Introduction

History often feels distant, like a collection of events that happened in another world, to people we never knew. But the truth is this: history becomes alive only when it touches us personally—when it sparks curiosity, raises questions, or inspires us to look deeper. My connection to the Government of India Act 1919, also known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, began in a surprisingly simple moment on a quiet afternoon. I was going through my grandfather’s old wooden trunk, filled with his college notebooks, worn-out papers, and fading ink. Among those fragile, yellowed pages, I found his notes on the “Dyarchy System.” It was the first time I had encountered the term, and something about it stayed with me.

My grandfather often told me that the year 1919 was not just a date in the timeline of British India. It was a turning point—a moment when political consciousness in India was rising rapidly, and the demand for rights, voice, and representation was becoming impossible for the British Empire to ignore. For him, the Government of India Act 1919 represented a delicate balance between hope and disappointment. It was the first time Indians were given a share in governing their own provinces, but the power was limited, divided, and tightly controlled. Yet, he believed it marked the beginning of something bigger: India’s journey toward self-rule.

When we study this Act today, it becomes clear that it was more than a constitutional reform. It was a statement—an acknowledgment that India could no longer be governed by old colonial methods. Through these reforms, the British introduced the concept of “dyarchy,” expanded legislative councils, widened limited forms of franchise, and for the first time formally committed to the gradual development of responsible government in India. But this story is not only about progress; it is also about contradictions. Just like many reforms in history, the 1919 Act was welcomed and criticized at the same time. It promised change but delivered it slowly. It inspired hope but also triggered frustration.

In this article, I am not merely presenting facts. I am taking you through a journey—interwoven with personal reflection, historical context, and lessons that remain relevant even today. This is the story of reforms that shaped India’s constitutional evolution, long before the country became independent. It is the story of how people, in a time of uncertainty, began to believe that transformation was possible. And above all, it is the story of why incremental changes, no matter how imperfect, can create the foundation for future revolutions.

Why This Topic Still Matters Today

The Government of India Act 1919 reminds us that democracy is not a sudden achievement—it is a gradual journey. It teaches us that even partial reforms can ignite movements, strengthen political awareness, and sow the seeds of future change. Most importantly, it helps us understand that the history of India’s democratic evolution is not just a story of the past but a foundation for the nation we live in today.

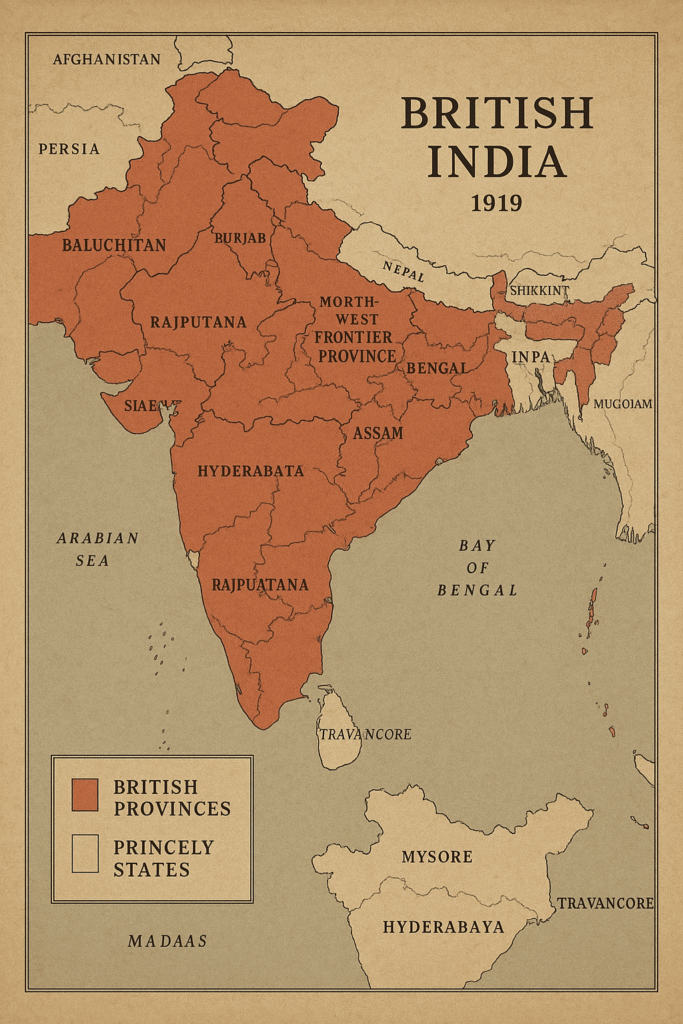

Historical Background

To understand the Government of India Act 1919 (also known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms), we must step back into the political and global climate of the early 20th century. The year 1919 was not merely a date on a constitutional timeline; it marked a turning point in India’s struggle for political rights, self-governance, and national identity. The Act did not emerge in isolation—it was shaped by war, rising nationalism, political negotiations, and the changing priorities of the British Empire. Each of these forces pushed the British government closer to reforms that it had resisted for decades.

The Impact of the First World War

The First World War (1914–1918) dramatically altered the political dynamics between Britain and India. The British Empire relied heavily on India’s manpower, resources, and financial support. More than 1.3 million Indian soldiers fought for the Empire, and countless others contributed through labor, supplies, and economic aid. This participation strengthened India's moral claim for political rights. Indian leaders believed that such sacrifices entitled the nation to a more meaningful role in governance.

By the end of the war, a new wave of political consciousness swept across India. People had developed a stronger belief that change was possible, and that India’s loyalty should be rewarded with greater autonomy. The British administration also sensed that ignoring these expectations would only intensify unrest. Across the globe, democratic ideas were gaining strength, and colonial subjects were demanding representation. The Empire could no longer rely solely on old administrative methods.

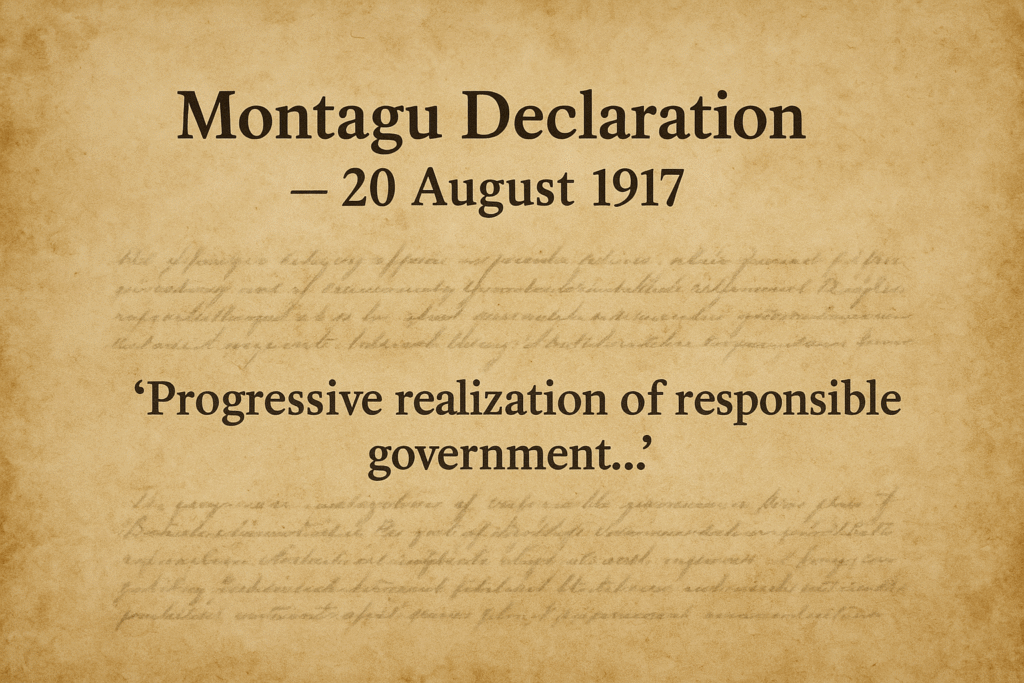

The Montagu Declaration, 1917

In response to growing pressure, the British Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, made a historic declaration on 20 August 1917. Known as the Montagu Declaration, it publicly committed Britain to the gradual introduction of responsible government in India. The declaration stated:

“The progressive realization of responsible government in India is the goal of British policy.”

This was the first time Britain officially acknowledged that Indians would be allowed to participate more meaningfully in governing their own country. Although the vow was vague and carefully worded, it created a powerful psychological shift. Indian leaders saw it as a milestone, while the masses viewed it as a symbolic acceptance of their growing political aspirations.

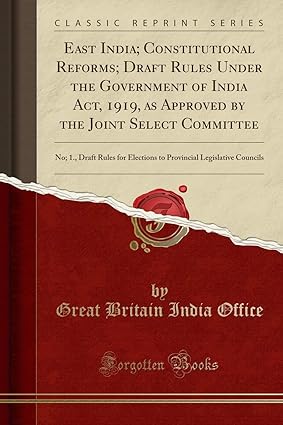

The Montagu–Chelmsford Report, 1918

To translate the declaration into a practical framework, Montagu and the Viceroy of India, LORD Chelmsford, undertook a detailed study of India’s administrative needs. Their findings were published in the Montagu–Chelmsford Report of 1918. This report outlined a new political structure designed to give Indians limited responsibility while retaining British control over key areas.

- It proposed “dyarchy” in provinces—a system where power would be divided between British officials and Indian ministers.

- It suggested expanding legislative councils and introducing a broader, though still restricted, franchise.

- It recommended greater provincial autonomy while keeping the central government firmly under British rule.

The report generated intense debate. Moderate leaders considered it a meaningful step toward self-governance, while more radical nationalists criticized it as insufficient and symbolic. Nevertheless, it laid the foundation for the Government of India Act 1919.

Pressure from the Indian National Movement

Behind the reforms was the steady rise of Indian nationalism. Between 1885 and 1915, the Indian National Congress evolved from a platform of polite petitions to a strong political voice demanding structural changes. Movements led by leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Annie Besant’s Home Rule Movement, and widespread protests against the partition of Bengal demonstrated that Indians were no longer passive subjects. They were politically aware citizens willing to fight for their rights.

The masses had begun to realize that sustained pressure and organized movements could force the British government to respond. This awakening made it clear that the Empire needed to introduce reforms—not out of generosity, but out of necessity—to prevent political instability and maintain its control.

Conclusion: Forces That Shaped the Act

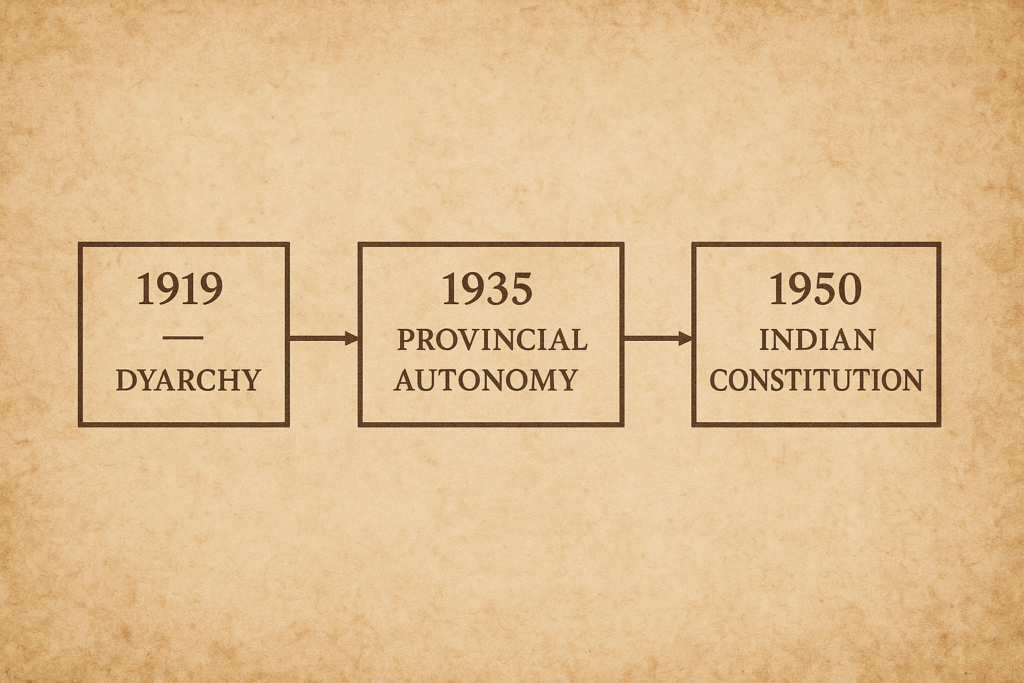

The Government of India Act 1919 was not the product of goodwill alone. It emerged from a combination of global events, wartime contributions, domestic political pressure, and a growing awareness among British officials that India could not be governed without reform. Although the Act fell short of Indian expectations, it marked an important moment in the country’s constitutional journey. It reflected both the possibilities and limitations of colonial reform and set the stage for the larger constitutional shifts that would follow, including the Act of 1935 and ultimately the framing of India’s own Constitution.

Main Provisions and Administrative Structure

The Government of India Act 1919, commonly known as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, played a crucial role in reshaping India's constitutional and administrative framework. It emerged at a time when political awareness, mass movements, and pressure for self-governance were rapidly increasing across the country. The reforms attempted to strike a balance between British control and Indian participation, although the outcome remained limited and controversial. In this section, we explore the major provisions and structural changes introduced by the Act in a detailed and systematic manner.

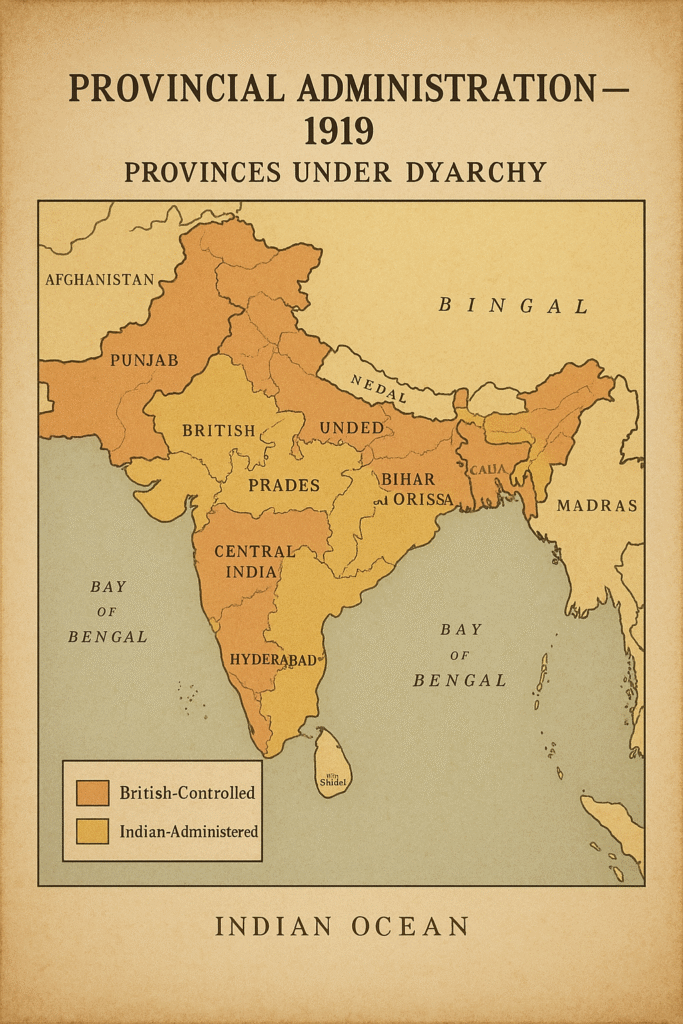

1. Introduction of Dyarchy in Provincial Administration

The most significant feature of the Act was the introduction of Dyarchy (dual administration) in the provinces. Dyarchy divided provincial subjects into two categories, each assigned to different authorities:

- Reserved Subjects: Controlled exclusively by the Governor and his executive council (mostly British officials).

- Transferred Subjects: Managed by Indian ministers who were responsible to the legislative councils.

Reserved Subjects (Under British Control)

- Finance and Revenue

- Law and Order (Police)

- Irrigation

- Land Revenue and Excise

- Home Department and Justice

Transferred Subjects (Under Indian Ministers)

- Education

- Public Health

- Local Self-Government

- Agriculture and Industries

- Public Works (excluding strategic areas)

Although Indian ministers were given charge of transferred subjects, their authority was limited. The provincial Governor retained overriding powers, including the right to veto decisions, withdraw portfolios, or intervene in the name of “public interest.” This dual structure often created confusion, friction, and administrative delays, exposing the contradictions inherent in dyarchy.

2. Changes in Provincial Legislature

The Act expanded the provincial legislative councils and increased the number of elected Indian members. In some provinces, elected members constituted nearly 70% of the council. Indian ministers were appointed from among these elected members and were accountable to the legislature for transferred subjects.

However, the Governor remained the central authority. Even though the councils gained some autonomy, the Governor’s discretionary and emergency powers meant that real authority still rested with the British.

3. Central Government Structure

While the Act introduced major changes in provinces, the central government remained under firm British control. Real power continued to be exercised by the Governor-General and his executive council.

- The Act introduced a Bicameral Legislature at the center.

- The two houses were the Legislative Assembly and the Council of State.

- However, both bodies had severely restricted powers.

The Governor-General retained:

- Absolute veto power over legislative decisions

- Authority to enact ordinances

- Control over defense, foreign affairs, and major financial matters

Thus, despite structural expansion, Indians remained largely excluded from central decision-making.

4. Expansion of Franchise (Voting Rights)

The 1919 Act introduced a limited but significant extension of voting rights in India. For the first time, a large number of Indians were able to vote, although the eligibility criteria restricted participation severely.

Franchise was based on:

- Property ownership

- Education

- Income level

- Tax payment

As a result, only about 3% of the Indian population gained the right to vote. Even though the number was extremely small, it contributed to growing political awareness and the spread of electoral practices across the country.

5. Public Service and Recruitment Reforms

The Act made provisions for expanding Indian participation in higher administrative services. It recognized that Indians should gradually be admitted to the Indian Civil Service (ICS) and other executive positions. Although the actual implementation remained slow, this marked an important ideological shift from earlier policies that had kept top roles almost entirely British.

6. Creation of New Institutions and Commissions

To support administrative reforms, the Act introduced:

- The Public Service Commission — for supervising recruitment and regulating civil service examinations.

- The Finance Committee — for reviewing provincial expenditures and coordinating financial matters.

These bodies laid the foundation for future constitutional institutions that would play central roles in modern India.

7. Deficiencies and Structural Limitations

Despite its reformist appearance, the Act suffered from multiple weaknesses:

- The Governor and Governor-General retained excessive discretionary powers.

- Dyarchy proved inefficient and confusing in practice.

- The central government remained almost fully under British control.

- Voting rights were limited to a privileged minority.

- The reforms did not satisfy Indian demands for real self-government.

These limitations fueled further dissatisfaction, ultimately strengthening the freedom movement and creating momentum for more significant reforms.

Overall Assessment

In essence, the Government of India Act 1919 was a transitional reform — neither fully democratic nor completely autocratic. It marked the beginning of structured political participation for Indians, laid the groundwork for provincial autonomy, and introduced constitutional practices that would evolve further in 1935 and beyond. The Act’s biggest contribution was not the power it granted, but the political debate and national awakening it triggered.

Implementation and Immediate Reactions

After the Government of India Act, 1919 became law, its provisions moved from statute books into practice—but the transition was neither smooth nor uniform. The Act required administrative reorganization at both the centre and the provinces, the creation of electoral rolls, the formation of new ministerial offices, and adjustments within the colonial bureaucracy. Implementation therefore involved a mix of legal, institutional and political steps that revealed both the potential and the limits of the reforms.

How the Act was Rolled Out

Implementation began with the expansion of legislative councils and the drawing up of electoral rolls based on the new, restricted franchise. Provincial elections were organized to populate these councils; elected members then formed ministries to handle the “transferred” subjects. Administratively, British officials redefined departmental responsibilities so that Indian ministers could take charge of portfolios like education, public health and local self-government. At the centre, a bicameral legislature was instituted, though central powers remained tightly guarded by the Governor-General and his executive council.

Administrative Frictions and Practical Difficulties

The twin-track system of dyarchy quickly produced practical problems. The division between “reserved” and “transferred” subjects was often ambiguous: many policies cut across categories (for example, health programmes that required finance approvals), provoking jurisdictional disputes. Governors retained wide discretionary and emergency powers, including veto authority and the right to suspend ministries—measures that undercut ministerial initiative. Senior British officials were sometimes reluctant to accept Indian political leadership, and bureaucratic inertia slowed reforms. As a result, coordination between elected ministers and colonial administrators was frequently strained, and policy implementation suffered delays.

Political Reactions: Moderates, Extremists and Regional Forces

Political responses were mixed and quickly partisan. Moderate nationalists welcomed the Act as a cautious but positive step toward responsible government—an opening that could be widened through negotiation. Many provincial leaders accepted ministerial roles and sought to demonstrate administrative competence. However, more assertive nationalists and younger activists criticized the Act as inadequate and tokenistic. They argued that the reforms preserved ultimate British control while giving the appearance of power-sharing. In several provinces—most notably Bengal, Madras and Punjab—local leaders used newly formed councils to press specific regional demands, but also publicly expressed frustration at structural constraints.

Public Reception and Social Impact

Among the public, reactions varied by class, region and education. Urban, educated classes who gained franchise rights became more politically mobilized, participating in elections, forming local branches of national parties, and engaging in public debate. Rural and less-educated populations, excluded by property and tax qualifications, experienced little immediate benefit. In some areas, incremental improvements in local administration (roads, sanitation, schools) produced goodwill; in others, the visible limits of ministerial power caused disappointment and cynicism.

Consequences for the National Movement

Importantly, the Act’s limited concessions sharpened rather than satisfied nationalist demands. The failure of dyarchy to deliver meaningful power to Indian leaders convinced many that constitutional negotiation alone might not achieve full self-government. This realization contributed to renewed activism and helped pave the way for mass movements of the 1920s—most prominently the Non-Cooperation Movement—by convincing leaders and the public that greater pressure, not mere petitions, would be necessary to secure real political authority.

Summary

In short, implementation of the 1919 Act was a pragmatic experiment that exposed the tensions of colonial reform: it created new spaces for Indian political participation while retaining British mechanisms of control. Administrative confusion, uneven public benefits, and political disappointment highlighted the reform’s limits, even as the experience of governance and electoral politics contributed to India’s broader journey toward self-rule.

Impact — Short-term and Long-term Consequences

The Government of India Act, 1919 (the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms) produced a complex legacy. It was immediately consequential in administrative and political terms, and its longer ripple effects shaped constitutional development, political culture, and the trajectory of the Indian national movement. Below we separate the Act’s main short-term outcomes from the deeper, long-term consequences that followed over decades.

Short-term (Immediate) Impacts

1. Increased Indian participation at provincial level

One clear immediate effect was the entry of Indian ministers into provincial governments for the first time on a meaningful scale. Transferred subjects—education, local self-government, public health and agrarian improvement—came under the responsibility of elected Indian ministers. This created new portals for political actors to demonstrate governance capability, and brought administration closer to local concerns.

2. Expansion of electoral politics and public engagement

Though franchise remained limited, the expansion of legislative councils and the holding of more elections energized political life. Provincial campaigns, electoral mobilization, and the growth of local party organizations accelerated political socialization. Public debates in assemblies introduced practices—parliamentary procedure, opposition scrutiny, constituency politics—that formed the bedrock of later democratic life.

3. Administrative confusion and practical frictions

The dyarchy system produced immediate administrative difficulties. The division between “reserved” and “transferred” subjects frequently blurred in practice, creating jurisdictional disputes between governors and Indian ministers. Governors’ overriding powers and the ability to veto or suspend ministerial decisions undermined cooperative governance and caused delays or policy paralysis in several provinces.

4. Disappointment among nationalists and renewed agitation

For many nationalists the Act proved deeply unsatisfactory. The limited nature of reforms, the retention of key powers by the British executive, and the continuing restrictions on franchise convinced large sections that constitutional negotiation alone would not deliver full self-government. This disappointment helped fuel more assertive political movements and campaigns in the immediate post-1919 years.

Long-term (Structural and Political) Consequences

1. Institutional and constitutional groundwork

The Act’s greatest long-term contribution was institutional. It normalized the idea of representative institutions and provincial responsibility, thereby creating constitutional precedents. Administrative bodies—such as early public service commissions and financial arrangements between center and provinces—began to take shape. These institutional seeds later matured into formal structures under the Government of India Act 1935 and ultimately influenced the framers of the Indian Constitution.

2. Evolution of centre-state relations

By formally distinguishing provincial and central responsibilities, the Act initiated a sustained debate over federalism in India. Questions about the distribution of fiscal authority, administrative competence, and emergency powers did not vanish—they evolved. The dyarchy experience informed later reforms when architects sought clearer and more workable arrangements for centre-state relations.

3. Political maturation and democratic practice

Even with restricted franchise, the electoral experience after 1919 trained a generation of politicians and voters. Legislative debates, party organization, constituency service, and public accountability became part of political life. This political maturation made mass democratic mobilization and eventual transition to full adult suffrage more practicable in the 1940s and after independence.

4. Catalyzing greater demands for self-rule

Paradoxically, the Act’s partial concessions sharpened nationalist demands. The limited nature of the reforms clarified what was missing and concentrated political energy around fuller self-government. Movements that followed used both the new institutions and extraparliamentary tactics to press for more radical change, contributing to the momentum that produced the larger constitutional shifts of the 1930s and the independence movement of the 1940s.

5. Mixed legacy for administrative professionalism

The Act acknowledged Indian participation in higher services and laid the conceptual groundwork for merit-based recruitment and service commissions. Over the long run, these developments supported the creation of a professional civil service in independent India, even as earlier colonial patterns of hierarchy and central control persisted in modified form.

Overall Assessment

The Government of India Act 1919 must be judged as transitional rather than transformational. In the short term it opened doors—new ministers, more elected representation, and wider public engagement—but it also created pitfalls—administrative ambiguity and political frustration. In the long term, however, the Act’s real significance lies in the institutional and normative precedents it established: the normalization of provincial responsibility, the spread of electoral politics, and the sharpening of demands for full sovereignty. Its mixed inheritance—neither full emancipation nor simple continuity—helped shape India’s constitutional journey and the modern political practices that followed.

My Personal Stories — Anecdotes and Lessons

History becomes meaningful when it touches our personal lives — when a faded document, a classroom debate, or a small field visit changes the way we see the past. In this section I share three personal anecdotes that shaped my understanding of the Government of India Act 1919 and the Montagu–Chelmsford reforms. Each story is followed by clear lessons so readers can draw practical insights rather than merely consume facts.

Story 1: A Trunk, a Note, and a Question

The first time the word “dyarchy” entered my life it came from an unlikely place — a battered wooden trunk in my grandfather’s attic. Among yellowing newspapers and college notebooks I found a hand-written marginalia where he had jotted down his impressions of provincial councils in the 1920s. He wrote, almost in passing, about a local minister who “tried to run schools but couldn’t without the treasury’s permission.” That small note pulled me into months of reading and research. What seemed like a technical term in a textbook suddenly had faces, frustrations, and real consequences attached to it.

Lesson 1

Personal artifacts humanize constitutional history. A technical reform like dyarchy stops being abstract when you trace its effects on real people and institutions. When teaching or writing history, seek out those human traces — letters, notebooks, and oral memories — because they convert sterile clauses into living experience.

Story 2: The College Debate That Broke My Certainties

During my university years I participated in a heated debate: “Was the 1919 Act a meaningful step towards self-government or merely tokenistic?” I entered confident that the reforms were inadequate; I left with a more nuanced view. One peer argued convincingly that administrative exposure to representative responsibility trained local leaders in governance; another showed how governors’ vetoes made many ministerial initiatives symbolic. Listening to both made me realize that historical judgments require balancing short-term efficacy against long-term institutional learning.

Lesson 2

Avoid binary conclusions. Reforms can be simultaneously flawed and formative. A helpful approach is to evaluate both immediate outcomes and latent capacities developed by reforms — the lessons in governance, the skill-building, and the precedents that later actors build upon.

Story 3: A Field Visit to a Provincial Archive

For a research project I spent a week in a small provincial archive examining council minutes from the early 1920s. Reading hand-written resolutions, I found instances where local ministers expanded primary schools, negotiated with village bodies, and piloted sanitation schemes. Most of these programs stalled because finance remained under the Governor’s control. Yet where local officials, NGOs, and community leaders collaborated, modest improvements endured. The record showed two truths simultaneously: institutional constraints limited scope, and local initiative often found ways to produce tangible gains.

Lesson 3

Policy design and policy implementation are separate challenges. Constitutional reforms matter, but without fiscal devolution, administrative capacity, and community engagement, their impact will be truncated. Practical change follows where legal openings are matched with financial autonomy and grassroots partnership.

Reflections — What These Stories Teach Us

Taken together, these anecdotes shape a balanced interpretation. The Government of India Act 1919 was neither a full victory for self-rule nor an outright charade. Instead, it was a transitional experiment that opened institutional spaces while maintaining colonial controls. Its real significance often lay in what it enabled indirectly — the training of political actors, the normalization of representative forums, and the creation of administrative practices that later generations could expand or contest.

Practical Takeaways (Actionable Lessons)

- Combine archival and oral sources: To understand constitutional change, pair law-texts with lived experiences — letters, minutes, and testimonies reveal the human consequences of reforms.

- Evaluate reforms on two horizons: Judge both the immediate policy effects (did people’s lives improve?) and the latent institutional learning (did governance skills and norms develop?).

- Focus on implementation capacity: Constitutional openings require administrative training, fiscal space, and civic engagement to translate into outcomes.

- Use local case studies: Small-scale provincial experiments often provide more practical insights than national summaries; they show how constraints are negotiated on the ground.

- Encourage balanced debate: In classrooms and public forums, avoid polarized readings. Encourage students and citizens to analyze reforms both critically and sympathetically.

These stories also carry a personal conviction: history is a guide for policy makers and citizens alike. When we study reforms like the 1919 Act through the dual lenses of institutional design and lived experience, we learn how to craft better transitions in our own time — whether the subject is decentralization, civil service reform or civic education. The past thus becomes a practical toolkit rather than a museum exhibit.

Critique and Appraisal

The Government of India Act, 1919 is best understood as a transitional experiment rather than a conclusive reform. While it introduced important institutional innovations, it was simultaneously constrained by structural limits that curtailed genuine self-rule. Below are the principal criticisms historians and contemporaries have raised, followed by a concise appraisal of the Act’s weaknesses.

1. The Incomplete Nature of Dyarchy

Dyarchy divided provincial responsibilities into “reserved” and “transferred” subjects, but the division proved ambiguous and often dysfunctional in practice. Ministers responsible for transferred subjects lacked effective control over finance and faced the governor’s overriding authority. The result was partial responsibility without commensurate power—an arrangement that produced confusion, friction and limited accountability.

2. Excessive Executive Powers at Centre and Province

The Governor-General and provincial governors retained sweeping discretionary, veto and ordinance-making powers. These powers effectively subordinated elected ministries and legislative bodies, undermining the democratic legitimacy of representative institutions and maintaining the colonial executive’s supremacy.

3. Restricted Franchise and Elite Representation

The extension of the franchise was limited by property, tax and education qualifications. Only a small fraction of the population gained voting rights, leading to a legislature that remained skewed towards propertied, urban and literate classes. This restricted representative base limited the social legitimacy and reach of provincial governments.

4. Ambiguity of Intent — Reform or Containment?

Critics argue that the Act reflected contradictory imperial aims: on paper it promised “progressive realization” of responsible government, but in practice it was designed to contain political demands and preserve imperial control. The mixed intentions produced reforms that were symbolically significant but substantively cautious.

5. Uneven Regional and Social Impact

The Act’s effects varied widely across provinces and social groups. Urban provinces with stronger political organizations derived more benefit; many rural and marginalized communities remained effectively excluded. The uneven rollout highlighted the limits of top-down constitutional tinkering without parallel capacity-building on the ground.

Appraisal — Why These Criticisms Matter

Taken together, these criticisms explain why the Act failed to satisfy major nationalist demands. It created institutional openings but refused to relinquish decisive power. The result was increased political mobilization and agitation rather than placation—demonstrating that partial concessions, if not accompanied by real empowerment, can intensify demands for fuller change.

Modern Lessons — What Policymakers and Citizens Should Learn

The 1919 reforms offer several enduring lessons for contemporary governance and constitutional reform. These insights are relevant for any process that seeks to transfer power, build institutions, or expand democratic participation.

Lesson 1: Empowerment Requires Both Authority and Capacity

Delegating responsibility without corresponding financial and administrative authority produces tokenism. Successful decentralization requires fiscal devolution, human-capital development, and institutional support so local actors can deliver results.

Lesson 2: Transparency and Accountability Compensate for Power Imbalances

Where asymmetric powers remain (for historical or practical reasons), transparent procedures and independent oversight mechanisms (audit, ombudsman, public service commissions) are crucial to ensure accountability and public trust.

Lesson 3: Pilot Reforms, Monitor Outcomes, Scale Carefully

Small-scale experiments—properly monitored and evaluated—can reveal practical obstacles and success factors. Learning from provincial or municipal pilots helps design more robust nationwide reforms.

Lesson 4: Inclusive Franchise Strengthens Legitimacy

Expanding participation beyond elite groups is central to democratic legitimacy. Inclusive suffrage and representative mechanisms help align public policy with popular needs and reduce social alienation.

Lesson 5: Constitutional Change Must Be Complemented by Civic Capacity

Legal reforms mean little without civic education, administrative professionalism and participatory institutions. Building these capacities should be an explicit component of any reform agenda.

Policy Implications

- Design fiscal federalism with clear revenue-sharing rules and predictable transfers.

- Invest in administrative training and independent institutions (audits, PSCs) to support decentralization.

- Use pilot programs with rigorous evaluation before national rollout.

- Promote civic education to expand political participation and accountability.

- Ensure legal reforms include timelines and safeguards for genuine power transfer.

Conclusion

The Government of India Act 1919 stands as a defining “transitional moment” in India’s constitutional history. It neither granted full self-government nor preserved the old colonial structure unchanged. Instead, it created a hybrid model that opened limited spaces for Indian participation while retaining decisive powers within the British executive. Its immediate effects were mixed, but its long-term significance lies in the institutional habits, political awareness and administrative practices it helped shape.

The greatest contribution of the Act was not the authority it offered but the precedents it set. Dyarchy may have faltered in practice, yet it normalized the idea that governance must be shared and that Indians deserved a role in public administration. The reforms highlighted the core truth that constitutional progress depends as much on capacity, resources and implementation as on legislative design.

For modern readers and policymakers, the lesson is clear: power transfer is meaningful only when paired with genuine autonomy, accountability and institutional readiness. Small reforms and experimental models can open the door to larger transitions, but they require transparency, civic participation and long-term commitment to succeed.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What was the Government of India Act 1919?

The Government of India Act 1919 (Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms) was a constitutional reform enacted by the British Parliament that introduced dyarchy in provincial governments, expanded legislative councils, and extended a limited franchise. It aimed to initiate a gradual transfer of administrative responsibilities to Indian representatives while retaining key powers with the British executive.

2. What is “dyarchy”?

Dyarchy (dual government) divided provincial subjects into reserved and transferred categories. Reserved subjects (e.g., finance, law & order) remained under the governor’s control, while transferred subjects (e.g., education, public health) were administered by ministers responsible to provincial legislatures.

3. Did the Act grant India self-government?

No. The 1919 Act provided limited provincial self-government but stopped short of full self-rule. Central powers—defense, foreign affairs and major financial controls—remained firmly under British control, and provincial governors retained overriding authority.

4. How did the Act change voting rights?

The Act expanded the franchise compared with earlier arrangements, but voting remained highly restricted by property, income, tax and educational qualifications. Only a small percentage of the population (roughly a few percent) became eligible to vote.

5. What were the main criticisms of the Act?

Key criticisms included the incomplete nature of dyarchy, excessive powers of governors and the Governor-General (veto and ordinance powers), limited franchise that favored elites, and the Act’s tendency to contain nationalist demands rather than meet them.

6. How did political parties and leaders react?

Reactions were mixed: moderates considered the Act a cautious step toward responsible government, while many nationalists saw it as inadequate and tokenistic. The limitations of the Act contributed to greater agitation and helped fuel mass movements in the 1920s.

7. What institutional changes did the Act introduce?

The Act expanded legislative councils, created a bicameral central legislature (Legislative Assembly and Council of State), and encouraged institutional mechanisms such as early public service commissions and financial review bodies—foundations for later constitutional developments.

8. Why does the Act matter today?

The Act matters as a transitional milestone: it normalized representative governance at the provincial level, initiated debates on centre–state relations and fiscal authority, and offered lessons on how partial reforms can both enable and frustrate democratic development.

9. Where can I read primary sources?

Primary sources include the Montagu–Chelmsford Report (1918) and the full text of the Government of India Act 1919. These are available in national archives, university libraries, and many digital repositories such as the Internet Archive or library collections.

10. Further reading suggestions?

For concise context, consult modern histories of colonial India and works on constitutional development by historians like Bipan Chandra and Granville Austin. Scholarly articles on dyarchy and provincial politics provide deeper, region-specific insights.

References

The sources listed below provide reliable and in-depth information on the Government of India Act 1919, the Montagu–Chelmsford Report, and the wider political context of early 20th-century India. These references are useful for academic research, article writing, and deeper historical study.

- Montagu–Chelmsford Report (1918)

The original British government report that formed the basis of the 1919 constitutional reforms. - Government of India Act, 1919 — Official Text

The full legal document containing all constitutional provisions, administrative structures and legislative procedures. - Constitutional History of India (Academic Books)

Works by prominent historians such as Bipan Chandra, Granville Austin, Judith Brown and Ramachandra Guha, offering detailed analysis of India’s constitutional evolution. - Research Papers on the Indian National Movement

Scholarly articles exploring the political climate, debates, and nationalist responses surrounding the 1919 reforms. - Provincial Legislative Records (1920–1930)

Minutes, proceedings and archival documents from provincial councils that reveal the practical functioning of dyarchy. - Modern Histories of Colonial India

Books and academic works examining British policies, administrative reforms and the socio-political impact of colonial governance. - Studies on Indian Administrative Institutions

Literature on the evolution of the Indian Civil Service, Public Service Commissions, and fiscal frameworks shaped by the 1919 reforms.