Major Mountain Ranges of the Himalayas: Geography, Culture and Natural Wonders

Introduction — Why the Himalayas Are More Than Just Mountains

The Himalayas are not merely a chain of towering peaks; they are a living, breathing universe of their own. When most people hear the word “Himalaya,” they imagine snow-covered summits, icy winds, and rugged cliffs. But the truth is much deeper. The Himalayas are a vast ecological, cultural, and spiritual system that stretches across five nations, shaping the climate, biodiversity, rivers, and lives of millions of people. Their story is not just about geography; it is about humanity’s bond with nature.

Extending for nearly 2,400 kilometers, this colossal mountain system stands as the natural shield of the Indian subcontinent — from the Karakoram and Jammu & Kashmir in the west to the lush valleys of Arunachal Pradesh in the east. Every valley, every glacier, and every ridge holds centuries of legends, scientific mysteries, and cultural heritage. Standing before these mountains, one cannot help but feel humbled — as though time itself slows down in their presence.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

My first visit to the Himalayan foothills changed my perception of nature forever. The air felt different — lighter yet more profound, as if carrying ancient stories from the peaks. The rivers roared like living veins of the Earth, and the forests whispered truths older than civilizations. Conversations with local communities revealed something powerful: to them, the Himalayas are not just a landscape, but a guardian, a teacher, and a deeply spiritual companion.

Scientifically, the Himalayas are one of the youngest yet most significant fold-mountain systems on Earth. They are the birthplace of major Asian rivers such as the Ganga, Indus, and Brahmaputra — earning them the title “Water Tower of Asia.” Without the Himalayas, the climate, agriculture, water supply, and biodiversity of large parts of the continent would collapse. They influence monsoons, host thousands of plant and animal species, and protect the plains from harsh cold winds.

At the same time, the Himalayas remain a spiritual haven. For thousands of years, sages, travelers, seekers, and explorers have journeyed into these valleys to meditate, learn, and discover themselves. Every stone, every meadow, and every silent corner feels infused with timeless wisdom.

In this article, we will explore the major mountain ranges of the Himalayas — the Western, Central, and Eastern Himalayas — along with their geology, climate, biodiversity, and cultural importance. You will also find real experiences, inspiring observations, and insights into the environmental challenges that the region faces today. This is not just a geographical overview; it is an immersive journey into the heart of the world’s most majestic mountain system.

So let us begin this exploration — a journey through landscapes carved by time, stories shaped by nature, and mountains that continue to inspire millions across the world.

Himalayan Overview — Geology, Formation and Importance

The Himalayas are among the youngest yet most powerful mountain systems on our planet. Stretching across nearly 2,400 kilometers, this massive range influences the geography, climate, cultures, and ecosystems of five nations — India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, and Pakistan. To describe the Himalayas as “just mountains” would be an understatement; they represent an intricate natural system that governs life, water, weather, and human civilization in countless visible and invisible ways.

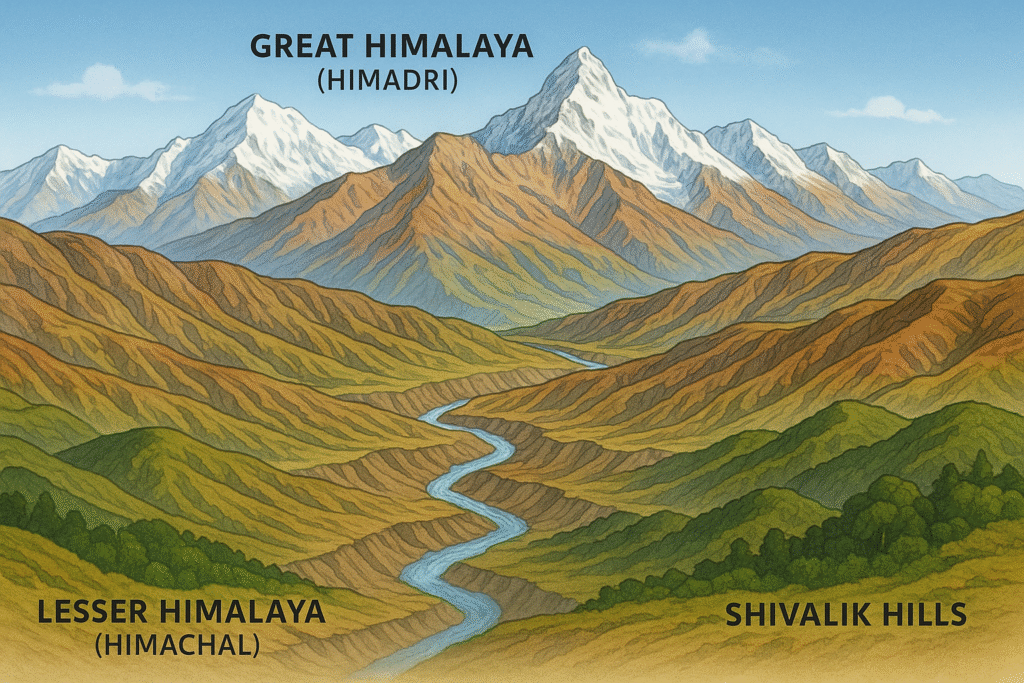

Geographically, the Himalayas are divided into three major sections: the Great Himalaya (Himadri), the Lesser Himalaya (Himachal), and the Shivalik Ranges. Each zone has its own climate, biodiversity, soil composition, altitude variations, and cultural heritage. This layered structure makes the Himalayas one of the most diverse mountain systems in the world. The Great Himalaya is home to several of the planet’s highest peaks, including Mount Everest, Kangchenjunga, Annapurna, Nanda Devi, and Makalu — mountains that attract climbers, researchers, and spiritual seekers from across the globe.

Geological Formation — A Collision That Shaped a Continent

The Himalayas were formed around 50 million years ago when the Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate. This collision was so powerful that the sediment from the ancient Tethys Sea rose upward, eventually giving birth to the majestic mountains we see today. Geologists believe the Himalayas are still rising by a few millimeters every year, making them a living geological structure that continues to evolve.

The formation of the Himalayas did not just create a physical barrier; it reshaped Asia’s entire climate system. The mountain range plays a crucial role in directing monsoon winds, controlling rainfall patterns, and preventing cold Central Asian winds from sweeping across the Indian subcontinent. Without the Himalayas, the fertile plains of India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh would be dry, barren landscapes. The mountains, therefore, act not only as a natural fortress but as a climate regulator for millions of square kilometers.

Importance of the Himalayas — Water, Life and Ecological Balance

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

The Himalayas are often called the “Water Tower of Asia” as they give birth to some of the continent’s most important rivers — the Ganga, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, Indus, Sutlej, and Teesta. These rivers sustain the lives of hundreds of millions of people, providing drinking water, irrigation, hydroelectric power, and fertile soil that supports agriculture across vast regions.

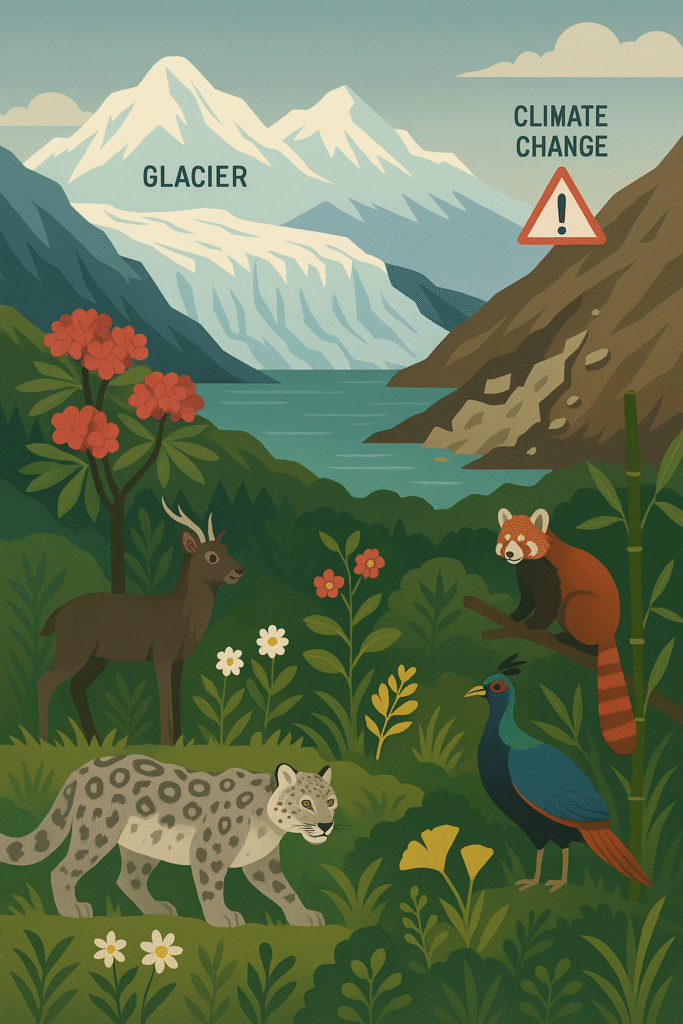

Ecologically, the Himalayas are one of the richest biodiversity hotspots in the world. The lower slopes are covered with dense forests of pine, oak, rhododendron, and cedar, while the higher altitudes host unique species adapted to extreme cold. The snow leopard, red panda, Himalayan black bear, musk deer, and countless birds and butterflies make this region a paradise for biologists and conservationists. Every valley and forest in the Himalayas has its own ecological identity — shaped by altitude, climate, and traditional knowledge of local communities.

The Himalayas and Human Civilization — A Spiritual and Cultural Bond

Beyond their physical grandeur, the Himalayas hold immense spiritual significance. For thousands of years, sages, yogis, travelers, poets, and explorers have visited these mountains in search of peace, wisdom, and enlightenment. Sacred rivers, holy shrines, ancient monasteries, and pilgrimage routes have woven the Himalayas deeply into the cultural and religious foundations of South Asia.

The cultural traditions of Himalayan communities — from the Ladakhi highlands to the villages of Sikkim — reflect harmony with nature. Their festivals, folklore, music, and lifestyle are shaped by the landscape that surrounds them. For these communities, the Himalayas are not merely mountains; they are protectors, guides, and symbols of resilience.

This brief overview makes it clear that the Himalayas are more than towering peaks. They are the backbone of ecological balance, the source of life-giving water, and a reservoir of ancient wisdom. In the upcoming sections, we will explore the major Himalayan mountain ranges in detail — understanding their unique landscapes, geological features, and the stories they hold.

Major Mountain Ranges of the Himalayas

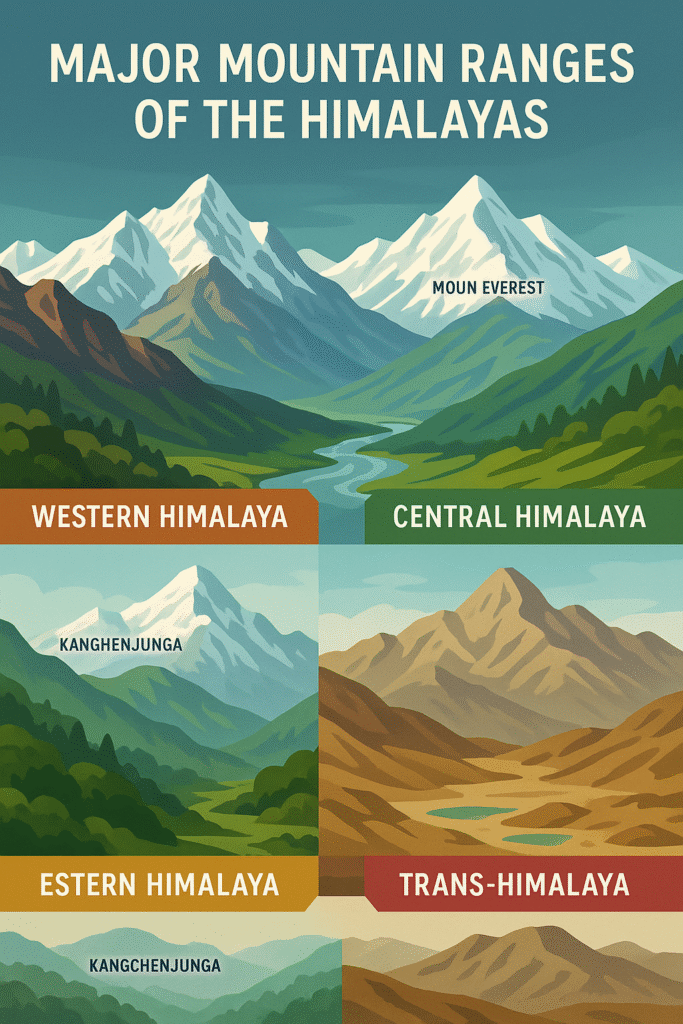

The Himalayas, though often seen as a single continuous wall of mountains, are in fact a mosaic of distinct regions—each shaped by unique geography, climate, ecology, and human history. From the towering ice peaks of the Western Himalaya to the mystical rainforests of the East, and the arid cold deserts of the Trans-Himalaya, each zone reveals a different face of this majestic mountain system. Together, these ranges form a natural fortress, a cultural cradle, and an ecological powerhouse of South Asia.

Western Himalaya

The Western Himalaya stretches across Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, and the western regions of Uttarakhand. It is a land of dramatic contrasts—deep valleys, steep cliffs, lush cedar forests, high-altitude meadows, and vast snow-covered glaciers. The region is known for its rugged terrain, spiritual heritage, and extraordinary biodiversity, making it one of the most culturally and ecologically rich parts of the Himalayan arc.

Geography and Major Peaks

This region hosts some of the most iconic Himalayan peaks, including Nanda Devi, Trishul, Kamet, Panchachuli, and the mighty Nanga Parbat near the Karakoram. Nanda Devi—India’s second-highest peak—stands as the center of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, surrounded by deep gorges, high glaciers, and pristine alpine zones. The geography is bold and diverse: river-cut valleys, glacial basins, and some of the oldest exposed rocks in the Himalayas.

Flora, Fauna and Ecology

Western Himalayan forests include deodar cedar, Himalayan fir, pine, birch, and vast alpine meadows. Rare species like the snow leopard, Himalayan black bear, musk deer, bharal (blue sheep), monal pheasant, and Himalayan fox thrive in its diverse ecosystems. Elevation changes bring sharp climatic variations—from warm temperate valleys to cold, windswept summits. It is one of the world’s richest regions for medicinal plants.

Culture, Communities and Traditions

The region is home to culturally vibrant communities—Kashmiri, Ladakhi, Gaddi, Kinnauri, and Garhwali. Their traditions are steeped in folklore, music, spiritual rituals, and nature-based festivals. Agriculture, pastoralism, apple farming, wool production, and traditional crafts form the backbone of the economy. Monasteries in Ladakh and temples in Himachal and Uttarakhand reflect a unique blend of Buddhism and Hinduism.

Trekking, Adventure and Spiritual Tourism

Western Himalaya is a global hotspot for trekkers. Valley of Flowers, Roopkund, Spiti, Kullu, Pangi, Har ki Doon, Kedarnath, Badrinath, and Ladakh attract thousands of adventure seekers every year. High peaks like Nanda Devi and Nanga Parbat have been renowned centers of mountaineering for decades. The entire region feels like a living museum of culture and natural beauty.

Central Himalaya

The Central Himalaya covers large parts of Uttarakhand (Kumaon and Garhwal) and Nepal. This region is often considered the heart of the Himalayan system due to its massive glaciers, sacred landscapes, and dramatic altitudinal variations. Here, mountains rise sharply into the sky, rivers carve deep gorges, and ancient cultural centers thrive peacefully alongside modern trekking routes.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Major Peaks and Terrain

The region hosts the greatest concentration of high peaks on Earth, including Mount Everest (Sagarmatha/Chomolungma), Lhotse, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Manaslu, Annapurna, and Dhaulagiri. These peaks form the backbone of global mountaineering and exploration. The topography varies from rich river valleys to extreme vertical cliffs, high passes, and glacial amphitheaters.

Glaciers and River Systems

Some of Asia’s most important rivers originate here: Ganga (from Gangotri Glacier), Yamuna (from Yamunotri), Kali, Saraswati, Bagmati, and the Nepalese Trishuli. Dozens of active glaciers, glacial lakes, and snow-fed streams create a massive freshwater system. The region is also vulnerable to GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods), making it an important center for climate research.

Biodiversity and Forests

Central Himalaya has lush temperate forests of oak, rhododendron, pine, fir, and birch. Rare species such as the red panda, Himalayan tahr, musk deer, and monal thrive here. Higher elevations host alpine meadows rich in medicinal herbs. The diverse climate zones support thousands of plant species, many of which are endemic.

Cultural Depth and Spiritual Significance

Nepal and Uttarakhand are spiritual powerhouses. Ancient temples in Garhwal, the cultural richness of Kathmandu Valley, Buddhist monasteries in Nepal, and yoga-meditation traditions make the region deeply spiritual. Pilgrimage routes like Kedarnath, Badrinath, and Muktinath are central to the beliefs of millions. The Annapurna Circuit and Everest Base Camp treks attract adventurers from around the world.

Eastern Himalaya

The Eastern Himalaya is the greenest, wettest, and most biodiverse section of the range. It stretches across Sikkim, Bhutan, and Arunachal Pradesh. Unlike the drier western parts, this region receives heavy rainfall, resulting in dense forests, vibrant ecosystems, and mystical cloud-covered landscapes. The region is known for its spiritual energy, ethnic diversity, and ecological treasures.

Geography and Major Peaks

Eastern Himalaya features towering peaks like Kangchenjunga (the world’s third-highest), Pauhunri, Chomo Yummo, Namcha Barwa, and Jomolhari. Many peaks remain partially hidden under thick clouds and mist due to high humidity. The valleys are deep, fertile, and filled with cascading rivers and waterfalls.

Biodiversity and Climate

This is one of the world’s major biodiversity hotspots. The region hosts tropical rainforests, bamboo forests, alpine shrublands, and high-altitude snowfields—all within short distances. Species like the red panda, snow leopard, Himalayan black bear, hoolock gibbon, and black-necked crane thrive here. The climate ranges from warm subtropical valleys to icy high passes, making it an ecological marvel.

Cultural Identity and Local Life

Bhutan’s dzongs, Sikkim’s monasteries, and Arunachal’s tribal heritage give the region a distinct spiritual and cultural depth. Indigenous communities live in close harmony with nature, practicing sustainable agriculture, weaving, herbal medicine, and nature-based rituals. Their traditions preserve ecological wisdom passed down through centuries.

Environmental Challenges

Despite its beauty, the Eastern Himalaya faces issues such as landslides, rapid river changes, deforestation, and climate-induced rainfall shifts. Conservation programs by Bhutan, India, and international agencies aim to protect this delicate environment.

Trans-Himalaya / Lesser Himalaya

The Trans-Himalaya—often called the “Tibetan Himalaya”—is one of the most unique and geologically fascinating sections of the Himalayan system. Spread across Ladakh, the Tibetan plateau, Spiti, and parts of Uttarakhand, it forms a cold, dry, high-altitude landscape unlike the rest of the Himalayas. This region receives minimal rainfall, experiences extreme cold, and is known for its barren yet breathtaking beauty.

Landscape and Geographical Features

The region includes the Zanskar Range, the Karakoram Range (bordering the Trans-Himalaya), and parts of the Kailash-Mansarovar region. Sharp rock ridges, massive glaciers, frozen river valleys, and high-altitude deserts define the terrain. Ladakh is famously called the “Cold Desert of India” due to its low precipitation and harsh climate.

Flora and Fauna

Vegetation is minimal—mostly hardy shrubs, alpine grasses, and cold-resistant plants. However, wildlife is incredibly rare and precious: snow leopards, ibex, kiang (Tibetan wild ass), Himalayan wolf, blue sheep, and arctic foxes are common here. High-altitude lakes like Pangong Tso and Tso Moriri add an irresistible charm to the otherwise stark environment.

Human Life and Culture

Indigenous communities such as the Ladakhi, Tibetan, and Spitian people inhabit this region. Their culture is deeply shaped by Buddhist traditions, stone architecture, wool-based clothing, and high-altitude agriculture. Monasteries such as Hemis, Thiksey, and Tabo highlight the region’s spiritual identity.

Scientific and Ecological Significance

The Trans-Himalaya is crucial for climate science, glaciology, high-altitude ecosystems, and archaeological research. Its ancient rock formations offer insights into Earth’s geological evolution. The region acts as a natural laboratory for studying climate change.

Environment, Biodiversity and Local Communities

The Himalayas are not just a chain of mountains—they are a living ecological system shaped by glaciers, rivers, forests, wildlife, and human cultures that have existed here for thousands of years. Every valley, forest, and meadow contributes to a delicate balance that sustains life across South Asia. Yet, this fragile ecosystem is under increasing pressure due to climate change, rapid development, and environmental degradation. Understanding the Himalayas from an ecological lens is essential for recognizing their global importance.

Biodiversity — A Treasure of Life

The Himalayas are one of the richest biodiversity hotspots on Earth. Their slopes are covered with pine forests, deodar cedar, birch, bamboo groves, rhododendron valleys, and thousands of medicinal plants. As altitude increases, the vegetation shifts—from subtropical forests in the foothills to cold alpine meadows and snow-covered shrublands in the higher reaches. Each layer supports unique ecosystems shaped by climate and elevation.

Wildlife diversity is equally remarkable. Snow leopards, red pandas, musk deer, Himalayan tahr, black bears, monal pheasants, and countless species of birds and butterflies inhabit the region. These species are not only vital for ecological balance but also feature prominently in the folklore, festivals, and cultural beliefs of Himalayan communities.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Environmental Challenges — A Fragile Ecosystem at Risk

Climate change poses the most serious threat to the Himalayas. Rising temperatures are causing glaciers to melt at unprecedented rates, altering river flows and increasing the risk of GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods). The changing climate is also disturbing seasonal patterns, affecting agriculture, water availability, and wildlife migration routes.

In addition to climate-related threats, several human-driven challenges exist:

- Deforestation and illegal timber extraction

- Unplanned urbanization and road expansion

- Tourism pressure and plastic pollution

- Dams and hydropower projects disrupting river ecosystems

- Soil erosion, landslides, and habitat loss

Local Communities — Guardians of the Mountains

Himalayan communities have lived in harmony with nature for centuries. Ladakhi, Garhwali, Kumaoni, Bhutia, Lepcha, Sherpa, Monpa, and various tribal groups practice traditional agriculture, pastoralism, herbal medicine, and sustainable forest management. Their cultural practices emphasize respect for land, water, and wildlife. Many communities still follow seasonal migration routes, sacred forest traditions, and eco-friendly lifestyles that modern conservationists admire.

Cultural traditions also play a major role in conservation. Examples include:

- Sacred groves where trees cannot be cut

- Seasonal grazing practices to protect grasslands

- Traditional water-harvesting and terraced farming systems

- Hindu and Buddhist beliefs centered around rivers, mountains and forests

Conservation Efforts — The Road Ahead

Protecting the Himalayas requires collaboration between governments, scientists, NGOs, and local communities. Key strategies include forest restoration, glacier monitoring, promoting traditional farming, reducing plastic waste, encouraging low-impact tourism, and reviving natural water systems. If humanity maintains harmony with nature, the Himalayas can remain a thriving ecological treasure for future generations.

The Spiritual and Inspirational Meaning of Mountains and Travel Motivation

The Himalayas are far more than a geographical formation—they are a spiritual presence, a silent teacher, and a timeless symbol of inner strength. Standing before the towering peaks, one feels an unusual sense of clarity, humility, and peace. The noise of everyday life fades, replaced by the quiet rhythm of wind, flowing rivers, and distant prayer flags fluttering in the cold air. For many travelers, the Himalayas become a place where the mind slows down and the heart finally begins to listen.

For thousands of years, sages, monks, yogis, and seekers have walked into the Himalayan valleys to meditate, introspect, and search for meaning. The vastness of the mountains creates a sense of perspective—problems that once felt overwhelming begin to shrink, and a new sense of purpose emerges. Many spiritual travelers share a similar experience: that the mountains do not just offer beauty, they offer wisdom. Their silence speaks, and their presence transforms.

Inspirational Lessons — What the Mountains Teach Us

Mountains symbolize patience, resilience, and stillness. Their sheer height reminds us that meaningful goals take time and steady effort. Their silence teaches that answers do not always come from noise—they often come from contemplation. The journey through mountain trails, with its challenges of altitude, weather, and uncertainty, mirrors life itself. Every step forward requires intention, awareness, and courage.

Many travelers describe the Himalayas as a place of “inner awakening.” As you walk through quiet forests, icy ridges, and serene valleys, you begin to shed doubts and reconnect with your true self. The mountains test your limits, but they also reveal your hidden strengths. They remind you that clarity often comes not from rushing—but from slowing down.

Travel Motivation — Practical and Meaningful Tips

A journey into the Himalayas is not just a trip—it is an inner pilgrimage. To make it safer, deeper, and more fulfilling, consider the following:

- Choose low-impact travel: Carry reusable bottles, avoid plastic, and respect local ecosystems.

- Learn from local communities: Observe their harmonious relationship with nature. They are the true guardians of the mountains.

- Adapt slowly: Understand altitude, weather, and terrain. Give your body time to adjust.

- Mentally prepare: Trekking is not only physical—it requires patience, flexibility, and calmness.

- Create space for silence: Spend time in monasteries, riverbanks, and quiet meadows—these places carry the essence of the Himalayas.

If your goal is only to take photos or “reach the top,” you will experience only half the Himalayas. But if you travel with humility, openness, and curiosity, the mountains will offer you something deeper— a renewed perspective on life, a sense of inner strength, and a connection with something greater than yourself.

Ultimately, the Himalayas remind us that travel is not only outward—it is inward. The journey through mountains reconnects you to nature, to silence, and to your own inner voice. So when you walk into the Himalayas, let your footsteps be slow, your heart open, and your mind free.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Conclusion

The Himalayas are not just a geographical formation—they are a timeless symbol of resilience, harmony, and spiritual depth. Their peaks inspire courage, their valleys nurture life, and their rivers sustain millions across the subcontinent. From the rugged heights of the Western Himalaya to the sacred landscapes of the Central region, the mystical greenery of the East, and the silent deserts of the Trans-Himalaya, each part of this vast mountain system carries its own story, its own wisdom, and its own unmatched beauty.

The purpose of this article is not only to provide knowledge but also to inspire you to see the Himalayas as a living heritage—one that needs respect, awareness, and collective responsibility. As climate change, modernization, and ecological imbalance continue to affect this fragile ecosystem, it becomes crucial for all of us to play a role in preserving it. The Himalayas have given humanity so much; now it is our turn to protect them for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the highest peak in the Himalayas?

The highest peak in the Himalayas is Mount Everest, standing at approximately 8,848.86 meters. Located on the border between Nepal and Tibet, it is the tallest mountain on Earth and a major destination for climbers worldwide.

2. Why are the Himalayas called the “Water Tower of Asia”?

The Himalayas are the source of major rivers such as the Ganga, Yamuna, Brahmaputra, Indus, and Teesta. These rivers provide fresh water to hundreds of millions of people across Asia, which is why the Himalayas are often referred to as the “Water Tower of Asia.”

3. What should travelers keep in mind while visiting the Himalayas?

Travelers should adapt to altitude gradually, check weather conditions, pack light, minimize plastic use, follow local guidelines, and respect cultural norms. Hiring local guides also ensures a safer and more meaningful travel experience.

4. Which rare wildlife species are found in the Himalayan region?

The Himalayas are home to rare species such as the snow leopard, red panda, Himalayan black bear, musk deer, Himalayan tahr, and a variety of high-altitude birds. These animals contribute to the unique biodiversity of the region.

5. How is climate change affecting the Himalayas?

Rising temperatures are causing glaciers to melt rapidly, altering river flows and increasing the risk of GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods). Climate change is also impacting vegetation, wildlife habitats, and traditional mountain livelihoods.

6. Do local communities contribute to Himalayan conservation?

Yes. Indigenous communities practice sustainable agriculture, protect sacred forests, use traditional water systems, and follow eco-friendly lifestyles. Their knowledge and cultural practices make them key contributors to Himalayan conservation.

References

The information presented in this article is based on credible geological, environmental, and cultural research related to the Himalayas. Key data and insights are drawn from the Geological Survey of India (GSI), the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and several peer-reviewed research papers and academic publications. In addition, perspectives from local Himalayan communities, conservation experts, and experienced travelers have been referenced to ensure a holistic understanding of the region.

For further reading, you may explore:

- ICIMOD Himalayan Assessment Reports

- Geological Survey of India Publications

- WWF Mountain Ecosystem Conservation Studies

- UNEP Climate & Mountain Research Documents

- Research articles from Nature, Science & Springer Journals