Introduction: My Journey, Nature’s Silent Warnings, and the Purpose of This Article

A few years ago, I began noticing a change in the landscapes I had always taken for granted. The hills that once looked lush were turning pale, the familiar bird calls were slowly fading, and the small river near my hometown — the one that had never disappointed us during summer — had shrunk into a thin, lifeless stream. That was the moment I realized that biodiversity loss is not just a scientific phrase; it is a crisis unfolding quietly around us.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

I started asking myself a simple question: Why is this happening? Is it only the changing climate, or are we gradually tearing apart the very ecological fabric that keeps our world alive? And if this really is a crisis, then the most important question is: Can we still do something about it?

This article is my attempt to answer those questions — through a blend of personal observations, scientific insights, local experiences, and actionable steps that anyone can follow. My goal is to help you understand that biodiversity loss is not just about plants and animals; it is directly linked to our food, our water, our economy, our health, and the future we want to pass on to the next generation.

Throughout this article, I will guide you through three essential stages — understanding, feeling, and acting. You will learn why ecosystems are degrading, how this degradation impacts people and nature, and what practical steps individuals and communities can take to begin restoring balance. I will also share the lessons I learned while witnessing these changes up close — lessons that may ignite a spark of awareness and responsibility within you.

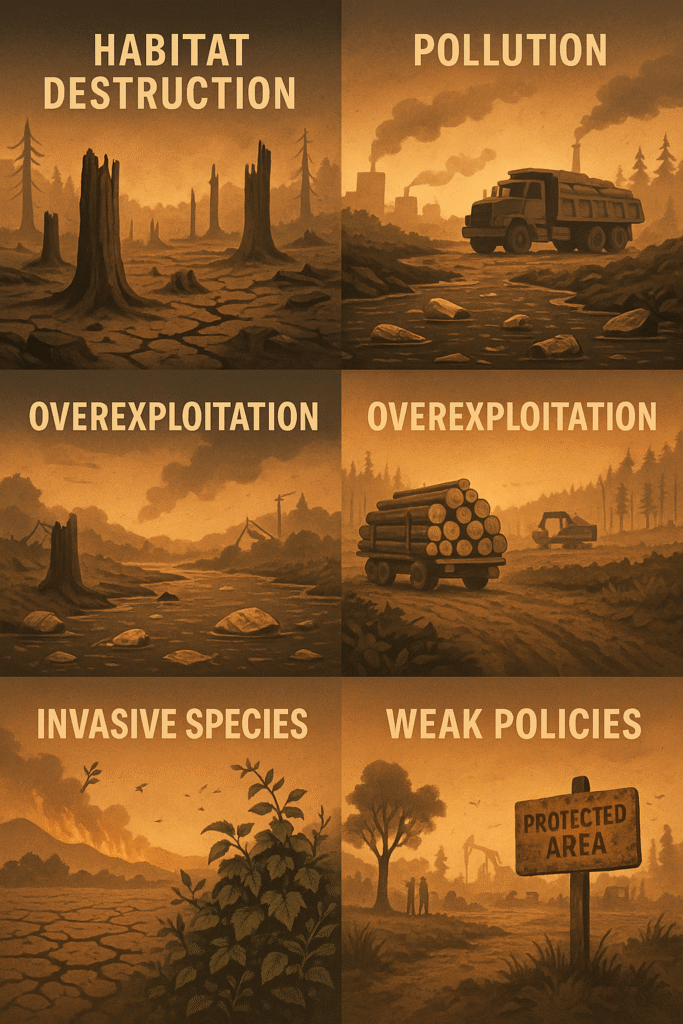

Why Is Biodiversity Declining? Major Causes Explained

Biodiversity loss is not the result of a single factor. It is a complex outcome of human actions, climate pressures, ecological imbalance, and unsustainable development practices. Understanding the root causes is essential if we want to reverse this trend and protect the ecosystems that support life. Below are the six major drivers of biodiversity loss that are reshaping natural habitats across the world.

1. Habitat Destruction

Habitat destruction is the single most significant reason behind global biodiversity decline. Expanding cities, commercial agriculture, road networks, mining, deforestation, and river modification have fragmented or erased natural habitats that species depend on for survival. When forests are cleared or wetlands drained, entire ecological communities collapse. I have personally witnessed once-dense patches of woodland near my region reduced to barren land within a decade. As the vegetation disappeared, the birds, insects, and small mammals that relied on it slowly vanished too. Habitat destruction not only eliminates space but breaks the interconnected relationships between species, making recovery extremely difficult. Once the natural home of a species is lost, it rarely returns to its original state.

2. Pollution

Pollution—whether chemical, plastic, air, noise, or light—has become one of the most silent but deadly threats to biodiversity. Pesticides, fertilizers, and industrial chemicals contaminate soil and water, weakening plants, poisoning freshwater life, and disrupting breeding cycles. Plastic pollution has grown into a global crisis, with microplastics now detected in rivers, oceans, birds, fish, and even human bodies. I remember how a local river that once supported turtles and freshwater fish gradually became choked with plastic bags, bottles, and chemical foam. The decline was visible, and yet unnoticed by many. Pollution does not just kill directly—it weakens immunity, alters habitats, and makes ecosystems more vulnerable to further stress.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

3. Overexploitation of Natural Resources

Humans have been extracting natural resources far faster than nature can replenish them. Overfishing, illegal wildlife hunting, excessive logging, overharvesting of medicinal plants, and unsustainable groundwater extraction have pushed many species to the brink of collapse. When fish populations decline due to overharvesting, entire marine food webs shift. When forests are logged at a pace faster than they regrow, not only trees but thousands of dependent insects, birds, and mammals decline with them. The imbalance between consumption and natural regeneration is widening rapidly. Overexploitation weakens ecosystems’ ability to bounce back, making them more vulnerable to climate change, invasive species, and further degradation.

4. Climate Change

Climate change has become a powerful and unpredictable force driving biodiversity loss worldwide. Rising temperatures, unpredictable rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, melting glaciers, forest fires, and warming oceans are forcing species to adapt, migrate, or vanish. Flowering seasons are shifting, migratory birds are arriving earlier or later than expected, and many animals are unable to cope with rapid environmental changes. Coral reefs are bleaching, polar habitats are shrinking, and tropical species are moving to higher altitudes in search of cooler climates. Climate change disrupts the delicate balance of ecosystems. Even small changes in temperature or rainfall can break the timing of pollination, breeding, and migration—leading to cascading effects across entire food chains.

5. Invasive Species

Invasive species—organisms that move or are introduced outside their natural range—pose a major threat to native biodiversity. These species often reproduce quickly, compete aggressively for resources, and lack natural predators in their new environment. I have seen invasive plants in rural regions spread so fast that they suffocated farmland and grassland areas within a few years, making it harder for native plants to survive. Aquatic systems face similar threats when non-native fish or plants disrupt local populations. Invasive species can alter soil chemistry, water availability, and entire habitat structures. Their impact often grows exponentially and is extremely difficult to reverse once established.

6. Weak Policies and Economic Pressures

Poor environmental regulations, weak enforcement, inadequate planning, and short-term economic priorities are major contributors to biodiversity loss. Development projects often proceed without proper ecological assessment, and communities directly affected by ecosystem degradation are rarely included in decision-making. Many industries and agricultural sectors prioritize quick profits over sustainable practices, putting long-term ecosystem health at risk. When policies fail to protect natural spaces, businesses and individuals default to practices that degrade land, water, and wildlife. Strong laws, community participation, and economic incentives for conservation are essential to reversing biodiversity decline. Without good governance, even well-designed conservation efforts struggle to succeed.

Impacts of Biodiversity Loss — Effects on Nature, Society, and Human Life

Biodiversity loss is not just about species disappearing quietly from forests, rivers, or oceans. Its impact reaches far beyond wildlife and touches the core of human existence — our food, water, economy, culture, and even our emotional well-being. When a species vanishes, the ecosystem loses one of its supporting pillars. Below are the major impacts of biodiversity loss that are now shaping our world in visible and invisible ways.

1. Ecological Impacts

Biodiversity forms the foundation of healthy ecosystems. When species decline, the natural balance collapses. Plants depend on pollinators; predators control herbivore populations; microbes keep soil fertile; and every organism plays a role in nutrient cycles. A decline in pollinators, for example, affects hundreds of plant species, leading to reduced seed production and weaker forests. Similarly, if soil organisms decrease, soil fertility drops, slowing down tree growth and affecting entire food webs. Even small disturbances create ripple effects throughout the ecosystem. A missing bird species might mean an insect population grows uncontrollably. A missing plant species may result in soil erosion. When ecosystems become unstable, their ability to recover from storms, fires, and climate shocks also weakens.

2. Impacts on Food and Water Security

Our food system relies entirely on biodiversity. Over 75% of global food crops depend on pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and birds. When these species decline, crop yields fall, threatening the livelihoods of farmers and food security for millions. Water systems are equally affected. Forests, wetlands, and grasslands naturally filter water, recharge groundwater, and regulate river flow. But when biodiversity declines in these ecosystems, rivers shrink, lakes dry faster, and groundwater levels drop. In many regions, I have seen ponds that once held water for months now drying up within weeks due to the loss of native vegetation. Reduced biodiversity directly affects agriculture, livestock, fisheries, and drinking water availability.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

3. Economic Impacts

A large portion of the global economy depends on nature — agriculture, fisheries, forestry, medicine, industry, and tourism. When biodiversity declines, these sectors suffer major financial losses. Farmers spend more on pesticides when natural pest-controlling species disappear. Coastal communities lose income when fish populations collapse. Tourism suffers when forests thin, wildlife disappears, or coral reefs bleach. The long-term economic cost of biodiversity loss is far greater than the short-term gains made through unsustainable development. Nations lose ecosystem services worth billions of dollars every year — most of which cannot be restored easily.

4. Impacts on Human Health

Healthy ecosystems regulate diseases naturally. When biodiversity declines, disease-spreading organisms such as mosquitoes, rodents, and ticks multiply faster. Studies show that deforestation and habitat fragmentation increase the risk of outbreaks like malaria, dengue, and Lyme disease. Many of the world’s medicines come from plants, fungi, and microorganisms. As these species disappear, we lose potential cures for future diseases. Biodiversity loss also affects mental health. Natural spaces reduce stress and anxiety, while degraded landscapes increase psychological distress — a phenomenon now known as “ecological grief.”

5. Social and Cultural Impacts

Many communities — especially Indigenous and rural groups — have cultural traditions, livelihoods, and identities deeply linked to local species and ecosystems. When forests degrade or species vanish, their cultural practices, folk stories, traditional knowledge, and even spiritual beliefs weaken. Biodiversity loss is not just ecological degradation; it is also the erosion of cultural diversity and heritage that has been preserved for centuries.

6. Emotional and Psychological Impacts

The decline of nature affects us emotionally. Watching rivers dry, forests shrink, or birds disappear triggers a deep sense of loss and helplessness. Many researchers call this feeling “ecological grief” — the sadness that comes from witnessing environmental destruction. Nature provides peace, inspiration, and emotional grounding. As natural spaces vanish, human well-being suffers. People feel disconnected, stressed, and mentally fatigued. Biodiversity loss is not only harming ecosystems; it is quietly reshaping the emotional balance of society.

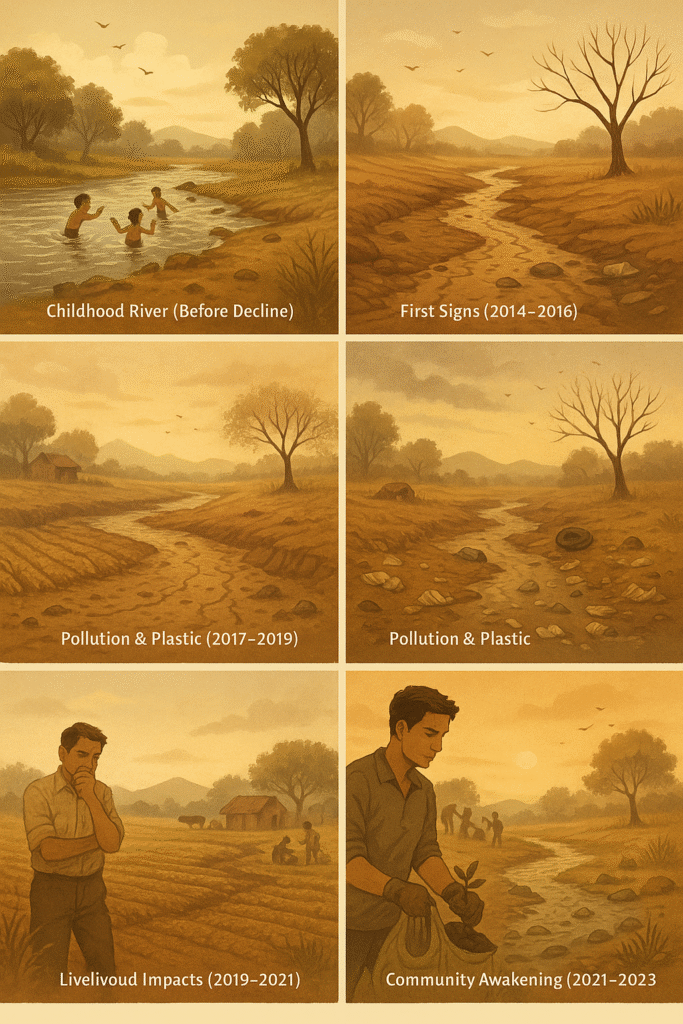

Case Study: My Personal Story — A River, a Village, and the Slow Disappearance of Biodiversity

Biodiversity loss is not a distant concept for me; it is something I have watched unfold right in front of my eyes. The village where I grew up had a small river running nearby — a river that was the heart of our childhood, our fields, our festivals, and our local economy. We called it our “lifeline.” No matter how harsh the summers were, the river always carried enough water to sustain people, animals, and crops. But over the last decade, I have seen that river slowly shrink, lose its color, lose its sounds, and lose its life. This is the story of how my understanding of biodiversity loss began — not from books, but from witnessing a living ecosystem collapse before my eyes.

First Signs: Changing Rainfall and Drying Landscapes (2014–2016)

Around 2014, the first warning signs became clear. The monsoon patterns began shifting. Rains arrived late, ended early, and often came in sudden bursts that didn’t replenish the soil. The river that once flowed steadily during summers began shrinking sooner than expected. Trees along the banks looked less vibrant, and dry leaves began covering the ground. Birds that once greeted every morning with their calls suddenly became fewer. At first, villagers believed it was a temporary “weather phase,” but the silence in the landscape felt unusual.

Farmers noticed something even more concerning — crop yields declined. The soil felt weaker, “tired,” as they described it. The natural insects that helped with pollination and pest control were becoming scarce. I didn’t know it then, but I was witnessing the first stage of biodiversity loss: the silent disappearance of the species that keep ecosystems functioning. It was no longer just a forest issue; it was becoming an agricultural and economic issue as well.

Second Signs: The River Shrinks and Plastic Takes Over (2017–2019)

In 2017, the river looked visibly smaller. For the first time in my life, I could walk across it without getting wet above my ankles. The water that once flowed strong was now slow, shallow, and fragmented. Kids who used to swim now avoided the river because the banks had become muddy, slippery, and filled with plastic waste. The disappearance of wildlife was even more heartbreaking. The small fish, freshwater turtles, and birds that were once abundant had almost vanished. What replaced them was garbage — plastic bags, bottles, wrappers, and even industrial waste carried from upstream areas.

Many locals dismissed these changes, saying, “Times are changing; this is natural.” But I could sense something deeper. The river was not just losing water; it was losing its ecological soul. With less water came fewer insects, which meant fewer birds. With fewer trees came fewer nesting sites, fewer fruits, and less shade. The entire ecosystem was unraveling, one thread at a time.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Third Signs: Community Struggles and Livelihood Impacts (2019–2021)

By 2019, the consequences had reached people’s lives in a way no one could ignore anymore. Farmers complained that the soil was no longer fertile. Where once a single irrigation was enough, they now needed twice as much water — water that was no longer available. The canals that once fed the fields were half-dry.

Many families began selling their cattle because fodder was becoming scarce. Youth started migrating to cities for work as agriculture became unpredictable. This was not just an environmental change — it was the slow breakdown of a village’s social and economic backbone.

The elders in the village would say, “When the trees went, the rain went. When the rain went, the people went.” Their words were simple, but they captured the heart of the crisis. For the first time, villagers began connecting the dots — reduced vegetation meant less rain, less rain meant dying rivers, and dying rivers meant dying livelihoods. It became clear that this was not merely a water problem; it was a biodiversity problem.

Fourth Signs: Awakening and Collective Action (2021–2023)

After years of decline, something changed around 2021. The crisis had become too visible to ignore, and finally, discussions began about doing something rather than waiting for things to fix themselves.

The village council organized river-cleaning drives. Local youth groups joined in, removing plastic, clearing blocked water channels, and planting new saplings along the riverbanks. I became part of this initiative as well. We set up a small nursery focused on native plant species — neem, acacia, khejri, rohida — the trees that naturally hold the soil together and survive in harsh climates. Slowly, very slowly, change began. A few bird species returned. Rainwater stayed longer in the riverbed. People felt a sense of ownership again — something they had lost over the years.

Five Key Lessons This Story Taught Me

- Nature always sends warnings — but humans often respond late.

- Biodiversity loss affects not just wildlife but agriculture, the local economy, and community well-being.

- Even small, community-led actions can trigger meaningful ecological restoration.

- Native species are more powerful than exotic ones in reviving dead or damaged ecosystems.

- Conservation only succeeds when people feel connected to the land they live on.

This story is not just about one river, one village, or one ecosystem. It represents thousands of places across the world where biodiversity is quietly disappearing and people are feeling the impacts in real time. But the most important message from this story is simple yet powerful: It is never too late to act — if we start today.

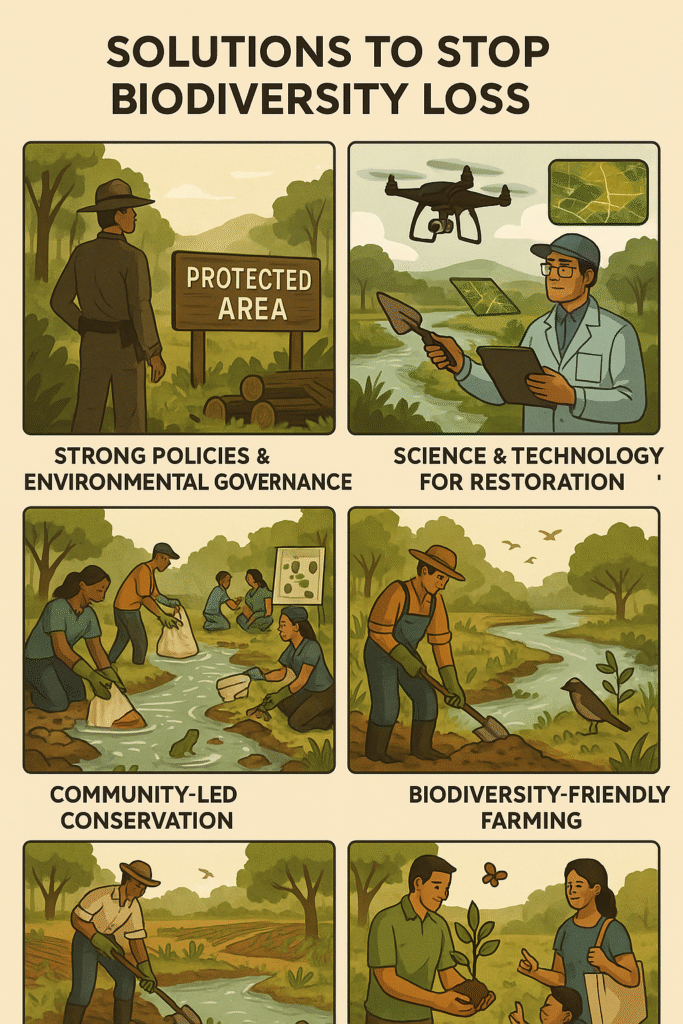

Solutions: Practical Actions to Stop Biodiversity Loss and Restore Our Ecosystems

Reversing biodiversity loss is not impossible. Nature has an extraordinary ability to heal itself when given the chance. Effective solutions require a combination of policy reforms, scientific innovation, community participation, and individual responsibility. Below are the most practical and impactful solutions to restore degraded ecosystems and protect the species we depend on.

1. Strengthening Policies and Environmental Governance

No conservation effort can succeed without strong environmental laws and their proper enforcement. Governments must expand protected areas, ensure transparent environmental impact assessments (EIA), regulate industrial waste, and impose strict penalties on illegal logging, poaching, and mining. Policies like Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) can motivate communities to take part in restoration efforts. When governance aligns with ecological science, ecosystems recover faster and more sustainably.

2. Scientific and Technological Approaches

Modern science offers powerful tools to restore damaged ecosystems. Restoration Ecology focuses on rebuilding degraded forests, wetlands, rivers, and grasslands using native species. Satellite data, GIS mapping, and drone surveys help identify degraded areas and track restoration progress. Techniques such as assisted natural regeneration, soil rehabilitation, and pollinator restoration have shown remarkable results in many regions. Technology allows us to measure, analyze, and act with precision — reducing guesswork and improving the speed of recovery.

3. Community-Led Conservation

The most successful conservation projects in the world are those led by local communities. When people living near forests, rivers, and wildlife habitats are directly involved, results become long-lasting. Community-driven actions such as river clean-ups, lake rejuvenation, grazing management, native plantation drives, and village-level biodiversity committees create a strong sense of ownership. I have personally witnessed significant improvements in areas where villagers regularly clean water bodies, protect native trees, and maintain common grazing lands. Conservation becomes sustainable only when people feel that the land belongs to them — not just legally, but emotionally.

4. Biodiversity-Friendly Farming

Agriculture and biodiversity are deeply interconnected. Unsustainable farming practices are a major cause of species decline, but they can also be part of the solution. Methods like agroforestry, crop rotation, organic farming, mulching, rainwater harvesting, and integrated pest management protect soil health and reduce chemical dependence. Planting hedgerows, flowering strips, and native trees around farms supports pollinators and birds, helping farmers naturally control pests and improve yields. When farms become ecological allies instead of extractive systems, biodiversity flourishes.

5. Reviving Water Ecosystems

Rivers, lakes, ponds, and wetlands are the backbone of all life forms. Reviving water systems involves desilting ponds, restoring river flow, removing plastic and chemical waste, planting native vegetation along banks, and reconnecting seasonal streams. Healthy water ecosystems attract birds, insects, amphibians, and fish — accelerating the return of biodiversity. Water restoration also improves groundwater recharge, stabilizes soil, and strengthens agricultural resilience.

6. Business, Startups, and Innovation

The private sector has a crucial role to play. Companies can adopt green supply chains, promote eco-friendly packaging, invest in carbon offset projects, and support large-scale restoration through their CSR programs. Startups are innovating biodegradable materials, pollution-reducing devices, and water-saving technologies — all of which help reduce pressure on ecosystems. When economic growth aligns with ecological health, restoration becomes both profitable and sustainable.

7. What Individuals Can Do

Even small individual actions can collectively create a massive impact. Everyone can:

- Plant and care for native trees that support local species.

- Reduce plastic use and ensure proper waste disposal.

- Avoid activities that disturb wildlife or damage natural habitats.

- Participate in clean-up drives and restoration campaigns.

- Support eco-friendly businesses and local conservation groups.

- Educate family, friends, and children about the value of biodiversity.

The most important truth is this: Biodiversity loss is reversible — but only if we act now. When governments, scientists, communities, and individuals move together, ecosystems begin to breathe again. Nature does not need miracles; it only needs commitment, consistency, and care.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Step-by-Step Action Plan — 10 Practical Steps to Restore Biodiversity

Saving biodiversity does not require huge budgets or government authority. Real change begins at the ground level — with individuals, families, local communities, and small groups taking consistent action. The following 10 steps form a practical, simple, and powerful framework that anyone can start today. When followed collectively, these actions can transform entire ecosystems.

Step 1: Start Observing Your Local Ecosystem

Awareness is the foundation of action. Begin by observing your surroundings — trees, birds, insects, soil conditions, water bodies, and seasonal changes. Take notes, click photos, and record month-to-month changes. This type of citizen science helps identify early ecological decline. Once you understand what is disappearing or changing, solutions become clearer and more targeted.

Step 2: Create a Nursery of Native Plants

Native plants are the backbone of biodiversity restoration. Choose local species such as neem, acacia, fig, oak, or region-specific native varieties. Start a small nursery — even 20–50 saplings can form a micro-ecosystem that supports birds, insects, and soil organisms. Communities can use this nursery to plant along rivers, roadsides, schools, and common lands.

Step 3: Reduce Plastic Usage by 50% in 30 Days

Plastic is one of the biggest killers of biodiversity. Set a personal challenge: “I will reduce my plastic usage by at least 50% in the next 30 days.” Use cloth bags, steel bottles, reusable containers, and compostable alternatives. If even 50 people from a community adopt this habit, plastic waste can reduce by 1–2 tons per year.

Step 4: Restore and Clean Local Water Bodies

Water systems recover very quickly when they are cleaned and protected. Organize weekly or monthly clean-up drives for ponds, rivers, streams, and lakes. Remove plastic waste, unblock natural water channels, and plant native vegetation along the banks. Within a few months, insects, frogs, birds, and small fish begin to return — reviving entire ecosystems.

Step 5: Build a Local Waste Management System

A community can significantly reduce ecological pressure by managing waste responsibly. Introduce separate collection for wet waste, dry waste, plastic, and e-waste. Convert wet waste into compost and send dry waste to recycling centers. This reduces pollution, protects water bodies, and enriches soil naturally.

Step 6: Promote Biodiversity-Friendly Farming

Farmers can play a crucial role in ecological recovery. Encourage practices like mixed cropping, crop rotation, mulching, organic fertilizers, and integrated pest management. Plant hedgerows, flowering strips, and native trees around farms to support pollinators and birds. These practices improve soil health, lower costs, and increase long-term agricultural resilience.

Step 7: Form a Community Conservation Group

Create a group of 10–15 people who regularly engage in conservation work — tree planting, clean-ups, awareness drives, and monitoring biodiversity. Small groups become the seeds of larger movements. Such groups can collaborate with schools, local governments, NGOs, and environmental clubs to build a strong network focused on restoration.

Step 8: Educate Children and Youth About Nature

The future of biodiversity depends on the next generation. Organize nature walks, bird-watching trips, plantation events, and “adopt-a-tree” programs for students. Encourage creative activities like photography contests, eco-art, poster-making, and science fairs focused on ecosystems. When children develop emotional connection with nature, they grow into responsible adults who protect it.

Step 9: Engage in Local Policy and Decision-Making

Join community meetings, municipal gatherings, and environmental discussions. Share data, photos, and reports you have collected. When citizens speak with evidence, local authorities respond more seriously. Advocate for protected green zones, restoration budgets, water conservation projects, and waste management reforms. Strong community participation ensures that conservation efforts are long-lasting.

Step 10: Monitor Progress and Adapt Over Time

Ecosystem restoration is a continuous process. Conduct monthly or seasonal assessments — track plant growth, observe returning species, update biodiversity lists, and monitor water quality. Modify strategies based on results. Small improvements add up and build powerful long-term impact. Nature responds slowly but surely — consistency is key.

This 10-step action plan can be applied in any village, town, or city. When individuals and communities work together, biodiversity returns, ecosystems heal, and natural balance is restored. The solution is not in waiting — the solution is in beginning.

FAQs — Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is biodiversity loss and why is it dangerous?

Biodiversity loss means a decline in the variety of plants, animals, insects, birds, and microorganisms in an ecosystem. It is dangerous because every species performs a vital ecological function such as pollination, soil restoration, water filtration, or maintaining the food chain. When species disappear, ecosystems lose their balance and become weaker over time.

2. Can a single individual really make a difference?

Yes, absolutely. Small actions such as planting native trees, reducing plastic use, participating in clean-up drives, or spreading awareness can collectively create large impacts. Every major movement in history started with a single committed individual. Nature restoration begins with simple, consistent actions.

3. Which plants are best for restoring biodiversity?

The best plants are always native species — those naturally found in your region. Native trees and shrubs support local birds, insects, pollinators, and soil organisms. For example, neem, acacia, fig species, oak, or region-specific native plants strengthen ecosystems faster than exotic or ornamental species.

4. How long does it take to see visible ecological improvements?

Some improvements appear within 2–4 months, such as the return of insects, birds, and better soil moisture. Larger transformations like forest regeneration, river restoration, or complete habitat recovery may take 2–5 years. Nature heals slowly but consistently if disturbances are removed and native species are restored.

5. What is the first step a community should take to protect biodiversity?

The most effective first step is restoring local water bodies. Clean rivers, ponds, and wetlands naturally attract species and help revive entire ecosystems. After this, communities can set up native plant nurseries, improve waste management, and run awareness programs.

6. Does agriculture contribute to biodiversity loss?

Yes, unsustainable farming practices such as monocropping, heavy pesticide use, and excessive groundwater extraction reduce biodiversity. However, methods like agroforestry, crop rotation, organic manure, mulching, and attracting pollinators can significantly increase biodiversity while improving farmers’ long-term yields.

7. How can we teach children about nature and biodiversity?

Take them on nature walks, encourage tree adoption activities, teach them about local species, and involve them in simple conservation tasks. When children develop emotional connection with nature, they grow into adults who protect it.

8. Is it possible to fully reverse biodiversity loss?

Yes, biodiversity loss can be reversed if strong policies, community participation, scientific methods, and individual responsibility work together. Nature has an extraordinary capacity to regenerate — it only needs protection, time, and consistent care.

Conclusion: Nature Is Calling — The Choice Now Belongs to Us

Biodiversity loss is not just an environmental concern; it is a defining challenge for our food security, economy, culture, and the survival of future generations. When a species disappears, it is not just one life that ends — an entire chain of ecological relationships weakens. Soil becomes poorer, water becomes scarce, climate patterns shift, and human well-being begins to decline.

Throughout this article, you have seen how small changes — a drying river, fewer birds, soil degradation — signal a larger ecological crisis. Yet, the most hopeful truth is that nature still has tremendous power to heal. The moment we stop harming it and give it time and space, restoration begins almost immediately.

The solution is not hidden in complex science or massive projects alone. It lies in our combined willingness to act — as individuals, families, communities, farmers, industries, and governments. A single tree planted today, a cleanup drive at a local water body, a child learning about nature, or a farmer choosing sustainable practices — these efforts may seem small, but together, they shape the future of entire ecosystems.

Today, nature is giving us a clear message: “Protect me, and I will protect you.” This is not merely a statement; it is the fundamental law of ecological balance. When we preserve biodiversity, we protect our food, water, climate stability, cultural heritage, and collective health.

The choice now lies with us — to wait passively or to begin actively. Remember, every major restoration movement begins with one small step. And that first step can be taken today — by you.

References / Further Reading

For reliable, science-based information on biodiversity, climate change, and ecosystem restoration, the following sources are highly recommended:

- IPBES Global Assessment Report — Comprehensive global study on biodiversity decline.

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) — Environmental data, policy insights, and global reports.

- IUCN Red List — Official international database of threatened and endangered species.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) — Research on agriculture, soil, forests, and water systems.

- WWF Living Planet Report — Analysis of global wildlife population and ecological trends.

- Local Forest & Environment Department Reports — Region-specific data on species and conservation efforts.

Studying these resources will help deepen your understanding of biodiversity loss, restoration strategies, and the global challenges shaping our natural ecosystems.