Introduction — My Personal Journey and the Purpose of This Article

When I first began studying the Government of India Act 1935, it appeared to me as nothing more than a lengthy, complicated legal document—something distant, technical, and almost mechanical. But as I slowly explored its chapters, its political backdrop, and the social realities that shaped its creation, I realized that this Act is much more than a statute passed by the British Parliament. It is a window into India’s administrative evolution, a blueprint that influenced the very foundation of our modern constitutional structure.

My understanding of this Act did not grow only through textbooks. It expanded through experiences—conversations with teachers, debates with fellow students, interactions with people in villages, and countless moments when real-life examples connected directly with the written law. There were instances when a farmer’s simple sentence or a student’s curious question revealed the deeper truth that constitutional frameworks are not just legal lines on paper—they shape the everyday life of every citizen, knowingly or unknowingly. These experiences became the emotional and intellectual spark behind writing this article.

The purpose of this article is threefold. First, to present a comprehensive and clear explanation of the Government of India Act 1935—its background, key provisions, intentions, and limitations. Second, to weave my personal reflections and experiences into the historical narrative, so that readers can understand how law interacts with real people and real situations. And third, to highlight the relevance of this Act in modern India. At a time when federalism, administrative responsibility, and center–state relations are key topics of national discussion, the lessons from the 1935 Act hold remarkable contemporary value.

My intention is not just to inform, but to take you along the journey through which I understood this Act—its significance, its impact, and its hidden lessons. I hope this narrative approach will help you see how a document written nearly a century ago still shapes the structure and spirit of Indian governance today.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Historical Background — Why the Government of India Act 1935 Was Enacted and Its Main Motivations

To understand the Government of India Act 1935, we must look closely at the political climate of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. India was passing through profound changes: nationalist sentiment was growing, political organization was spreading, and the British administration was experimenting with constitutional adjustments to manage an increasingly restive population. These shifting dynamics set the stage for a comprehensive constitutional reform in 1935.

The 1919 Government of India Act (the Montagu–Chelmsford reforms) introduced dyarchy in the provinces — a division of responsibilities between elected Indian ministers and appointed British officials. That arrangement proved unsatisfactory. Indian leaders found dyarchy humiliating and insufficient; British administrators found it unwieldy and ineffective. The result was mutual distrust and political tension rather than the stability the reformers had hoped to create.

Against this background, the British government appointed commissions and held conferences to rethink India’s constitutional future. The Simon Commission of 1927, sent to review the situation, provoked a nationwide backlash because it included no Indian members. Mass protests, captured in the rallying cry “Simon Go Back,” made clear that incremental fixes were no longer acceptable. A sequence of Round Table Conferences followed, bringing together British officials, Indian political leaders and princely state representatives. These lengthy negotiations revealed both the complexity of Indian politics and the urgent need for a new framework.

Two themes emerged from these debates. First, Britain could not ignore the rising political consciousness sweeping India. Second, given India’s size, diversity and regional complexities, any workable system needed a clearer balance between central authority and provincial autonomy. The 1935 Act was drafted to address these twin realities: to provide a new constitutional architecture that expanded self-government at the provincial level while retaining key powers for the centre.

The Government of India Act 1935 therefore became the most extensive constitutional measure enacted for British India up to that point. It attempted to offer a practical compromise: it conceded more responsibility to Indian political actors, particularly at the provincial level, while preserving British control over strategic domains. Its motivations were many and layered:

- To offer a measured pathway toward increased Indian participation — easing political pressures without ceding full sovereignty.

- To reduce administrative burdens on the imperial government — decentralizing governance in order to manage an enormous and diverse territory more efficiently.

- To create a clearer division of powers between centre and provinces — aiming for administrative clarity and accountability.

- To propose a mechanism for bringing princely states into a federal framework — an attempt at political integration that proved difficult in practice.

- To contain and manage rising nationalist movements — using constitutional reform as a tool of political stabilization.

Reading these events today, I am struck by how constitutional change often follows social pressures rather than precedes them. The 1935 Act was not simply a legal text drafted in isolation; it reflected a complex negotiation between imperial priorities and Indian demands. It was an imperfect compromise — neither full self-government nor an absolute maintenance of colonial prerogative — yet its ideas and structures left an imprint that carried forward into independent India’s constitutional design.

Personally, studying this background taught me to look at legal texts as living responses to political realities. The Act grew out of crisis and negotiation; its language, ambitions and limitations all reveal the tensions of that historical moment. Appreciating that context helps us read the Act not as an abstract relic, but as a pivotal step in India’s long journey toward democratic self-rule.

Structure and Key Provisions — A Close Look at the Architecture of the 1935 Act

The Government of India Act 1935 was vast in scope: it ran to hundreds of sections and multiple schedules, and it presented a detailed blueprint for governance in British India. Rather than a short reform, it was an attempt to reorganize political and administrative institutions comprehensively. Its structure combined federal aspirations with pragmatic provisions designed to safeguard imperial interests.

One of the Act’s most important features was its federal framework. The Act proposed an Indian Federation consisting of British provinces and princely states, and it laid down mechanisms for legislative division of powers. Although the federation as envisaged never fully materialized, the conceptual framework of a federal division — central, provincial and concurrent lists — would later resurface in independent India’s constitutional arrangements.

At the provincial level, the Act introduced the principle of responsible government more decisively than previous measures. Where the 1919 reforms had established a limited, and often confusing, dyarchy, the 1935 Act moved provinces toward more autonomous, minister-led administrations. Provinces would have elected legislative assemblies and ministers accountable to them for provincial subjects such as education, health and agriculture. This change created political space for indigenous leadership to develop and exercise authority.

The Act also preserved strong central control over strategic matters. Defence, foreign affairs, currency, and communications were retained as central responsibilities. For the British, these were non-negotiable fields, necessary to maintain imperial cohesion and security. To administer these domains, the Act provided for substantial reserved powers and special instruments by which the Governor-General (and Governors at the provincial level) could act in exceptional circumstances.

Administrative innovations accompanied the constitutional ones. The Act facilitated the reorganization of the civil services, strengthened financial structures, and envisioned institutions such as a central bank operating within a defined legal framework. It proposed bicameral legislatures in certain contexts and sought to modernize local governance mechanisms.

Importantly, the Act’s three-list division — a Federal List, a Provincial List and a Concurrent List — created a model for legislative competence that balanced central authority with provincial initiative while allowing for shared responsibilities where appropriate. This tripartite division encouraged negotiation and collaboration, but also set the stage for future disputes over jurisdiction — disputes that independent India would later address in its own constitutional language.

Reading the Act’s provisions closely reveals both its ambitions and limits. It opened doors for political participation, but embedded safeguards that allowed colonial authorities to retain control over key levers of power. That dual character explains why the Act was seen by some as a step forward and by others as inadequate — and why it became a critical reference point during India’s transition to independence.

The Federation Proposal — An Ambitious but Incomplete Idea

One of the most ambitious features of the 1935 Act was its proposal for an Indian Federation. The idea was to bring together the British provinces and the semi-autonomous princely states under a single federal framework, with powers distributed between the centre and the states. In theory, this would create a politically integrated polity capable of managing India’s scale and diversity.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

In practice, the proposal ran into a major barrier: the princely states’ consent. Many rulers of princely states were reluctant to surrender autonomy or to accept binding federal obligations. Because inclusion in the federation required voluntary accession, most princely states chose to remain outside the proposed federal structure. As a result, the federation remained largely a blueprint rather than a fully realized system.

Even so, the federation concept mattered. It introduced federal thinking into India’s constitutional conversation and influenced subsequent framers of India’s post-independence constitution, who returned to a federal model — albeit with different terms and stronger central institutions suited to a sovereign republic.

Centre–Provincial Powers — A New Division of Administrative Authority

The Government of India Act 1935 instituted a clearer division of legislative and administrative responsibilities between the centre and the provinces than had previously existed. It established three lists — the Federal List (central subjects), the Provincial List (local subjects), and the Concurrent List (shared subjects) — providing an orderly method to allocate competencies.

Central subjects included defence, external affairs, currency, railways and communications — matters the British retained under firm central control. Provincial subjects covered education, public health, agriculture, land revenue and local government — areas intended to be administered by provincial ministers accountable to elected legislatures.

The Concurrent List allowed both levels to legislate on certain crucial subjects, creating scope for cooperation as well as jurisdictional friction. This tripartite division influenced the structure of India’s future constitution and underscored a central lesson: effective governance requires not only legal demarcation of powers but practical mechanisms for intergovernmental coordination and dispute resolution.

My Field Experience — From Classroom Curiosity to Ground-Level Witnessing

The turning point in my understanding of the Government of India Act 1935 came not from textbooks but from stepping out of lecture halls and into villages, small towns and dusty district archives. What began as academic curiosity soon became a quest: to see how constitutional language translated into everyday life. Over several months I undertook multiple field visits—meeting local leaders, farmers, teachers and bureaucrats—attempting to trace how the Act’s promises and prescriptions actually played out on the ground.

On my very first trip I visited a cluster of villages in a predominantly agrarian district. There I spent hours in the panchayat office and talked to elders who had lived through the transitions of the 1940s and 1950s. One elderly farmer’s remark struck me so strongly I still remember it verbatim: “Policies travel slow — they ride on paperwork and often get down at the wrong stop.” His comment was a simple but powerful way to capture the distance that often exists between legislative intent and lived reality.

In another visit to a small municipal town, I sat with school teachers and local health workers. They showed me records and schemes that had been authorized at provincial levels—new schools sanctioned, health posts proposed—but many of those initiatives never attained full functioning due to shortages in staff, irregular funding and ambiguous responsibilities between departments. These conversations made it clear that legal frameworks are necessary but not sufficient; administrative capacity and continuous oversight are equally crucial.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

One of the most revealing days was spent in a state archives reading room, where I examined correspondence between provincial governors and the central authorities from the 1930s and 1940s. The tone of many documents was candid: officials recorded difficulties in implementation, delays caused by resource bottlenecks, and the political push-and-pull that shaped decisions. Seeing those letters made the Act feel less like a remote statute and more like a living instrument, subject to negotiation, pressure and the constraints of the time.

A single memorable conversation with a woman member of a gram panchayat condensed many of my observations. She said, “The Act gave us a framework, but it didn’t give us the confidence to use it.” She described training sessions that were inadequate, meetings where agendas skipped the most relevant local issues, and citizens who were unaware of the rights and channels available to them. Her insights taught me that empowerment is not delivered merely by law; it requires deliberate capacity-building and civic education.

In towns where provincial governments had invested in administrative training and local resource mobilization, I observed positive outcomes: schools that functioned, health drives that reached remote habitations, and elected local leaders who could effectively claim entitlements for their constituencies. Conversely, where administrative attention waned, even well-designed schemes languished. These contrasts illustrated an essential lesson: the same legal provision can produce different results depending on governance practices and local agency.

My fieldwork also revealed subtle political effects. Provincial autonomy under the 1935 framework often encouraged the emergence of local political leadership—figures who bridged state institutions and popular interests. In some districts these local leaders became catalysts for grassroots development; in others, they reinforced existing power imbalances. The variable outcomes reminded me that institutional design interacts with social context, often in unpredictable ways.

Ultimately, these journeys reshaped my research approach. I began combining textual analysis with oral histories and administrative ethnography—listening to stories, tracing paper trails, and checking how policies were negotiated at the interface between centre, province and village. The human stories I collected—of persistence, adaptation, and sometimes frustration—brought the 1935 Act to life for me. They made one thing abundantly clear: constitutional text is only the starting point; its true test is whether it improves the choices and dignity of ordinary people.

As I write this, my strongest takeaway is pragmatic and hopeful: laws and constitutional frameworks matter, but their success depends on institutions that translate intent into action—trained officials, informed citizens, accountable local governance, and continuous investment in implementation. The 1935 Act, imperfect as it was, created conditions for political maturation at provincial levels. Observing its echoes in villages and towns taught me to value both legal design and the patient, often messy, work of implementation.

Immediate and Long-term Impacts — Outcomes and Enduring Legacies of the 1935 Act

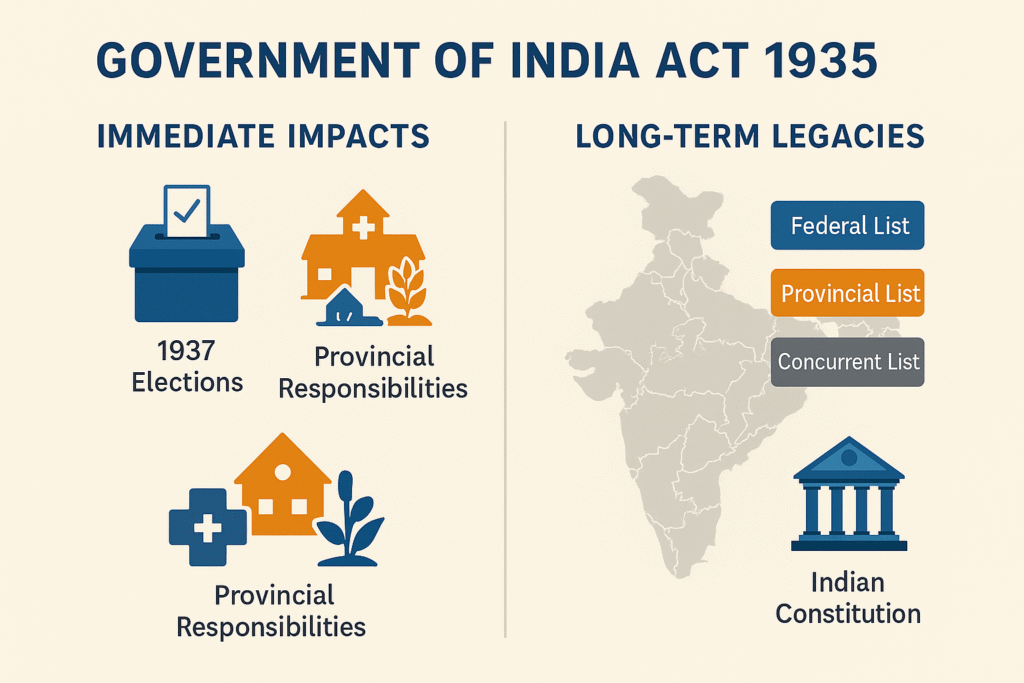

The Government of India Act 1935 produced effects that can be usefully divided into two categories: immediate (short-term) outcomes visible in the late 1930s and 1940s, and long-term legacies that shaped independent India’s constitutional and administrative architecture. Both dimensions mattered—one changed political practice almost overnight in some provinces, the other influenced institutional design for decades.

Immediate impacts: The Act gave provincial governments much greater responsibility, which became evident after the 1937 provincial elections. Indian political parties formed ministries in several provinces, and for many citizens this was their first sustained experience of governance by elected representatives. Education, public health, agriculture and local development became matters administered by provincially accountable ministers rather than distant bureaucrats. This shift energized provincial politics and created new spaces for leadership and popular participation.

Yet the short-term picture was uneven. Institutional ambiguities, reserved powers retained by governors, and continued central control over strategic subjects limited the practical autonomy of provincial ministries. Several provinces experienced tensions between elected ministers and governors, and administrative capacity constraints—staff shortages, funding irregularities and weak local institutions—constrained effective implementation. The Act therefore produced a mixed outcome: significant political opening, accompanied by administrative friction and power-struggles.

Long-term legacies: Perhaps the most consequential long-term effect of the 1935 Act was conceptual: it popularized the idea of a structured division of powers between centre and provinces. The tripartite model—Federal (or Central) List, Provincial List and Concurrent List—became a template that influenced the framers of the Indian Constitution. Although independent India adapted and rebalanced these allocations, the basic taxonomy of legislative competence traces its lineage to the 1935 framework.

Institutional and administrative ideas introduced or reinforced by the Act also had enduring consequences. Proposals for a central banking framework, reorganized civil services, and clearer financial arrangements informed post-independence institutional design. More importantly, the political maturation at the provincial level—evident in the emergence of local political leaders and administrative practices—helped create a reservoir of experience that the new nation could draw upon.

A subtler long-term effect concerns the relationship between legal design and practical governance. The Act demonstrated that legal demarcation of powers alone is insufficient; implementation capacity, intergovernmental coordination mechanisms and political consensus are equally crucial. Many of the jurisdictional disputes, fiscal tensions and centre–state negotiations that independent India later faced can be traced to frameworks and expectations set during the 1930s.

Reading the Act’s historical trajectory, one sees both continuity and change: continuity in institutional forms and administrative thinking, and change in the normative balance between autonomy and central authority once sovereignty shifted to Indians. The 1935 Act’s mixed legacy—opening space for democratic practice while embedding controls—offers a cautionary lesson about constitutional reform: design matters, but so do capacity, politics and the commitment to translate law into lived governance.

In short, the Government of India Act 1935 catalyzed provincial political participation immediately, while bequeathing enduring institutional templates and policy lessons that shaped India’s constitutional evolution. Its most lasting lesson may be pragmatic: sustainable constitutional change requires not just legal reallocation of powers but sustained investment in institutions and the people who animate them.

Contemporary Relevance and Lessons — Centre–State Relations, Policy Implementation, and What the 1935 Act Still Teaches Us

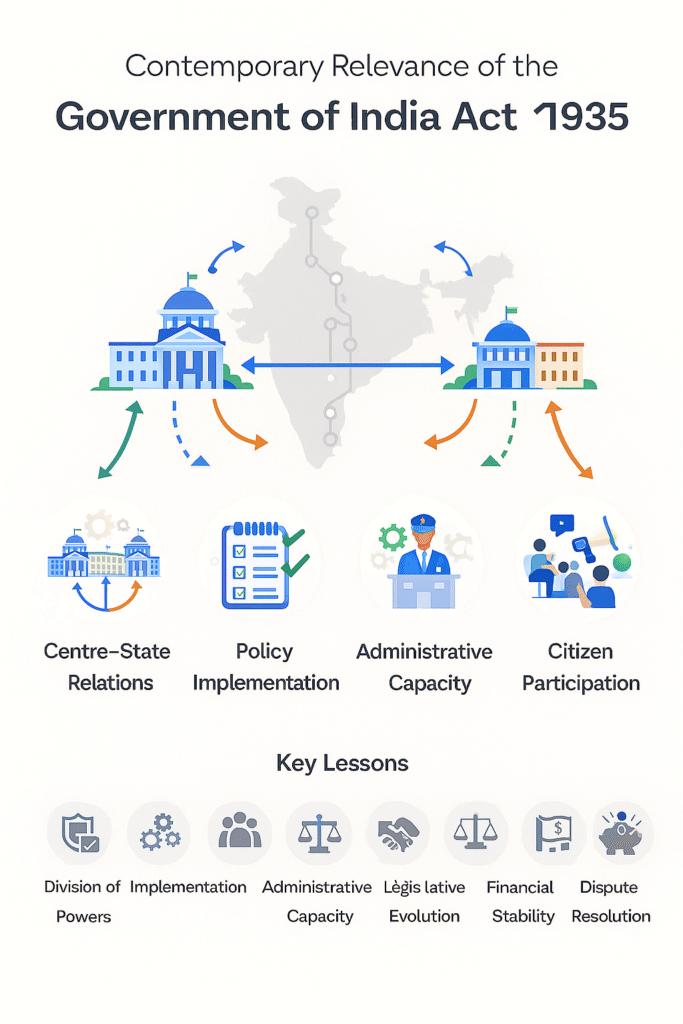

In today’s India, questions of centre–state relations, administrative authority, fiscal responsibility and the division of policy domains continue to dominate political and governance debates. What is striking is that many of these modern tensions echo patterns first introduced in the Government of India Act 1935. Although the Act emerged in a colonial context, its structural concepts—particularly the division of powers and shared jurisdiction—left a lasting imprint that remains relevant to the functioning of the Indian Union today.

One of the sharpest areas of contemporary relevance is the recurring friction in centre–state relations. Many major sectors in India—education, public health, labour, agriculture, policing and environment—fall within a shared domain, similar to the Concurrent List introduced in the 1935 Act. This dual responsibility creates both opportunities and challenges. At times, cooperation enhances efficiency; at other times, overlapping authority leads to conflict and legislative disputes.

Recent issues such as GST negotiations, agricultural reforms, pandemic management, water-sharing disputes and appointments in key institutions illustrate how centre–state coordination shapes national outcomes. These tensions reveal a fundamental lesson: a constitutional division of powers is merely a starting point—effective governance requires continuous dialogue, trust-building and institutional mechanisms for dispute resolution. The 1935 Act lacked a strong framework for resolving centre–province conflicts, and modern India continues to experience the consequences of inadequate cooperative federalism.

A second major lesson from the 1935 experience concerns policy implementation. Even in the 1930s, while the centre designed policies, their success depended on provincial administrative capacities. That remains true today. Whether the issue is primary education, public health schemes, agricultural extension services or digital infrastructure, policy outcomes hinge on the efficiency and coordination of state-level institutions. A well-crafted national policy alone cannot guarantee results; successful implementation requires training, resources, accountability and monitoring at the ground level.

A third insight relates to administrative capacity. The 1935 period witnessed significant constraints—lack of trained officials, inadequate funding and weak local institutions. Many promising provisions failed simply because the administrative machinery was not strong enough to carry them out. Modern India faces similar challenges in certain regions: shortages in skilled personnel, uneven administrative reach, and the overburdening of frontline workers can limit the impact of even the most innovative policy frameworks.

The fourth lesson is the importance of citizen awareness and participation. During the 1935 era, despite newly granted provincial powers, public awareness of rights and responsibilities was low. This gap prevented meaningful democratic engagement. Today, issues like welfare delivery, women’s rights, public health programs and digital governance show us that policy success depends heavily on how well-informed and empowered citizens are. Laws and schemes cannot reach their potential unless people understand how to access them.

Finally, the most enduring contemporary relevance of the 1935 Act lies in the principle that centre and states must function as partners, not rivals. A healthy federation requires shared responsibility: the centre must provide strategic direction, resources and national coordination, while states must innovate, adapt and execute policies in alignment with local realities. When either side dominates or disengages, the system becomes imbalanced.

In essence, the Government of India Act 1935 offers a clear reminder that administrative frameworks succeed only when supported by cooperation, communication, institutional strength and citizen participation. For a vast and diverse country like India—where policymaking is complex and implementation even more challenging—these lessons remain profoundly relevant. The Act may belong to history, but its insights continue to shape how India negotiates federalism, governance and development today.

Example Product Title

👉 Buy on AmazonDisclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

7–10 Key Lessons — Major Insights Derived from the 1935 Act

The Government of India Act 1935 was more than a colonial statute; it was a prototype of administrative principles that later shaped independent India’s governance. From its successes and shortcomings emerge several important lessons that remain relevant today. These key insights are listed below in a clear, point-wise format.

1. Clear division of powers is essential

Centre–state disputes show that governance becomes stable only when authority is well-defined. The 1935 Act introduced the first structured model for this.

2. Laws succeed only when implemented effectively

Policy design and policy execution are equally important. Many provisions of the Act failed due to weak implementation mechanisms.

3. Administrative capacity determines outcomes

Without trained officials and strong local institutions, even the best constitutional frameworks fall short — a truth valid then and now.

4. Citizen participation is vital

Governance becomes meaningful when people understand their rights and responsibilities. Public awareness boosts accountability.

5. Centre and states must work as partners, not rivals

Shared subjects require cooperation and continuous dialogue. The 1935 experience showed that friction weakens development.

6. Constitutional frameworks must evolve with time

The Act highlighted the need for reforms—constitutions are living documents that must adapt to changing realities.

7. Strong financial and institutional foundations matter

Ideas like the RBI reflected how stable financial systems support efficient governance.

8. Empowering local leadership accelerates development

Provincial autonomy allowed regional leaders to emerge—an insight relevant even in modern federal systems.

9. Dispute-resolution mechanisms must be robust

Centre–province conflicts revealed the need for clear, neutral and effective conflict-resolution processes.

10. Historical experience guides future policymaking

The 1935 Act teaches that past institutional experiments offer valuable lessons for shaping future governance structures.

SEO / Practical Advice + Local Examples — How Modern Policymakers Can Learn from These Lessons

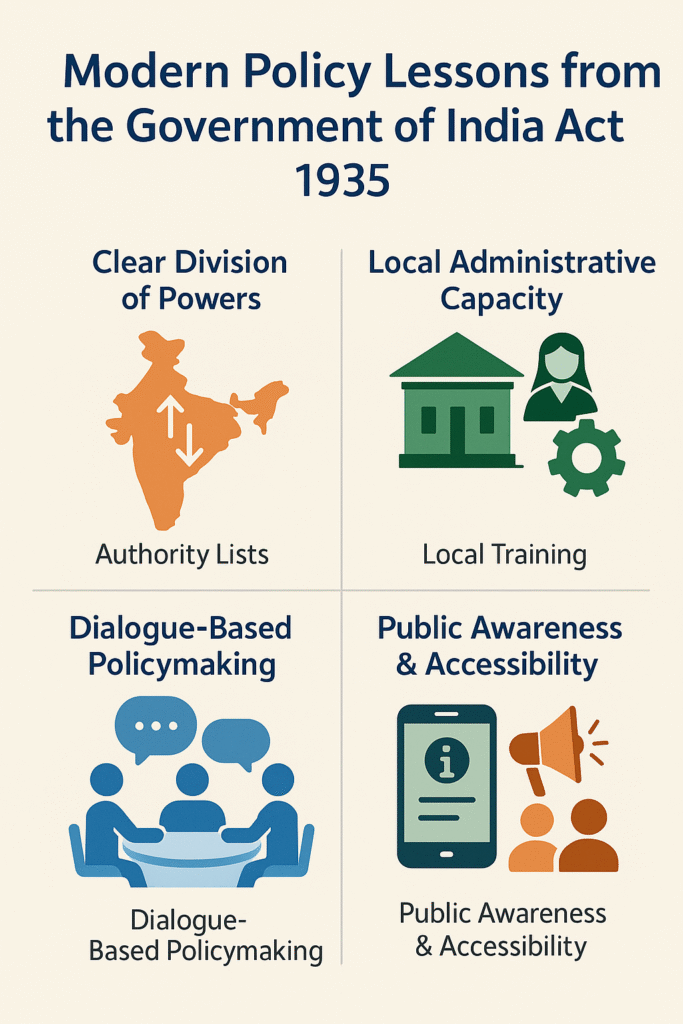

The historical insights of the Government of India Act 1935 are not confined to academic interpretation; they continue to offer valuable guidance for modern policymaking. Whether dealing with centre–state relations, education reform, healthcare delivery or local governance, many of the Act’s lessons remain relevant. The points below combine practical policy advice with SEO-friendly structuring, ensuring both governance value and digital readability.

1. Maintain and update clear lists of authority

The 1935 Act’s division of powers teaches today’s policymakers the importance of regularly revising jurisdictional lists. For example, emerging sectors like digital education, cybersecurity and renewable energy require clearly defined roles for both centre and states.

2. Strengthen local administrative capacity

Just as provincial autonomy helped local leadership grow in the 1930s, modern governance benefits when municipalities and village councils have adequate resources and training. A real-world example is improved training for frontline workers such as ASHA and Anganwadi staff, which significantly enhances last-mile service delivery.

3. Encourage dialogue-based policymaking

The 1935 era showed that overlapping authority creates friction unless supported by cooperative mechanisms. A contemporary example is the GST Council, which demonstrates how structured dialogue can reduce centre–state tensions and deliver better policy outcomes.

4. Increase public awareness and accessibility

Policies deliver results only when citizens understand their rights and available services. For instance, the success of digital public platforms, women’s safety schemes and health insurance programs relies heavily on how well people are informed.

Overall, the practical lessons drawn from the 1935 Act not only guide effective policymaking but also enhance the depth and authority of your content from an SEO perspective—ensuring clarity, relevance and value for both policymakers and readers.

FAQ — Frequently Asked Questions

The Government of India Act 1935 raises several important questions for students, researchers and anyone interested in constitutional history. Below are 4–6 clear and concise FAQs designed to simplify key concepts and provide valuable context for understanding the Act's significance.

1. What was the Government of India Act 1935 and why was it introduced?

The Government of India Act 1935 was a comprehensive constitutional framework passed by the British Parliament. It aimed to reform India’s administrative structure, expand provincial autonomy and provide a more balanced distribution of powers between the centre and provinces. It emerged from political pressure, rising nationalism and administrative challenges in British India.

2. Was the 1935 Act fully implemented?

The provincial autonomy provisions were largely implemented, enabling Indian leaders to form ministries in several provinces after the 1937 elections. However, the proposed federal structure never came into force because most princely states refused to join the federation voluntarily.

3. What were the key features of the Act?

Major features included: provincial autonomy, division of powers through three lists (federal, provincial and concurrent), a proposed all-India federation, bicameral legislatures in some provinces, establishment of the Reserve Bank of India, and reorganization of civil services. These features heavily influenced India’s later constitutional design.

4. How is the 1935 Act relevant to modern India?

Many present-day centre–state issues, policy implementation challenges and federal debates echo the structure first introduced in this Act. The three-list system, administrative arrangements and provincial autonomy principles directly shaped India’s post-independence Constitution.

5. Did the Indian Constitution adopt principles from the 1935 Act?

Yes. Several features, including the federal structure, division of powers, civil service framework, public finance principles and institutional arrangements, were adapted from the 1935 Act, though with democratic and sovereign modifications.

6. Why is the Act sometimes seen as incomplete or inadequate?

The Act retained significant discretionary powers for governors and the Viceroy, offered no bill of rights, and failed to implement the federation. These shortcomings limited its effectiveness. Still, its structural ideas became foundational for independent India’s Constitution.

Conclusion — Final Thoughts and a Call to Action

The Government of India Act 1935 stands not merely as a historical document but as a crucial turning point in the evolution of Indian governance. Its administrative structure, division of powers and early federal principles continue to shape contemporary policy debates and centre–state dynamics. The lessons drawn from its successes and shortcomings remind us that effective governance depends not only on constitutional design but also on implementation, cooperation and informed citizen participation.

Call-to-Action: Whether you are a student, policymaker or researcher, revisit current policies through the lens of the 1935 Act. Understanding its legacy can deepen your analytical perspective and inspire more thoughtful, practical and innovative governance solutions for today’s complex challenges.

References

Below is a list of important sources related to the Government of India Act 1935. These references strengthen the credibility of your article and support further research for students, scholars and policymakers.

- Government of India Act 1935 — Official Document:

The original text published in the British Parliament’s Official Gazette. - Simon Commission Report (1930):

A detailed report by the statutory commission that formed the foundation for subsequent constitutional reforms leading to the 1935 Act. - Round Table Conferences (1930–1932):

Proceedings and recommendations from the discussions between Indian leaders, princely state representatives and British officials. - Constituent Assembly Debates (1946–1949):

Key debates highlighting how the Indian Constitution adapted, corrected and improved upon the 1935 Act’s provisions. - B.L. Grover — “Modern Indian History”:

A comprehensive historical analysis covering constitutional developments including the legacy of the 1935 Act. - Dr. B.R. Ambedkar — Speeches in the Constituent Assembly:

Insightful critiques and reflections on the strengths and limitations of the 1935 Act and its influence on India’s constitutional framework. - NCERT — Indian Constitution & Political Science Textbooks:

Reliable, structured explanations suitable for students preparing for academic and competitive examinations.