History is not always found in books—it often lies buried beneath the soil, preserved in broken pottery, stone fragments, and silent monuments that whisper tales of forgotten civilizations. When I first began studying archaeology, I did not see it as a mere academic subject; it felt like a personal quest—a journey into the layers of time to understand how humanity evolved, thought, and remembered. As a student, the pages of history once seemed distant and dry, but as I walked through excavation sites, brushed off dust from an ancient shard, and stared at inscriptions carved thousands of years ago, history began to breathe—it became alive, real, and deeply human.

During my university years, my research on the “Tradition of Historical Writing in India” changed the way I perceived the past. I discovered that the Indian tradition of historiography was never limited to chronicling dates and rulers; it was a philosophical reflection of our collective consciousness. From the Vedic hymns and Buddhist chronicles to Megasthenes’ accounts and colonial-era interpretations, the way we wrote history evolved with every era. Archaeology became the bridge that connected textual history with tangible reality. Each artifact unearthed from the ground told a story that words alone could not capture—a story of human resilience, creativity, and continuity.

Through my field experiences, I learned that the tradition of historical writing is not a static process—it is a dialogue between the past and the present. Archaeology taught me that every object, no matter how ordinary it may seem, carries within it the essence of an age gone by. It taught me patience, curiosity, and respect for evidence. This understanding reshaped my vision as a researcher and a writer: history, I realized, is not just about recording events—it is about feeling the pulse of humanity across time. In this article, I share my journey through education, fieldwork, and reflection, exploring how archaeology continues to redefine the art and purpose of writing history in our modern world.

1. The Historical Context of the Tradition

1.1 Roots of Indian Historical Writing

When we speak of the “tradition of historical writing,” we are not merely talking about recording facts from the past — we are talking about a living intellectual dialogue that has continued for thousands of years. In India, history was never just a record of kings and wars; it was a reflection of the philosophical and cultural consciousness of society. The ancient traditions of shruti and smriti, the epic narratives of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the Buddhist and Jain chronicles all reflect a deep-rooted historical awareness. Though these texts may not follow chronological or modern historiographical methods, they preserve an authentic sense of time, ethics, and experience — painting vivid pictures of social life, political order, and cultural values.

From sage Vyasa to poet Kalidasa, and later to Banabhatta, who wrote Harshacharita, Indian writers perceived history not as a sequence of political events, but as an experiential philosophy. This differs from the Western notion of history, which often emphasized timelines, empires, and conquests. In Indian tradition, history included moral, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of human life. This worldview later laid the foundation for how archaeology and historical research would evolve in India — as a blend of material evidence and philosophical understanding.

1.2 Colonial Period and the Reinterpretation of History

The nineteenth century marked a turning point in India’s historiography. When British administrators and scholars began studying the Indian past, they introduced European methodologies and frameworks to define it. Figures like William Jones, Alexander Cunningham, and James Prinsep pioneered the study of India’s inscriptions, monuments, and ancient sites. Their efforts formalized the disciplines of epigraphy and archaeology in India and gave rise to what we now call “modern Indian historiography.”

While their work was methodical and scientific, it also carried the biases of the colonial perspective. India’s civilization was often portrayed as glorious in the past but decayed in the present. In response, Indian historians such as R. C. Majumdar, K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, and Dr. Radhakumud Mukherjee began to reclaim the Indian viewpoint. They argued that India’s history was not merely a political chronology but a record of ideas, cultural creativity, and spiritual evolution. This intellectual revival sought to restore balance — to see the past through Indian eyes while maintaining the rigor of modern research.

1.3 Archaeology: The Silent Language of History

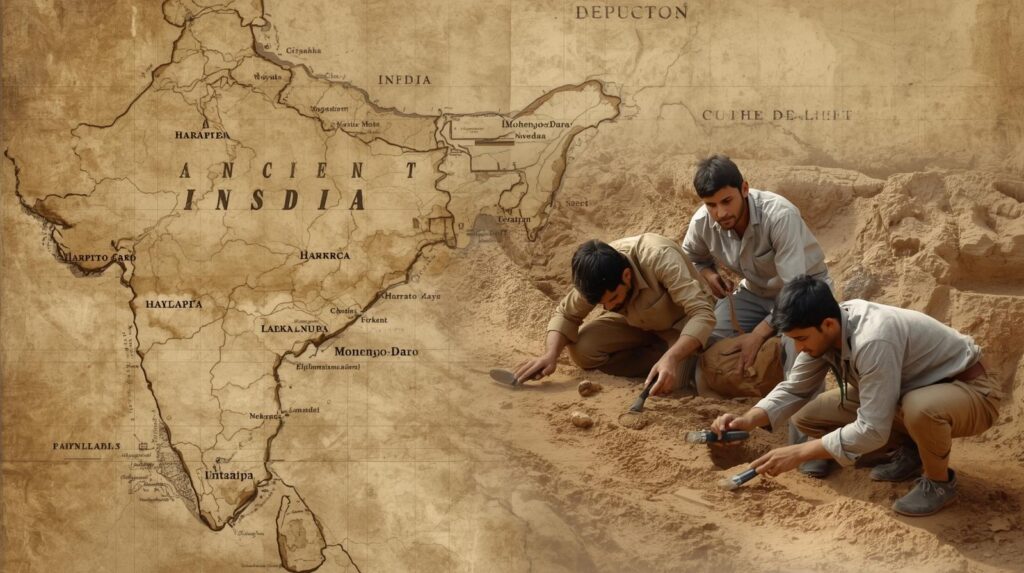

Archaeology became a decisive force in reshaping our understanding of history. The discoveries of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa changed the very timeline of Indian civilization, revealing that the subcontinent’s urban culture existed thousands of years before previously thought. The soil began to speak where the texts were silent. Excavated artifacts, pottery, seals, and inscriptions offered tangible proof that history was not confined to manuscripts — it was alive beneath our feet.

For me, this realization was deeply moving. Every brick, sculpture, and inscription seemed like a sentence from the past, waiting to be read with care and sensitivity. While working on excavation sites, I felt that archaeology speaks a “silent language” — one more powerful than words. When a hidden inscription emerges from beneath a ruined temple or an ancient coin surfaces from the dust, it is not merely a discovery; it is a dialogue with time itself — a reminder that our civilization has always been in conversation with its own memory.

1.4 Modern Perspectives and Continuity

Today, history writing has become a multidisciplinary pursuit. Historians, archaeologists, sociologists, and anthropologists collaborate to interpret the past from multiple angles. Modern tools such as digital imaging, satellite mapping, and GIS analysis have elevated archaeology into a scientific art. Yet, amid all these advancements, the essence of the Indian tradition — seeing history as an experience rather than just data — continues to endure.

This enduring tradition teaches us that history is not merely about the past; it is a way to understand the soul of the present. The fusion of archaeology and historical writing is not just about reconstructing what was lost — it is about rediscovering meaning, identity, and continuity. That is the true “historical context of the tradition” — a bridge between knowledge, experience, and discovery that continues to guide both scholars and seekers alike.

2. My Education and the Transformation of My Perspective

2.1 The Journey from Learning to Awareness

For me, the study of history was never just about memorizing dates and events—it was a process of understanding existence itself. When I chose “History and Archaeology” as my major at university, I was simply curious about the past. But as my studies deepened, I realized that history is not merely a record of what happened; it is a lens through which we understand who we are today. My professors often said that the true purpose of history is not just “to know,” but “to comprehend,” and that comprehension requires sensitivity, curiosity, and respect for evidence.

During my undergraduate years, I studied the “Tradition of Historical Writing in India” in detail. Reading scholars like R.C. Majumdar, Romila Thapar, and Irfan Habib made me realize how every historical perspective is shaped by its social and political context. This understanding became a turning point for me—it showed that no historian, however objective, can be entirely detached from the world they live in. The more I read, the more I understood that history is not just a discipline; it is a dialogue between the observer and the observed.

2.2 Lessons from Research and Archaeology

During my postgraduate research, I chose the topic “Ancient Urban Civilizations and Inscriptions of Rajasthan: A Social Study.” That was the first time I got the opportunity to engage in real fieldwork. Initially, it felt like an academic assignment, but the moment I began excavating around ancient temple sites and discovered fragments of pottery, coins, and inscriptions, I realized that history breathes beneath the soil—it lives in silence and dust.

I still remember one moment vividly: during an excavation in the Jhunjhunu district, our team found a copper plate inscribed in early Brahmi script. Holding that artifact in my hands was a deeply emotional experience—it was as if a voice from thousands of years ago was speaking directly to me. In that instant, I wasn’t just “reading” the past; I was “conversing” with it. That moment transformed my vision completely. I no longer saw history as a chain of events, but as a continuous evolution of human consciousness.

2.3 How Education Transformed My Writing

The academic environment I was part of did more than teach me research methods—it taught me the ethics of expression. I learned that historical writing is not about transmitting information; it’s about building a dialogue with the reader. I began to adopt a narrative approach in my writing, blending analytical facts with human stories. One of my mentors once told me, “If history doesn’t evoke an emotional response in the reader, it remains information, not knowledge.” That sentence became a guiding principle for my entire writing journey.

Gradually, my writing found a balance between research and empathy. I realized that the true value of archaeology and historical writing lies in connecting people with their own roots. That’s why, in my articles and presentations, I don’t merely list facts; I try to uncover the emotions and stories behind them. Education taught me that the study of history never truly ends—it is an endless journey where every discovery raises a new question and every question opens a new window into human understanding.

2.4 Expanding Vision: From Past to Present

My education and field experiences taught me that there is no wall between the past and the present—they complement and define each other. Understanding the past helps us interpret the present with greater depth and awareness. This realization continues to inspire me even today: that history should not be seen merely as a subject of study, but as a guide for life itself.

Whenever I write about history or archaeology now, I still feel like that same student who once held a fragment of ancient earth in his hands. That moment became the foundation of my vision—a reminder that education doesn’t just provide knowledge; it provides perspective. And that perspective, I believe, is the soul of historical writing: it teaches us that the study of the past is, in truth, the key to understanding the future.

3. Field Stories: A Series of Experiences

3.1 History Beneath the Sand — My First Excavation

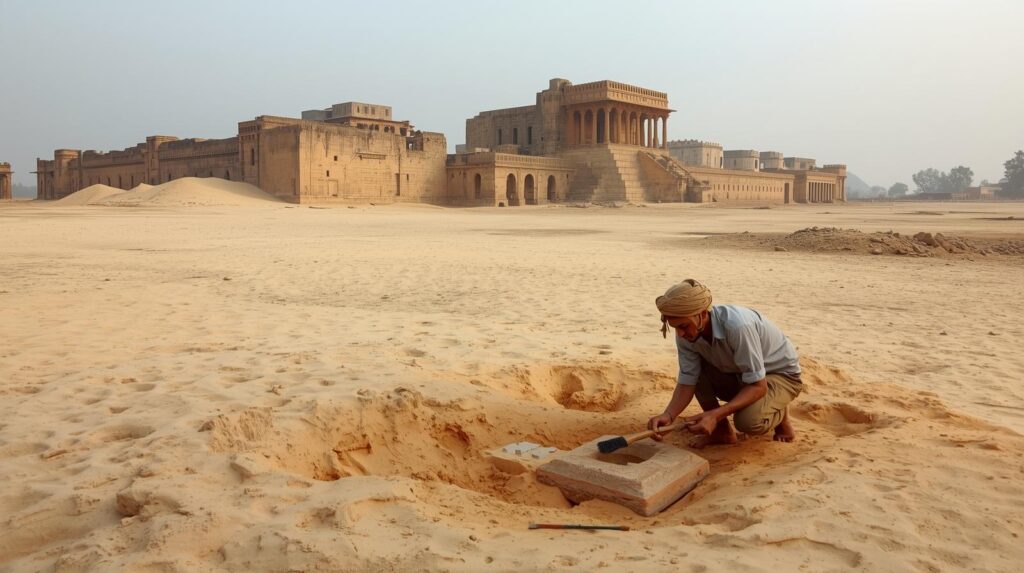

Location: Nagargarh, Rajasthan | Year: 2017

It was the day when history leapt out of textbooks and settled into the palms of my hands. In a small town called Nagargarh, Rajasthan, our team had begun an excavation project at an ancient mound. It was my very first field assignment, and I remember feeling a mixture of excitement and nervousness. As the cool morning breeze brushed against the sand, I realized that I wasn’t just digging soil — I was uncovering a forgotten story.

For the first few hours, we found only broken pieces of brick and stone. But by noon, one of my teammates shouted, “Sir, I think we found something!” Carefully brushing away the dust, we unearthed a small earthen pot. It looked simple, but its shape and texture revealed an ancient craftsmanship. Our supervisor examined it and estimated that it dated back to around the 2nd century BCE. In that moment, the pot no longer seemed like an object — it became a witness to a civilization that once lived, dreamed, and created.

That evening, as I walked back from the site, I felt a strange calmness within me. I realized that history is not merely studied; it is discovered — and sometimes, that discovery reflects the deepest layers of our own soul. That day became my first true breath of archaeology, a moment that forever changed the direction of my thinking.

3.2 A Conversation with the Earth — When Time Answered Back

Location: Jhunjhunu District | Year: 2019

During my research years, I was assigned to study the remnants of an ancient temple in a small village in the Jhunjhunu district. To the villagers, the site was ordinary, but to me, it was a mystery waiting to be unraveled. As we began digging near the temple’s foundation, we discovered a stone plaque inscribed with early Brahmi script. My heart started pounding — were we about to hear the voice of a forgotten age?

We made an impression of the inscription and later analyzed it in our university lab. The translation revealed that it mentioned a ruler who had built a resting house near a riverbank for travelers and monks. What astonished me was that this detail perfectly matched the oral traditions of the local community. It was as if the past was confirming its own story through the soil.

That discovery taught me that archaeology is not merely about finding artifacts — it’s about building bridges between evidence and memory. That humble stone plaque became a symbol of continuity, linking legends, inscriptions, and people’s lives together. It convinced me that history is not a silent past but a living dialogue, constantly resurfacing when we choose to listen.

3.3 The Past Hidden in Village Walls — Encountering Living Traditions

Location: Bugala Village, Jhunjhunu | Year: 2021

My third and most impactful field experience took place in Bugala village, where I studied the traces of history preserved in folk architecture and oral traditions. The elders of the village told me that an old mansion was built using “ancient bricks” taken from a nearby ruined temple. Their curiosity and stories drew me in, and I decided to investigate.

When we examined the structure, we found that several bricks indeed had carvings resembling ancient temple motifs. After careful observation, I concluded that these materials likely belonged to a 10th-century construction. This small yet revealing observation showed me how rural spaces continue to preserve the past — often unknowingly — through everyday architecture and collective memory.

That day I realized that history’s greatest power lies in its ability to survive within people, places, and traditions. It does not live only in inscriptions or museums; it lives in songs, in rituals, in the walls built by generations. Every village, every wall, and every story holds a silent archive — all we need is the sensitivity to listen.

When I later included these three experiences in my research paper, I understood that fieldwork is not just a scientific practice — it is also a spiritual experience. The soil, the stones, and the scripts don’t merely reveal data; they whisper meaning. They connect us not just with the past, but with our own sense of belonging in the present. That, to me, is the true lesson of field stories — history is not only discovered; it is felt.

4. Methodology and Source Management

4.1 From Field Notes to a Finished Article

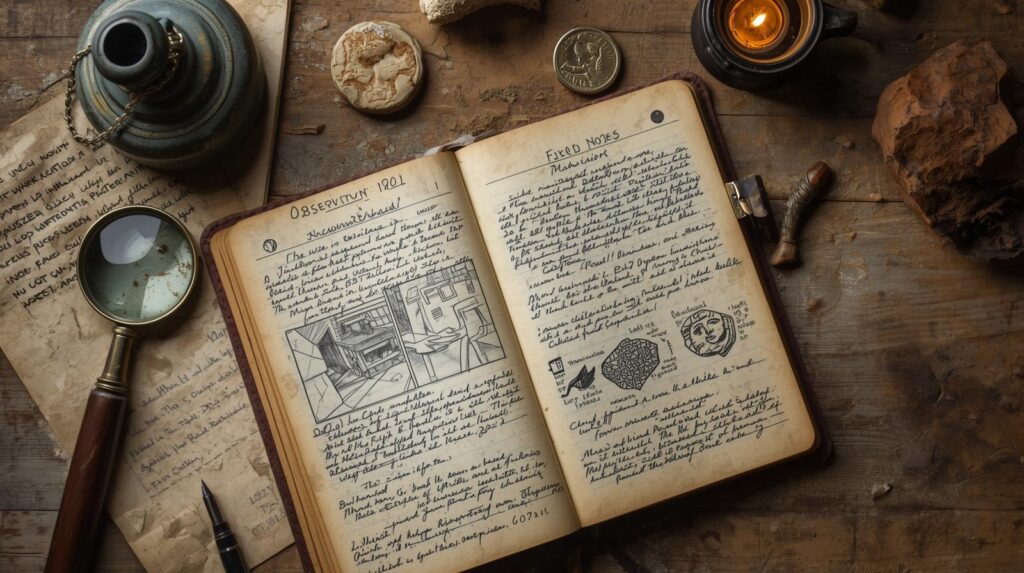

For every archaeologist, writing is a sacred process — because what the soil and stones cannot say in words, we must express through language. When I return from the field, I don’t just bring artifacts with me; I bring stories, contexts, and experiences. Organizing these experiences into coherent narratives is the first step of historical writing.

My process always begins with detailed field notes. During excavations, every observation — the sequence of soil layers, the direction of artifacts, their texture, color, and depth — is carefully recorded. These notes are not mere data; they are the language through which the past communicates. My field diary is not just a notebook — it is the first draft of living history. Whenever I revisit those pages, I can almost feel the atmosphere of the site again — the scent of the dust, the stillness of the moment, and the whisper of time itself.

In the next stage, I attempt to connect the factual data with human experience. The purpose of my writing is not merely to convey information but to explore how each piece of evidence reveals human thought, belief, and social structure. This is where archaeology and historical writing meet — one provides science, the other provides sensitivity.

4.2 Classification and Interpretation of Sources

The most critical stage in historical writing is source management. Without a structured approach to sources, even the most fascinating discoveries lose their meaning. I classify my materials into three primary categories — material, archival, and oral sources.

Material sources include excavated objects, architectural remains, pottery, coins, and tools. While analyzing them, I focus on aspects such as manufacturing technique, typology, and chronological context. Archival sources consist of inscriptions, copper plates, manuscripts, and ancient texts — each demanding linguistic and epigraphic expertise. Oral sources, on the other hand, come from folk traditions, local songs, and community legends, which preserve the “living memory” of history.

The real strength of research lies in the integration of these three types of evidence. For example, if an inscription mentions a ruler and the same figure appears in local oral traditions, the two become complementary — creating a bridge between evidence and memory. This harmony between tangible proof and cultural continuity gives depth and authenticity to historical writing.

4.3 Structuring and Presenting the Narrative

Once all the data and sources are organized, I move on to designing the structure of the article. I generally combine both chronological and thematic approaches — ensuring that while events unfold in order, the underlying ideas and interpretations flow naturally. In every paragraph, I strive for a balance between fact, analysis, and emotional resonance.

For me, writing is not just a technical task; it is a moral responsibility. When we give voice to the past, we must ensure that our words not only represent our perspective but also serve as a reliable source of knowledge for future readers. That is why I always include references, field photographs, and notes at the end of every paper. Transparency, I believe, is the essence of scientific writing.

4.4 Balancing Sensitivity and Scientific Rigor

The greatest challenge in archaeology and historical writing is maintaining a balance between sensitivity and scientific precision. If we focus only on facts, writing becomes dry; if we focus only on emotion, it loses credibility. In my experience, true history is that which stands firm on evidence yet touches the reader’s heart.

Whenever I complete a draft, I ask myself one simple question — “Does this piece bring the past to life?” If the answer is yes, then I know my work is complete. Because the purpose of historical writing is not merely to record what happened, but to explore why it happened — and what humanity learned from it. That, to me, is the true meaning of methodology and source management: a continuous effort to transform evidence into understanding, and understanding into wisdom.

5. Case Study: The Story of a Discovery

5.1 Introduction to the Project

This is the story of a discovery that not only gave my research a new direction but also allowed me to hear the living voice of history. In 2022, I was fortunate to join an excavation project in a small village named Khetri in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. Preliminary surveys had indicated that the site might contain the remains of an ancient settlement or a religious center. The hypothesis was supported by a few copper-plate references and local oral traditions that spoke of an old city once buried under the sands.

The objective of our project was clear — to study the stratigraphy of the site, document inscriptions and artifacts, and understand whether it was connected to any ancient trade routes or cultural networks. I was part of the field documentation team, responsible for identifying layers and maintaining photographic records. At that time, I had no idea that this field visit would become one of the most defining moments of my research journey.

5.2 The Moment of Discovery

On the third day of excavation, as we reached the third layer of soil, a faint metallic glimmer caught our eyes. Carefully brushing away the surrounding earth, we uncovered a copper-plate inscription with ancient characters etched upon it. Excitement rippled through the team — this was the first documented inscription from the site. The plate was immediately preserved and sent to the university laboratory for detailed analysis.

The inscription, written in Gupta Brahmi script, mentioned a ruler named Devadatta, who ordered the construction of a rest house and water reservoir in a settlement called Khetpura Nagar. What astonished us most was that there had been no previous historical record of any place by that name. It soon became evident that “Khetpura” could be the ancient name of what is now known as “Khetri.”

The inscription also referenced water management and public infrastructure — an extraordinary indicator of civic awareness and environmental planning during that period. For me, this was more than an archaeological find; it was evidence of how advanced and community-oriented the ancient Indian urban tradition truly was.

5.3 Analysis and Findings

Laboratory studies confirmed that the copper plate dated back to the 5th century CE. Its metallurgical composition, script style, and iconographic details were consistent with inscriptions from the late Gupta period. Comparative analysis led to the conclusion that this site may have served as an administrative or cultural hub during that era. This finding not only enhanced the historical importance of the region but also added a new dimension to the cultural identity of Shekhawati.

When we cross-referenced the inscription with local oral traditions, an interesting connection emerged. The village elders often spoke of an ancient pond called “Devsthan Talab,” believed to have been built by a ruler named Devadatta. The alignment between oral memory and material evidence was astonishing. It was a reminder that history survives not only in inscriptions and monuments but also in the living memory of communities.

5.4 Lessons from the Discovery

This case study taught me a profound lesson — that every discovery is not only physical but also philosophical. The copper plate was not just a piece of metal; it was a voice of time itself. When I held it for the first time, I felt as if the past was whispering its story directly into my hands.

The discovery also changed the way I approached my writing. I realized that the true purpose of historical writing is not simply to record findings, but to interpret their meaning — to understand their impact on society, culture, and human consciousness. Since then, I have tried to infuse this perspective into all my work: to treat every artifact as a storyteller, every inscription as a dialogue.

Ultimately, this discovery was more than the identification of an ancient site — it was a reflection of the larger tradition where archaeology and history complement one another. The words etched into that copper plate proved that civilization is not just a relic of the past, but a living spirit of continuity. That, to me, is the true essence of “The Story of a Discovery” — where evidence and experience unite to bring history back to life.

6. Conclusion: Lessons and Future Directions

Every journey leaves behind not only memories but lessons — and my journey through the realms of archaeology and historical writing has been no different. From studying ancient inscriptions to working under the blazing desert sun, each experience has deepened my understanding that history is not a closed chapter of time; it is an open conversation between humanity and its own existence. Archaeology has taught me patience, humility, and the art of listening — listening not with ears, but with the mind and heart, to what the earth wishes to reveal.

One of the most profound lessons I have learned is that the past is never truly “past.” It continues to shape our thoughts, identities, and decisions in ways we often overlook. Every artifact, every inscription, and every story we uncover holds within it the seeds of our collective consciousness. The deeper we dig, the more we understand ourselves — not just as individuals, but as a civilization that has continuously evolved through inquiry, creativity, and resilience.

As a researcher and writer, I now realize that the role of archaeology extends far beyond unearthing ruins or classifying artifacts. It is a discipline that connects evidence with imagination, science with sensitivity, and facts with philosophy. True history writing, therefore, is not about glorifying the past but about interpreting it with honesty and compassion. When evidence meets empathy, history becomes alive — it transforms from a record of events into a mirror reflecting the human journey.

Looking to the future, I believe the field of archaeology must embrace new technologies while preserving the essence of humanistic inquiry. Digital mapping, AI-based analysis, and satellite imaging are transforming how we document and interpret data. Yet, amidst all these innovations, the human touch — the ability to sense, to feel, to interpret context — remains irreplaceable. The future of archaeology lies in this fusion of scientific precision and cultural sensitivity.

For me personally, the journey does not end here. I see my work not only as a study of the past but as a contribution to the future — an effort to make history more accessible, meaningful, and emotionally engaging. I aspire to write in a way that encourages young scholars and readers to see archaeology not as a dry academic pursuit, but as a living exploration of who we are and where we come from. Because every discovery, no matter how small, reminds us that we are part of a story much larger than ourselves.

In the end, I have come to believe that archaeology and history are not about digging into the past — they are about digging into truth. The tools may change, the sites may differ, but the purpose remains the same: to understand humanity through time. And as long as we continue to seek that understanding with sincerity, the dialogue between the past and the present will never cease. That, perhaps, is the greatest lesson of all — that history is not something we leave behind; it is something we continue to build, one discovery at a time.