Introduction

The arrival of the Aryans remains one of the most debated and fascinating chapters in the history of the Indian subcontinent. For decades, historians, linguists, archaeologists, and researchers have explored the question of who the Aryans were, where they came from, and how their cultural presence shaped early Indian civilization.

The complexity of this topic arises from the diversity of evidence scattered across different fields — including linguistics, archaeology, genetics, and ancient texts. Each discipline offers valuable insights, but also comes with its own limitations, leading to multiple interpretations and ongoing debates.

In this article, I aim to present a balanced and research-based understanding of the Aryan arrival controversy. Along with scientific perspectives, I will also share personal reflections and experiences that shaped my understanding of this subject. My goal is to help readers approach this historical debate with clarity, curiosity, and an open mind.

Historical Background

Summary of Vedic Texts and the Types of References Found

The Vedic corpus — primarily the Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda — contains repeated references to the term "ārya" and related social, ritual and cosmological themes. In these hymns and ritual texts "ārya" usually appears as a cultural-ethical marker rather than a strictly biological or ethnic category. The Vedic literature records references to rivers, pastoral and agrarian livelihoods, sacrificial rites (yajña), chieftains and tribal encounters, as well as symbolic imagery such as horses and chariots.

Vedic passages include descriptions of social organization, ritual obligations, warfare, seasonal cycles and geographic names. These textual clues provide cultural context for early Iron-Age and late Bronze-Age societies in South Asia, but they are literary and ideological sources — not straightforward archaeological reports — so scholars combine them with material evidence to build historical reconstructions.

Contemporary Greek, Roman and Eastern References — A Brief Overview

Classical Greek and Roman authors (such as Herodotus, Megasthenes and later geographers) mention peoples and regions of the Indian subcontinent, offering outsider accounts that mix direct observation, traveler reports and second-hand hearsay. These sources occasionally describe Indian political organization, trade, and unusual customs, but they are often fragmentary and occasionally inaccurate.

Eastern sources, especially Old Iranian texts like the Avesta, use cognate terms (for example, Avestan “airya”) and reflect parallel cultural concepts found in Vedic material. Persian inscriptions and later classical Persian histories also refer to contacts, trade routes and political interactions across the northwestern frontier. Taken together, these Greek/Roman and Eastern references indicate that South Asia participated in long-distance networks of exchange and cultural contact from the late Bronze Age onward — but none of them provide conclusive, direct evidence for specific migration events on their own.

Timeline — Key Phases (compact)

~3000 BCE — 2000 BCE: Mature Indus (Harappan) Civilization

Urban centers, standardized crafts, long-distance trade and planned settlements characterize the mature Harappan phase.

~2000 BCE — 1500 BCE: Transitional and Regional Transformations

Regional cultural changes, shifts in settlement patterns, and new material elements appear across northwest South Asia; evidence of changing subsistence and mobility patterns increases.

~1500 BCE — 1200 BCE: Early Vedic Compositions and Cultural Formations

Composition of many Rigvedic hymns; formation of ritual traditions and social patterns often associated with early Vedic communities.

~1200 BCE — 1000 BCE: Expansion and Consolidation of Vedic Traditions

Gradual spread of Vedic cultural practices, development of social stratification, and increasing regional diversification set the stage for later historical periods.

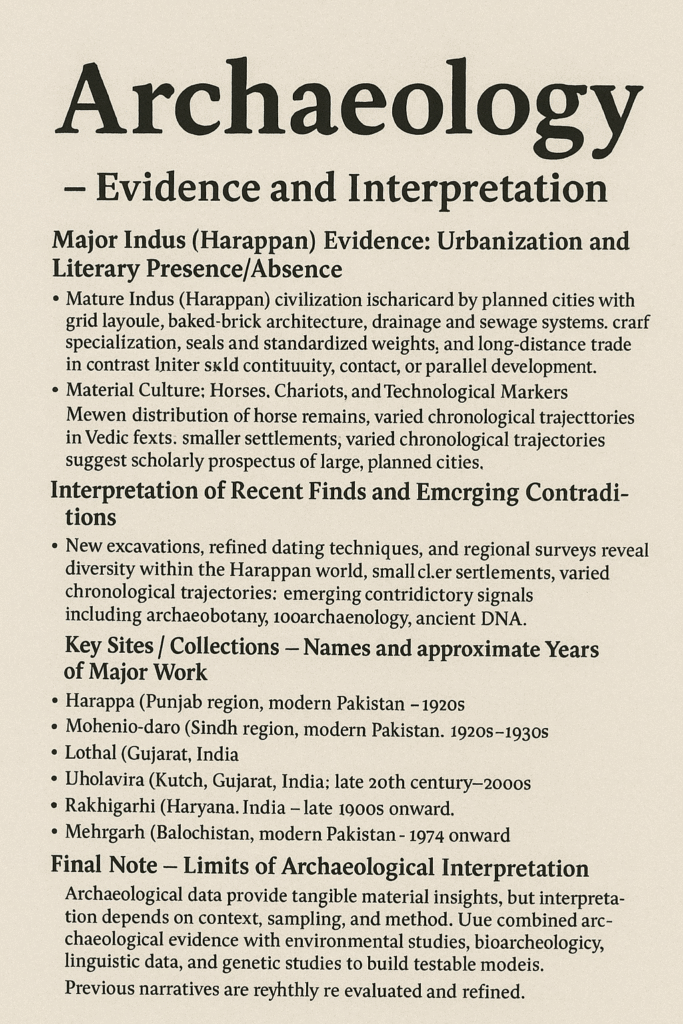

Archaeology — Evidence and Interpretation

Major Indus (Harappan) Evidence: Urbanization and Literary Presence/Absence

The Mature Indus (Harappan) civilization is characterized by striking archaeological features: planned cities with grid layouts, standardized baked-brick architecture, sophisticated drainage and sewage systems, craft specialization, seals and standardized weights, and evidence of long-distance trade. These elements point to a high level of urban organization and an integrated material culture across a broad geographic area in northwest South Asia.

In contrast to the rich urban material record of the Indus settlements, direct literary evidence that can be unambiguously linked to Harappan urban institutions is lacking. The core Vedic corpus (e.g., Rigveda) does not provide clear descriptions of large, planned cities comparable to Harappan urbanism. This difference—urban archaeological complexity on the one hand, and predominantly pastoral/ritual literary imagery in early Vedic texts on the other—has led scholars to propose a range of models for continuity, contact, or parallel development between these cultural spheres.

Material Culture: Horses, Chariots, and Technological Markers

Textual references in Vedic literature to horses (aśva) and chariots (ratha) are prominent, but the Harappan material record shows an uneven distribution of clear horse remains and chariot-related evidence. While some regions and later contexts provide stronger support for horse usage, many major Harappan urban centers exhibit limited or debated traces of equine remains. Scholars therefore caution against using a single artifact class as definitive proof for large-scale population movements or cultural replacement.

Interpretation of Recent Finds and Emerging Contradictions

Over the last several decades, new excavations, refined dating techniques (e.g., improved radiocarbon sequences), and regional surveys have revealed far greater diversity within the so-called Harappan world. Smaller, contemporaneous settlements, regional craft traditions, and varied chronological trajectories suggest a complex mosaic rather than a single monolithic culture. Some newly reported sites show local developmental trajectories that complicate any simple “collapse-and-replacement” narrative.

At the same time, some recent claims—whether from small-scale surface finds, contested osteological identifications, or preliminary genetic sampling—have produced contradictory signals that require cautious interpretation. New data often refine or revise earlier models, and in several cases they highlight the need for integrated multi-disciplinary analysis (archaeology + archaeobotany + zooarchaeology + ancient DNA + landscape archaeology) before firm conclusions can be drawn.

Key Sites / Collections — Names and Approximate Years of Major Work

- Harappa (Punjab region, modern Pakistan) — recognized as a major site and excavated in phases beginning in the 1920s (notably early investigations in 1920–1921); subsequent excavations and research continued through the 20th century into the present.

- Mohenjo-daro (Sindh region, modern Pakistan) — large-scale excavations and site recognition took place primarily in the 1920s–1930s; the site has been subject to ongoing conservation and survey work since then.

- Lothal (Gujarat, India) — excavated in the 1950s (major work in the mid-to-late 1950s); identified as an important maritime/harbour-related Harappan site with evidence of craft and trade.

- Dholavira (Kutch, Gujarat, India) — survey and research identified the site in the mid-20th century; formal excavations and major publications date from the late 20th century into the 1990s and 2000s; Dholavira has become central to debates about urban planning and regional variation.

- Rakhigarhi (Haryana, India) — surveyed in the mid-20th century with significant excavations and renewed attention from the late 1990s onward (multiple field seasons from c.1997 onward); regarded as one of the larger Harappan urban centers in the Indian plains.

- Mehrgarh (Balochistan, modern Pakistan) — long-term excavations began in the 1970s (notably 1974 onward) revealing a sequence from early farming communities (Neolithic) through Chalcolithic phases; Mehrgarh is crucial for understanding pre-urban developments in the region.

Final Note — Limits of Archaeological Interpretation

Archaeological data provide tangible, material insights into past lifeways, but interpretation depends on context, sampling, and method. Single finds or isolated datasets are rarely conclusive by themselves. When assessing the relationship between the Indus material world and early Vedic textual traditions, researchers therefore combine archaeological evidence with environmental studies, bioarchaeology, linguistic data, and increasingly, genetic studies to build careful, testable models. As new discoveries and methods appear, previous narratives are rightfully re-evaluated and refined.

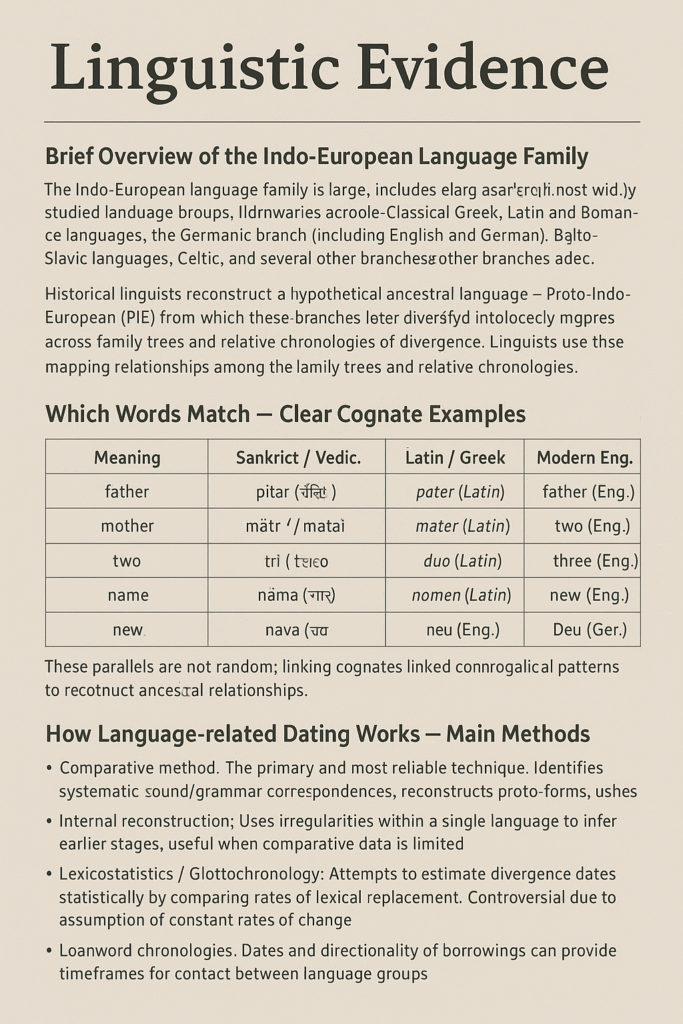

Linguistic Evidence

Brief overview of the Indo-European language family

The Indo-European language family is one of the world's largest and most widely studied language groups. It includes early Sanskrit and its descendants, Old Iranian (Avestan, Old Persian), Classical Greek, Latin and the Romance languages, the Germanic branch (including English and German), Balto-Slavic languages, Celtic, and several other branches. Historical linguists reconstruct a hypothetical ancestral language — Proto-Indo-European (PIE) — whose descendants later diversified into these branches.

Comparative study of systematic sound correspondences, shared grammatical features, and cognate vocabulary allows linguists to map relationships among these languages and to propose family trees and relative chronologies of divergence.

Which words match — clear cognate examples

Below are some widely cited cognates (similar inherited words) that illustrate regular correspondences across Indo-European branches:

| Meaning | Sanskrit / Vedic | Latin / Greek | Modern English / Germanic |

|---|---|---|---|

| father | pitar (पितृ) | pater (Latin), patēr (Greek) | father (Eng), Vater (Ger) |

| mother | mātṛ / matar (मातृ) | mater (Latin) | mother (Eng) |

| two | dvi / dwo (द्वि) | duo (Latin) | two (Eng) |

| three | tri (त्रि) | tres (Latin), treis (Greek) | three (Eng) |

| name | nāma (नाम) | nomen (Latin) | name (Eng) |

| new | nava (नव) | novus (Latin) | new (Eng), neu (Ger) |

These parallels are not random: regular sound shifts and morphological patterns link the cognates. Linguists use those regularities (not isolated resemblances) to reconstruct ancestral forms and to infer genealogical relationships.

How language-related dating works — main methods

- Comparative method: The primary and most reliable technique. It identifies systematic correspondences in sounds and grammar across related languages, reconstructs proto-forms, and establishes relative branching orders (which languages separated earlier or later).

- Internal reconstruction: Uses irregularities within a single language to infer earlier stages of that language, useful when comparative data are limited.

- Lexicostatistics / Glottochronology: Attempts to estimate dates of divergence statistically by comparing rates of replacement in basic vocabulary. This method is controversial because it assumes roughly constant rates of lexical change, which is often unrealistic.

- Loanword chronologies: Dates and directionality of borrowings (e.g., agricultural, technological terms) can provide relative timeframes for contact between language groups.

- Areality and contact studies: Mapping geographic patterns of shared features helps distinguish inheritance from contact and can suggest approximate sequences of diffusion.

Limits and cautions

Linguistic dating is powerful but has important limitations:

- Borrowing versus inheritance: Shared words may be borrowings (loanwords), not inherited cognates, so each candidate cognate must be tested against regular sound change patterns.

- Non-constant change rates: Languages change at variable rates influenced by social, technological, and demographic factors; therefore simple clock-like models are unreliable in many cases.

- Methodological assumptions: Methods like glottochronology rest on assumptions that are often challenged by empirical evidence, making absolute dates uncertain.

- Data selection: Choice of “basic” vocabulary or features affects statistical estimates; fragmentary data for ancient stages reduce confidence.

- Complementary evidence required: Linguistic results are strongest when integrated with archaeological, genetic and historical data — alone they rarely provide precise absolute dates for population movements.

Short conclusion

Linguistic evidence convincingly demonstrates deep genetic relationships among many Eurasian languages and provides a framework for hypotheses about historical connections. However, linguistic dating works best as part of a multi-disciplinary approach: it suggests relative sequences and probable contacts, while archaeology and genetics help test and refine absolute chronologies.

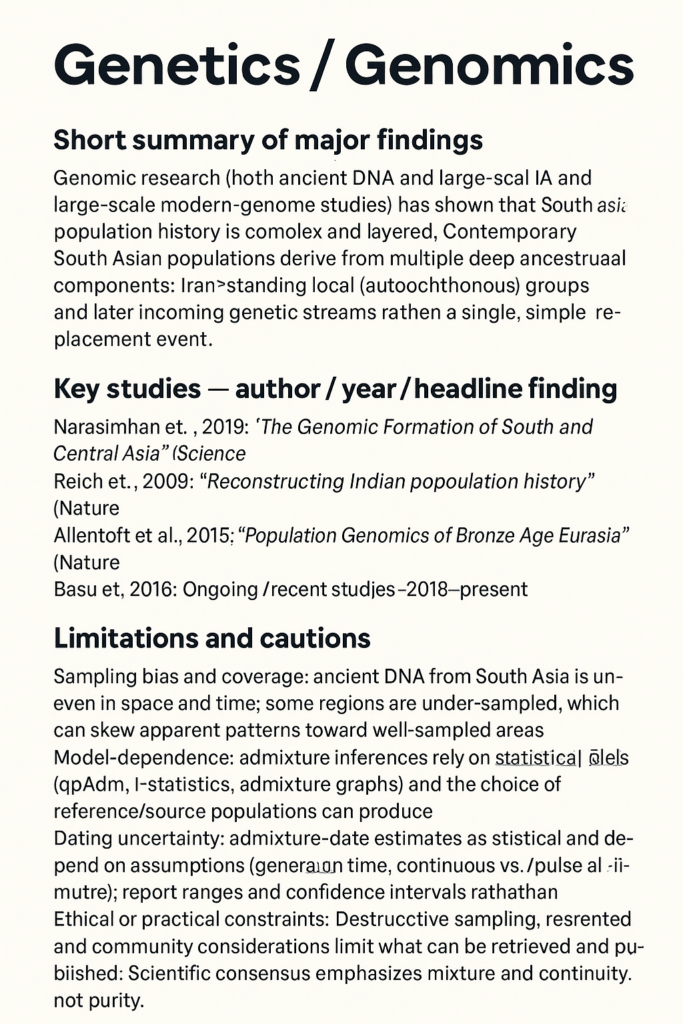

Genetics / Genomics

Short summary of major findings

Over the last decade genomic research (both ancient DNA and large-scale modern-genome studies) has shown that South Asia's population history is complex and layered. Contemporary South Asian populations derive from multiple deep ancestral components: long-standing local (autochthonous) groups together with later incoming genetic streams (for example, Iran-related and Steppe-related ancestries). Overall the data point to repeated admixture and regional variation rather than a single, simple replacement event.

Key studies — author / year / headline finding

- Narasimhan et al., 2019 — “The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia” (Science)

Analysed hundreds of ancient genomes and modelled admixture among Iran-related farmers, South Asian hunter-gatherer groups, and incoming Steppe-related ancestry; identified a notable spread of Steppe-related ancestry into parts of South Asia during the 2nd millennium BCE (ancient sample set ≈500+). - Reich et al., 2009 — “Reconstructing Indian population history” (Nature)

One of the foundational genome-wide surveys of modern Indian populations that proposed the ANI (Ancient North Indian) / ASI (Ancient South Indian) model and demonstrated widespread mixture in the subcontinent. - Allentoft et al., 2015 — “Population Genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia” (Nature)

A continental-scale ancient-DNA study documenting major Bronze-Age population movements from the Eurasian Steppe that provide a broader context for Steppe-related genetic inputs into Asia and Europe. - Basu et al., 2016 — (PNAS)

Extensive modern-genome analyses highlighting multiple ancestral components across Indian populations (beyond a simple two-way model), including regional heterogeneity and East Asian-related signals in some groups. - Ongoing / recent studies (2018–present)

A succession of ancient-DNA papers and preprints continue to expand geographic and temporal sampling, refine admixture dates and improve resolution for regional case studies.

Limitations and cautions

- Sampling bias and coverage: ancient DNA from South Asia is still uneven in space and time; some regions are under-sampled, which can skew apparent patterns toward well-sampled areas.

- Model-dependence: admixture inferences rely on statistical models (qpAdm, f-statistics, admixture graphs) and the choice of reference/source populations; different model choices can produce different interpretations.

- Dating uncertainty: admixture-date estimates are statistical and depend on assumptions (generation time, continuous vs. pulse admixture); report ranges and confidence intervals rather than single-point dates.

- Ethical & practical constraints: destructive sampling, permissions, and community considerations limit what can be retrieved and published; this affects which regions and periods are represented in the data.

- Political misuse: genomic results can be (and have been) misrepresented in public discourse to support deterministic or exclusionary identity claims. Scientific consensus emphasizes mixture and continuity, not purity.

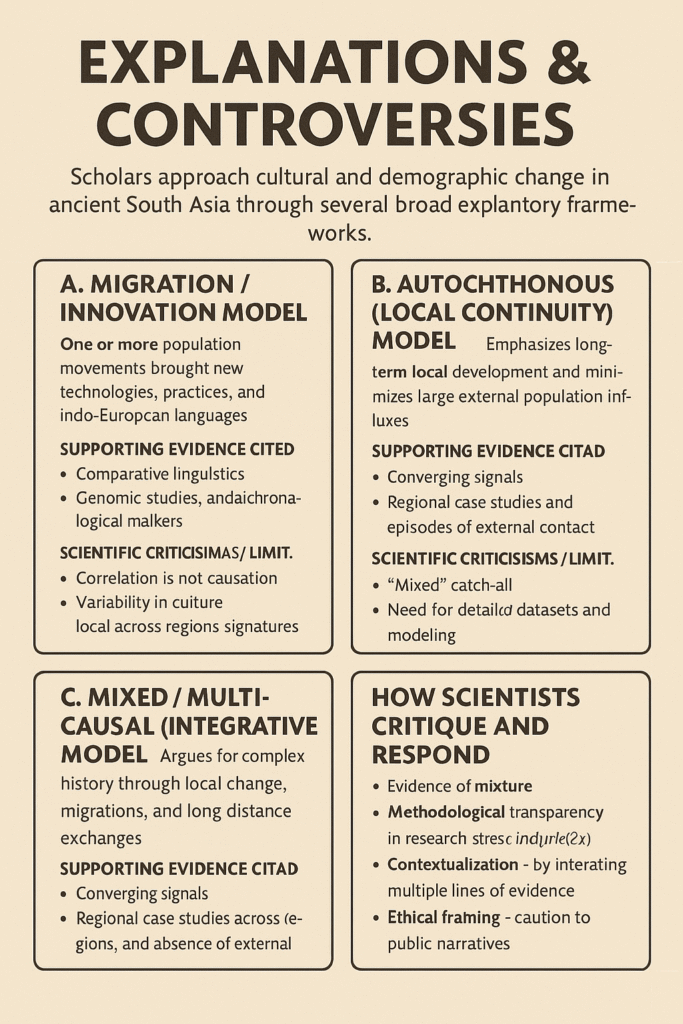

Explanations & Controversies

Scholars approach the question of cultural and demographic change in ancient South Asia through several broad explanatory frameworks. The three most widely discussed models are: (A) Migration / Innovation, (B) Autochthonous (local) Development, and (C) Mixed or Multi-causal models. Below each model is summarized, followed by common scientific criticisms and caveats. After that the section covers how political or nationalist narratives sometimes appropriate the debate and how scientists respond.

A. Migration / Innovation Model

Main claim

Proponents argue that one or more population movements into South Asia (from the northwest or Eurasian steppe regions) brought new technologies, social practices, and languages. These incoming waves are proposed to have introduced or accelerated innovations such as horse-based pastoralism, certain chariot technologies, and Indo-European languages in parts of the subcontinent.

Supporting evidence typically cited

- Comparative linguistics showing affinities between Indo-European languages.

- Genomic studies indicating gene-flow from steppe-related populations at Bronze-Age / Iron-Age horizons.

- Some archaeological markers (in select regions) that appear temporally associated with new material traits.

Scientific criticisms / limitations

- Correlation is not causation: linguistic similarity or genetic inflow does not automatically prove a single rapid population replacement; multiple scenarios can fit the data.

- Archaeological record is regionally variable — many major urban Harappan centers show little unambiguous evidence for equine/chariot assemblages claimed as diagnostic in some models.

- Timing and scale: genomic admixture dates and archaeological chronologies carry uncertainty and often point to gradual, multi-phased processes rather than one-off mass migrations.

B. Autochthonous (Local Continuity) Model

Main claim

This perspective emphasizes long-term local development: cultural change is largely the result of internal evolution, regional adaptation, and sustained continuity among indigenous communities. It minimizes the explanatory role of large external population influxes.

Supporting evidence typically cited

- Continuities in material culture and settlement patterns in many regions across long time spans.

- Archaeological sequences that show local innovation and complex regional interaction within South Asia.

- Interpretations that highlight the absence of clear archaeological signatures for wholesale population replacement at key sites.

Scientific criticisms / limitations

- Some genetic and linguistic signals are difficult to reconcile with a strict local-only model and suggest some degree of external contact or gene flow in parts of the subcontinent.

- Local continuity and external influence are not mutually exclusive; purely autochthonous models may underplay the role of long-distance trade, mobility, and exchange networks.

- Demonstrating absolute continuity requires dense, well-dated ancient DNA and high-resolution local stratigraphy — which are unevenly available across the region.

C. Mixed / Multi-causal (Integrative) Model

Main claim

The mixed model argues that the historical reality is complex: local development, intermittent migrations, cultural diffusion, environmental change, and technological transfer all contributed at different times and places. No single mechanism explains every pattern across the subcontinent.

Supporting evidence typically cited

- Converging but distinct signals in archaeology, linguistics and genomics that together point to multiple, regionally specific processes.

- Regional case studies showing both deep local roots and episodes of external contact or admixture.

Scientific criticisms / limitations

- “Mixed” can become a catch-all—without careful specification it risks being descriptive rather than explanatory.

- The model demands detailed, multi-disciplinary datasets and careful modeling to tease apart the relative importance of different factors in each region and period.

Political & Nationalist Claims — Forms and Scientific Responses

Common political / nationalist narratives

- Purity or autochthony claims: assertions that a particular modern group is the direct, unchanged descendant of an ancient people and that no significant external influence occurred.

- Replacement narratives: simple stories of total external takeover that erase continuity and local complexity.

- Selective appropriation: cherry-picking genetic, archaeological or textual fragments to support contemporary identity politics or claims of cultural superiority.

How scientists critique and respond

- Evidence of mixture: genomic, archaeological and linguistic data overwhelmingly point to admixture, layered contacts and continued interactions — not purity. Scientists emphasize continuity plus change rather than wholesale replacement or purity myths.

- Methodological transparency: researchers stress model assumptions, uncertainty ranges, and the need to report sample provenance and dating data so that claims cannot be overstated or misused.

- Contextualization: scholars integrate multiple lines of evidence (archaeology + aDNA + linguistics + paleoenvironmental data) before making strong historical claims; single-discipline claims are treated cautiously.

- Ethical framing: scientists call for caution when translating technical results into public narratives and urge that genetic/archaeological findings should not be used to justify modern exclusionary politics.

Practical writing tips for this section

- When describing any model, specify which types of evidence support it (e.g., “This inference is based on genomic admixture dates and limited equine osteology at site X”).

- Avoid absolutist language; use probabilistic phrasing (“the data suggest”, “evidence is consistent with”, “one plausible interpretation is”).

- When discussing political misuse, show how scientific uncertainty and model-dependence undermine simplistic claims — cite peer-reviewed studies rather than popular summaries where possible.

- Encourage readers to see the debate as productive: competing models stimulate better data collection and refined hypotheses.

Cultural Impact & Contemporary Relevance

Why this debate matters today

The debate over the arrival of the Aryans is not just an academic exercise in reconstructing deep history — it shapes modern education, collective identity, and public policy. How scholars and publics interpret the past affects school curricula, heritage projects, identity narratives, and even political rhetoric. For these reasons, responsible presentation of evidence and clear communication of uncertainty are essential.

Education

Curricula and textbooks

School and university curricula are often the first place historical narratives become socially shared. Decisions about which interpretations to teach — migration models, indigenous continuity, or integrative views — influence generations' understanding of national and regional history. Single-perspective or politicized textbooks can distort students' understanding and critical skills.

Practical recommendations for teaching

- Present multiple models (Migration, Indigenous, Mixed) and explain the evidence and limitations of each.

- Use primary-source exercises (text excerpts, archaeological reports, maps) to teach source-evaluation and critical thinking.

- Encourage interdisciplinary projects that combine archaeology, linguistics and genetics to demonstrate how different evidence types interact.

Identity and social consequences

Collective identity formation

Historical narratives often become part of collective self-understanding (“where we come from”). When simplified or absolutist claims dominate, they can be used to promote exclusivist identity politics or cultural superiority. Emphasizing complexity, mixture, and long-term change counters simplistic ethnic or racial myths.

Inclusion versus exclusion

Framing the past as mixed and interconnected supports inclusive identities and multicultural narratives. By contrast, claims of pure descent or single-origin histories can be mobilized to exclude groups, limit cultural recognition, or justify discriminatory policies.

Public policy

How historical narratives influence policy

Interpretations of the past inform policies on heritage protection, museum curation, curriculum standards, cultural funding, and commemorations. Policy-makers may cite historical claims to prioritize certain monuments, festivals, or narratives—therefore evidence-based advisory panels and transparent sourcing are important before adopting history-driven policies.

Areas affected

- Education policy and textbook review boards

- Museum and heritage site programming

- Public funding for cultural or commemorative projects

- Legal/administrative claims where historical continuity is argued (where relevant)

Media, public discourse and misinformation

Popular media and social platforms amplify historical claims rapidly; simplified or sensationalized headlines can generate misunderstanding and polarized reactions. Journalists, editors, and content creators should prioritize expert consultation, provide source links, and avoid overstating single-study results.

Practical media guidelines: include expert voices, link to original research, use cautious language (e.g., “evidence suggests” rather than “this proves”), and provide context about uncertainty and alternative interpretations.

Guidance for community groups and cultural institutions

- Involve local communities in heritage projects and exhibition planning to ensure multiple perspectives are represented.

- Organize public lectures and moderated panels with scholars from relevant disciplines to foster informed local dialogue.

- Create accessible resource lists (reading lists, museum trails, annotated bibliographies) so citizens can consult reliable sources themselves.

Conclusion

The debate surrounding the arrival of the Aryans is far more than a question of ancient chronology—it is a window into how cultures evolve, interact and transform over time. The combined insights of archaeology, linguistics and genetics demonstrate that South Asia has always been a region shaped by diversity, continuity, innovation and periodic waves of contact. No single event or community can fully explain the complexity of its cultural foundations.

Scientific evidence consistently shows that human history is characterized by movement, exchange and adaptation rather than rigid purity or isolated origins. This understanding challenges simplistic or politically motivated narratives and encourages a more nuanced, evidence-based view of the past. Acknowledging mixture and multiple influences does not diminish cultural heritage; instead, it enriches it and broadens our appreciation for shared human experiences.

In the modern world, where historical narratives influence education, identity and public policy, it becomes even more important to handle such debates responsibly. Presenting history with transparency, balanced interpretations and clear references helps build an informed society capable of critical thinking rather than polarized assumptions.

Ultimately, the lesson this debate offers is both simple and profound: embracing complexity, diversity and interdisciplinary understanding leads to a more inclusive and intellectually honest engagement with our past. Such an approach not only deepens our knowledge but also strengthens the values of dialogue, respect and collective progress.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is the arrival of the Aryans considered a historical fact?

Scholars differ in their interpretations. Some genetic and linguistic studies suggest waves of migration into South Asia, while others emphasize long-term local development. Most modern researchers support a mixed model that includes both local continuity and external interactions.

Q2: Does the word “Aryan” refer to a race?

No. In the Vedic texts, the term “Arya” refers to cultural and ethical qualities, not to a biological race. Modern science also rejects the notion of a “pure Aryan race,” highlighting instead a long history of cultural and genetic mixture.

Q3: Do genetic studies provide clear evidence about the Aryans?

Genetic studies reveal layered ancestry in South Asia—local ancient populations mixed with Iran-related and Steppe-related lineages. However, genetics does not identify any group as “Aryan.” It only traces population movements and admixture patterns over time.

Q4: How does this debate influence education and identity today?

The debate shapes school textbooks, social narratives, and identity discussions. Misinterpretations can fuel political or cultural claims, making it essential to teach history using balanced, multi-disciplinary and evidence-based approaches.

Q5: Are the Indus Valley Civilization and Vedic culture the same?

Views differ. Some scholars see cultural continuities between the two, while others consider them distinct traditions. Recent archaeological and genomic findings suggest a complex relationship involving both local developments and external interactions.

References

- Narasimhan, V. M. et al. (2019). The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia. Science. Link

- Reich, D. et al. (2009). Reconstructing Indian Population History. Nature. Link

- Allentoft, M. et al. (2015). Population Genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature. Link

- Basu, A. et al. (2016). Genomic Reconstruction of the History of Extant Populations of India. PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences). Link

- Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Excavation Reports on Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Lothal, Dholavira and Related Sites. Link

- Singh, Upinder. (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. Pearson Education. Link

- Witzel, M. (2001). Early Sources for Vedic Culture. Harvard University Press. Link

- Additional academic articles, excavation summaries and peer-reviewed research papers. Read More