Introduction — My First Encounter with the Constitution

The First Glance: A Child's Curiosity

I grew up in a small town where the rhythm of life was shaped by school bells, local festivals, and neighborhood conversations. One of my earliest civic memories is hearing the opening lines of the Preamble — "We, the people of India..." — recited in assembly. At first, those words felt ceremonial, almost ornamental. Yet they stirred a quiet curiosity: what did these words mean for someone like me, living my daily life far from the halls of power?

As a child, the Constitution seemed like a distant text — an official document discussed by teachers and elders. Only later, through schooling and conversations, did I begin to sense that it was more than paper. The Preamble's promise of justice, liberty, equality and fraternity began to feel like an invitation to reflect on what citizenship could mean in everyday action.

A teacher's provocation

I still remember a schoolteacher asking our class: "Do these words change your life, or do you change their meaning through your actions?" Her question lingered in my mind. It pushed me to look beyond textbook definitions and ask how constitutional ideals could be translated into daily choices — how a pledge on paper might become a practice in neighborhoods, markets, and classrooms.

From Textbook to Thought: Learning in College

In college, when I enrolled in political science and history courses, the Constitution moved from being a quoted preface to a living subject of study. Lectures about the Preamble, fundamental rights, and directive principles opened up new ways of seeing law as a social instrument. I began to understand that the Constitution was less about abstract categories and more about designing institutions, duties, and expectations for collective life.

Reading original excerpts from constituent debates — the recorded voices of framers, reformers, and lesser-known delegates — made the drafting process feel less like an exercise of abstraction and more like a painstaking negotiation. Each phrase seemed chosen not just for legal precision but for moral weight.

A formative classroom incident

During one seminar, our professor challenged us to translate a few constitutional clauses into plain language. The exercise produced awkward, human sentences that suddenly made the clauses approachable. A fellow student asked, "If ordinary people read this, will they know their rights?" That moment convinced me that accessibility, not only legality, is central to constitutional efficacy.

Constitution as a Moral Map

Over time I came to see the Constitution as a moral map rather than a mere set of rules. It identifies core commitments a nation chooses to uphold. The principles outlined in the Preamble are not decorative lines — they are normative anchors that shape policy choices, judicial decisions, and civic expectations. For citizens, they offer a framework to evaluate governance and social practice.

This perspective influenced how I engaged with local civic life. When community disputes arose, I began to look for solutions informed by constitutional values: fairness, respect for dignity, equal access to services, and the protection of basic freedoms. The document became a lens through which to judge not just laws but the spirit of public life.

Bringing the Constitution to the Community

Motivated by this conviction, I worked on a small college project that aimed to simplify constitutional provisions for local citizens. We created a short leaflet that rendered key articles into simple language and distributed it at a village meeting. People asked practical questions — How does freedom of speech affect a tenant dispute? Can the law help women access local employment schemes? Their curiosity revealed the gap between constitutional text and day-to-day understanding.

Awakening to Rights and Duties

The more I read and listened, the more I realized that the Constitution pairs rights with duties. Rights empower citizens, but duties build the civic fabric that sustains those rights. In conversations with elders in my town, I observed that community norms and mutual obligations often mattered as much as formal rights. The Constitution, therefore, seemed to demand both legal awareness and ethical practice.

This combined lens — legal and moral — has guided my approach to local initiatives. Whether it was encouraging people to participate in a Gram Sabha or helping a neighbor file a simple petition, the Constitution's influence became visible in small actions that aggregated into broader social change.

Summary — The Beginning of a Constitutional Journey

The early stages of my encounter with the Constitution: from childhood impressions and classroom provocations to active community engagement. The central lesson is that the Constitution is meaningful only when its principles are understood and practiced by citizens. In the next part, we will explore how colonial laws and political movements laid the groundwork for the constitutional project that followed independence.

British Rule and the Foundations of the Constitution

Colonial Legal Framework: Seeds of a System

British presence in India was not only political and economic; it introduced a structured administrative and legal framework. The Regulating Act of 1773 began the process of regulating the East India Company's affairs. After the Revolt of 1857, the Government of India Act, 1858 placed governance under the Crown, reshaping administrative priorities and institutional arrangements.

Later reforms — notably the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms (1919) and the Government of India Act (1935) — gradually embedded constitutional ideas like provincial autonomy and federal structures. The 1935 Act, in particular, provided a model of center-state relations and legislative lists that influenced post-independence constitutional design.

A historical lesson

These statutes demonstrated that law can structure governance and public life. Yet they were largely top-down impositions, often disconnected from the aspirations of Indian society. That tension set the stage for a distinctly Indian constitutional project after independence.

Political Awakening: Movements, Organizations and Ideas

Alongside colonial laws, political consciousness grew. The founding of the Indian National Congress in 1885 catalyzed public debate and organization. Leaders such as Gandhi, Nehru, Subhas Bose, and many others mobilized popular support and articulated visions for self-rule and social justice. Mass movements — non-cooperation, civil disobedience, and the Quit India movement — translated constitutional ideas into popular practice.

Reports and proposals like the Nehru Report (1928) and the resistance to the Simon Commission signalled that Indian leaders were not merely passive recipients of British reforms; they were actively imagining alternative constitutional futures.

Personal reflection

Reading about these movements, I was struck by how ordinary citizens shaped constitutional outcomes. In my own town, elders recalled boycotts and local protests — small acts that contributed to a larger change. That grassroots energy was essential to building a constitutional consensus after independence.

Law, Courts and Public Life

The British established courts, legal procedures, and a strong rule-of-law tradition. High Courts and the later Supreme Court of India would inherit this institutional legacy. The legal profession and judicial review became critical components of constitutional governance.

However, the language and accessibility of law were often barriers for ordinary people. The challenge for Indian constitutional makers was to combine procedural rigor with social accessibility — ensuring laws protected citizens in practice, not only on paper.

A classroom anecdote

A college friend once observed that legal language can feel magical but distant. That remark resonated with me because constitution builders faced a similar dilemma: drafting precise legal rules while making the Constitution meaningful to millions across languages and regions.

Colonial Challenges and Indian Responses

British policies sometimes polarized communities and reinforced divisions. Economic inequalities, communal tensions, and the politics of divide-and-rule complicated the task of nation-building. Yet Indian leaders responded by articulating inclusive constitutional principles and proposing institutional mechanisms to manage diversity.

The 1935 Act’s emphasis on provincial autonomy and legislative lists provided structural ideas that Indian framers adapted, but they also sought to correct colonial exclusions by enshrining rights, social justice, and democratic participation.

Summary — Foundations Laid, Questions Raised

In this section we saw how colonial administrative and legal experiences provided building blocks for India's constitutional architecture, while political mobilization and popular movements supplied the normative force for a different future. The British left institutional legacies — courts, legislative frameworks, administrative practices — that were reshaped into a constitution aiming for inclusion, justice, and democratic governance.

The Constituent Assembly and the Constitution-making Process

Formation of the Constituent Assembly (1946)

The Constituent Assembly was the crucible in which modern India's constitutional identity was forged. Elected in 1946 under the Cabinet Mission Plan, the Assembly brought together a remarkable range of voices — lawyers, social reformers, political leaders, and representatives of diverse regions and communities. Although not a product of a direct adult franchise, it nevertheless reflected the varied aspirations of a country on the brink of unprecedented change.

The first time I read the list of Assembly members, I felt a deep sense of awe. Names like Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, and Rajendra Prasad stood out, but so did lesser-known figures whose local knowledge and moral courage shaped vital debates. It was this mixture of national vision and local insight that, in my view, gave the Assembly its unique strength.

Key committees and working methods

The Assembly worked through committees — among them the Drafting Committee, the Union Powers Committee, and the Advisory Committee. The Drafting Committee, chaired by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, played an especially pivotal role in translating philosophical ideals into workable legal text. The methodical, almost craftsman-like approach of these committees contrasted with the urgency of the times, but that balance between careful drafting and urgent action defined the process.

Major debates and difficult choices

The Constituent Assembly's sessions were not mere formalities; they were arenas of intense debate. Issues such as the nature of the federal structure, the balance between fundamental rights and directive principles, the role of religion in public life, and the language policy provoked passionate arguments. The trauma of Partition loomed large and influenced many of these debates, making the task of forging unity out of diversity both urgent and delicate.

Personally, when I read the recorded debates years later, I was struck by the dignity and patience with which leaders engaged one another. Even in disagreement, there was a persistent commitment to dialogue. This taught me a valuable lesson: constitution-making is as much about negotiating relationships and trust as about drafting clauses.

The role of minority rights and social justice

Social justice emerged as a central preoccupation. The Assembly confronted questions about caste disabilities, untouchability, and the socio-economic backwardness of many communities. Dr. Ambedkar's interventions, rooted in both moral conviction and legal scholarship, steered the Assembly towards provisions that sought to protect the marginalized and promote equality. The inclusion of fundamental rights and later the framing of reservation policies were direct outcomes of such sustained moral engagement.

Drafting the text: from ideals to clauses

Transforming lofty ideals into precise legal provisions required exceptional care. The Drafting Committee studied constitutions from around the world — borrowing elements from the Government of India Act, the British parliamentary model, the American Bill of Rights, and constitutions of several other countries. Yet the aim was not imitation; it was adaptation. The text had to resonate with India's social realities and administrative needs.

I remember participating in a seminar where a senior teacher explained how every phrase in the final draft had been weighed for its long-term implications. That insight stayed with me: words in a constitution do not merely regulate; they shape future expectations and institutional practices.

Public engagement and communication

While much of the drafting was a deliberative, inside-the-room process, public engagement mattered too. Debates and summaries were reported in newspapers; activists and community leaders brought local concerns to the attention of Assembly members. In later years, I took inspiration from that practice and tried to communicate constitutional ideas to students and local groups in plain language. Making the Constitution accessible was, for me, a continuation of the Assembly's democratic spirit.

Adoption, signatures, and the emotional moment

On 26th November 1949, the Assembly adopted the final text of the Constitution. The ceremonial signing by its members was more than a constitutional formality — it was an emotional affirmation of collective resolve. Rajendra Prasad, as President of the Assembly, presided over the occasion; K.M. Munshi read the Preamble aloud. The sense of a new political birth was palpable.

Reading firsthand accounts of that day, I often imagined the mixed feelings in the room: relief at the conclusion of a long labor, sorrow over partition's scars, and hope for a shared future. That complex emotional landscape reminds us that constitutions are born out of both reason and feeling.

summary — craft, contest, and consensus

The Constituent Assembly combined meticulous drafting with spirited debates to produce a text that sought to balance ideals and practical governance. The process was not without tension, but the commitment to deliberation, protection of rights, and inclusion of marginalized voices marked it as a foundational democratic exercise. In the next section, we will reflect on the role of key individuals — especially Dr. B.R. Ambedkar — and the philosophical underpinnings that shaped the Constitution's character.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar — The Architect of the Constitution

From Struggle to Resolve: Ambedkar's Life

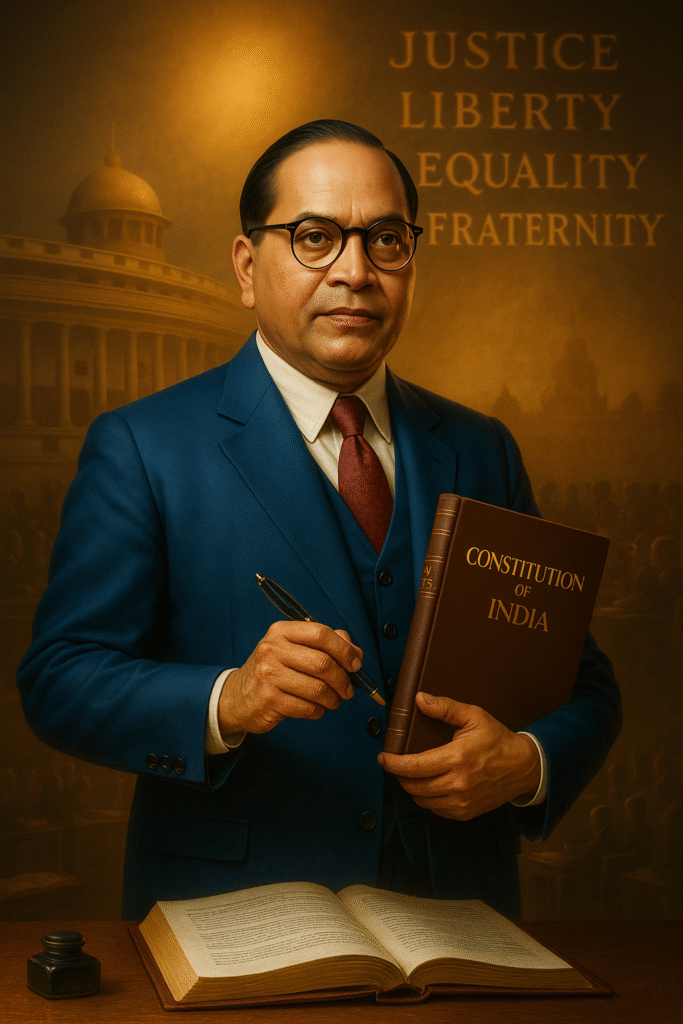

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar's life was not merely a personal journey; it was a social revolution in motion. Born into a society riddled with exclusion, he transformed adversity into academic excellence and public service. His education abroad and his perseverance back home demonstrated how rigorous thought and relentless effort can challenge entrenched inequalities.

When I first read Ambedkar's biography, I was struck by the way his individual struggle became a collective aspiration. He did not limit himself to critique; he fashioned legal and institutional tools to dismantle social barriers. For me, Ambedkar embodies the conviction that law can be an instrument of social transformation.

A formative encounter

A college mentor once remarked, "Ambedkar did not simply draft laws; he converted the language of law into a weapon for social justice." That insight shaped my understanding of constitutionalism as inherently moral as well as technical.

Shaping the Text: From Principles to Provisions

As chair of the Drafting Committee, Ambedkar played a pivotal role in converting political ideals into precise constitutional clauses. He championed provisions that aimed at abolishing untouchability, guaranteeing fundamental rights, and fostering equality of opportunity. His priority was clear: the Constitution must protect the most vulnerable.

Many clauses that seek to correct historical injustices and ensure affirmative action bear his intellectual imprint. Ambedkar insisted that constitutional language should not only enshrine rights but also pave the path for substantive social change.

Technical mastery and moral conviction

What made Ambedkar extraordinary was his ability to combine rigorous legal scholarship with deep moral purpose. He extensively studied other constitutions and legal traditions, selecting and adapting elements appropriate to India's social realities. This combination of comparative insight and contextual sensitivity was central to his craft.

Speech and Philosophy: Justice, Liberty, and Equality

Ambedkar's speeches reveal a persistent commitment to social justice. He repeatedly emphasized that rights without access and opportunities are hollow. His rhetoric was grounded in legal reasoning, but it was always animated by human empathy and a demand for dignity.

Reading his recorded interventions in the Assembly, I felt the moral urgency in his words. He appealed not merely to legal logic but to the nation's conscience — a quality that continues to anchor constitutional debates today.

Precision in language

Ambedkar's drafting style was marked by precision and clarity. He weighed words carefully, aware that constitutional phrasing would shape institutions and expectations for generations. That attention to linguistic detail helped the Constitution endure and remain effective in practice.

Personal Impact: What Ambedkar Means to Me

To me, Ambedkar is not only a historical hero but an intellectual companion. His insistence on equal dignity and structural remedies informs my reflections whenever constitutional questions arise. I have organized discussions in my community around his ideas, and each conversation reaffirms his continuing relevance.

His life teaches that legal reform must be accompanied by social mobilization, education, and persistent advocacy. Ambedkar's blend of scholarship and activism remains a model for those who seek justice through institutional change.

An enduring imprint

If one were to name the moral spine of the Indian Constitution, Ambedkar's influence would stand at its center. He shaped the document not merely as a charter of governance but as a manifesto for social transformation. His legacy persists in constitutional principles, judicial reasoning, and public movements for equality.

Summary — Thinker, Craftsperson, and Guide

This section traced how Dr. B.R. Ambedkar combined personal struggle, academic rigor, and moral resolve to shape India's constitutional framework. He was a thinker who translated ideals into institutional design, a craftsperson who honed legal text with care, and a guide whose vision continues to inform India's pursuit of justice. In the next part, we will examine the formal enactment of the Constitution and the significance of January 26, 1950 — the day the document came into force.

Adoption of the Constitution — The Birth of a New India

The Historic Day of Adoption — 26 November 1949

The Constituent Assembly adopted the final text of the Constitution on 26 November 1949. After years of deliberation, drafting, and debate, the adoption marked a formal pledge by representatives of India to a set of principles that would guide the nation. The act of adoption was not merely the passing of a document; it was a collective vow to uphold justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

The atmosphere in the Assembly

Contemporary accounts describe the Assembly on that day as tense and solemn, a room full of relief and resolve. The shadow of Partition still lingered, but for the members present, adoption signified a chance for reconstruction and collective renewal. Leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, and many others spoke with a mix of gravity and hope, acknowledging the enormous task ahead.

The Preamble Read Aloud — Symbolism and Substance

The Preamble was read in the Assembly as the summarizing statement of the Constitution's purpose — “We, the people of India...” These opening words enshrined the ideals the nation sought to realize: justice, liberty, equality and fraternity. The Preamble served as both a moral compass and a symbolic assertion of a new democratic identity for India.

What the Preamble meant to ordinary citizens

For many, the Preamble distilled complex legal language into a set of shared values. It offered a vision that citizens could relate to — a promise that governance would aim to secure rights and opportunities for all. For me, reading the Preamble for the first time felt like encountering a civic creed that demanded not only rights but also responsibilities.

26 January 1950 — The Constitution Comes into Force

The Constitution became effective on 26 January 1950, a date chosen to honor the declaration of Purna Swaraj (complete independence) in 1930. January 26 thus became Republic Day — the day India began to function under its own supreme law. Institutions of governance — legislature, executive and judiciary — assumed their constitutional roles with new legitimacy and structure.

Practical changes and institutional beginnings

With enactment, citizens received formal guarantees of fundamental rights, and the framework for governance shifted to constitutional processes. Administrative machinery had to be reoriented, courts adapted to interpret new rights, and legislators began the work of making laws consistent with constitutional principles. These were not instantaneous fixes; they required training, legal reform, and public education.

Early challenges and the work of implementation

Adoption and enactment were the beginning — implementation posed profound challenges. The immediate post-adoption years confronted India with refugee resettlement, economic rebuilding, and the task of integrating princely states. Translating constitutional commitments into social and economic reality required state capacity, public awareness, and sustained political will.

A local perspective — democracy taking root

At a local level, I observed gradual changes: village councils becoming more structured, schools and clinics opening under new programs, and ordinary people learning to frame grievances in rights-language. These small, incremental shifts illustrated how a constitutional order grows from the grassroots upward, not only from statutes downward.

The cultural and moral impact of adoption

The Constitution changed more than law — it challenged social norms. Provisions against untouchability, recognition of women's rights, and emphasis on equality and education began to reshape aspirations. The adoption signaled a moral reorientation; law became a tool for social change, not merely a mechanism for order.

My takeaway: adoption as a long-term commitment

The most enduring lesson from adoption is that constitutions require guardianship. A written charter produces its fruits only when institutions, citizens, and civil society continuously nurture its promises. Adoption is the seed; implementation, interpretation, and civic engagement are the ongoing cultivation.

Summary — Promise, Promise-keeping, and Practice

The emotional and institutional significance of adopting and enacting the Constitution — moments of national promise that launched a long endeavor of democratic practice. The adoption (26 November 1949) and coming into force (26 January 1950) remain founding milestones that continue to guide India's constitutional journey.

In the next section we will examine the Constitution's key features — federal structure, fundamental rights, directive principles, and the parliamentary system — and reflect on how these features were designed to meet India's unique needs.

Key Features of the Constitution

Size and Uniqueness of the Indian Constitution

The Indian Constitution is often described as one of the longest written constitutions in the world. Its breadth — reflected in numerous Articles, Parts and Schedules — responds to India's vast diversity and complex social-economic challenges. The document is not only a framework for governance but also an expression of national aspirations.

A personal perspective

When I first studied the structure of the Constitution, I was struck by its systematic design. It felt like an engineered construct that also carried the warmth of social sensitivity — a balance that makes it remarkable.

Federal Structure and Centre-State Relations

The Constitution adopts a quasi-federal model with a strong unitary bias. Powers are distributed between the Union and the States through three lists — Union, State and Concurrent — which define legislative competence. The design seeks to balance regional autonomy with national unity.

Practical insight

From my experience, federalism becomes effective when the Centre and States work with mutual respect and continuous dialogue. Legal provisions alone cannot sustain cooperative federalism without political will and administrative coordination.

Parliamentary System and Responsible Government

India follows a parliamentary form of government where the executive is accountable to the legislature. The Prime Minister and Council of Ministers must retain the confidence of the elected House, ensuring that the government remains answerable to representatives of the people.

The democratic spirit

The parliamentary system underscores the importance of debate, dissent and accountability. It taught me how representative institutions can channel public aspirations into policies and laws.

Fundamental Rights

The Constitution guarantees fundamental rights to citizens — including equality before law, freedom of speech and expression, protection from exploitation, religious freedom, and access to legal remedies. These rights function as safeguards against arbitrary state action.

Judicial support

In my interactions and teaching, I found it crucial to emphasize that fundamental rights are meaningful only when citizens are aware of them and courts are accessible to enforce them.

Directive Principles of State Policy

Directive Principles guide the State toward establishing a welfare-oriented polity. Though not justiciable in courts, these principles influence legislation and policy on education, public health, social welfare and economic justice.

Guidance versus enforceability

While fundamental rights are enforceable, Directive Principles provide moral and policy direction. Their real impact emerges when governments translate these guidelines into concrete programs.

Secularism and Social Inclusion

The Constitution enshrines secularism as a foundational principle — the State does not favor or endorse any religion and aims to treat all faiths impartially. At the same time, the document provides measures for social inclusion, such as affirmative action for historically disadvantaged groups.

Signs of social change

My observations in communities show that secularism is more than legal neutrality; it requires active respect for diversity and equal opportunity in daily life.

Independent Judiciary and Judicial Review

The judiciary, headed by the Supreme Court, serves as the guardian of the Constitution. Judicial review allows courts to examine the constitutionality of laws and governmental actions, thereby protecting fundamental rights and resolving federal disputes.

Trust in justice

Where judicial remedies function and communities trust courts, constitutional governance deepens. Local experiences of fair adjudication strengthen public confidence in constitutional values.

Single Citizenship and National Integration

The Constitution provides for single citizenship across the Republic, reinforcing legal unity and uniform rights for all citizens regardless of state boundaries.

Unity in diversity

Single citizenship helps maintain a shared political identity amidst linguistic and cultural differences, a balance I believe is central to India's unity.

Emergency Provisions

The Constitution contains emergency provisions that allow the Union to assume special powers in times of war, external aggression, or breakdown of constitutional machinery in a state. These provisions are designed to protect the nation but require safeguards against misuse.

A call for vigilance

In my view, emergency powers should be invoked only as a last resort and with robust accountability to prevent erosion of democratic rights.

Amendment Procedure

The Constitution provides mechanisms for amendment, enabling necessary change over time. The amendment process balances flexibility with stability — some provisions can be amended by simple parliamentary majorities, while others require special procedures or ratification by states.

Flexibility and continuity

Amendment mechanisms allow adaptation to new realities while preserving core constitutional values. The doctrine of the 'basic structure' later articulated by the judiciary further protects essential features from being obliterated.

Schedules, Language Policy and Administrative Design

Numerous Schedules and language-related provisions help manage administrative complexity and respect cultural plurality. These structural details enable practical governance across diverse regions.

The importance of local context

My experience shows that constitutional principles take root when implemented in ways that respect local languages, traditions, and administrative realities.

Summary — Principle and Practice in Balance

This section has outlined how the Indian Constitution integrates federalism, parliamentary democracy, fundamental rights, directive principles, and an independent judiciary into a coherent whole. Its true strength appears when these features move from paper to practice — when laws shape education, justice, and social inclusion in everyday life.

Amendments and the Evolution of the Constitution

Why Amend? The Need for Change

A living constitution must balance stability with adaptability. Societies change — political priorities shift, technologies emerge, and social expectations evolve. Amendments allow a constitution to respond to new realities while preserving its foundational principles. In India, Parliament has used the amendment power to refine governance, enhance social justice, and address administrative needs.

A personal note

In my view, amendments are most valuable when they are grounded in broad public interest and respect the core values of constitutional democracy. Changes driven purely by short-term political gains risk weakening the institutional fabric that the Constitution seeks to protect.

Milestone Amendments and Their Effects

Throughout its history, the Constitution has been amended many times. Some amendments have been transformative, reshaping institutional balances or expanding rights; others were corrective responses to political circumstances. Notable examples include the 42nd Amendment, the 44th Amendment, and the 73rd & 74th Amendments that formalized local self-government.

The 42nd Amendment (1976)

Enacted during the Emergency, the 42nd Amendment is one of the most controversial changes in constitutional history. It expanded Parliament's powers, altered various provisions, and attempted to strengthen the role of the state in social and economic matters. Critics argued that it disturbed the balance between branches of government and curtailed judicial review.

The 44th Amendment (1978)

The 44th Amendment rolled back several provisions of the 42nd Amendment and sought to restore civil liberties and safeguards against arbitrary executive power. It reaffirmed the protection of fundamental rights and introduced safeguards around proclamations of Emergency.

The 73rd & 74th Amendments (1992)

These amendments gave constitutional status to Panchayati Raj institutions and urban local bodies, respectively. By decentralizing governance, they aimed to enhance grassroots democracy and local accountability — reforms that have had tangible impacts in many regions.

Judiciary and the 'Basic Structure' Doctrine

While the Constitution allows amendments, the judiciary has acted as a guardian of its essential character. In the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), the Supreme Court advanced the doctrine of the 'basic structure', holding that Parliament could not alter the Constitution's fundamental framework. This doctrine preserves certain core features — such as democracy, rule of law, and fundamental rights — from being abrogated through amendments.

The balance of power

The 'basic structure' doctrine underscores the tension and balance between legislative supremacy and constitutional continuity. It reflects the judiciary's role in protecting constitutional identity while allowing democratic institutions to enact reforms.

Socio-Political Developments and Constitutional Adaptation

Over decades, economic liberalization, social movements, and technological change have posed new questions for constitutional governance. Issues such as environmental protection, information rights, privacy, and digital governance required either legislative action, executive policy, judicial interpretation, or constitutional amendment to align constitutional norms with contemporary realities.

Examples of evolving constitutional practice

The emergence of the Right to Information, the expansion of environmental jurisprudence, and judicial recognition of privacy as a fundamental right demonstrate how courts and institutions interpret constitutional norms to meet new challenges. These developments illustrate constitutional dynamism beyond formal amendments.

Risks and Responsibilities in Amending the Constitution

Amendments can strengthen the constitutional order, but they can also create risks if used without deliberation. Responsible amendment practices include public debate, legislative scrutiny, and respect for judicial review. Broad consensus and transparency help maintain legitimacy and prevent erosions of fundamental rights or institutional checks.

A civic perspective

From my experience engaging with students and local communities, I have found that informed public participation is vital. When citizens understand constitutional stakes, amendments become opportunities for deepening democracy rather than instruments of short-term politics.

Looking Forward: Continuity and Change

The story of constitutional amendments in India is a testament to both continuity and change. The document has evolved through a combination of parliamentary action, judicial interpretation, and civic advocacy. Going forward, preserving the Constitution's core values while enabling thoughtful adaptation will remain the central constitutional challenge.

Summary — Wisdom in Change

The Constitution adapts: through amendments, judicial safeguards, and evolving practices. The key lesson is prudence — change is necessary, but it must be pursued with respect for the constitutional ethos that sustains democratic life.

Relevance of the Constitution in Modern India

Constitutional Questions in the Digital Age

The rapid digitization of public life has raised fresh constitutional questions. Issues of privacy, data protection, digital expression and algorithmic governance now intersect with fundamental rights. Courts and lawmakers are required to interpret age-old principles in light of new technologies — ensuring that freedom of speech, equality and liberty retain real meaning online as well as offline.

Practical concerns

From e-governance platforms to mobile financial services, access to digital tools has expanded citizen participation. Yet, protecting personal data and preventing surveillance misuse are central constitutional concerns that require robust law and civic awareness.

Environmental Justice and Constitutional Duty

Environmental challenges — air and water pollution, deforestation and climate change — have become constitutional questions about the right to life and future generations' welfare. Courts have increasingly read environmental protection into fundamental duties and directive principles, making ecological stewardship part of constitutional governance.

Local impact

When environmental norms are translated into local policy, communities experience tangible benefits: cleaner water sources, improved health outcomes, and sustainable livelihoods. The Constitution's guidance supports these long-term public goods.

Transparency, Accountability and the Right to Information

Instruments like the Right to Information (RTI) exemplify how constitutional values of accountability and participatory democracy can be operationalized. RTI empowers citizens to seek information, hold officials to account, and strengthen public faith in institutions.

Civic practice

The effectiveness of transparency measures depends on active civic use and responsive institutions. In places where citizens regularly use information tools, governance tends to be more responsive and corruption risks diminish.

Judicial Interpretation and Dynamic Constitutionalism

The judiciary plays a pivotal role in keeping the Constitution relevant. Through interpretation, courts have extended constitutional protections to areas like privacy, environmental rights, and digital speech. This dynamic jurisprudence helps constitutional norms adapt without frequent formal amendment.

Maintaining balance

Judicial intervention must be balanced with respect for legislative policy-making. Healthy constitutional practice involves constructive interaction among courts, legislatures and the executive.

Youth, Education and Constitutional Awareness

The Constitution's future depends on civic education and youth engagement. Schools, universities and civil society that teach constitutional values — rights, duties, pluralism and critical thinking — empower the next generation to uphold democratic norms.

Emerging leadership

Young people, digitally connected and socially aware, can renew constitutional culture by translating ideals into action: community service, public interest litigation, and informed political participation.

Social Media, Free Expression and Misinformation

Social media platforms amplify voices but also spread misinformation and polarize communities. Constitutional protections for speech must be balanced with safeguards for public order, dignity and truth. Law, platform governance and media literacy together shape a healthy public sphere.

A civic responsibility

Citizens and educators alike have a role in promoting media literacy so constitutional freedoms do not become tools for harm or division.

Economic Change, Labour Rights and Social Security

Economic reforms, gig work and globalization pose questions about workers' rights, social security and equal opportunity. Directive Principles and constitutional commitments to social welfare provide a normative framework for policies that protect vulnerable workers and foster inclusive growth.

Policy implications

Constitutional values guide policies on minimum standards, employment protection and social safety nets — ensuring economic progress is compatible with dignity and fairness.

Public Health, Pandemics and Constitutional Governance

Recent health crises have tested state capacities and constitutional balances between public safety and individual freedoms. Emergency responses must be proportionate, time-bound and legally accountable to preserve constitutional values even under stress.

Resilience and law

Strengthening public health infrastructure and embedding legal safeguards for emergencies are constitutional priorities to protect life and liberty.

Federal Relations and Cooperative Governance

Contemporary challenges — disaster response, health, environment and economic coordination — underscore the need for cooperative federalism. Constitutional design encourages both unity and regional autonomy; practical cooperation among centre and states is essential to implement large-scale reforms.

Collaborative solutions

Strong intergovernmental institutions and dialogue sustain the federal compact and translate constitutional commitments into effective public programs.

Summary — Living Principles, Lived Practice

The Constitution remains relevant in modern India because it supplies principles that guide law and policy even as circumstances change. From digital rights to environmental justice, from labour protection to public health, constitutional values offer a durable framework. Yet relevance depends on active institutions, vigilant courts, responsive governments and engaged citizens who continually translate text into practice.

Conclusion — My Lessons and Inspirations

The Constitution: A Commitment Beyond Words

For me, the Constitution is more than a legal text; it is a commitment that every citizen must internalize. Throughout this series, I have come to see that the words of the Preamble — justice, liberty, equality and fraternity — become transformative only when they guide everyday decisions. The document’s value multiplies when its principles are reflected in public life.

Lessons from personal experience

Local experiences taught me that constitutional change and justice reach their deepest roots when they become part of school lessons, village meetings and family conversations. Small acts — using the Right to Information in a local grievance, running literacy drives, or organizing discussions against social discrimination — are practical ways to live the Constitution.

Citizenship: Rights Coupled with Duties

The Constitution grants rights but also reminds us of duties. A vibrant democracy requires active citizens — voting thoughtfully, raising community concerns, and respecting others’ rights. Rights without duty are fragile; civic responsibility is essential to uphold democratic life.

Inclusion and sensitivity

The ideas of Ambedkar and other framers taught me that social inclusion does not happen by words alone. It requires deliberate policies, education, and empathetic social behavior. Ensuring dignity and equal opportunity demands sustained effort across generations.

Keeping the Constitution Alive: Institutions and People

The Constitution remains alive when the judiciary, legislature and executive honor their roles while maintaining checks and balances — and when citizens demand accountability. Judicial interpretation, effective policy implementation and civic participation together translate constitutional ideals into reality.

A message for the future

The younger generation, through education and technology, can renew constitutional culture. But this requires practical civic education, critical thinking and tolerance. Democracy is more than casting a vote; it is a continuous social practice.

Final Inspirational Note

My humble plea is simple: let us embody the Preamble. When we not only read but understand and practice "We, the people of India," the nation truly advances. The Constitution points the way; preserving it, practicing it, and handing it on to coming generations is our collective duty.

Summary — Learn, Live, and Carry Forward

In this concluding section I sought to weave history, process and personal reflection into a living portrait of the Constitution. My core message is straightforward: read the Constitution, understand it, and strive to live by its principles. That is the greatest tribute we can offer to those who crafted this remarkable document.