ups, policy reforms, scientific innovations and youth-driven environmental movements all reflect a growing determination to restore what has been lost. These sparks of hope show that meaningful change is possible when collective will aligns with responsible action.

Ultimately, protecting the Ganga is not the responsibility of a single institution—it is a shared moral duty. If we begin to see the river not just as a resource, but as a relative, a teacher, a heritage, our actions will naturally become more mindful. Let this be our commitment: to preserve, respect and revive the Ganga so that future generations, too, may stand on its banks and feel the same sense of wonder, peace and belonging that we once felt.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

References

- Government of India, Ministry of Jal Shakti — official reports on Ganga conservation and river management.

- Namami Gange Programme — national documents, guidelines and progress reports related to river restoration.

- Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) — water quality data, pollution assessments and scientific studies.

- Research papers and academic journals on the ecology, hydrology and biodiversity of the Ganga–Brahmaputra basin.

- Field interviews and observations collected from local communities, fisherfolk and ghat families.

- National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) — project documents on sewage treatment, biodiversity conservation and riverbank management.