Introduction — The World of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are more than archaeological sites; they are windows into some of the earliest examples of planned urban life, communal sanitation, and vibrant civic culture. When I first encountered photographs and excavation reports of these ruins, it felt as if a long-closed curtain was being drawn back — every brick, seal, and pathway hinted at lives once organized with surprising sophistication. This introduction gives a clear, engaging preview of what the reader can expect: a balanced mix of archaeological detail and human storytelling.

The article blends concise scholarship with personal reflection. We will examine the distinctive features of urban design — grid streets, standardized baked bricks, and advanced drainage — alongside artefacts such as inscribed seals, terracotta figurines, and craft objects that reveal economic and cultural links across regions. Interspersed with these facts are short anecdotes from my own journey into the subject: moments when a single museum display or a photograph of a mud-brick lane transformed a dry list of dates and facts into a living narrative.

For both readers and search engines, the opening includes core terms — Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Indus Valley Civilization — so the article’s aim is immediately apparent. More importantly, the structure follows a narrative rhythm: factual description followed by a human response; archaeological interpretation followed by modern relevance. This makes the material accessible, memorable, and useful for anyone curious about how early urbanism shaped human life.

After this introduction, the article will cover discovery and dating, urban architecture and public utilities, social and economic life, art and script, unanswered questions, and the practical lessons these sites offer for contemporary planners and communities.

1. History and Discovery of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

The story of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro stands among the most fascinating chapters of human civilization. Nearly 5,000 years ago, when the civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia were flourishing, another remarkably organized urban society emerged along the banks of the Indus River. Today, we know it as the Indus Valley Civilization or the Harappan Civilization — one of the earliest and most sophisticated examples of city-based human life.

The first evidence of this civilization was uncovered in 1921, when Dayaram Sahni excavated the site of Harappa in present-day Pakistan’s Punjab region. A year later, in 1922, R. D. Banerji discovered Mohenjo-daro (“the Mound of the Dead”) near the Indus River in Sindh. These two discoveries revolutionized Indian history — until then, scholars believed India’s past began with the Vedic period. The ruins of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, however, revealed an advanced civilization that had flourished long before the Vedas were composed.

1.1 The Discovery Story — From Archaeology to History

When the excavations began, archaeologists were astonished to uncover burnt brick walls, well-laid streets, pottery, bronze figurines, and seals beneath the mounds. The precision in their construction amazed even modern engineers: bricks were standardized, streets ran in perfect right angles, and the drainage system was so advanced that it rivaled some modern cities. Gradually, it became clear that this was not a simple agrarian settlement — it was a full-fledged urban civilization built on order, sanitation, and trade.

1.2 A Personal Glimpse — My First Inspiration

The first time I saw an image of the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, I wasn’t merely looking at an ancient structure — I was witnessing the living imagination of humanity. That image struck me deeply; it told me that civilization is not just about buildings, but about a mindset — an organized, disciplined way of life. For me, studying the Indus sites became more than academic curiosity; it was a journey through time, realizing how cooperation and planning form the backbone of any lasting society.

Archaeological evidence shows that the civilization flourished roughly between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE. Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were its two major centers, but other sites such as Dholavira, Lothal, Kalibangan, and Rakhigarhi were equally significant. The entire civilization covered nearly 1.2 million square kilometers, extending across northwestern India and Pakistan — a scale much larger than that of contemporary Egypt or Mesopotamia.

1.3 Archaeological Evidence and Findings

The excavations revealed seals engraved with animals and symbols, suggesting a writing system that remains undeciphered even today. Artifacts such as the bronze dancing girl and the bearded priest-king statue showcase a refined artistic sensibility. Granaries, wells, and drainage channels indicate a society that prioritized cleanliness, order, and water management — traits that reflect an advanced understanding of civic life.

The discovery of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro teaches us that civilization is not just about grand monuments but about a collective vision that organizes life sustainably. At a time when modern cities struggle with pollution and planning crises, the lessons from these ancient urban centers feel strikingly relevant.

In essence, the discoveries of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro transformed our understanding of the Indian subcontinent’s past. They demonstrated that India’s cultural and technological roots are far older and more sophisticated than once believed. More than historical relics, they are reminders of how human creativity and discipline can endure across millennia.

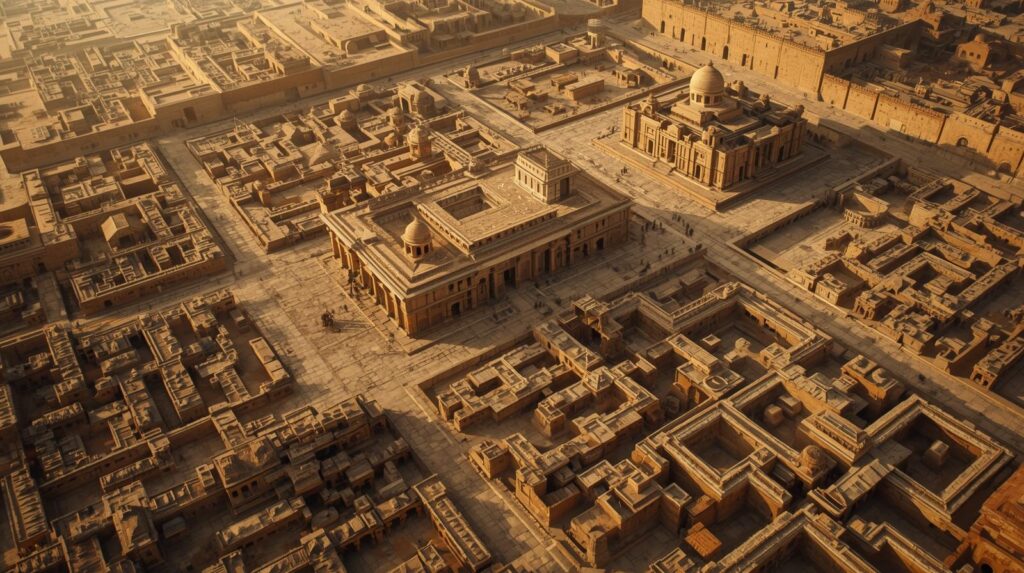

2. Urban Planning & Architecture — The Civic Mind of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

One of the most striking features of Harappan cities is their unmistakable demonstration of premeditated urban design. Unlike settlements that grow haphazardly, Harappa and Mohenjo-daro show planners’ intentions: broad, rectilinear streets laid out on a grid; clear separations between elevated citadel areas and lower residential quarters; and organized blocks that suggest zoning for craft, storage, and living. This chapter explores the physical systems — bricks, streets, drains, public buildings, and houses — and the social logic they imply.

2.1 Grid layout and street networks

The street systems reveal a deliberate grid pattern. Major avenues run straight and wide, intersected by narrower lanes that serve household access. This orthogonal planning improves circulation, ventilation, and the movement of goods. Public buildings and warehouses often fronted onto principal roads, which made access for markets and administration efficient. From an urbanist’s perspective, such an arrangement reduces congestion, enables rapid response to emergencies, and organizes land use in a way that remains familiar to modern planners.

2.1.1 Functional logic of intersections and blocks

Blocks appear to be self-contained units with internal courtyards and workshops; intersections were nodes that connected different economic activities. Streets also guided drainage and waste disposal, with thresholds and ramps indicating conscious efforts to manage human and cart traffic separately. In short, the grid is not merely geometrical beauty — it is civic engineering designed to support everyday life at scale.

2.2 Standardized bricks and construction techniques

Harappan builders used standardized baked bricks with remarkably consistent proportions. Researchers have noted recurring ratios in brick dimensions, which aided modular construction, repair, and interchangeability. Walls, platforms, and public structures used these uniform units to create durable buildings resistant to seasonal flooding and weathering. The prevalence of fired bricks (rather than sun-dried mud-bricks alone) suggests investment in infrastructure longevity and communal standards for building materials.

Beyond bricks, skilled masonry, brick bonding patterns, and compacted earthen platforms feature across sites. Foundation planning — often a raised citadel on compacted layers — protected the most important civic buildings from inundation, indicating an understanding of environmental risk and the means to mitigate it.

2.3 Water management and sanitation — civil engineering in practice

Arguably the Harappans’ most advanced contribution to urban living was their water and sanitation systems. Individual houses had access to drains that connected to covered street sewers. Many homes contained wells and bathing platforms; public baths and communal reservoirs demonstrate organized water provisioning. Covered drains with inspection slabs, masonry channels, and careful gradients show an integrated approach to waste removal—an approach that preserved public health and kept living streets dry and usable.

2.3.1 Technical features of Harappan drainage

Drains were typically built of brick or stone and terminated in larger channels that ran along streets. In several sites, sluices and stepped outlets suggest control points where flows could be inspected or diverted. This degree of hydraulic planning is sophisticated for its time and indicates both civic oversight and skilled artisanry working in tandem.

2.4 Public architecture: baths, granaries, and citadels

The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is the most iconic public structure: a waterproofed tank framed by steps and chambers, suggesting ritual, hygiene, or civic ceremony. Similarly, large granary-like structures and magazine complexes imply organized food storage or redistribution. Citadel platforms housed larger, more monumental buildings — perhaps administrative or ceremonial — set above the level of ordinary dwellings. Together, these structures reveal cities designed for shared life, not just individual households.

2.5 Residential design: courtyards, workshops, and mixed uses

House plans often centered on courtyards, giving light and ventilation while providing private workspaces around them. Multi-room houses sometimes contained small kilns or craft areas, showing that domestic production was integrated into daily life. This mix of living and working spaces created resilient neighbourhood economies and kept artisan skills embedded within the fabric of the city.

2.6 A short personal reflection on built intelligence

When I first studied Harappan house-plans in a museum catalogue, I was struck by how the same priorities — comfort, hygiene, and resilience — guided planners 4,000 years ago as they guide us today. What felt most inspiring was the implicit civic ethic: building for durability, for community use, and for predictable maintenance. That ethos, embedded in bricks and drains, is one of the clearest lessons ancient cities offer modern urban designers.

In sum, Harappan urbanism combines geometric clarity, material discipline, and civic engineering. Its legacy is not only archaeological curiosity but a set of pragmatic solutions to perennial urban problems: circulation, sanitation, flood risk, and mixed-use neighbourhoods. These solutions remain relevant — and surprisingly modern — in their logic and intent.

4. Art, Script, and Sculpture — Expressions of the Indus World

The Indus cities expressed a refined visual and symbolic language through small-scale objects: seals, beads, pottery, and metal figurines. These artefacts are not merely decorative; they reveal identity, belief, and commercial practice. Whether engraved on a steatite seal or modelled in terracotta, the craftsmanship shows technical mastery and an eye for proportion, pattern, and repeated motifs that communicated meaning across households and trade networks.

4.1 Seals and symbolic imagery

Harappan seals are miniature masterpieces—carefully carved steatite plaques typically stamped with animal motifs, trees, and short sequences of signs. Their imagery includes bulls, unicorn-like composite creatures, and stylized trees, often accompanied by a short string of undetermined signs. While the exact semantics remain debated, seals clearly functioned as markers of ownership, commercial tokens, or identity emblems. The recurrence of motifs suggests shared iconography and possibly clan or craft identifiers used across the region.

4.2 Script — an undeciphered puzzle

Short, linear sequences of signs appear on seals, pottery, and small objects and are commonly referred to as the Indus script. The inscriptions are brief—often only a handful of symbols—and no bilingual inscription has yet been discovered to anchor decipherment. Consequently, the script remains undeciphered, though its patterned use strongly implies a conventional writing system connected to trade, administration, or ritual practice.

4.3 Sculpture and metalwork

Sculpture ranges from small terracotta figurines to finely-cast bronze works. The celebrated Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro—a slim bronze figure with a confident pose—demonstrates sophisticated alloying and lost-wax casting techniques. Other sculptures, including male figures and animal representations, show attention to posture, ornament, and dress. Metalwork, beads, and inlaid stone jewellery indicate both local aesthetic practices and materials acquired through long-distance trade.

4.4 Design, colour, and everyday aesthetics

Painted pottery with geometric patterns, polished faience beads, and incised motifs show that beauty was integrated into everyday objects. Design choices—repetition, symmetry, and stylised natural forms—suggest a coherent aesthetic sensibility that bridged ritual objects and domestic wares. In short, the Indus artistic tradition combined utility with visual language, making objects both useful and meaning-bearing.

Overall, the Indus art and material signs form a complementary system: seals and script link to identity and exchange, while sculpture and craft reflect daily life, ritual, and aesthetic preference. Together they offer a vivid, if partly enigmatic, portrait of a cultured urban world.

5. Health and Sanitation — Public Awareness in the Indus Cities

The cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro demonstrated an extraordinary concern for public health and hygiene. Archaeological remains of covered drains, household wells, bathing platforms, and public baths show that water management and sanitation were central to urban planning. These innovations helped prevent disease, maintained environmental cleanliness, and supported an organized civic lifestyle nearly 5,000 years ago.

5.1 Domestic sanitation — wells, drains, and household bathing

Most residential blocks had private or shared wells that provided clean water for daily use. Almost every house had a bathing area or small paved platform with a sloped floor leading to a drain. These household drains connected to the larger municipal sewer system, ensuring that wastewater did not stagnate near living quarters. Such attention to domestic hygiene was unmatched in contemporary civilizations of the same era.

5.2 Public water facilities — the Great Bath and community wells

The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro stands as the earliest known example of a public bathing structure. Its watertight brick tank, steps, and adjoining rooms suggest both ritual and hygienic use. Large community wells and reservoirs across neighborhoods ensured equitable water access, reflecting not only technical skill but also a sense of collective responsibility for cleanliness. These shared facilities likely strengthened social cohesion through common practices of bathing and purification.

5.3 Sewage systems — covered drains and inspection slabs

The Indus cities featured covered street drains constructed of brick, often with stone or baked brick lids that could be removed for cleaning. Inspection points and gradient control reveal engineering awareness of water flow and maintenance needs. These systems carried wastewater from homes into larger channels, preventing contamination and ensuring efficient drainage even during floods or monsoon rains.

5.4 Lessons in public health and urban design

The sophistication of these sanitation systems highlights a vital civic principle: health depends on shared infrastructure and collective responsibility. Cleanliness was not treated as a private matter but as a public priority integrated into architecture. The economic and social benefits—reduced disease, increased productivity, and enhanced quality of life—were clearly understood and institutionally supported.

5.5 Personal reflection — ancient inspiration for modern cities

Studying these ancient water and waste systems taught me that design and discipline go hand in hand. Modern urban challenges—pollution, waste management, and water scarcity—could be better managed if we revived this civic mindset. The Indus people remind us that lasting progress requires maintenance culture as much as innovation.

In conclusion, the health and sanitation systems of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro were not isolated feats of engineering; they were social technologies ensuring communal wellbeing. Their integrated design offers timeless lessons for sustainable urban living today.

6. Lost Questions and Unanswered Thoughts — The Mystery of the Indus Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization remains one of history’s most captivating enigmas. Despite decades of excavation and research, several questions continue to puzzle scholars. Foremost among them is — why did this advanced civilization decline so suddenly? Was it a result of natural disasters, climate change, river shifts, or invasions? Or did the system gradually collapse under its own ecological and economic pressures? The truth, as of today, remains elusive.

6.1 The enigma of decline

Archaeological evidence suggests that around 1900 BCE, the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro began to shrink in size and population. Many researchers attribute this to the drying or shifting of river systems such as the Ghaggar-Hakra (possibly the ancient Saraswati). Others point to changing monsoon patterns, floods, or declining trade networks that weakened the urban economy. Some theories even invoke migration or cultural transformation rather than abrupt destruction. Yet, no single explanation fits all sites — the mystery persists.

6.2 The undeciphered script — a civilization without a voice

The Indus script remains unread, leaving us without direct access to the people’s thoughts, beliefs, or names. Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, the Indus world has left no deciphered texts to tell its story. Their language, administration, and myths remain silent — preserved only through material symbols on seals and pottery. This silence is both frustrating and poetic: a civilization that speaks through its architecture and artefacts, but whose written voice remains locked away.

6.3 Personal reflection — learning from the silence of history

For me, the mystery of Harappa is not only historical but philosophical. It reminds us that even the most advanced societies can fade if they lose balance with nature or one another. The collapse of the Indus world is not merely an ending — it is a mirror that reflects the fragility of human achievement. Their lost script, like a whisper across time, tells us that sustainability and harmony are the true markers of progress.

These unanswered questions keep the Indus Civilization alive in our imagination. Perhaps their greatest legacy lies in this very mystery — a reminder that knowledge and humility must coexist, and that history’s silence sometimes speaks the loudest truths.

7. Personal Learnings — From Harappa and Mohenjo-daro to Modern Life

Reading about Harappa and Mohenjo-daro was not just an academic exercise for me; it changed how I think about planning, community, and durability. These ancient cities taught me that civilization is measured less by monuments and more by the systems and values that keep everyday life functional, fair, and sustainable. The lessons below are practical takeaways I now try to apply in my work and daily life.

7.1 The power of planning and discipline

The Harappan commitment to standardized bricks, orderly streets, and deliberate layouts shows a belief in prior planning. They planned for maintenance and repair as much as for construction. This reminded me that good outcomes begin long before execution—through clear plans, standards, and discipline. In projects I manage today, a small upfront investment in standards often prevents large future costs.

7.2 Community and shared responsibility

Shared wells, public baths, and uniform neighbourhood patterns show that Harappan life relied on collective practices. That highlighted for me the importance of community systems: shared infrastructure works best when people see themselves as stakeholders. In modern contexts—whether neighbourhood initiatives or workplace processes—cultivating a sense of joint responsibility improves resilience and fairness.

7.3 Hygiene as a civic value

The scale and care of Harappan sanitation systems taught me that cleanliness was considered civic work, not merely a private habit. That view reshaped how I approach public health and workplace hygiene: systems, simple rules, and maintenance culture matter as much as technology.

7.4 Living in balance with the environment

The Indus people adapted to their rivers and monsoon cycles—and yet their decline also warns that environmental shifts can undo human plans. This has made me more mindful of sustainability: design decisions must respect natural limits and include contingency for changing conditions.

7.5 Humility and long-term perspective

Perhaps the most profound lesson is humility. A society can be advanced in many ways yet remain vulnerable. Harappa’s story is a reminder to value long-term stability over short-term gain, and to build institutions that endure rather than just impress.

In short, Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are not only historical sites but living lessons: plan carefully, share responsibility, invest in basic civic systems, respect the environment, and remain humble about human limits. Applying these principles can make modern projects and communities more resilient and humane.

Conclusion — Enduring Lessons from Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are not merely archaeological sites; they are enduring arguments about what makes a city resilient, humane, and sustainable. Their ruins teach us that the strength of a civilisation lies not only in monumental architecture or military power but in the everyday systems that organise life: planned streets, reliable water, shared norms, standardised materials, and mechanisms for storing and distributing essential goods. These elements together produce social stability over generations. For contemporary planners, civic leaders, and thoughtful citizens, the Indus cities offer more than historical curiosity — they provide practical models for building communities that endure.

One clear takeaway is the value of integrated planning. Harappan towns were planned at multiple scales: individual houses with internal drains, neighbourhood blocks with communal wells, and city-wide systems for drainage and flood management. This multi-layered design anticipates modern ideas of resilience: redundancy, clear responsibilities, and maintenance. When infrastructure design anticipates daily use and long-term wear, cities function better and recover more quickly from shocks. The Indus example encourages us to think beyond one-off projects and invest in systems that can be maintained and adapted.

Another important lesson is the potency of standardisation. Uniform brick sizes, standardized weights, and repeated building patterns made construction, repair, and commerce more efficient and predictable. Small standards—consistent materials, shared measurements, clear naming or marking systems—translate into large-scale reliability. For contemporary practice, this argues for the disciplined adoption of standards in construction, procurement, and public service delivery to reduce friction, lower costs, and increase transparency.

Harappan cities also emphasise that public health is civic infrastructure. The elaborate drains, household sanitation, community wells, and public baths show a commitment to hygiene institutionalised through design. Clean water and effective sewage were not treated as optional amenities but as essential public goods that required collective effort. Today’s urban policies would benefit from that perspective: treating sanitation, clean water, and routine maintenance as investments that yield long-term social and economic returns rather than as recurring expenditures to be deferred.

The economic life of the Indus world offers a third lesson: diversified, interconnected economies are more resilient. The Harappan economy combined local agriculture, household craft production, organised storage, and extensive trade networks. This blend of household-level production and city-scale coordination supported livelihoods and allowed cities to interact with distant regions. Modern economies, too, become brittle when overly specialised or when local production is entirely replaced by distant supply chains. The Indus model suggests a balance: foster local skills and small producers while maintaining fair, transparent systems for inter-regional exchange.

Culturally, the artifacts—seals, figurines, jewellery—remind us that aesthetics and meaning matter. Everyday objects bore design and symbolic language; aesthetic choices were woven into ordinary life. This integration of beauty and function implies that communities that care for meaning, identity, and shared symbols often cultivate stronger social bonds. Civic design that respects local identities and embeds cultural expression into public life can strengthen civic pride and cooperation.

Yet the Indus story is also a cautionary tale. The causes of decline—environmental shifts, changing rivers, altered monsoons, and disrupted trade—suggest that even well-organised societies can be vulnerable to ecological and systemic shocks. The unresolved questions about the script and administration further remind us that silent records leave gaps in our understanding; resilience requires both physical infrastructure and adaptable social institutions. Modern planners should therefore combine engineered solutions with flexible governance, contingency planning, and continuous learning mechanisms.

On a personal level, the Indus legacy has practical implications for how we live and work. From the Harappan example I adopt three habits: (1) plan with maintenance in mind, not just completion; (2) favour simple standards that everyone can follow; and (3) treat shared resources—water, streets, public spaces—as collective responsibilities rather than purely private conveniences. These small shifts in attitude and practice compound over time to produce healthier, more equitable communities.

Finally, the Indus cities invite humility. Their ruins show the heights human organisation can reach and the fragility that accompanies it. They urge us to measure progress not only by technical capability but by the sustainability and fairness of systems we build. If modern societies take seriously the lessons of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro—integrated planning, standardisation, investment in public health, balanced economies, cultural embedding, and governance for uncertainty—we stand a better chance of creating cities that serve people across generations.

In sum: Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are blueprints of civic intelligence. They teach that durable civilisation rests on daily, practical decisions—how we lay our streets, manage our water, set our standards, and share responsibilities. These are actions any community can start today to shape a more resilient, humane future.

References

Below are reliable and useful reference examples for Harappa and Mohenjo-daro (Indus Valley Civilization). Replace the placeholder URLs with actual links (UNESCO, ASI, museum pages, academic books/articles) or convert these entries to your preferred citation style (APA / MLA / Chicago).

- UNESCO — Indus Valley Civilization / Harappa & Mohenjo-daro

Authority: UNESCO overview pages and site dossiers.

[Add link to UNESCO page] - Archaeological Survey of India — Excavation Reports

Authority: ASI excavation reports and site summaries (Harappa, Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, etc.).

[Add link to ASI reports] - John Marshall — Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization

Classic monograph documenting early excavations and interpretations.

[Add bibliographic link] - Gregory L. Possehl — The Indus Civilization

Comprehensive modern overview and synthesis.

[Add link or DOI] - Rita P. Wright — The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society

Selected chapters on urban life and social organization.

[Add link or library record] - Lothal and Maritime Trade — Journal Articles / Excavation Papers

Research on coastal trade, harbour facilities, and maritime networks.

[Add article links] - Recent Excavations — Rakhigarhi / Dholavira (Indian archaeological journals)

Latest site reports, dating revisions, and updated interpretations.

[Add recent reports] - Museum Collections — National Museum (New Delhi), British Museum, Pakistan Museum

Catalogue pages for seals, figurines, and exhibition items.

[Add museum collection links] - Archaeobotanical & Geoarchaeological Studies — Climate / River Shift Papers

Studies on environmental change, river dynamics (Ghaggar-Hakra), and impact on settlement.

[Add scientific papers or DOIs] - Educational Resources — Khan Academy / Encyclopedia Britannica / University Lectures

Accessible overviews and lecture series for students and general readers.

[Add educational links]

3. Social and Economic Life — The Flourishing World of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

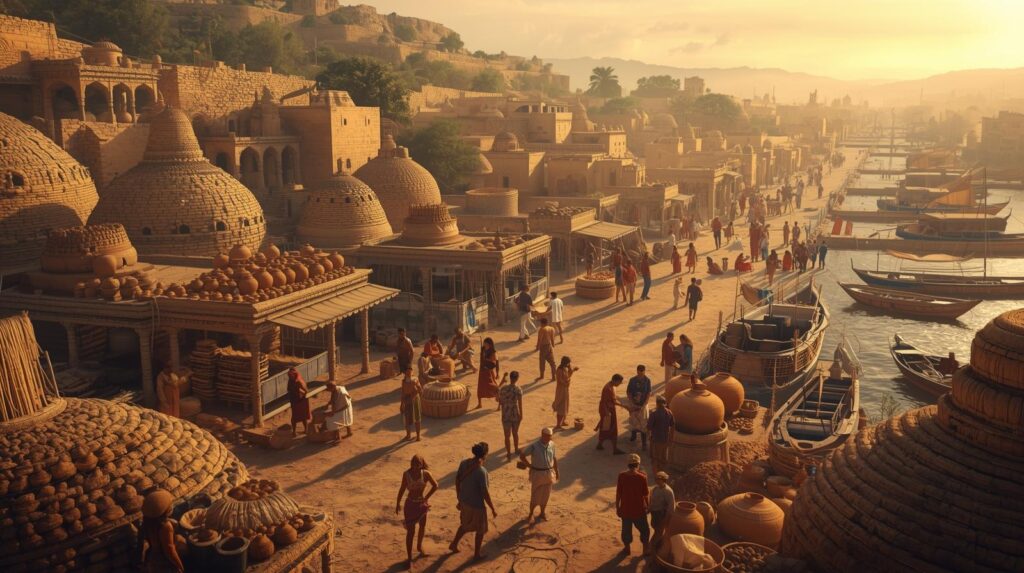

The Harappan cities were not just feats of engineering; they were living social systems with complex economic networks, shared cultural practices, and organized civic life. The material remains — houses, seals, craft workshops, granaries, and port facilities — point to an economy that combined agriculture, artisanal production, and long-distance trade. Equally important are the social traces: household organisation, gendered iconography, and collective institutions that made daily life coherent and resilient.

3.1 Social structure and daily life

Evidence suggests a society structured around specialised roles but not rigid caste hierarchies as later texts describe. People seem to have been organised into households, neighbourhoods, and craft communities. The presence of multi-room houses with courtyards indicates family-centred living where domestic production—textiles, bead-making, metalworking—often took place within or adjacent to residences. Public amenities such as wells and baths, and the uniformity of house-plans across neighbourhoods, imply shared values around hygiene, access to resources, and civic responsibility.

Artistic representations, particularly terracotta figurines and female statuettes, point to the presence of goddess motifs and fertility imagery. While it is risky to map later social categories onto ancient societies, these images suggest important roles for women in ritual life and possibly in economic production. Rather than viewing social life purely in hierarchical terms, the Harappan evidence often highlights cooperation—neighbourhood-level collaboration in water management, craft specialization shared across households, and collective maintenance of public drains and streets.

3.2 Agriculture, food production and storage

Agriculture formed the economic backbone of the Indus settlements. Archaeobotanical evidence shows cultivation of cereals such as wheat and barley, pulses, oilseeds, and notably cotton, which was used for textiles. Irrigation, possibly in the form of canal networks and water conservation measures, supported crop yields, while wells and reservoirs supplied neighbourhoods with potable water.

The existence of large granary-like structures at several sites indicates systematic food collection and storage. These granaries, often situated near civic centres or along principal streets, suggest coordinated management of surplus — whether for redistribution, long-term storage against famine, or for trade. Such organised provisioning points to administrative oversight and a degree of social planning that sustained urban populations.

3.2.1 Seasonal rhythms and urban provisioning

Crop cycles and seasonal floods likely shaped labour patterns and market rhythms. During harvest seasons, craft production may have scaled down to accommodate agricultural labour, and surplus grain may have been channeled into trade. Urban provisioning systems, including coordinated storage and the physical logistics of moving grain to and from warehouses, indicate planning that connected rural production with urban demand.

3.3 Craft production and artisanal organisations

Harappan artisans produced a wide range of goods: pottery, stone and faience beads, shell and copper ornaments, bronze tools, and seals engraved with motifs and short inscriptions. Workshops and evidence of specialized toolkits reveal high levels of skill and division of labour. Bead-making, for example, involved sequential operations—drilling, shaping, polishing—that often required specialised workspaces and trained hands.

The distribution of finished goods—both locally and across distant markets—shows organised production networks. Standardized weights and measures recovered from multiple sites enabled predictable trade practices and quality control. These measurable systems indicate trust and repeatability in commercial exchanges, essential foundations for market integration.

3.4 Trade networks: regional and long-distance connections

Harappan trade was both regional and international. Archaeological finds suggest commercial ties stretching to Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Iranian plateau. Exotic materials—lapis lazuli, marine shells, and certain metals—not locally available, appear in Harappan contexts, pointing to exchange routes by river and sea. Ports and docking facilities at harbour sites like the port-city of Lothal (on the Gujarat coast) demonstrate maritime trade and a capacity to engage in trans-regional commerce.

Local markets and craft clusters facilitated daily exchange of food, tools, and manufactured goods, while long-distance trade brought prestige items and raw materials that fed urban craft industries. The Harappan economic system combined household-level production with city-wide commercial coordination—an efficient hybrid that supported urban complexity.

3.5 Seals, accounting and indicators of administration

Seals—small, carved steatite objects stamped with animal motifs and short inscriptions—functioned as identifiers in trade and administrative transactions. Their consistent imagery and careful manufacture suggest they were used to mark ownership, consignments, or goods. Alongside standardized weights and measures, seals point to record-keeping and a public culture of transactions that required oversight.

Although we lack deciphered textual records, the material systems—seals, weights, granaries, and standardized architecture—create a mosaic of administrative practice. Rather than a literate bureaucracy as we might imagine from later states, the Harappan administration seems to have relied on material protocols and civic infrastructure to govern economic life.

3.6 Religion, ritual and cultural expression

Religious practice appears woven into daily life. Shrines, ritual objects, and figurines indicate community rituals centred on fertility, water, and animal symbolism. Many motifs on seals—unicorn-like figures, bulls, and trees—may have had protective or identity functions. Ritual practices likely supported social cohesion and legitimised communal investments such as granaries and public baths.

3.7 A personal note — lessons from an ancient economy

Studying Harappan social and economic life reminds me how urban prosperity depends on invisible systems: trust, measurement, shared norms, and coordinated infrastructure. In a modern project I worked on, adopting simple standard measures and clear communal responsibilities for water and waste dramatically improved outcomes—an echo of Harappan priorities. Their blend of household-scale craft and city-scale organisation offers useful models for resilient, community-centred urban economies today.

In sum, the social and economic fabric of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro combined agricultural surplus, skilled production, and extensive exchange with a civic ethos that emphasised shared management of resources. Together these elements supported cities that were economically dynamic, socially cohesive, and culturally expressive.