Introduction

The question of the "Arrival of the Aryans" is more than an academic puzzle — it touches history, identity, and methods of knowing the past. This introduction frames the debate as an interdisciplinary conversation that brings together archaeology, linguistics, textual studies, and contemporary social discourse. In the pages that follow, we will examine the kinds of evidence commonly invoked (archaeological remains, linguistic relationships, and passages from Vedic texts), show how those pieces fit — and where they conflict — and explain why a careful, balanced approach is essential for anyone attempting to draw conclusions about the distant past.

This essay lays out the major positions clearly: migration or invasion models that propose external arrival(s), and indigenous or local-development models that emphasize internal continuity and transformation. Rather than advocating a single viewpoint, the goal here is comparative and pedagogical — to highlight what each theory explains well, where the gaps remain, and which kinds of evidence carry greater weight in different contexts. Where possible, we prioritize primary archaeological reports, dated material evidence, and reproducible linguistic arguments; where uncertainty persists, we make that uncertainty explicit so readers can judge the strength of competing claims for themselves.

I also weave in my own research experience and reflections as a narrative thread — not to replace scholarly argument, but to model how a skeptical, source-driven inquiry can proceed. You will find practical notes on assessing primary versus secondary sources, reading dates and excavation reports critically, and recognizing when modern political or cultural concerns shape interpretations. By the end of this introduction you should have a clear map of the questions ahead, a sense of why they matter today, and a commitment to read the evidence with both intellectual rigor and cultural sensitivity.

|

Amazon Product Title HereBrief product description goes here. 👉 Check Price on Amazon |

Historical Background

The question of the Aryan arrival occupies a central and contested place in the ancient history of South Asia. Over the past two centuries scholars have proposed several models — from a single, dramatic migration or invasion to multiple waves of movement, and to theories that emphasize internal development and cultural continuity. Each model draws on different kinds of evidence: material remains recovered through archaeology, linguistic relationships revealed by comparative philology, descriptions and social details preserved in Vedic texts, and more recently, radiocarbon dates and genetic (aDNA) data. Taken together, these sources create a complex, sometimes contradictory, picture. Understanding that complexity is the first step toward a balanced interpretation: no single type of evidence can answer every question alone.

Historians and archaeologists who study the period generally ask three interrelated questions. First, did groups identified as “Aryans” enter the subcontinent from outside, or did the cultural and linguistic changes labelled “Aryan” emerge largely from local transformation? Second, when did these changes occur — were they concentrated in a narrow window of time or spread across many centuries? Third, what combination of processes (migration, trade, elite emulation, technological diffusion, or internal social evolution) best explains the observed patterns? Archaeology, linguistics and textual studies each contribute partial answers; the task of modern scholarship is to place those answers in conversation rather than treat any single dataset as definitive.

In practical terms, this means reading stratified excavation reports, calibrated radiocarbon dates, linguistic subgroupings, and passages from the Rigveda or related texts side by side. It also means attending to regional diversity: the subcontinent is not a single homogeneous space, and evidence from the northwest may tell a different story from evidence in the Gangetic plains or the Deccan. Finally, modern political and cultural claims often overlay these academic debates, so a careful historical approach distinguishes between what the evidence can demonstrate and how it has been used in contemporary narratives.

Archaeological Evidence

Major Discoveries

Archaeology provides the most tangible material record for discussing the period before and around the emergence of Vedic culture. The mature Harappan (Indus Valley) civilisation — with major urban sites such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira and Lothal — displays planned streets, standardized weights, elaborate craft production and hydraulic infrastructure dated broadly between roughly 2600–1900 BCE (regional variation applies). These urban complexes show a high degree of social organisation that, in many respects, differs from descriptions of later Vedic society.

After the decline of the mature Harappan phase, regional archaeological sequences record varied patterns: in some areas there is continuity in settlement and material culture; in others we see the appearance of new pottery styles, shifts in settlement size, and changes in subsistence practices. Excavations across the northwestern plains and adjacent regions have documented changes in material culture around the late second and early first millennium BCE — including different ceramic traditions, variations in domestic architecture, and new burial practices — which some scholars interpret as evidence of population movements or cultural contacts from beyond the subcontinent.

More recently, radiocarbon dating and ancient DNA studies have added new data points. Radiocarbon calibration has refined chronologies for key sites and cultural phases; aDNA analyses have shown genetic links and population movements in Eurasia, though their interpretation in relation to “Aryan” identities is complex and contingent on precise sampling, geographic scope, and the specific genetic signals examined. Importantly, archaeology rarely, if ever, produces a single smoking-gun for a migration hypothesis. Instead it reveals mixtures of continuity and change — suggesting that local transformations, long-distance contacts, and episodic movements all played roles in shaping the subcontinent’s early second-millennium BCE and first-millennium BCE transitions.

Linguistic Evidence

Vedic Language and Connections

Comparative linguistics has historically been central to the Aryan question. The observation that Sanskrit (especially the older Vedic Sanskrit used in the Rigveda), Old Persian, Greek, Latin and several other languages share systematic phonological and grammatical correspondences led nineteenth-century scholars to posit an Indo-European (Indo-Aryan/Indo-Iranian) family. Vedic Sanskrit preserves archaic linguistic features that allow linguists to reconstruct aspects of a shared ancestral language and to map relative divergences across time and space.

Linguistic arguments typically make two kinds of points. First, structural and lexical parallels indicate some degree of historical connection or shared ancestry among these languages; this implies either ancient migration, prolonged contact, or a common origin in a broader Eurasian linguistic landscape. Second, the internal diversity and stratification within Indo-Aryan languages permit relative dating and movement patterns: for example, the spread and differentiation of Indo-Aryan languages across northern India can be modelled as a complex process occurring over many centuries, not necessarily a single rapid incursion.

However, linguistic data alone cannot always determine demographic or cultural mechanisms. Borrowing, elite language replacement, and bilingualism can produce linguistic diffusion without large-scale population replacement. Consequently, scholars combine linguistic evidence with archaeological and genetic data to argue for scenarios that best fit the full body of evidence. In short, Vedic linguistic features are powerful clues to ancient connections, but their proper interpretation depends on integrating other lines of inquiry.

Concept of the Aryans: Definition and Sources

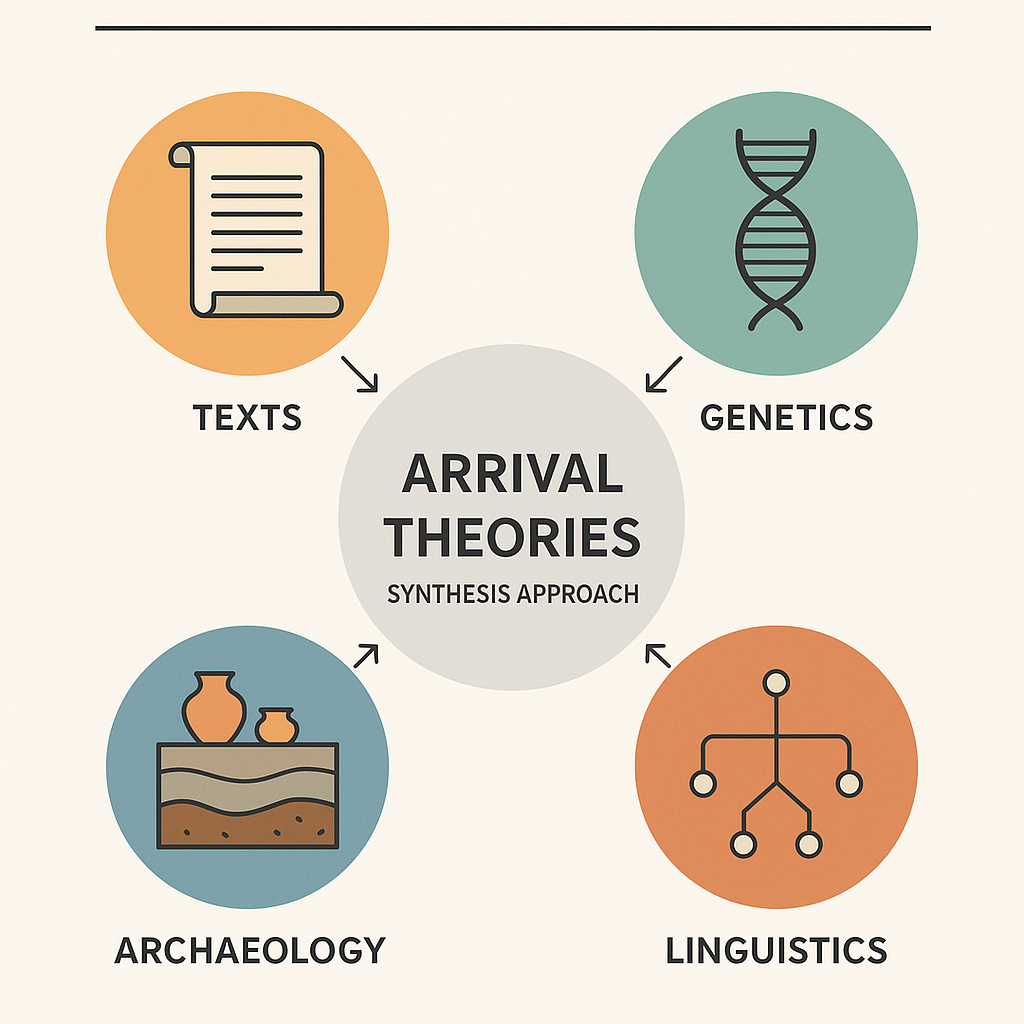

The term "Aryan" has been used in different ways across languages, texts, and disciplines — as a self-designation in ancient texts, as a linguistic category in comparative philology, and at times as a politicized identity in modern discourse. Clarifying what scholars mean by "Aryan" is essential before weighing competing historical scenarios. In academic work today, three source-types are routinely brought into conversation: textual evidence (primarily the Vedic corpus), linguistic evidence (comparative Indo-European/Indo-Aryan studies), and material evidence (archaeology, radiocarbon dating, and increasingly, ancient DNA). Each line of evidence speaks to different aspects of the past — belief and social practice, language relationships and diffusion, and material lifeways and demographic change — so a careful, integrated reading yields the most reliable inferences.

Methodologically, historians ask distinct but related questions: does "Aryan" denote a migrating people, a shared language-family, an elite cultural formation, or a suite of religious and social practices adopted by diverse groups? Is change in the archaeological record best explained by population movement, local innovation, or cultural diffusion? And how do textual descriptions — often ritualized, symbolic, and composed in later redactional layers — align with material chronologies? Because no single source provides exhaustive answers, contemporary scholarship emphasizes triangulation: matching textual clues with dated archaeological contexts and linguistic reconstructions to generate plausible historical scenarios while explicitly noting uncertainties.

|

Amazon Product Title HereBrief product description goes here. 👉 Check Price on Amazon |

Vedic Texts and the Term "Arya"

The oldest strata of Vedic literature (notably the Rigveda) use the term ā́rya in contexts that suggest social, ritual, and sometimes geographic distinctions. In many passages “ā́rya” functions as a cultural or moral category — those who observe particular rituals, speak certain dialects, or participate in shared ritual frameworks — rather than as a straightforward ethnic label. Vedic hymns also contain references to groups beyond the ā́rya, sometimes labeled as anā́rya, and include narratives of conflict, alliance, and mobility. Philological study of these texts helps establish relative chronologies (layers of composition), social vocabulary, and references to material culture (e.g., chariots, cattle, ritual implements) that can be compared with archaeological horizons.

Importantly, Vedic texts are not historical chronicles in the modern sense: they mix myth, ritual instruction, and social memory. As a result, scholars treat Vedic testimony as a source that requires contextualization — its value grows when used alongside securely dated archaeological contexts and linguistic evidence that can test hypotheses about timing and directionality of cultural change.

External Sources and Archaeology

External written sources (inscriptions from Iran and West Asia, later classical references) and material culture provide complementary perspectives. Archaeology records the rise, florescence, and transformation of the Harappan (Indus Valley) urban network and the varied regional trajectories that followed its decline. Excavations reveal patterns of continuity and change in pottery styles, settlement layout, burial practices, and subsistence that vary by region and period — sometimes consistent with population movement, sometimes suggestive of local adaptation and interaction.

In recent decades radiocarbon calibration and aDNA studies have added new, though careful, constraints: radiocarbon refines occupation sequences and cultural phases, while genetic data can indicate population admixture events and relative timings. Yet these scientific data require cautious interpretation: genetic links do not map cleanly onto cultural labels like "Aryan," and sampling limitations mean results are regionally specific. Ultimately, external textual markers and archaeology together show a patchwork of contact, continuity, and change — implying that the "Aryan" phenomenon is best understood as a complex historical process rather than a single, uniform event.

Arrival Theories

Scholars have long debated how to interpret the cultural, linguistic, and material changes in South Asia that are often linked with the so-called "Aryan" phenomenon. Two broad families of explanations dominate the literature: one emphasizes migration or external innovation (variously described as migration, infiltration, or invasion models), while the other stresses indigenous development, local transformation, and long-term internal processes. Modern research tends to treat these positions not as mutually exclusive absolutes but as complementary perspectives that must be tested against archaeological stratigraphy, dated material culture, linguistic reconstruction, and increasingly, genetic evidence. Below we summarize both approaches, clarify what kinds of evidence each relies on, and point out their respective strengths and limitations so readers can assess how each model fits different regional and chronological contexts.

Migration / Innovation Theory

The migration or innovation model proposes that at least some of the cultural and linguistic traits associated with "Aryan" identities arrived in the subcontinent through one or more movements of people or through the transmission of people-bearing innovations. Proponents point to several kinds of evidence: systematic parallels between Indo-European languages (suggesting a shared linguistic ancestry outside South Asia), apparent discontinuities or rapid changes in certain archaeological assemblages, and textual references in Vedic literature to social elements (such as chariot warfare and horse-based pastoralism) that appear more prominent in other Eurasian contexts. In archaeological sequences, arguments for migration often focus on the sudden appearance of new pottery types, novel domestic architecture, new burial customs, or changes in subsistence strategies that are difficult to explain by internal development alone. Recent aDNA studies that detect genetic admixture events between western Eurasian and South Asian populations during the second and first millennia BCE are sometimes cited as biological support for population movement. However, careful advocates of the migration model emphasize that the scale, tempo, and regional patterning of migration matter: the evidence more plausibly supports episodic, regionally-variable movements and cultural transmission rather than a single, continent-spanning invasion. Moreover, archaeological discontinuity can also arise from social reorganization, elite replacement, or networks of exchange that carry ideas and objects without large-scale demographic replacement. Thus, while migration/innovation explanations remain influential, they are most convincing when supported by tightly dated, region-specific correlations among material change, linguistic spread, and genetic signals.

Indigenous / Local Development Theory

The indigenous or local-development perspective argues that many of the transformations labeled as "Aryan" emerged principally from internal dynamics within the subcontinent — long-term social, economic, and cultural processes that reshaped communities after the decline of the urban Harappan network. Advocates of this view highlight archaeological strata that show continuity in pottery traditions, craft techniques, and settlement locations across supposed "transition" horizons; such continuity suggests gradual adaptation rather than wholesale population replacement. The indigenous model also stresses mechanisms like elite emulation, language shift through social acculturation, and multilingual or multilayered societies in which new ritual and political practices were adopted by local groups. Linguistically, this view allows for the spread of Indo-Aryan speech forms by processes such as elite dominance or progressive vernacular adoption rather than direct mass migration. Additionally, trade, long-distance exchange, and small-scale mobility can transmit technologies and ritual forms without necessitating demographic replacement. Critics of strict indigenous readings caution that indefinite appeals to local development can underplay clear instances of external contact; therefore, many scholars working in this tradition call for more regionally-specific data and a focus on fine-grained chronologies. In practice, the indigenous approach is most powerful when it demonstrates explicit archaeological continuity, local innovation, and plausible social mechanisms for language and ritual adoption that correspond to dated material sequences and textual signals.

|

Amazon Product Title HereBrief product description goes here. 👉 Check Price on Amazon |

In sum, contemporary scholarship increasingly favors synthetic or hybrid explanations that combine elements of both models: localized social transformations occurring alongside episodic external contacts, small-scale migrations, and selective adoption of foreign elements. The most persuasive reconstructions are those that integrate multiple datasets — stratified excavation results, calibrated radiocarbon dates, careful philological readings, and where available, genetic data — and that acknowledge regional variation rather than seeking a single, uniform process to explain the entire subcontinent.

Historians’ Disagreements

Scholars disagree about the Aryan question on several interlocking grounds: evidence weighting, methodological priorities, and interpretive frameworks. Some historians emphasize linguistic parallels and certain archaeological discontinuities as strong indicators of external movement into South Asia; for them, comparative philology and identifiable shifts in material culture form a coherent explanatory package. Others place greater trust in archaeological continuity and regionally fine-grained sequences, arguing that many observed changes can be explained by internal social transformation, trade networks, elite emulation, or long-term cultural diffusion rather than wholesale population replacement.

Debates also reflect different standards for causal inference. Where one researcher sees a sudden change in pottery or burial practice as evidence for population influx, another interprets the same pattern as adaptation or reorganization within existing communities. The arrival of aDNA and refined radiocarbon chronologies has complicated the picture rather than resolving it: geneticists report episodes of admixture and movement at certain times and places, but historians caution against equating genetic signals directly with cultural or linguistic categories like “Aryan.” Finally, disciplinary perspective matters—philologists, archaeologists, geneticists, and textual scholars each bring distinct questions and data; productive synthesis requires dialogue, careful cross-dating, and humility about the limits of any single line of evidence.

Impact on Modern Politics, Identity, and Education

Discussions about Aryan origins have substantial contemporary repercussions. Historical narratives are frequently repurposed in political discourse to support claims about national origins, ethnic primacy, or territorial entitlement. Competing reconstructions—migration-based or indigenous—are sometimes deployed symbolically to reinforce political agendas, shape identity politics, or legitimize cultural particularism. As a result, academic debates can become entangled with public memory and political mobilization, with consequences for social cohesion and minority rights.

In education, the controversy influences curricula and textbooks. Some educational frameworks prioritize source-critical, multi-perspectival history that emphasizes uncertainty and method; others present streamlined or ideologically framed accounts that favor a single explanatory narrative. These choices shape how generations understand the past and their place within it, affecting civic attitudes and intergroup relations. Media representations amplify the stakes: oversimplified headlines and selective evidence can harden public opinion.

Responsible scholars and educators therefore advocate transparency in method, explicit differentiation between evidence and interpretation, and pedagogies that teach students how to evaluate primary sources, dating techniques, and interdisciplinary arguments. Encouraging critical literacy—rather than rote acceptance of any single origin story—reduces the misuse of history and promotes a more nuanced civic culture.

My Experience and Lessons — A Narrative

I remember the afternoon I first read a handful of Rigvedic verses side by side with a dry excavation report: the juxtaposition felt like listening to two very different witnesses describing the same scene from separate rooms. One spoke in ritual cadence, metaphor, and moral prescription; the other listed layers of soil, pottery types, and calibrated dates. That moment began a long, often humbling process of learning how history is made — not discovered in a single strike of evidence, but assembled cautiously, piece by piece.

Early on I made the comfortable mistake of favoring elegant narratives. A neat migration story that tied language, pottery change, and a vivid Vedic image felt satisfying. Yet as I dug into primary reports, traveled to regional museums, and read contrasting field notes, I repeatedly encountered messy details: overlapping ceramic traditions, radiocarbon ranges that spanned centuries, and local practices that continued unchanged where a dramatic break had been supposed. These inconsistencies taught me the first hard lesson: plausibility is not the same as proof. A persuasive story must survive close scrutiny of the underlying data.

Fieldwork changed my perspective further. Standing on a terrace overlooking a small excavation, I saw how stratigraphy records human decisions—abandonment, rebuilding, gradual reuse—not always a clean break. Conversations with excavators emphasized context: a shard’s meaning depends on its layer, its association with hearths or pits, and the care with which samples were taken. Similarly, sitting with a linguist over a late-night cup of tea I learned to appreciate what comparative phonology can establish—and where it leaves room for multiple migration or contact scenarios.

Methodological humility became a personal commitment. I started annotating every claim with its evidence type: where did the pottery date come from, which lab produced the radiocarbon result, what was the sample context, and who translated the textual passage? When genetic studies arrived on the scene, I treated them as another dataset to interrogate — checking sample sizes, geographic coverage, and whether the authors drew careful distinctions between gene flow and cultural change.

The narrative approach helped me write for broader audiences. Rather than presenting history as settled verdicts, I began telling the story of investigation itself: the questions that guided a dig, the surprise in a lab result, the slow work of reconciling divergent sources. This made my work more transparent and invited readers to follow the reasoning, not just the conclusions. From those practices emerged clearer lessons: respect the limits of each source, triangulate across disciplines, and make uncertainty explicit rather than hiding it behind confident prose.

In short, my learning journey moved from appetite for tidy answers to a disciplined process of assembling complexity: read widely, consult original reports, listen to specialists, and always mark where evidence is strong and where it is provisional. That discipline, more than any single discovery, became the lasting reward.

How I Checked Sources

Primary vs Secondary

Source-checking became the backbone of my method. I treat primary sources as the raw material: excavation reports, stratigraphic diagrams, radiocarbon lab sheets, inscription photographs, and original language texts (in edition or facsimile). Primary evidence tells you what was actually recovered or recorded and under what circumstances. When possible I examine original field reports to verify context notes, sample provenience, and the exact wording of inscriptions or passages — because summaries and reprints sometimes omit critical qualifiers or caveats.

Secondary sources — journal articles, monographs, review essays — are indispensable for interpretation. They synthesize and evaluate primary data, propose arguments, and place findings in comparative frameworks. But I read them with questions in mind: Does the author cite the original reports? Is the argument peer-reviewed? What assumptions underlie their chronological model? When secondary accounts conflict, I trace both back to the same primary dataset and compare interpretations rather than choosing a side on face value.

Practical checks I always apply: confirm dates (calibrated radiocarbon values and lab IDs), inspect stratigraphic descriptions, review sample sizes and geographic spread for genetic studies, and verify translations and editions of textual passages. I also evaluate author credentials, the publication venue, and whether subsequent scholars have corroborated or contested the claims. Combining these steps — primary verification plus critical reading of secondary analysis — produces a much firmer basis for historical inference and helps prevent accepting a compelling narrative that lacks empirical support.

Conclusion

The question of Aryan origins does not yield to a single, definitive answer. Instead, it demands a multidisciplinary conversation that blends archaeology, linguistics, textual study, and modern scientific methods such as calibrated radiocarbon analysis and ancient DNA research. Archaeology highlights patterns of continuity and change that vary across regions; linguistics points to deep historical connections among Indo-European languages; Vedic texts preserve ritual memory, social vocabulary, and glimpses of early cultural landscapes; and genetic studies suggest episodes of admixture without mapping neatly onto cultural labels. When read together, these strands show that the emergence of Indo-Aryan cultures was not a single, abrupt event but a mosaic of interactions, adaptations, and regionally distinct processes.

Broadly speaking, some zones show clearer evidence of external contacts or limited-scale migrations, while many others reflect strong local continuities and gradual transformations. This mix cautions against rigid extremes — neither the idea of a sweeping invasion nor that of an exclusively indigenous origin captures the complexity revealed by the evidence. The most robust historical reconstructions are those grounded in transparent use of primary data, careful chronological reasoning, and open acknowledgement of uncertainties.

|

Amazon Product Title HereBrief product description goes here. 👉 Check Price on Amazon |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1) Who were the Aryans — were they migrants or indigenous?

The term “Aryan” historically refers to linguistic and cultural identities rather than a single ethnic group. Some evidence suggests episodes of external contact or limited migration, while many regions show strong local continuity. Most scholars agree that no single model—pure migration or pure indigeneity—adequately explains the diversity of evidence across South Asia.

2) Do Vedic texts provide direct evidence of Aryan migration?

Vedic texts are not historical chronicles; they are ritual, poetic, and philosophical compositions. They use the term “ārya” mainly in a cultural or ethical sense. While they offer insights into early social life and language, they do not explicitly record a migration event. Their information must be interpreted alongside archaeological and linguistic evidence.

3) What is the relationship between the Harappan civilization and the Aryans?

The Harappan (Indus Valley) civilization predates the Vedic tradition and represents a highly urban culture. Some regions show continuity after its decline, while others display gradual shifts in material culture. Although a direct cultural lineage is debated, evidence suggests possible interactions, exchanges, and shared technologies across overlapping periods and regions.

4) Has modern politics influenced the Aryan migration debate?

Yes. Competing interpretations have been used in political discourse to support narratives about identity, heritage, or territorial claims. This can sometimes oversimplify or distort scholarly findings. As a result, historians emphasize the need for neutral, evidence-based analysis to prevent misuse of ancient history for modern political agendas.

5) How reliable is archaeological evidence in this debate?

Archaeological evidence is highly reliable when contextualized properly—through stratigraphy, dating, and regional comparison. However, material change can arise from multiple causes, such as trade, adaptation, or small-scale movement. Therefore, archaeology provides essential clues but must be interpreted alongside linguistic and textual data for a complete picture.

6) Do genetic (aDNA) studies provide a final answer about the Aryans?

aDNA research reveals population mixing and long-distance interactions, but genetic signals do not map directly onto cultural categories like “Aryan.” Results vary by region and sample. Thus, genetics is a powerful tool, but meaningful conclusions emerge only when combined with archaeological and linguistic evidence.

7) What are the most reliable sources to study Aryan origins?

Primary data—excavation reports, radiocarbon dates, inscriptions, and original Vedic texts—are the strongest starting points. Peer-reviewed academic articles and scholarly books offer secondary interpretations. Cross-checking multiple types of evidence is essential for avoiding oversimplified conclusions.

8) Is a single, definitive conclusion about Aryan origins possible?

Current evidence points to a complex, multi-regional process. Some areas show signs of external contact, while many others reflect internal development. Because the data vary across regions and time periods, a single, universal conclusion is unlikely. A multidisciplinary, open-ended approach provides the most accurate understanding.

References

Primary Sources

- Rigveda (Original Texts and Translations) — Foundational source for understanding early Indo-Aryan language, ritual culture, and social concepts preserved in Vedic literature.

- Archaeological Excavation Reports — Official reports from sites such as Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Lothal, Rakhigarhi, etc., including stratigraphy, material culture, and calibrated radiocarbon dates.

- Ancient Inscriptions and Epigraphic Records — West Asian, Iranian, and Central Asian inscriptions that document early cultural and linguistic interactions.

- Scientific Dating Reports (Radiocarbon and Related) — Laboratory data used for verifying cultural phases and chronological contexts.

Secondary Sources

- Peer-reviewed Research Papers — Articles from journals in archaeology, linguistics, genetics, and historical studies offering comparative and critical interpretation.

- Academic Books — Scholarly works on early Indian history, Vedic culture, Indo-European linguistics, and the Harappan civilization.

- Linguistic Studies — Research on Indo-Aryan language origins, phonological and grammatical comparisons, and models of linguistic diffusion.

- Genetic Studies (aDNA) — Scientific analyses on human population history and admixture patterns; best used with contextual archaeological and linguistic data.

Useful External Links

- Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) — Official excavation reports and archives

- Open-access portals of universities and research institutes — Journals in archaeology, linguistics, and history

- Digital libraries — Digitized Vedic texts, inscriptions, and manuscripts