History does not merely recount events; it reveals how power, governance, and society transform over time. When I first began studying the Indian Councils Act 1861, it did not appear to me as just another colonial-era legislation. It felt like a turning point—a quiet yet decisive shift that restructured the administrative framework of British India. I still remember the moment when I came across an old archival document that mentioned, “The beginning of structured legislative councils in India.” At that moment, I had no idea that this single line would open the door to an entire chapter of institutional evolution.

After the Revolt of 1857, the British administration realized that governing India through old methods was no longer possible. A vast and culturally diverse territory like India needed a system built not just on authority but on consultation, regional understanding, and shared administrative responsibility. It is in this context that the Indian Councils Act of 1861 emerged—a law that laid the foundation for legislative participation, even though in a limited and controlled form. Today, when we debate laws openly in modern democratic India, it becomes important to understand where these consultative mechanisms originated.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

Although the Act may seem narrow when compared to contemporary constitutional standards, its impact was significant. For the first time, Indians could be nominated to the Governor-General’s Council, setting in motion a new tradition of administrative dialogue. The Act restructured the relationship between the central and provincial governments and introduced a formal legislative process that would eventually evolve into India’s modern parliamentary framework. As I explored the details of the Act, I realized that it marked a critical shift—from unilateral imperial control to an early, cautious form of shared governance.

In this article, I aim to bring together my learning, analysis, and historical insights to explain what the Indian Councils Act 1861 truly represented, why it was enacted, its key provisions, its immediate and long-term consequences, and the lessons it offers for modern governance. To understand the evolution of India’s legislature, constitution, and democratic thought, one must understand the roots of legislative councils—and the journey begins here, with the Act of 1861.

1. Historical Background

To truly understand the significance of the Indian Councils Act 1861, we must travel back to a moment when British India stood at a crossroads—politically shaken, administratively exposed, and socially restless. The Revolt of 1857 had not only disrupted the British regime but had also shattered the illusion that the East India Company’s administrative model could sustain an empire as vast and diverse as India. During my own research, I came across several parliamentary papers written shortly after the revolt, and one statement repeatedly appeared: “India cannot be governed with force alone.” This realization laid the foundation for a new direction in administrative reform.

After the Revolt, the British Crown assumed direct control over India, ending over 250 years of Company rule. This transition was formalized through the Government of India Act 1858. Yet, while this Act shifted authority from a commercial entity to the British Crown, it did little to address the deeper administrative and political challenges that the revolt had exposed. The British now faced two urgent needs—restoring stability in governance and rebuilding trust among India’s educated and influential classes. Without doing so, ruling such a complex and culturally layered society would only invite future instability.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

The British administration realized that centralization alone was insufficient. It needed a system that appeared more inclusive, consultative, and responsive. The idea was not to grant Indians real political power but to create a controlled mechanism of representation that could pacify rising demands for participation. While reading Lord Canning’s correspondence—the Governor-General during that period—I found a striking line: “Inclusion may be limited, but exclusion cannot sustain an empire.” This sentiment captures the emerging political philosophy that shaped the Indian Councils Act 1861.

Before 1861, small legislative experiments had been attempted, most notably through the Charter Act of 1853. But these reforms were narrow in scope, focusing primarily on administrative efficiency rather than legislative participation. They lacked both regional balance and Indian involvement. After 1857, the need for broader reforms became undeniable. The British understood that a structural framework was required—one that would formalize legislation, reorganize provincial authority, and incorporate limited Indian voices into governance, even if merely symbolically.

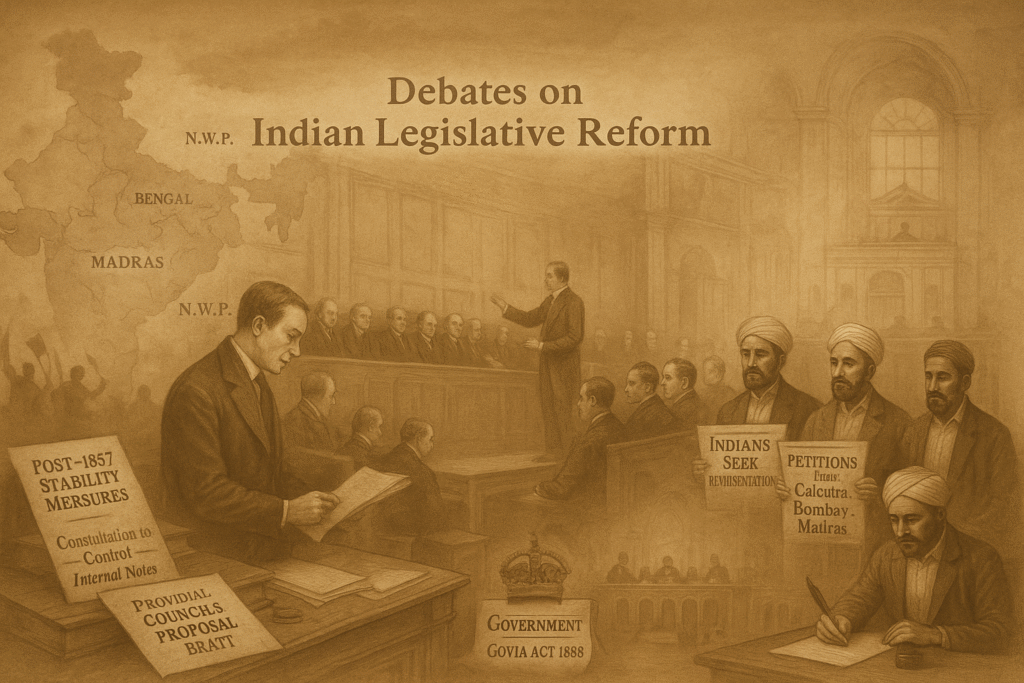

Another significant factor was the emergence of a modern educated class in India. Newspapers, public debates, and growing political consciousness had started demanding transparency, accountability, and some form of legislative presence. Though fragmented and limited, this class carried enough influence for the British to notice. By the early 1860s, petitions from Indian intellectuals in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras began urging the government to open the doors of legislative decision-making. These petitions did not demand full democracy—they simply asked to be heard.

British policymakers were also influenced by debates within the British Parliament. Several members argued that India’s governance needed a legal framework based on consultation rather than unilateral authority. They saw councils not as democratic institutions, but as advisory bodies that could give the appearance of participation while keeping real power firmly in British hands. From the imperial perspective, this approach promised both stability and control.

It was this complex combination of fear, political strategy, administrative necessity, and emerging Indian expectations that created the environment for the Indian Councils Act 1861. The Act was not born out of generosity—it was born out of calculated reform. For the British, it was a mechanism of governance; for Indians, it was the first opening, however narrow, toward legislative involvement.

Thus, the historical background of the Act is not merely a timeline of events. It is the story of an empire forced to rethink its method of rule, a society beginning to find its political voice, and a legislative structure slowly taking shape in the midst of tension, negotiation, and evolving power dynamics. When viewed in this larger context, the Indian Councils Act 1861 becomes more than a legal document— it becomes the starting point of India’s long journey toward representative government.

2. Legislative Causes & Road to the Act

The Indian Councils Act of 1861 did not appear overnight; it was the product of sustained political debate, administrative necessity, and social pressures that accumulated after the Revolt of 1857. In the immediate aftermath, British policymakers confronted hard questions: how to restore stability, how to rebuild legitimacy in the eyes of India’s elite, and how to adapt governance to a vast, diverse territory without relinquishing imperial control. These questions shaped the legislative conversation in London and in Calcutta, setting the scene for reform that aimed to be reassuring rather than revolutionary.

One persistent theme in parliamentary debates was the idea that consultation could serve as a tool of stabilization. Ministers and administrators argued that limited, managed inclusion of Indian voices would reduce resentment and offer a controlled outlet for political expression. This approach was tactical — not altruistic — yet it acknowledged a political reality: exclusion had contributed to unrest, and some formal mechanism of advice and participation could strengthen British rule.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

The Government of India Act 1858, which transferred sovereignty from the East India Company to the Crown, created the political opportunity for more structured reforms. The transfer exposed the limitations of purely executive rule and prompted calls for clearer legislative processes. In government offices and select private correspondences, officials discussed creating councils that could advise on laws and regulations, and provide input on provincial matters. These conversations emphasized structure: who would sit on councils, how they would be appointed, and what legal authority they might exercise.

Regional considerations also played a key role. Administrators realized that governance could not be one-size-fits-all: Bengal, Bombay, Madras, and the North-Western Provinces each had distinct social, economic, and legal conditions. A centralized legislature was ill-suited to manage such diversity. Consequently, the emerging legislative design favored both a strengthened central council and the creation of provincial councils, allowing legislation to be more responsive to local conditions while retaining ultimate authority in the hands of the Crown and its appointed officials.

Another causal thread was the rising political consciousness among educated Indians. A growing class of lawyers, journalists, and civic leaders were increasingly vocal in demanding a say in public affairs. Their petitions, editorials, and private representations did not advocate full self-rule, but they pressed for access to the processes by which laws were made. This pressure, combined with British fears of further unrest, made the idea of nominated Indian members in legislative councils politically defensible.

Debates in the British Parliament and in official memos converged on a pragmatic compromise: councils that appeared consultative, incorporated select Indians by nomination, and provided a framework for provincial input. The Indian Councils Act 1861 therefore embodied a dual logic—it was a device for consolidating imperial authority while introducing a regulated form of participation. In short, the Act was a measured response to a multifaceted crisis: it sought administrative clarity, regional adaptability, political pacification, and symbolic inclusion, all without ceding real power.

Understanding this legislative road is vital because it explains the Act’s character—limited in political empowerment yet significant in institutional effect. The 1861 Act laid down patterns of nomination, advisory participation, and provincial legislation that would be iteratively expanded in later decades. Seen in this light, the Act is less an endpoint than the first step on a slow legislative journey toward broader representation.

3. Key Provisions

The Indian Councils Act 1861 — though compact in legal length — introduced a set of institutional changes whose practical and symbolic consequences were substantial. In this section I unpack the Act’s key provisions, explain how they altered the architecture of colonial governance, and analyse their immediate strengths and lasting limitations. When historians speak of the 1861 Act, they refer less to a single revolutionary reform than to a package of legal adjustments that re-shaped councils at the centre and in the provinces, formalised legislative procedure, and created a narrow pathway for Indian participation.

3.1 Composition and Structure of Councils

One of the most visible changes introduced by the 1861 Act concerned the composition of the Governor-General’s Council. The Act allowed for the expansion of the Council by adding members who could take part in legislative discussions. Crucially, this expansion permitted the nomination of non-official members — including Indians — to sit alongside senior British officials. The Council’s remit now formally combined executive advice with deliberative legislative work.

3.1.1 Nomination and Membership

Membership under the 1861 arrangements was essentially nomination-driven. The Governor-General (and provincial governors) retained the power to nominate members; there was no mechanism for popular election. Nomination criteria were informal and pragmatic: English-educated Indians, prominent local officials, jurists and landowners were typical choices. While nomination brought Indian voices into legislative sessions, it did so under the shadow of executive discretion — a structural limit that shaped the character of participation.

3.2 Legislative Powers and Advisory Role

The Act clarified the councils’ legislative and advisory functions. Councils were empowered to deliberate on bills, propose amendments, and take part in formal debates. However, this influence was primarily consultative. The Governor-General retained decisive authority: his assent or veto could override council views. Therefore, the Act formalised legislative procedure without transferring sovereign legislative power away from the Crown’s representatives.

3.2.1 Procedure and Recorded Debate

A practical innovation was the routinisation of legislative procedure: bills could be tabled, discussed in council, and recorded more consistently. The formalisation of debate and the habit of recording remarks created a new legal-administrative culture — one in which policy was shaped through argumentation, documented responses, and (slowly) public scrutiny. This procedural legacy would prove important in later reforms that deepened legislative engagement.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

3.3 Provincial Councils and Decentralisation

Recognising India’s vast regional diversity, the 1861 Act authorised the creation or strengthening of provincial councils. The goal was pragmatic: issues tied to local law, revenue, and social practice required local knowledge that a centralised body could not efficiently supply. Provincial councils provided a forum to consider local ordinances, enabling more context-sensitive legislation while preserving centralized control over critical matters.

3.3.1 Scope and Limits of Provincial Authority

Provincial councils were given authority to deliberate on local legislative matters, but their powers were circumscribed. Financial control, military matters, and high policy decisions typically remained outside provincial jurisdiction. Provincial members too were generally nominated, and governors retained reserves of authority. The net effect: greater administrative responsiveness without a meaningful shift in sovereign power.

3.4 Executive vs Legislative Balance

A central feature — and tension — of the 1861 Act was the balance it struck between executive prerogative and nascent legislative formality. The Act did not blur this distinction but institutionalised it: councils could advise and debate; executives executed and decided. For the British, this design was deliberate. It allowed the appearance of consultative inclusion while ensuring that executive unity and rapid decision-making in crises remained possible.

3.5 Financial and Military Exceptions

The Act explicitly or implicitly preserved executive control over two sensitive domains: finance and the military. Budgets, major revenue measures and defence policy were treated as subjects where executive discretion continued to dominate. This meant that on questions that directly affected state power — taxation, expenditure and troop deployments — the councils’ consultative status translated into limited practical influence.

3.6 Nomination vs Election: The Limits of Representation

Perhaps the most important normative limitation within the Act was its reliance on nomination rather than election. Nomination allowed the colonial state to include selected Indian elites but prevented the development of representative politics. The Act created a controlled route for elite engagement without enabling a broader democratic constituency to influence policy. In short, representation was symbolic and selective rather than popular and accountable.

3.7 Administrative and Judicial Interplay

The Act also subtly affected the relationship between administrative governance and legal institutions. By embedding legislative debates within a formal council structure, legal norms and administrative policies began to interact more visibly. Counsel’s recorded opinions and the consultations on laws nudged the colonial administration toward more legally grounded policymaking — a shift that made governance slightly more predictable and legally defensible.

3.8 Early Practical Effects and Case Examples

In practice, the nominated Indian members who first entered councils often focused on local legal issues, educational policy, and public works. They used council sittings to voice regional grievances and to suggest technical reforms. Their interventions rarely overturned executive proposals, but they introduced questions that would later be pursued more vigorously in emerging public forums — newspapers, associations and, eventually, early political organisations.

3.9 Summary: Institutional Form, Political Limits

To summarise: the Indian Councils Act 1861 established a layered institutional architecture — expanded central and provincial councils, formalised legislative procedure, and a mechanism for nominated Indian participation. Its significance lies not in immediate political empowerment but in institution-building. The Act created precedents — nomination, recorded council debate, provincial councils — that later reforms would extend. Yet its political limits were clear: the Crown’s representatives retained final authority, financial and military matters remained largely untouched by council influence, and the absence of elections kept the structure elite-oriented. Viewed historically, the 1861 Act is best understood as a carefully calibrated step toward consultative governance rather than a rupture that inaugurated representative rule.

4. Administrative Changes and Practical Outcomes

The Indian Councils Act of 1861 produced measurable administrative changes that went beyond formal law-making: it altered how governance operated in practice. Where decisions had previously been quick, centralized, and often opaque, the Act introduced structured discussion, recorded deliberations, and a greater emphasis on formal procedure. This shift did not instantly democratize administration, but it created institutional habits — minutes, proposals, and consultative sessions — that made governance appear more reasoned and less arbitrary.

One immediate effect was on policy formulation at the provincial level. Provincial councils provided forums where local circumstances could be presented and considered, meaning taxation, revenue collection, public works, and local regulations began to reflect regional inputs, however limited. Administrators started to factor in provincial reports and council recommendations, which nudged policy toward greater contextual sensitivity rather than purely centralized directives.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

For the civil service, routines and paperwork grew in importance. Record keeping, drafting formal opinions, and preparing council papers became regular tasks. These procedural changes improved documentation and created an evidentiary trail for decisions — a modest but important step toward administrative accountability. Though judicial and police administration saw limited direct reform from the Act, the bureaucratic move toward documented decision-making would later support demands for transparency and review.

The inclusion of nominated Indian members in councils also had practical consequences. Even if their authority was restricted, their presence brought concrete local issues into legislative conversations — roads, schools, irrigation, and municipal concerns found voice in council chambers. This led to more frequent consideration of grassroots problems during budget allocations and administrative planning, producing incremental improvements in public services and project prioritization.

In sum, the 1861 Act’s administrative legacy was mixed but significant: it strengthened procedural governance and created channels for provincial input, while leaving ultimate authority intact in the hands of the Crown and its appointees. The changes were evolutionary rather than revolutionary — they established administrative norms of consultation, documentation, and localized attention that would gradually enable later reforms toward broader representation and accountability.

5. Political Impact

5.1 Impact on Public Consciousness and Political Awareness

The Indian Councils Act 1861 had a profound symbolic effect: it placed Indians, however selectively, within formal channels of governance. This symbolic inclusion mattered. For the first time, public debates and petitions from educated Indians began to translate into the language of official policy-making. Newspapers, civic associations, and legal forums amplified questions about representation, accountability, and administrative transparency. Even though the Act did not create mass politics, it accelerated political literacy among urban elites—lawyers, journalists, and teachers—who now had a clearer sense of how government decisions were made and where to press for change.

5.2 Emergence of New Leadership

The nomination mechanism under the Act indirectly encouraged a new kind of political leadership. Individuals who were literate in English, versed in law or administration, and socially influential found pathways into council deliberations. These nominated members began to cultivate public profiles, sharpening rhetorical and organizational skills that later proved crucial for political mobilization. While not yet party-based or mass-oriented, this nascent leadership formed the nucleus of subsequent political movements and provided a cadre of experienced interlocutors between Indian society and the colonial state.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

5.3 Limits of Representation and Indian Responses

It is important to stress the limits: representation remained nomination-based, not electoral, and real power stayed with British appointees. Many Indian observers criticized the arrangement as tokenistic; some dismissed it as a carefully managed façade of participation. Nevertheless, the experience of engagement—asking questions in council, debating budget items, or raising local grievances—was instructive. It taught Indian leaders how to frame demands, use petitions effectively, and create public pressure—skills that later underpinned calls for wider franchise and legislative reform.

5.4 Imperial Strategy and Parliamentary Politics

From the British perspective, the Act served a tactical purpose. It offered the Crown a way to mitigate unrest by channeling Indian discontent into controlled advisory structures. Debates in the British Parliament reflected this pragmatic calculus: many MPs supported “managed inclusion” as a tool of imperial governance—enough consultation to placate elites, but not enough to cede authority. In short, the Act institutionalized a mode of governance that combined centralized power with limited consultative practices.

5.5 Long-term Political Consequences

In the long view, the 1861 Act functioned as an institutional seed. It established practices—council debate, recorded proceedings, and provincial deliberation—that subsequent reforms expanded upon. Later acts and movements built on the precedent of consultation and incremental representation, moving gradually from nomination to elective devices and wider participation. Thus, while the immediate political effects of the Act were constrained, its legacy was durable: it normalized legislative processes and created institutional spaces that would eventually become instruments for political change.

6. Reception & Critique

The Indian Councils Act 1861 received a mixed reception from its earliest days. For many British administrators and conservative commentators, the Act represented a pragmatic attempt to stabilize governance after the upheaval of 1857. They praised its formalization of consultative procedures and argued that the creation of councils would make decision-making appear more deliberative and legitimate. From this perspective the Act was seen as a measured corrective—a way to channel dissent into institutional forums without relinquishing control.

Indian responses were more ambivalent and often critical. While the nomination of Indians to council seats was welcomed symbolically, many leaders and intellectuals regarded the arrangement as largely tokenistic. The central critique was straightforward: representation under the Act was nominated, not elective, which meant that real political authority and accountability remained concentrated in the hands of British appointees. Critics argued that this limited inclusion risked creating the illusion of participation while leaving substantive power untouched.

Contemporary Indian-language and English-language newspapers captured this divide. Some papers treated the Act as a modest but useful reform that might improve administrative responsiveness; others accused the government of offering a façade of consultation. Editorials and opinion pieces questioned whether nominal inclusion could satisfy broader demands for recognition and influence, and whether such measures would merely delay, rather than defuse, more forceful demands for reform.

Debates in the British Parliament reflected similar tensions. Supporters claimed the Act struck an appropriate balance between imperial authority and local advice, framing councils as tools for stability. Opponents warned that inadequate reforms could foster resentment and that a failure to expand genuine participation would ultimately be counterproductive. In hindsight, some of these dissenting voices proved prescient as later decades saw sustained agitation for deeper legislative representation.

In summary, the reception of the 1861 Act combined cautious approval with pointed critique. It created a legal framework for consultation and modest inclusion, but its limits—nomination over election, restricted authority on key matters, and continued central control—kept many Indians unconvinced. Nevertheless, the Act’s establishment of formal council procedures was consequential: it institutionalized legislative dialogue and set precedents that later reforms and political movements would build upon. Even critics acknowledged that, while insufficient, the Act initiated an important institutional shift in colonial governance.

| 👉 Buy on Amazon |

| As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. | |

7. Long-term Legacy

The Indian Councils Act of 1861 is best understood not for its immediate political power but for the institutional precedents it established. While limited in scope, the Act laid down patterns of legislative procedure, administrative consultation, and provincial deliberation that shaped India’s later constitutional evolution. Seen from a long-term perspective, the Act functioned as an institutional seedbed—small at first, but consequential over decades.

First, the Act formalized practices of debate, record-keeping, and deliberation within a legislative framework. Council sittings generated papers, minutes, proposals, and recorded discussions—habits that gradually became part of legislative culture. These procedural norms later fed into more complex parliamentary practices; future reforms and representative bodies inherited a language of legislation and an expectation that public decisions should be debated and documented.

Second, by recognizing the need for provincial councils, the Act introduced an early logic of localized law-making. Even though powers remained heavily centralized, the idea that provincial conditions required specific consideration anticipated later moves toward federal and provincial autonomy. Subsequent reforms and Acts expanded on this notion, but the conceptual groundwork—acknowledging regional difference within a single polity—can be traced to 1861.

Third, the presence of nominated Indian members—however restricted—helped cultivate political skills, networks, and public profiles among early leaders. These members learned how to frame arguments, utilize petitions, and navigate administrative procedures. The practical experience of participation, limited as it was, contributed to the emergence of an organized public sphere that would later press for electoral representation, broader franchise, and accountable government.

Fourth, the Act demonstrated a strategic approach to imperial governance: “managed inclusion.” From the British viewpoint, councils served to channel dissent into institutionalized forums, reducing the risk of open rebellion while preserving ultimate control. For India’s political development, this strategy had paradoxical effects—it delayed full self-rule but also normalized consultative institutions that reformers and nationalists could later repurpose.

Finally, the 1861 Act’s legacy is a reminder that constitutional change is often incremental. Landmark transitions rarely emerge fully formed; they grow from modest reforms, contested practices, and accumulated experience. The Act did not create democracy, but it created space—procedural, rhetorical, and institutional—for representative politics to take root.

In sum, the Indian Councils Act 1861 occupies a formative place in India’s parliamentary history. Its long-term significance lies in the routines it established, the provincial logic it endorsed, and the early political training it offered—elements that, taken together, helped shape the trajectory from colonial administration toward representative government.

8. Conclusion & Key Lessons

The Indian Councils Act 1861 teaches us that political and constitutional evolution is rarely abrupt—it unfolds gradually, shaped by small but meaningful reforms. Although the Act was limited in its immediate impact and offered only controlled participation, it marked the beginning of formal legislative engagement in British India. Its true importance lies not in what it achieved instantly, but in the institutional foundations it laid for India’s long journey toward representative governance.

One of the key lessons from the Act is that even symbolic or restricted spaces for discussion can stimulate political awareness and public engagement. The nominated Indian members who entered the councils gained experience in legislative dialogue, questioning policies, presenting local concerns, and understanding procedural governance. These early interactions nurtured political confidence and prepared a generation of leaders who later played central roles in demanding broader representation, electoral reforms, and responsible government.

Another crucial takeaway is that stable governance requires consultation, not just authority. The British administration realized—perhaps reluctantly—that structured dialogue helps sustain legitimacy and reduces the disconnect between rulers and the ruled. In modern contexts, this principle remains relevant: transparency, discussion, and inclusion form the backbone of any effective democratic system.

Ultimately, the legacy of the Indian Councils Act 1861 reminds us that significant political change often begins with modest institutional steps. While the Act did not grant real power or democratic rights, it created the procedural and ideological space in which the demand for these rights could grow. It stands today as a reminder that incremental reforms, however small, can shape the trajectory of a nation’s constitutional future.

8. Conclusion & Key Lessons

The Indian Councils Act 1861 teaches us that political and constitutional evolution is rarely abrupt—it unfolds gradually, shaped by small but meaningful reforms. Although the Act was limited in its immediate impact and offered only controlled participation, it marked the beginning of formal legislative engagement in British India. Its true importance lies not in what it achieved instantly, but in the institutional foundations it laid for India’s long journey toward representative governance.

One of the key lessons from the Act is that even symbolic or restricted spaces for discussion can stimulate political awareness and public engagement. The nominated Indian members who entered the councils gained experience in legislative dialogue, questioning policies, presenting local concerns, and understanding procedural governance. These early interactions nurtured political confidence and prepared a generation of leaders who later played central roles in demanding broader representation, electoral reforms, and responsible government.

Another crucial takeaway is that stable governance requires consultation, not just authority. The British administration realized—perhaps reluctantly—that structured dialogue helps sustain legitimacy and reduces the disconnect between rulers and the ruled. In modern contexts, this principle remains relevant: transparency, discussion, and inclusion form the backbone of any effective democratic system.

Ultimately, the legacy of the Indian Councils Act 1861 reminds us that significant political change often begins with modest institutional steps. While the Act did not grant real power or democratic rights, it created the procedural and ideological space in which the demand for these rights could grow. It stands today as a reminder that incremental reforms, however small, can shape the trajectory of a nation’s constitutional future.