The Rigvedic society is not just a chapter from ancient history; it is a living reflection of the values, simplicity, and spiritual harmony that shaped early human civilization. This introduction offers a glimpse into the life of the Rigvedic people—how they lived close to nature, how their rituals strengthened social bonds, and how their wisdom continues to inspire modern life. Through this article, you will discover not only the gods, hymns, and sacred rituals of the era but also the everyday actions, family structures, and cultural practices that hold meaningful lessons even today. As you read, you will see how their nature-centered lifestyle, discipline, and collective consciousness can bring peace, clarity, and purpose to our fast-moving world.

Introduction and Historical Background

The Vedic Age occupies a foundational place in the history of South Asia — a period when ritual, poetry, and communal life combined to shape lasting social patterns and spiritual ideas. Often referred to as the earliest phase of the broader Vedic tradition, the Rigvedic period is particularly important because it preserves a large body of hymns and references that give us a window into the everyday concerns, values, and worldviews of early Indo-Aryan speaking communities. Far from being a static or monolithic culture, the society reflected in these texts was dynamic, adaptive, and rooted in close relationships with its natural surroundings. In this section we outline the broad historical contours and then focus on the two key anchors — the textual sources (primarily the Rigveda) and the geography that sustained this civilization.

Scholars reconstruct the Vedic Age by combining linguistic evidence, comparative textual study, archaeology, and ecological inference. The picture that emerges is of small, often semi-nomadic and village-centered communities that gradually settled into more permanent riverine and plain environments. Social life revolved around rituals, cattle and pastoral wealth, reciprocal obligations among kin and clan, and a priestly culture that transmitted sacred knowledge through memorized chants and oral disciplines. The result is an intricate blend of religion, economy, and social practice — one that continues to inform later Indian thought and institutions.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Timeframe of the Vedic Age and Sources (Role of the Rigveda)

Dating the Vedic Age precisely is difficult and has been the subject of substantial scholarly debate. A commonly used broad window places the early Vedic or Rigvedic phase roughly between the late second millennium BCE and the early first millennium BCE. Rather than single-point dates, researchers rely on internal linguistic layers, comparative philology, and cultural markers to order the development of the texts. The Rigveda itself — a collection of hymns addressed to deities and natural forces — is the oldest and most crucial textual witness for this earliest phase.

The Rigveda contains ten books (mandalas) and over a thousand hymns composed in archaic Sanskrit. Its verses praise gods such as Indra, Agni, and Soma, but they also record social practices, references to cattle, pastures, seasonal cycles, and conflict. Because the Rigvedic corpus was preserved through rigorous oral tradition, its language retains extremely archaic features that are valuable for reconstructing both religious practice and aspects of material culture. In short, the Rigveda acts as both sacred scripture and an ethnographic source that allows historians to infer patterns of economy, ideology, and social organization in early Vedic communities.

Geographical Context — Rivers, Environment, and Everyday Life

Geography shaped Vedic life in decisive ways. Early communities were centered in the northwestern parts of the South Asian subcontinent, inhabiting river valleys, plains, and fertile stretches where water and pastures supported mixed pastoral and agrarian economies. Rivers and seasonal watercourses were lifelines: they supplied drinking water, enabled grazing, supported some forms of cultivation, and provided natural corridors for movement and exchange. In the hymns the landscape — rivers, mountains, pastures and forests — is often invoked with sacred language, reflecting how closely religious imagination and environmental reality were entwined.

The environment of the period was more varied than later arid descriptions suggest: grasslands, floodplains, and wooded tracts offered grazing for cattle and wild resources for communities. Such ecological diversity supported a mixed economy where cattle wealth functioned as a key social measure, while emerging cultivation supplemented subsistence and allowed for settled hamlets. Daily life therefore balanced mobility with increasing sedentarization — seasonal movements for pasturing alongside the slow rise of permanent settlements. This interaction between people and place underlies many social customs, ritual calendars, and the profound environmental sensitivity found throughout the Rigvedic hymns.

Economy and Daily Life

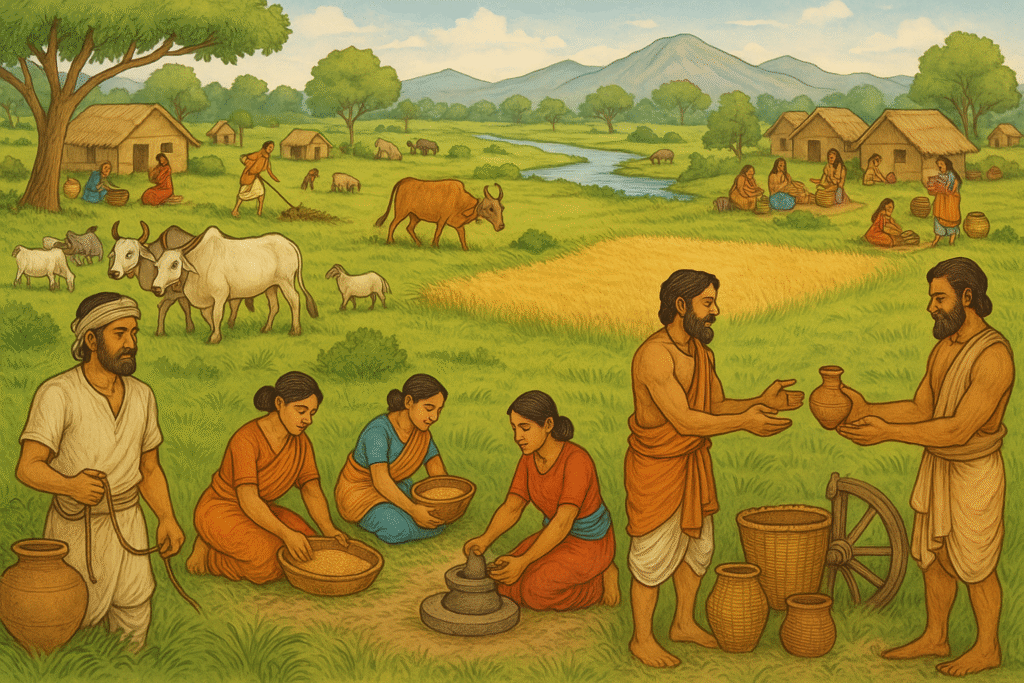

The economic foundations and daily routines of Rigvedic society were deeply intertwined. Communities depended on local natural resources — pastures, rivers, woodlands, and arable strips — and structured their social, religious and familial life around these resources. Wealth was measured less by coin and more by livestock and productive land. Cattle in particular functioned as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and an important symbol of social status. At the same time, developing practices of cultivation, craft and exchange slowly created more settled patterns of life that balanced mobility with growing permanence.

Pastoralism, Agriculture, and Trade

Pastoralism occupied a central place in the early Vedic economy. Herds of cows, sheep, goats and horses provided milk, ghee, hides and draft animals; these products were essential for household consumption, ritual offerings and social gifting. The prominence of cattle in the hymns and the frequent references to pastoral wealth underline how livelihood, ceremony, and prestige were connected. Over time, agricultural activity became more pronounced. Cereals such as barley and millets were cultivated, and the introduction of basic ploughing and sowing techniques allowed communities to settle in favourable floodplains.

Trade in the Rigvedic horizon was mostly local and operated through barter. Surplus grain, livestock, pottery and handcrafted goods were exchanged between neighbouring settlements and seasonal markets. River channels and overland routes enabled movement of people and goods, while reciprocal gift-giving during rituals reinforced social bonds and redistributed resources. Though long-distance merchant networks of later ages had not yet formed, there is evidence of specialist crafts — metalworking, textile-making, and pottery — which supported early exchange networks and added diversity to the local economy.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Village Life versus Urban Centers (where applicable)

The majority of people lived in village-based settings organized around kinship, clan ties and shared access to pasture and water. Villages operated as cooperative units: decisions were typically resolved through assemblies of elders or leading families, and communal obligations — such as contributions to ritual offerings — helped maintain cohesion. Daily life in these rural communities emphasized mutual dependence, shared labour, and the transmission of customary knowledge from elders to younger generations.

Small town-like clusters or proto-urban centres also existed, though they were not comparable to the fully urbanized cities of later civilizations. These centres often functioned as nodes for specialized craft production, ritual activity and limited trade. Where multiple lineages and specialists gathered—priests, artisans, and occasional merchants—the pace of exchange increased and social interactions broadened. Still, the overall pattern remained predominantly rural, with urban features present in embryonic form.

Everyday Tasks, Useful Objects, and Technology

Everyday work in Rigvedic communities combined routine tasks with ritual duties. Men commonly tended herds, maintained pastures, guarded community holdings and managed seasonal agricultural tasks. Women played central roles in household management, food processing (including churning butter and preparing grains), weaving, and the preparation of ritual offerings. Children learned practical skills through participation in family tasks — a living apprenticeship that reinforced social values and occupational continuity.

Material culture was modest but highly functional. Pottery, woven textiles, carved wooden implements, simple ploughs and sickles, and stone or bronze tools were all part of daily life. Fire technology — from cooking hearths to specialised ritual fires — held both domestic and sacred importance. Craftsmanship shows attention to local materials: leatherwork, bone tools, basketry, and early metallurgy were adapted to community needs. These technologies, though not industrialized, were resilient and well-suited to the ecological contexts in which people lived.

The economic and day-to-day arrangements of the Rigvedic world teach a number of enduring lessons: resource awareness, the value of distributed (non-monetary) wealth, the importance of social reciprocity, and the virtue of skills transmitted across generations. Even in contemporary contexts, the balance between mobility and settlement, community-based resource management, and practical, low-impact technologies remain relevant for sustainable livelihoods.

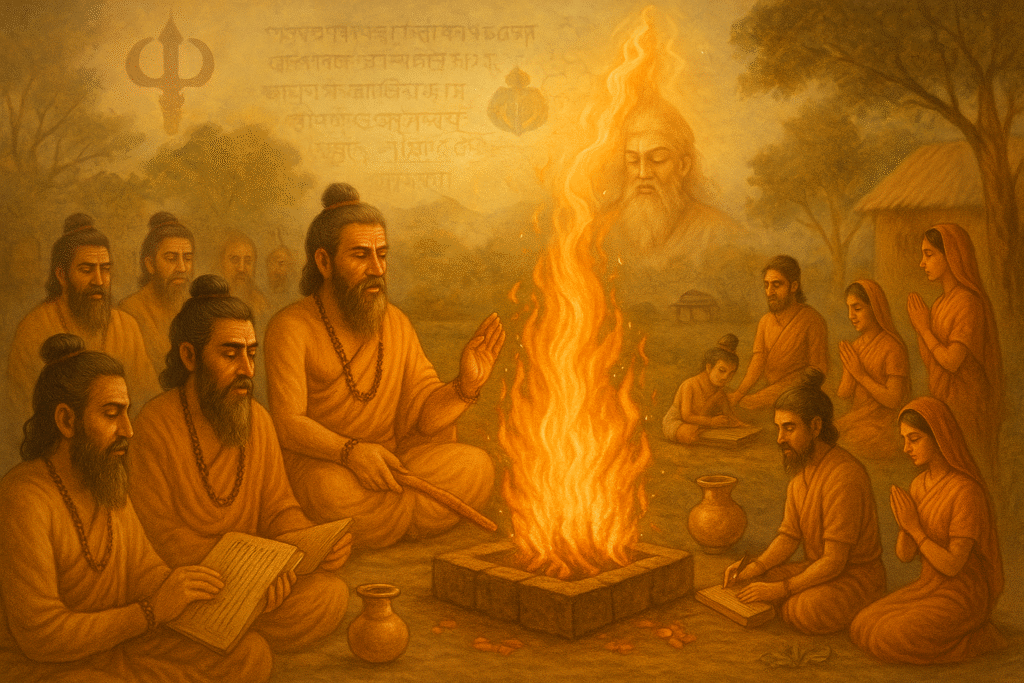

Religious Practices and the Yajña Culture

Religious life in the Rigvedic world was not confined to private devotion; it shaped communal identity, economic redistribution, and moral order. Rituals, hymns, and public sacrifices (yajñas) structured time and social interaction, providing regular occasions for collective participation, gift-giving, and reaffirmation of shared values. The sacred and the social were braided together: liturgy organized social obligations, while community structures gave ritual its force. In what follows we explore the primary gods, the social meaning of yajña, and the institutional forms—mantras, āśramas, and priests—that sustained this ritual culture.

Major Deities: Indra, Agni, Soma and Others

The Rigvedic pantheon is rich and somewhat different from later classical Hinduism. Several deities dominate the hymns because they embody forces that mattered most to early communities. Indra appears as the warrior and storm-god — a symbol of martial courage, the breaker of obstacles and the bringer of rains. Many hymns celebrate his feats, especially the slaying of Vṛtra, a mythic act that releases waters and fertility for humankind.

Agni, the fire, holds a central mediating role. As the household hearth and the sacrificial fire, Agni is the communicator between humans and gods: offerings poured into the fire are believed to reach the gods through Agni’s agency. Agni’s presence ties domestic life to public sacrifice, and his invocation is essential in almost every ritual context.

Soma is complex — a sacred plant or its pressed juice, a ritual drink, and a divinized power. Soma’s consumption in ritual intoxication is associated with ecstatic insight, poetic inspiration, and poetic praise. The hymns addressed to Soma describe its energizing and purifying effects, binding the community through shared ritual experience.

Alongside these principal figures are a constellation of other powers — Varuṇa (cosmic order and moral oversight), Pūṣan (guide and protector), the Maruts (storm-entities), and various nature-forces invoked as deities. Together these gods reflect a worldview in which social life, environment, and cosmic order are inseparable.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

The Social and Religious Meaning of Yajña

Yajña (sacrifice) was the focal practice that bound the community. It combined liturgical precision with communal consumption: offerings were presented to gods, priests performed exacting rites, and the ritual culminated in shared feasting and redistribution. This cycle transformed ritual giving into social capital — kings and notable households used yajña to display generosity, consolidate alliances, and reaffirm political legitimacy.

Yajñas operated at multiple scales. Household rites regulated life-cycle transitions — birth, marriage, death — while larger public sacrifices could mobilize wider networks and redistribute wealth. A well-conducted yajña created reciprocal obligations: patrons gave gifts to priests and guests, recipients reciprocated in time or service, and networks of obligation helped stabilize social order. Thus the ritual had political, economic, and moral dimensions, not merely a theological one.

Importantly, yajña also functioned as an ethical technology: it taught discipline (through ritual order), encouraged generosity (through gift-giving), and reminded participants of interdependence (through communal consumption). The ceremonial calendar, tied to seasons and pastoral cycles, knitted spiritual concerns to ecological realities.

Mantras, Āśramas, and the Place of Priests

Mantras — metrically arranged, orally transmitted hymns — were the engine of ritual power. Their correct pronunciation, rhythm, and intonation mattered; precision was believed to affect the efficacy of the ritual. The oral schooling that produced such performers demanded long apprenticeships and strict memory training, ensuring stability across generations.

Educational and social forms such as āśramas or gurukulas functioned as centers where young members of the community learned ritual, ethics, and practical skills. Teachers (ṛṣis or gurus) combined spiritual instruction with social mentorship. These institutions reinforced a shared cultural repertoire and transmitted specialized knowledge that otherwise might be lost in an oral society.

Priests (hotṛs, adhvaryus, udgātṛs — different ritual specialists) held authoritative positions because they guaranteed the correct performance of rites. Their role was technical (performing rites), social (mediating disputes, advising patrons), and educational (teaching mantras and techniques). While priests did not always wield direct political authority, their ritual expertise lent moral weight to decisions and cemented their role as cultural custodians.

In sum, Rigvedic religious life was an embodied system: gods, sacrifices, chants, teachers, and communal ritual all worked together to form a coherent social order. The practices taught discipline, distributed resources, and integrated ecological rhythms into social calendars — lessons that continue to offer insight into how ritual can shape ethical and communal life today.

Politics, Leadership, and Warfare

Political life in the Rigvedic world combined local autonomy, communal decision-making, and the occasional assertion of martial power. Authority was distributed: kings (rājan) and chiefs played prominent roles, but their legitimacy rested on consent, prestige, and the backing of assemblies rather than absolute command. This mixed arrangement allowed communities to respond to threats and opportunities while retaining social cohesion and shared responsibility.

Leadership therefore had multiple faces — the rājan as protector and war-leader, elders and clan heads as custodians of local order, and ritual specialists as moral and diplomatic advisors. Rather than a rigid bureaucracy, power operated through networks of allegiance, gift-exchange, and public reputation. Decisions that affected the group — whether about land use, inter-clan disputes, or ceremonial obligations — were often taken in collective forums where elders, warriors and priests deliberated together.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Village Rule and Collective Decision-making

At the heart of political organization was the village or clan assembly. Known in later sources as sabha and samiti, these gatherings functioned as deliberative bodies: they adjudicated disputes, allocated resources, decided on defensive measures, and organized communal rites. Authority in these contexts flowed from consensus, custom, and the persuasive standing of senior figures, not from coercive fiat.

The rājan often presided over or participated in such assemblies, but his role resembled that of a first-among-equals — a leader whose effectiveness depended on personal valor, generosity (especially through ritual gifts), and alliances. Lineage leaders, respected elders, and ritual experts could all check or advise the ruler. This plural structure promoted accountability: leaders who lost the trust of their community risked losing influence or being replaced by more capable figures.

Collective decision-making fostered transparency and mutual obligation. When resources such as pastures, watercourses, or grazing rights were scarce, communal mechanisms helped manage allocation and reduce conflict. Similarly, public ceremonies and yajñas reinforced social bonds that underpinned political cooperation.

The Warrior-Kṣatriya Role and External Conflicts

Warfare in the Rigvedic period was closely tied to economic stakes — control of pastures, herds, trade routes, and seasonal resources — as well as to honor and prestige. The Kṣatriya or warrior class bore the responsibility for defense and, when necessary, offensive action. Their training emphasized courage, formation, martial skill, and loyalty to the rājan and the clan.

Battles were often localized and seasonal, directed against rival clans, raiders, or competitors for grazing land and livestock. Many hymns celebrate martial exploits, prizes won, and the courage of fighters, indicating that military prowess was a respected source of social authority. At the same time, alliances and diplomacy — forged through marriages, gift-exchange, and shared ritual sponsorship — played a major role in preventing or resolving conflicts.

Priests and ritual specialists sometimes acted as mediators and legitimizers in inter-group disputes, using ceremonial reciprocity and oath-bound exchanges to stabilize relationships. Thus warfare and politics were entwined with ritual practice: victory required both force and the moral sanction that ritual endorsement provided.

In summary, Rigvedic politics combined communal deliberation, charismatic leadership, and a warrior ethic calibrated to protect and expand community interests. This configuration produced a resilient social order where authority was balanced by obligation, and where military action was framed by social norms and ritual legitimacy.

Literary and Intellectual Life

The Rigvedic period was not only an age of ritual and economy but also a vibrant era of poetic composition, intellectual exchange, and disciplined pedagogy. The corpus of hymns, prayers and ritual formulas preserved in the Rigveda captures a lively conversation between composers (ṛṣis), performers, and their communities. This literary culture combined aesthetic invention with mnemonic discipline, producing texts that functioned as both devotional performance and repositories of communal knowledge.

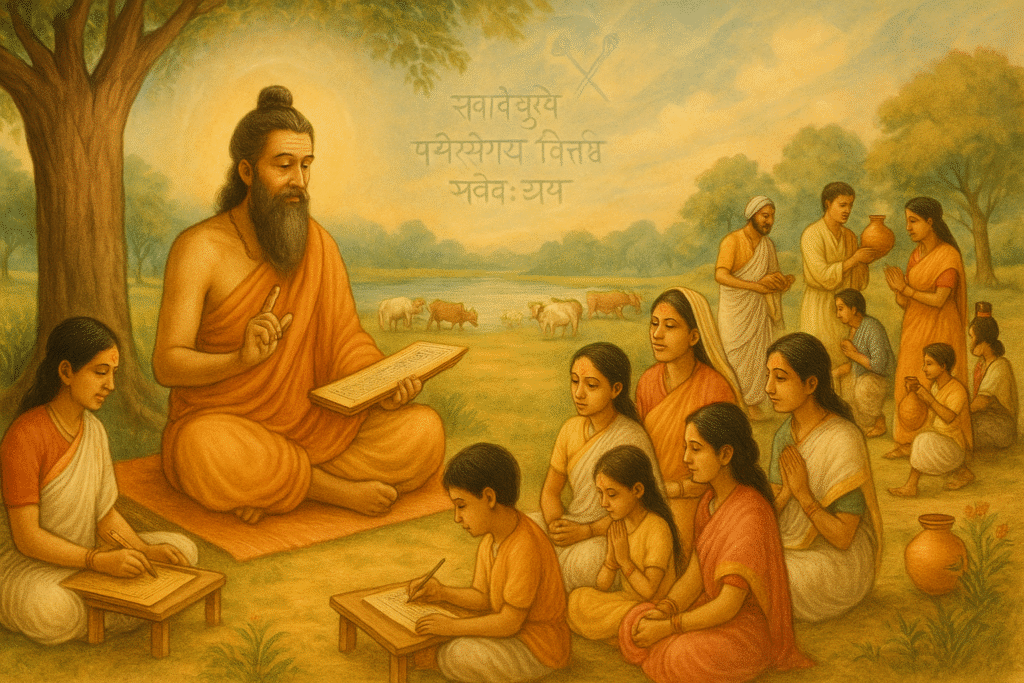

Rishi Tradition, Āśramas, and Modes of Education

Central to Rigvedic intellectual life was the rishi tradition. Rishis were poet-seers—figures who composed hymns, transmitted ritual technique and acted as moral guides. They often gathered disciples and students around them in early forms of āśramas or gurukula-like households. Education was primarily oral, apprenticeship-based and experiential: students learned by listening (śravaṇa), meditating on verses (manana) and reciting them aloud (nididhyāsana). Accuracy of pronunciation, meter and intonation was treated as a moral and technical imperative because ritual efficacy depended on it.

Training in an āśrama combined spiritual instruction with practical skills. Young learners memorized hymns and ritual sequences, practiced ritual enactments, and acquired knowledge about seasons, cattle management, and social duties. Teachers (gurus, rishis) cultivated both intellectual acuity and disciplined habit: memory exercises, repetition, and correction ensured textual fidelity across generations in an otherwise non-literate environment.

Folk Songs, Mantras, and the Preservation of Knowledge

Two complementary channels preserved and circulated knowledge: folk expression and formal mantra tradition. Folk songs—ballads, seasonal laments, work-songs and celebratory chants—carried local memory, social norms and historic recollections. Their simpler idiom and communal performance made them powerful vehicles for shared identity and moral instruction.

Mantras, by contrast, were specialized, metrically strict compositions used in ritual contexts. Their efficacy was believed to hinge on precise enunciation, rhythm and placement. Different ritual specialists (hotṛ, adhvaryu, udgātṛ) mastered distinct chant-corpora, and their technical expertise made them custodians of ritual knowledge. Because writing was rare, this elaborate oral discipline functioned as a robust archive: mnemonic forms, melodic contours and social teaching together preserved a complex body of liturgical and ethical material.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

The interplay of folk creativity and ritualized recitation also supported intellectual plurality. Hymns contain philosophical speculation, cosmological questioning and poetic images that reveal an enquiring mind at work. Debates about fate, the origin of the cosmos and the human role in the world appear not as abstract scholasticism but as living conversations embedded in song and sacrifice.

In short, the literary and intellectual life of the Rigvedic age relied on disciplined oral pedagogy, a rishi-led culture of composition, and the twin streams of vernacular song and formal mantra. This combination ensured both continuity and creativity—preserving tradition while allowing it to be reinterpreted by each generation. The result is a legacy of sound-based knowledge transmission that offers modern readers lessons about education, memory, and the social grounding of learning.

Positive Lessons from Vedic Society

The Rigvedic world offers more than historical curiosity — it carries practical and inspiring lessons for modern life. Rooted in community, reverence for nature, and an ethic of shared responsibility, the Vedic outlook shows how simple practices and collective habits can nurture resilience, purpose and social harmony. Below we highlight three core lessons and then suggest concrete behaviours that readers can adopt today.

Inclusivity, Women's Participation, and a Nature-Centered Ethic

One striking feature of early Vedic society was its relative openness to multiple voices within religious and intellectual life. Women appear as active participants — composing hymns, engaging in ritual, and sometimes receiving initiation for study. This inclusivity suggests that cultural vitality depends on diverse contributions, not narrow gatekeeping. Modern societies that deliberately amplify marginalized voices are likely to be more creative, just and adaptive.

Equally important is the strong nature-oriented ethic visible in Vedic hymns and ritual calendars. Rivers, seasons and pastures were experienced as living partners rather than inert resources. That relationship implied duties as much as rights: care for the land, observance of seasonal rhythms, and restraint when necessary. Translating this ethic into today’s world points toward stewardship rather than exploitation — a small shift with large long-term benefits.

Finally, the Vedic emphasis on community reciprocity — sharing surplus, redistributing through ritual hospitality, and guarding commons — underlines how social safety nets and mutual aid can lessen inequality and strengthen bonds. These practices reinforced social cohesion and reduced friction in times of scarcity.

Behaviours to Adopt in Modern Life

- Prioritise local and seasonal consumption: buy local food, prefer seasonal produce, and support neighbourhood producers.

- Encourage inclusive participation: create spaces at work and in community life where women and minorities can lead and teach.

- Practice ritualized generosity: set aside small, regular acts of giving (time, skills, food) to neighbours or local charities.

- Adopt low-impact routines: reduce waste, repair items instead of discarding, and favour durable goods over disposables.

- Teach oral memory and local stories: share family histories, songs or practical skills with children to preserve cultural knowledge.

- Form small deliberative groups: neighbourhood assemblies or workplace circles can handle local problems collectively and build trust.

In short, the Vedic legacy is not an instruction manual for the present, but a source of guiding principles: inclusion, ecological responsibility and cooperative economies. By borrowing these attitudes — adapted thoughtfully to contemporary realities — we can create communities that are more resilient, humane and sustainable.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Debates and Criticism

The Rigvedic world, like any deep historical subject, invites multiple readings. Early interpretations often celebrate its ritual richness and communal cohesion, while contemporary scholarship emphasizes complexity—contradictions, social tensions, and gradual processes of stratification. To avoid simplistic conclusions, historians combine textual study, comparative anthropology, and archaeological evidence to form a nuanced picture: one in which inclusivity and inequality can coexist in differing measures across time and place.

Was Rigvedic Society Truly Egalitarian? — Historical Debates

Some scholars argue that the early Vedic horizon displayed considerable social fluidity: roles were largely function-based, women took part in ritual and learning, and mobility between occupations seems plausible. Others counter that the seeds of hierarchy already appear—references to varṇa distinctions and elite accumulation surface in ritual texts and social practice. Rather than a binary answer, the evidence suggests a spectrum: elements of openness and shared resources existed alongside emerging patterns of privilege and control. The question, therefore, becomes not whether the society was purely egalitarian, but how varying degrees of inequality developed and were contested within communities.

Change in Later Periods — Summary of Post-Rigvedic Transformations

Moving into the later Vedic and post-Vedic phases, several shifts are apparent: increased agricultural intensification, growth of larger settlements, greater ritual specialization, and the institutionalization of social categories. These processes helped concentrate wealth and authority in new ways—strengthening priestly influence and formalizing social boundaries. Ritual life became more elaborate, and textual genres that codified duty, law and social order grew in importance. Altogether, these transformations mark a transition from a relatively flexible early framework to more structured and hierarchical societies in subsequent centuries.

In short, debates about the Rigvedic world underline the need for careful, context-sensitive readings: early texts reflect living practices that evolved, at times toward inclusivity and at others toward greater stratification. Understanding that trajectory is essential for appreciating the complexity of South Asia’s ancient past.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What time period does the Rigvedic Age generally refer to?

The Rigvedic Age is considered the earliest phase of the Vedic period. Most scholars associate it with the late second millennium BCE, although exact dates vary due to differing interpretations of linguistic and archaeological evidence.

2. Is the Rigveda only a religious text, or does it also serve as a historical source?

While the Rigveda is primarily a collection of hymns and ritual verses, it also contains valuable information about social life, economy, environment, and cultural practices of the time. Therefore, it is both a religious scripture and an important cultural-historical source.

3. Did women participate in education and religious activities during the Rigvedic period?

Yes. Several references indicate that women engaged in learning, composed hymns, and took part in ritual activities. Some women even underwent the upanayana initiation, highlighting their role in intellectual and spiritual life.

4. Was the varna system completely birth-based during this period?

Not in its early form. The varna distinctions mentioned in the Rigveda appear more like functional classifications rather than rigid, hereditary categories. The later strict caste system evolved in subsequent periods, not during the early Rigvedic phase.

5. How are Vedic lessons useful in modern life?

The Vedic values of community cooperation, local resource-based living, environmental respect, and inclusive participation offer practical guidance even today. They encourage sustainable lifestyles and social harmony in a rapidly changing world.

Conclusion

The Vedic period—especially the Rigvedic society—is not merely a chapter of ancient history but a living reservoir of ideas, values, and practices that continue to offer guidance in the modern age. Its emphasis on community-centered decision-making, respect for nature, flexible social structures, women’s participation, and oral traditions of knowledge preservation all highlight a worldview deeply rooted in balance and collective responsibility. These principles reveal how early societies sustained harmony, resilience, and intellectual continuity over long periods.

In a world facing environmental challenges, social fragmentation, and increasing psychological stress, the lessons of the Rigvedic age remain strikingly relevant. Simple actions—such as fostering community bonds, respecting natural resources, empowering women, and valuing traditional knowledge—can contribute meaningfully to personal well-being and social stability. By embracing these insights, we can cultivate lives that are more grounded, mindful, and connected.

References

- Rigveda Saṁhitā — Various Mandalas and Suktas.

- Archaeological and linguistic research studies on Vedic civilization.

- Ancient Indian History — Standard academic and university-level sources (including NCERT).

- Scholarly research papers on Vedic culture, society, and Indo-Aryan studies.

- Supplementary references from Brāhmaṇa texts, Purāṇas, and later Vedic literature.

Social Structure and Family

The social framework of Rigvedic society was organized around kinship, shared responsibilities, and a flexible distribution of roles. The household (gṛha) functioned as the nucleus of economic production, ritual performance, and the transmission of values. Unlike later rigid hierarchies, early Vedic social relations were more fluid, shaped primarily by function, skill, and community expectations. The family was regarded as a sacred unit — a place where moral discipline, practical knowledge, and ritual conduct were learned and preserved. This interconnected network of families formed the backbone of social stability and communal cohesion.

Varṇa System — Early References and Their Meaning

While references to the four varṇas — Brāhmaṇa, Kṣatriya, Vaiśya, and Śūdra — appear in the Rigvedic corpus (notably in the Puruṣa Sūkta), the system in this early period was neither rigid nor entirely birth-based. Instead, it likely represented broad functional distinctions within society. Priestly duties and preservation of sacred knowledge were associated with the Brāhmaṇas; protection, governance and leadership with the Kṣatriyas; agriculture, pastoralism and trade with the Vaiśyas; and various forms of service or craft labour with the Śūdras.

Importantly, this classification was not a strict hierarchy but a means of organizing tasks essential for communal life. Evidence suggests that mobility between roles existed, and expertise or merit could influence one’s position. The rigid, hereditary caste structure of later centuries had not yet crystallized. Thus, the early varṇa framework should be understood as a proto-social division of labor rather than an instrument of inequality.

Status and Education of Women (Upanayana, Female Scholars)

Women in Rigvedic society enjoyed a relatively high degree of respect, autonomy and participation in social as well as religious life. Numerous hymns portray women as articulate, wise, and spiritually capable. Female sages such as Ghoṣā, Apālā, Viśvavārā and Lopāmudrā contributed hymns to the Rigveda and actively engaged in philosophical and ritual dialogue. These attest to their intellectual agency.

Educationally, there is evidence that some women underwent upanayana, the initiation traditionally associated with Vedic study. This implies that women were not excluded from spiritual education or ritual recitation. They participated in yajñas as co-performers, offered prayers, and managed several domestic rituals. In household life, their role extended to food preparation, resource management, early childhood education, and maintaining ritual purity — responsibilities that shaped the family’s religious and social character.

Such involvement demonstrates that women were central not only to the household economy but to cultural continuity and knowledge transmission. Their participation highlights a period in early Indian society where gender roles, while differentiated, were not restrictive in the rigid sense found later.

Marriage, Sacraments, and Social Customs

Marriage (vivāha) was considered a sacred and social institution. It united not only two individuals but two families and lineages. Rituals such as saptapadī (the seven steps), fire circumambulation, and vows of mutual cooperation formed the core of the ceremony. These rites emphasized partnership, reciprocity, and the shared responsibilities of household life. Dowry existed in the form of gifts, but it functioned primarily as a cultural practice of goodwill rather than an economic burden as seen in later periods.

Samskāras (life-cycle rituals) structured an individual’s entire journey — from birth (jātakarma) and naming (nāmakaraṇa) to initiation (upanayana), marriage, and funeral rites (antyeṣṭi). These rituals reinforced the individual’s place within the community, ensured moral upbringing, and aligned personal milestones with cosmic and social order.

Social customs in the Rigvedic age were grounded in collective participation. Festivals, yajñas, communal feasts, and village councils brought people together, enabling dialogue, cooperation and resolution of disputes. Group deliberation, respect for elders, and shared decision-making were considered essential virtues. This participatory ethic strengthened both familial bonds and community governance.

Overall, the social and familial structure of the Rigvedic period reflects a balanced, cooperative, and ethically anchored society. It demonstrates how functional roles, mutual respect, flexible organization and educational opportunities helped create a stable and progressive civilization — laying early foundations for the cultural continuity that would follow in subsequent ages.